Lost Radio Recordings Give Picture of Hank Williams in Final Years

A few weeks before his death in 1953, Hank Williams was having a problem getting through a matinee performance in San Diego due to an over-serving of what iconic country comedian Minnie Pearl referred to in her account of the incident as “help from outside causes.” Tasked by the promoter with the responsibility of sobering up Williams for the second show, Pearl and the promoter’s wife drove him around town trying to get him to sing along with them. Williams finally agreed, belting out the first line of his gospel classic “I Saw the Light.” But he only got through the opening line before stopping. “But that’s the trouble, Minnie,” he said sorrowfully. “There ain’t no light.”

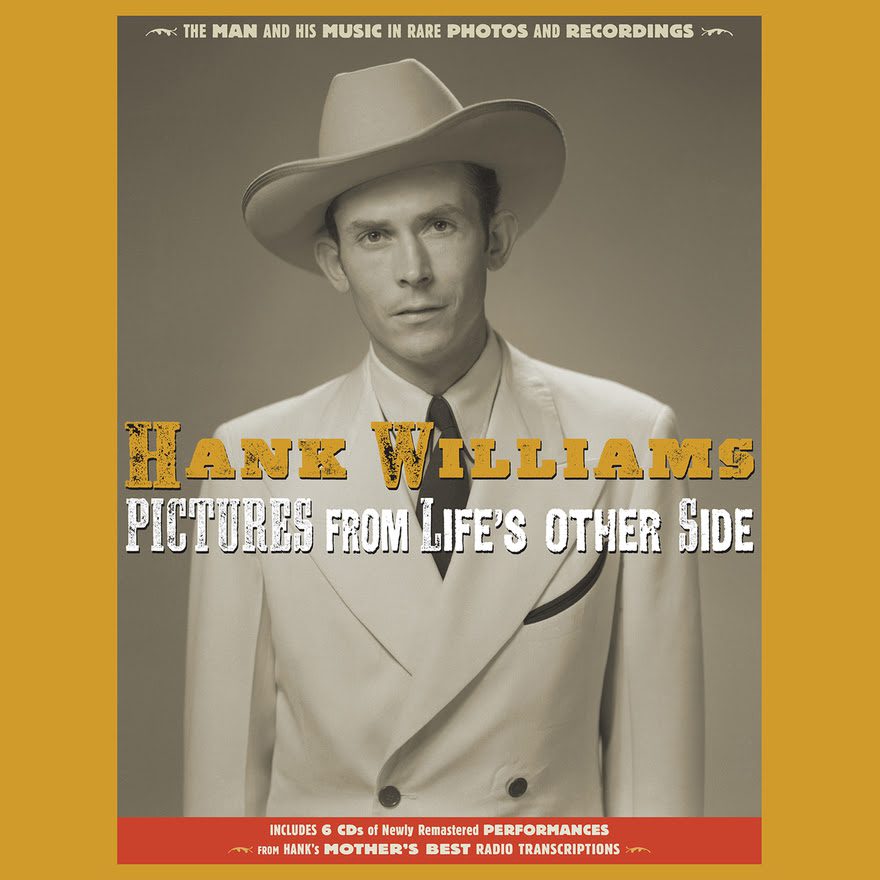

Williams’ tortured soul was reflected in his music, an outpouring of loneliness and pain unequaled in country music. A new six-CD box set, Hank Williams: Pictures From Life’s Other Side — The Man and His Music in Rare Photos and Recordings, features songs he recorded for his Mother’s Best Flour-sponsored radio show in 1951, reclaimed from previously unreleased discs salvaged from a dumpster. It’s accompanied by a 272-page hardbound book with rare photos showing the artist in all his raw and often disheveled glory. The 144 tracks represent an overview of Williams’ catalog, including “I Saw The Light,” “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” “Cold Cold Heart,” “Mind Your Own Business,” “Move It On Over,” and even rare recordings of a duet with wife, Audrey, on “I Hear My Mother Praying for Me.” There are a lot of covers as well: “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” Bob Nolan’s 1936 cowboy classic “Cool Water” (made popular by the Sons of the Pioneers), Tex Ritter’s “Dear John,” T. Texas Tyler’s “Deck of Cards,” Moon Mullican’s “Cherokee Boogie,” and Thomas Dorsey’s “Precious Lord Take My Hand.”

The cuts sound as crisp and clear as if they had been recorded yesterday, and the photographs are stunning. The most difficult to look at are the ones in the “Hank’s Final Year” section. By then, Williams had spent most of his life self-medicating from the pain of the spina bifida, which was exacerbated by a hunting accident in 1951 that further injured his back, and the “influence of outside causes” was taking a visible toll.

But most of the book shows Williams in happier days, posing with fans, his car, and onstage. For his lonesome, pain-wracked litany of tunes, Williams was paid the magnificent sum of a hundred bucks a week for five 15-minute radio shows in 1951, the equivalent of $950 today, and expenses had to come out of that. But Williams’ finances took off when “Cold Cold Heart” royalties started to come in that same year, and even though he was fired from the Grand Ole Opry in August 1952, he continued to make money on the Louisiana Hayride in person and on radio as well as from touring.

Maudlin but magnificent, Williams’ music set the bar high for heartbreak and misery, leaving generations of would-be country stars to wallow in his wake. These rediscovered old acetates capture Williams at his best, often high and lonesome, but always the king of misery.