Leonard Cohen’s Memento Mori

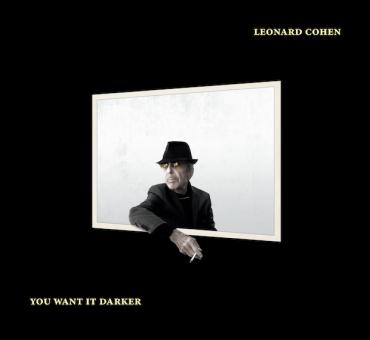

Over the course of almost fifty years, Leonard Cohen has plumbed the beauty and perils of love, the fragility of existence, and the highs and lows of human history. With 2012’s Old Ideas and 2014’s Popular Problems, Cohen steered in a more noticeably confessional direction, addressing the hardships of ageing and the persistent illusions associated with personality and conditioning, particularly in the Western world. His latest and fourteenth album, You Want It Darker, however, is his most revealing and aesthetically unified release to date—vocally, lyrically, and musically compelling from the first track to the last.

The album opens with the title song, the aptly mixed and balanced choral arrangement and rhythmic pulse setting the tone of the project. Cohen’s baritone is as resonant, sonorous, and mysterious as ever. With the first chorus—“Hineni Hineni / I’m ready, my Lord”—Cohen echoes Abraham of Genesis as well as Christ on the cross, exceeding his most memorable performances, including such stellar moments as “I’m Your Man,” “Hallelujah,” “Tower of Song,” and “The Future.” The arrangement is impeccable (kudos to Cohen’s son Adam for his production skills), delicate passages seguing into complex soundscapes, textured instrumentation highlighting Cohen’s arresting disclosures. The biblical references are familiar ground for Cohen; however, with this track (and album) Cohen more adeptly than ever personalizes the metaphors of Judeo-Christianity and the principles of Zen Buddhism. At eighty-two, Cohen is apparently facing death—bodily death and egoic death—documenting his experience with a depth, acumen, and presence unparalleled in the popular canon.

With “Treaty,” Cohen again employs religious references and imagery; however, the persona of the piece is crafted ahistorically. The singer is possibly Satan addressing God, wishing for reconciliation. Then again, the singer may indeed be human, attempting to make peace with his failures and the perceived indifference of his creator. The ambiguity is undoubtedly intentional and, in any case, effective. Cohen moans, “We sold ourselves for love but now we’re free.” In a particularly intriguing couplet, Cohen laments, “I’m so sorry for the ghost I made you be / Only one of us was real – and that was me.” The Old and New Testaments remain Cohen’s primary sources, even as he mines them to consider metaphysical insights, autobiographical connections, and overlaps with Eastern teachings regarding suffering and enlightenment.

With the fourth track, Cohen vividly addresses the process of dying: “I’m leaving the table / I’m out of the game.” And in a particularly memorable passage:

I don’t need a lover

The wretched beast is tame

I don’t need a lover

So blow out the flame

Lennon’s reinvention of himself post-Beatles is a probable comparison; however, while Lennon’s solo work and collaborations with Yoko Ono enabled Lennon to express newfound enthusiasm around “no longer riding on the merry-go-round,” Cohen is documenting his consummate exit from worldly pursuits. While Lennon was rearranging his priorities, Cohen is embracing the obsolescence of self. An additional comparison might be Dylan’s Time Out of Mind; however, while Dylan rarely transcends a signature cynicism, even on such haunting tracks as “Standing in the Doorway,” “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven,” and “Not Dark Yet,” Cohen expresses his disillusionment and despondence directly and vulnerably, uninsulated by the buffers of bitterness and exceptionalism. That’s not to say that Cohen, as a singer and songwriter, doesn’t utilize persona; persona may well be an inevitable component of artistic expression, indeed any expression; that said, one of the chief missions of You Want It Darker is the investigation and relinquishment of persona, even if the mission isn’t fully realized, and even if, ironically, persona is used to further the process. Cohen might appreciate the observation that an attempt to shed persona can itself become a means by which persona is reinforced or revised; that when it comes to dying, the ego may be the last thing to perish.

Zac Rae’s flamenco-style guitar and Athena Andreadis’s supporting vocals on “Traveling Light” make for a poignant intro. The subtle piano touches are engaging; also salient is the balanced mix between David Davidson’s sweeping violin and the programmed percussion by Patrick Leonard and Michael Chaves. The movements between sparse and more complex passages remind me of the scene in Zorba the Greek when Zorba (Anthony Quinn) and Basil (Alan Bates) dance together in the sand (expressing both ecstasy and sorrow), the Mediterranean lapping in the background.

“It Seemed the Better Way” is the apex of the album and represents a new zenith for Cohen in terms of songwriting craft and delivery (the only comparison I can readily think of is Nina Simone’s extraordinary version of “Strange Fruit,” recorded in 1965). From the opening hum of the supporting vocals to the inclusion of an etheric violin part to Cohen’s opening lyric, the piece is utterly transportive. The singer’s reference to “lift[ing] a glass of blood” suggests that he might be an ancient vampire reflecting on two millennia of human distress; how Christ’s message “sounded like the truth,” “seemed a better way,” though “it’s not the truth today” (if Jim Jarmusch ever decides to film a sequel to Only Lovers Left Alive, he should use this song during the closing credits).

On “Steer Your Way,” Cohen frequently sounds as if he’s on the verge of tears, vetting concepts, ideals, and conclusions that he “believed in yesterday” but that have ultimately proved illusionary, egoic content exposed as a palimpsest of constructs, peeled away as the end of life approaches. The album closes with a mostly instrumental track (alternately funereal and auroral), Cohen’s reiteration of the key line from “Treaty” delivered in the final minute: “I wish there was a treaty / between your love and mine.”

Rating works of art is often a mistake; there’s always the risk of reducing what is by nature multifaceted and elusive to a singular and capitalistic bottom line, rendering it a one-dimensional commodity. At times, however, it’s descriptively useful. Cohen has released several benchmark albums during his career, including his debut (1967), I’m Your Man (1988), and Ten New Songs (2001). With You Want It Darker, however, he’s forged his magnum opus. If this album does indeed prove to be his last, it’s one hell of a swansong. 5 stars.