Old Crow Medicine Show Proves the “Blonde” Tonic Still Zings after 50 Years

Like snake oil healers, Old Crow Medicine Show lays hands on Dylan’s myriad symptoms of unrequited or forsaken love, as detailed in his classic 1966 double album. Their zealously empathetic remake of Blonde on Blonde follows Dylan’s odyssey through the heart’s impossibly verdant wilds.

Since the late 1990s, Old Crow Medicine Show has helped forge the neo-bluegrass, old-timey band style since aped by the Avett Brothers, Mumford & Sons, and many more. None possess more joi de vivre or instrumental flair. So perhaps this historical convergence was as inevitable as a rush-hour car crash between a new songwriter in town aiming at outshooting the Music Row scribes, and a car full of Nashville session virtuosos drunk on the real thing.

Old Crow Medicine Show thrives on a lively, bounding dynamic of soulful ensemble, interplay and solos. Douglas Mason/Getty Images. Billboard.com

That’s sort of what happened in 1966 when Charlie McCoy, Wayne Moss, Kenny Buttrey, and other pickers ‘n’ kickers, including blind pianist Hargus “Pig” Robbins, tackled Dylan’s new songs. They ranged from the woozy opener “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35″ where Dylan’s lyric initiated a circular pot party (which the pickers may or may not have realized), to the long, closing meditation-in-your-beer “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.”

According to Rolling Stone reporter Daryl Sanders, the recording session began by Dylan setting the bar at an almost vertiginous height of poetic intoxication.

“This wouldn’t be another business-as-usual engagement. It was ‘Visions of Johanna’ — seven minutes and 33 seconds of Dylan’s muse at its most unfettered, full of dazzling phrase-making (Jewels and binoculars hang from the head of the mule) and profoundly suggestive pronouncements (‘Inside the museums, infinity goes up on trial’). For his part, keyboardist Bill Aikins recalls trying to understand what Dylan was saying in the song. It wasn’t like Nashville session cats — or those in any other city — typically found themselves contemplating lines such as, ‘See the primitive wallflower freeze / When the jelly-faced women all sneeze.’

“I thought it was really … far out would be the term I would have used at the time,” Aikins recalls, “and still today, it was a very out-there song.” 1

Anything but politically correct throughout, the set included the ultimate female stereotyping love song that remains hard to resist, “Just Like a Woman.” Dylan makes us think there’s a grain of truth in there, for the “she breaks just like a little girl” kicker line seems, to this day, an expression of irresistible empathy, love and respect for the woman he’s portraying so incisively, as I hear it.

A few songs earlier the songwriter laid his abject heart on the line, of course, with the stirring “I Want You.”

And “Stuck Inside of Mobile (with the Memphis Blues Again)” – with its insouciant, rattletrap groove and hit-the-rickety-breaks release to each new verse, resounds in many geographic and spiritual directions – a private, noirish hell riddled with nightmare details. “An, he just smoked my eyelids an’ punched my cigarette,” is a surreal yet comically-pointed image worthy of a slightly outre Woody Allen gag. (These two contemporaries remain among our greatest tough-but-milquetoast-statured culture geniuses.)

Or more pertinently to today’s headlines, the “Mobile” narrator reveals one brilliant way to do gun-rage catharsis that all too few have learned from: “He built a fire on Main Street and shot it full of holes.”

Ah, but the musicians on that song may have churned it so well by digging the feeling of cutting – musically and thematically – their peers in a competing Tennessee music city (Memphis, not Mobile).

Let’s down-shift a bit to the present recording. On “Obviously True Believers,” the Medicine Show pickers and fiddlers make us believe the power of their bluegrass/newgrass to hold its own energy in a reflective chrysalis, embracing those original sessions, even to release the music like a new sort of winged beauty.

They’re facing a high bar, here, too. Like The Band (then known as The Hawks), Dylan’s chosen collaborators back North, OCMS is three-lead-singers strong. Nobody today can match The Band’s craggy-hillside three-part vocal harmony, notably when covering a Dylan song or backing him. And no single band matches Rick Danko, Levon Helm, or especially Richard Manuel, as lead singers. Is that unfair to note? The younger band surely and humbly understands how The Band influenced them.

