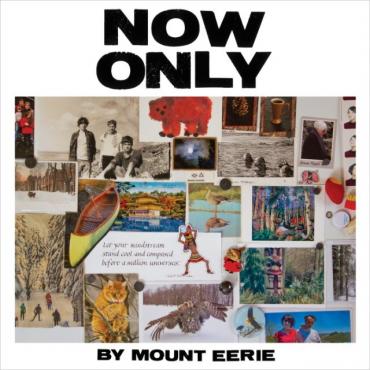

For Phil Elverum, aka Mount Eerie, the use of sprawling structures that resist or eschew conventional approaches (discernible verses, choruses, hooks) isn’t atypical, dating to his work with The Microphones. This signature is also apparent in earlier Mount Eerie projects, particularly 2008’s Dawn. The death of his wife, Geneviève Gosselin, in 2016, however, seems to have deeply impacted the content and tone of his songwriting. On 2017’s A Crow Looked at Me and his latest release, Now Only, Elverum occurs as eerily equanimous rather than volatilely restrained; atmospheres are austerely spacious rather than sonically repressed; and his focus is on everyday aspects of life rather than mythic arcs. That said, the everyday, in terms of Crow and Now Only, is set within the context of Elverum’s navigation of profound grief, so even though his images, anecdotes, and musings may ring as commonplace, the raison d’être of the project elevates the quotidian to the epic, Elverum documenting – in Zen-like and often prosaic language, as well as stripped-down instrumentation – his initiation into the realities of loss and ephemerality.

The literary analog to Crow and Now Only is Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, in which the author notes the mimetic distortions, dissociative tendencies, and Transrational or magical thinking that occur when one has experienced galvanic loss, in her case the sudden death of her husband. Didion’s book captures the tension between her pragmatic defaults and the impact of trauma on her thinking, the reality that her life (cognitively, emotionally, and logistically) has been irrevocably altered. Elverum too attempts to tether himself to “objective reality” while he navigates the trauma of losing his wife and raising their child on his own. He sings at the opening of Crow: “Death is real / Someone’s there and then they’re not,” voicing his intent to elude the temptations of illusion and fantasy – that one can remain connected with the dead in some quantifiable way.

His new album too opens with an intention to avoid the pitfalls of illusion: “I sing to you Geneviève / you don’t exist / I sing to you though,” Elverum offers on “Tintin in Tibet,” exploring the palpability of absence and the relentlessness of grief. His sparse guitar segues from the purely atmospheric into an intriguing picking pattern. Throughout the song, he reflects anecdotally on his relationship with Geneviève, throwaway details taking on sublime meaning given Elverum’s obvious desolation.

“Distortion” opens with a fuzzy guitar, a bright-ish acoustic emerging from the sonic rumble. “I don’t believe in ghosts or anything / I know that you are gone / and that I am carrying some version of you around,” Elverum sings, inquiring into the nature of death, identity, and impermanence. On the title song, Elverum ventures into satire (or perhaps sarcasm): “People get cancer and die / people get hit by trucks and die,” he sings, using a jingly tune that could have been penned by Stephin Merritt. Elverum addresses the precariousness of life via an upbeat chorus, verses devolving into confessional lyrics accompanied by minimal tones on the guitar and/or piano.

“Earth” opens with a lo-fi garage-y sound, grungy guitar, and ringing percussion, the backdrop quickly thinning to a sparse soundscape. Elverum continues to explore the nature of loss while offering snapshots of his and Geneviève’s child: “this dancing child who tears through the days / with a brilliance you would have deepened.” On “Two Paintings by Nikolai Astrup,” Elverum interpretively compares his own experience with grief and loss to elements and subjects in two paintings by the abovementioned Norwegian artist (for the sake of brevity, I’ve included links to the images and recommend listening to the song while viewing the two works, “Midsummer Eve Bonfire” and “Foxgloves”). The album closes with “Crow Pt. 2.” “Touching your last breath / reaching through to the world of the gone / with my hand empty,” Elverum concludes, affirming his enduring love for Geneviève and expressing his psychic transformation, that he now lives in both “the world of the gone” and the world of materiality.

As Mark Kozelek (Sun Kil Moon) used 2014’s Benji to masterfully explore the diaristic approach but, in my opinion, overemployed the method on 2017’s Common as Light and Love Are Red Valleys of Blood, so some listeners may conclude that Crow is more essentially focused and thematically cogent than Now Only. I’d be hard-pressed to adopt this view. While both albums draw from and explore the same (ongoing) experience, they do so from different emotional, philosophic, and artistic vantage points. Each album is successful in its own iconoclastic way. Taken as a diptych, however, A Crow Looked at Me and Now Only fully illustrate Elverum’s extraordinary vision, craft, and creative audacity, as well as vividly documenting the nature of grief – how trauma can be at once devastating and a source of inspiration.