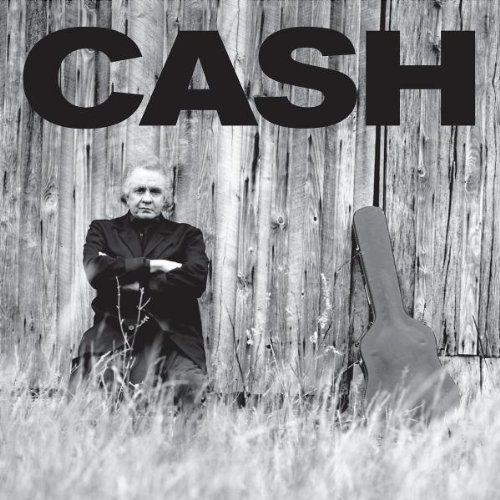

If there’s a voice that spans the imagined gulf between country music and rock, it belongs to Johnny Cash. Not because he started out at Sun Records, roomed with Waylon, married June Carter, booked rock stars on his variety show, crossed between radio formats like a mountain goat — none of that.

Because of this: Johnny Cash’s voice is as pure and unadorned and enduring a thing as American music can call its own.

That deep, resonant instrument has been a constant part of American aural culture since the ’50s, from rockabilly to country to gospel to Shel Silverstein’s “A Boy Named Sue” to whatever you want to label the Highwaymen — and never mind the Columbia foolishness of not renewing his contract a few years back. Who else has remained so vital for so long?

Oddly enough, that space between what is country and what was rock had both narrowed and widened when Cash’s American Recordings arrived in 1994. Country had gone pop, and showed (for the first time) little use for the past Cash and his generation represent. Rock had run away from words and music and into sound, addressing the sense of being particularly disaffected yet singularly unable to voice more than that least transcendent of emotions. (Ah, but it felt good, for awhile.)

And so Rick Rubin, who has produced such rock bands as Slayer, The Cult, and the Beastie Boys for godsakes, had the sense to sign Cash and encourage a stunning acoustic album from him. And it sold. Rock kids remembered the icon (guess how many alternative stars had Johnny Cash albums in their bedrooms?), and older country fans were happy to have something that was still theirs in the marketplace.

Two years later, Rubin has paired Cash up with Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers. In some circles that’s a headline, but (perhaps to their credit) the Heartbreakers are pretty irrelevant to the success or failure of Unchained. They’re a competent backing band who neither add to nor subtract from the songs; that is, it only matters who the supporting players are if you’ve been told. And my only objection is that they seem unable or unwilling to push Cash, which he seems to like and expect of younger musicians.

The other headline is that Cash covers such songs as Beck’s “Rowboat”, Soundgarden’s “Rusty Cage”, and Petty’s “Southern Accents”. This should not come as a surprise (though apparently Cash took some persuading before trying “Rusty Cage”), for a quick pass through the man’s indispensable box set — The Essential Johnny Cash 19551983 (Columbia/Legacy) — reveals songs credited to Bob Dylan, Mssrs. Jagger & Richards, Nick Lowe, and Bruce Springsteen.

A song is a song, folks.

All right, all right, inquiring minds want to know and all that: “Rowboat”, which opens Unchained, makes a strong case that the hype around Beck might have some substance. It’s a perfect Johnny Cash song: simple, loping, open enough for the emotion to be implied instead of insisted upon. And Cash nails it as surely as he’s hammered anything in his career. “Rusty Cage”, transposed away from Chris Cornell’s penchant for operatic heights, very nearly comes off, and probably will in concert. “Southern Accents” is a pretty trite affair, but given Cash’s voice-of-god intonation, it’s at least honorable.

But taken as a whole, Unchained is a curious set of songs. American Recordings played very much as a suite, but not this one. Ice newsletter reports that Cash recorded 30 tracks, intending at one point to release a double album. 14 cuts surface here (we’re deprived, Ice reports, of Neil Young’s “Pocahontas” and Robert Palmer’s “Addicted to Love”), including a pretty fair remake of Cash’s own 1960 “Mean Eyed Cat”. But — and maybe this has only to do with what country radio in Seattle played in the early ’80s — why on earth dust off Hank Snow’s 1962 novelty namedropper “I’ve Been Everywhere,” or Roy Clark’s 1970 hit “I Never Picked Cotton”?

Cash, who seems as comfortable with his religion as he does with his sobriety and his fame, has become a superb gospel singer, and so in his hands the Louvin Brothers’ “Kneeling Drunkard’s Plea” is not a maudlin, moldy classic, but a touching tale of rebirth and bad timing. “Meet Me In Heaven”, a new Cash composition, manifests a wonderfully plainspoken, honest spirituality that seems largely absent from organized religion these days.

However, that same voice of aged wisdom seems out of place with “I Never Picked Cotton”. Mind you, it’s a great song, as complicated a portrait of rural America as Roy Clark or anyone else ever penned. Picture a moral world — and at this point Cash sings from no other point of view — in which the crippling poverty of farm labor can be redeemed by a life of crime, and the closing lines are, “They’ll take me in the morning / To the gallows just outside / And in the time I’ve got / There isn’t a hell of a lot / I can look back on in pride / But I never picked cotton.” That’s as bleak and savage an indictment of the American dream as anything rock has managed. That Clark had a hit with it in 1970 — at the height of the Vietnam War — is almost surreal. Hearing it from Cash’s lips in 1996 is flat disorienting.

Country albums are traditionally much like Unchained, with bits and pieces for everybody, just collections of songs, some of which hope to be hits. Rock musicians, from the Beatles forward, have sometimes conceived their albums to be more, to be coherent artistic statements. (Which is why Willie’s Red Headed Stranger was such a landmark.) New country, having become the new pop music of the early-middle-class, still hasn’t learned that trick, in part because country (unlike rock) so relies on absent songwriters. American Recordings offered so much coherence, such a plain and unswerving vision, that Unchained simply can’t help but be a letdown.