But the remade Blonde is more about solo vocal takes and, in lead turns, these singers (Ketch Secor, Critter Fuqua and Kevin Hayes) vocalize with at least as much passion as Dylan did, but without his accompanying layers of nuanced and biting tonal irony.

I love their ardor and fire, and how they up the ante with energy. Yet, it’s like they’re in love with these songs like would-be or lost lovers. So it’s cool to be aurally reminded of Dylan’s genius and how superbly his songwriting fit the Nashville players’ ratty-holed couching of it. As with any good tribute remake, the new album should send you back to the original, not just to accept this as a substitute.

Dylan let Blonde on Blonde grow across the Tennessee hills and worm itself into the collective consciousness, with roots as abiding as the tides of time. So it was that this project arose, half a century down Highway 61’s ever-worn path, from his native Minnesota to the deepest South where most of his favorite musical vernaculars came from. But he’s too great of an American poet and visionary to leave his roots at that.

Not coincidentally, another American road introduced this great band for me when Ariana Karp, the daughter of my photographic collaborator Katrin Talbot, popped Old Crow’s first CD into the car player some years ago. We were headed East in research quest of Herman Melville, for my book about the great American novelist-poet-visionary never quite recognized as such in his time. Melville is also deeply ingrained in Dylan’s experience, from his evocations of Ahab on Bringing It All Back Home to his description of Moby-Dick in his recent Nobel Prize-winning speech:

“He pursues the whale around both sides of the earth; it’s an abstract goal, nothing concrete or definite. Calls Moby the Emperor, sees him as the embodiment of evil. Ahab’s got a wife and child back in Nantucket that he reminisces about now again. You can anticipate what will happen.”

You sense the affinity of Dylan’s own restless search, to grapple with his own demons just ahead of him, and his better angels following warily behind, a search which has proven amazingly fecund over these years, for avoiding self-destruction. And Ahab’s wife is his own “girl from the north country,” and Dylan’s own is Sara Lownds, whom he had only wed shortly before he took off for Nashville to tip the world’s balance in his sprawling musical adventure.

He’d revisit his exquisitely-doomed Nashville romanticism after recovering from his real-life, near-fatal motorcycle nightmare, to finally record the kinder, gentler Nashville Skyline, which sits in history right behind Dylan’s healed motorcycle ass, even as the mythical John Wesley Harding remains his “healing up” transition album. What heady times these were for the forming American “roots music” genres (along with The Band’s efforts, among other things) and they were not lost on the members of Old Crow Medicine Show.

You can’t help feeling that way, after hearing this, or perhaps seeing them live (they just performed the album in Milwaukee on June 9) as this is a triumphant live recording at the Country Music Association Theater Fame in downtown Nashville. Nearby stands The Johnny Cash Museum dedicated to the only actual country music contemporary of Dylan’s who could go toe-to-toe with him in Cash’s lifetime, and on Nashville Skyline. OCMS band member and album annotator Ketch Secor conveys how the band grappled with time’s motion captured in amber, which itself bounces and tumbles down the river. Secor writes: “50 years is a long time for a place like Nashville, Tennessee. Time rolls on slowly around here like the muddy Cumberland River. But certain things have accelerated the pace of our city. And certain people have sent the hands of the clock spinning. Bob Dylan is the greatest of these time-bending, paradigm-shifting Nashville cats.”

