Mark Rubin Explores Uneasy Borders of Jewish Identity and Southern Culture

There’s no better distillation of Jewish American identity couched in Southern culture than a 30-minute yarn seesawing between humor, horror, and rage relating to the ways the region’s legendary hospitality clangs with Jewish custom. For most Jews, “hostility” is the likelier word. For Mark Rubin, the Jew of Oklahoma himself, the luxury of just being plain old exasperated is welcome by comparison. Being Jewish in the Sooner State sounds an awful lot like being Martian anywhere in the United States: To everyone else, the stuff that makes you you is foreign, unfamiliar, or, to the yutzes in the crowd, weird.

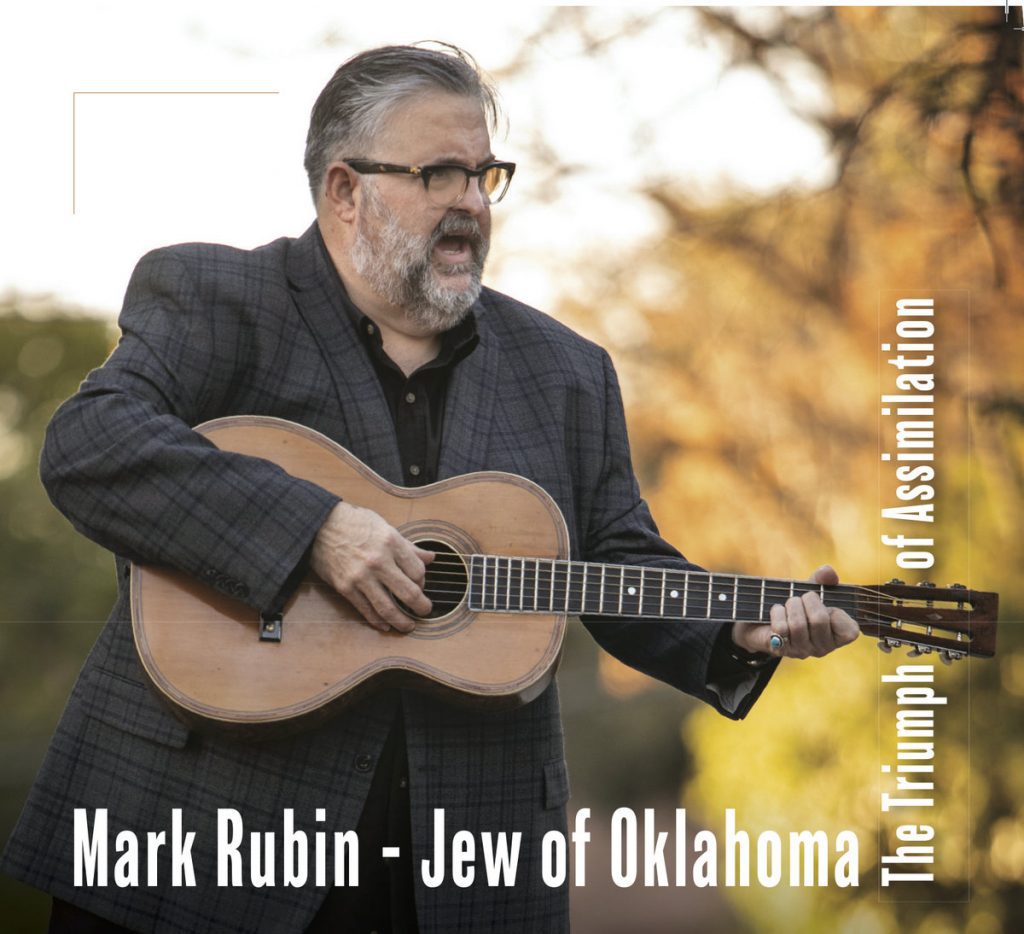

Rubin’s new record, The Triumph of Assimilation, functions like a “how-to” guide and warning sign for Jews living in the South, whether Oklahoma or Atlanta, where in 1915 a horde of braying white men kidnapped and lynched Leo Frank, the Jewish factory superintendent accused of murdering 13-year-old Mary Phagan. Frank, of course, was innocent, and his death encouraged Ku Klux Klansmen in waiting to emerge from their racist cesspools to burn crosses anew. “The Murder of Leo Frank” documents this great and little-known injustice, pointing a finger at Fiddlin’ John Carson for eulogizing Mary and stoking antisemitism with “Ballad of Little Mary Phagan” while essentially saying kaddish for Frank via strumming acoustic folk.

There’s a bitter irony to Rubin’s chosen aesthetic in “The Murder of Leo Frank”: Unlike The Triumph of Assimilation’s opener, “A Day of Revenge,” the tune is gentle, soothing, completely opposite to what a listener might expect from a song about bigotry by way of violence. On “A Day of Revenge,” however, Rubin belts: “Listen close to what I say / There’ll come a time, there’ll be a day / And though it seems so far away / I promise that we’ll make them pay.” An organ happily chirps over the verse and Rubin’s call for retribution. Meeting violence with yet more violence seems counterintuitive, not to mention antithetical to Judaism. (Look up “pikuach nefesh.”) But Jewish retribution isn’t violent at all. In Rubin’s estimation, the ultimate revenge is the cessation of war and the advent of peace. Now that’s Jewish.

Sarcasm and playful farce go a long way toward getting across Rubin’s frustration and bemusement, of course. On “Down South Kosher (A Dance of Hunger & Reconciliation”), a Klezmer-inspired recounting of the many obstacles Southern Jews following kashrut must either overcome or accept to maintain their diet, Rubin advocates treating bacon as a garnish and ham hock as a spice. “Unnatural Disasters” ticks off all the ills of the world people blame on the Jews, like global warming, with an upbeat tempo and good cheer. But The Triumph of Assimilation always comes back to that sense of frustration, the unifying detail binding the record together. In the South, Jews are acknowledged merely as Jews. Rubin’s radical argument is that maybe they should be treated as people. The album’s a hoot, but its enduring message remains firmly somber.