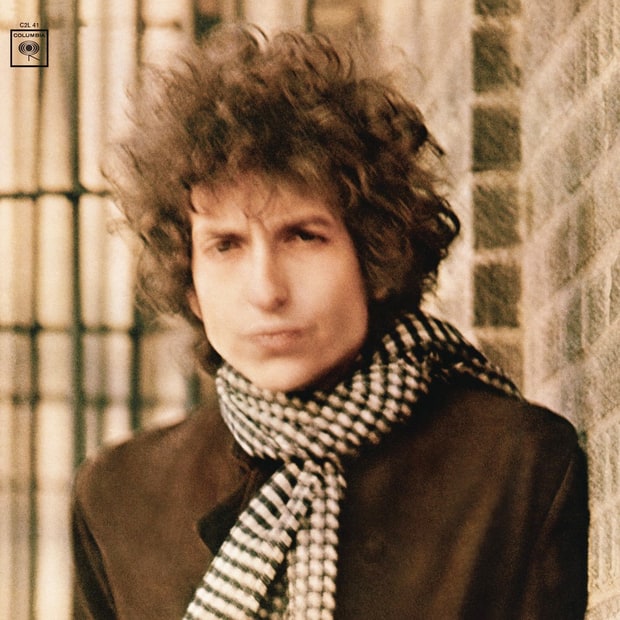

So a paradigm shifted in the slightly askew but inevitable collision that produced a strangely beautiful music that few ever anticipated, maybe not even Dylan himself, then a 25-year-old explorer of American vernaculars and poetics. The shift seems signified in the slightly out-of-focus photo of Dylan on the album cover.

The original cover photograph of Dylan’s epic “Blonde on Blonde” double album. courtesy amazon.com

And Secor writes outright he “loves” Dylan twice, and the artistic bromance probably septuples among OCMS members. So we’re talking “doomed,” improbable and inevitable romance, once again, of a different stripe. “The greatest spinner of rhyme and couplet since Shakespeare,” Secor rhapsodizes, and that remains debatable, but also now as inevitable a discussion as the Nobel Prize for Literature for the first pop songwriter. That raised some already high literary brows but solidified the assertion on an international Rock of Ages. So these guys clearly love the songs and cranky old Bobby Dylan, if not various real or mythologized women.

The result is this exuberantly loving re-imagining of the time a pop music artist knew he had two albums worth of strong stuff, especially when he found his Nashville cats. Amid long, arduous sessions often going deep into wee hours, the original studio players had their limits, being accustomed to three-or-four minute recordings. They admittedly seemed to run out of gas in the closing verses of the original 11-minute-plus “Lady.” 2

But Dylan clearly was setting new boundaries for a recorded rock music statement. So, with a gulp of extra literary oxygen at that point, we can see that “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” counterintuitively stands tallest of the songs. The lady-on-a-pedestal looms like a mythic goddess of shadowy ardor engulfing the countryside. 3 This time, the younger band that began by busking on New York city streets in 1998, have plenty of wind to the end.

Dylan asked repeatedly of his lady, “Should I wait?” Through yawning glens the “medicine show” echoes – singing, sighing, crying. Time waits and heals wounds and cultural schisms, over 50 years and beyond.

Today, when the rural South and much of the urban seem worlds apart from Dylan’s hip New York street corners – much less the hallowed judgements of the Nobel Prize – Blonde on Blonde retains a lasting, redemptive power. The twains did meet in 1966, and the times changed forever.

__________

2. How hard did these musicians work to realize the simmering creativity of Dylan, who reportedly worked on little more than Cokes and chocolate bars during the long sessions? They went along with his idea to get a more “ramshackle sound” for “Rainy Day Women,” first by bringing in a trombonist for the song’s “wha-wha” effect, reports Andy Gill in Dylan: Visions, Portraits and Back Pages (Dorling Kindersley, 2005). Then Kenny Buttry disassembled his drumkit and deadened his snare drum to approximate the sound of a marching band drummer. Charlie McCoy also performed a dazzlingly ambidextrous party trick of playing bass and trumpet simultaneously, one in each hand. The ultimate story of the epic Blonde on Blonde sessions is found in Chapter 4 of Sean Wilentz’s remarkable history Bob Dylan in America (Doubleday, 2010).

3. “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” is ranked as Dylan’s third-best song ever in the critical anthology Dylan: Visions, Portraits and Back Pages, characterized there as “Eleven minutes-plus of serpentine psychodrama.”

A short version of this review was originally published in Shepherd Express.