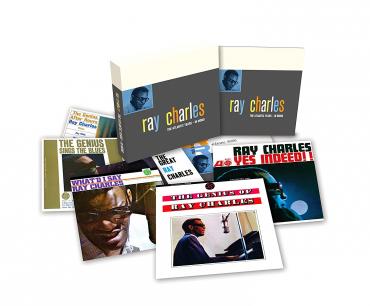

Ray Charles’ Atlantic Box

He could get more out of a moan than many singers could wring out of a career. Ray Charles was the voice of pain, agony set to music that bared his soul and exposed his genius to the world.

Rhino Records has resurrected Charles’ early years on Atlantic with a box set of seven vinyl albums spanning 1957 through 1961, remastered from the original mono tapes. For those of you born too late, mono mixed all the sound in a single channel, as opposed to stereo using two or more independent audio channels, usually separating guitars and vocals to the right speaker and everything else to the left. So mono sounded like the band was all in one room, a more concentrated sound that still revealed nuances of sound that often didn’t come thru on stereo recordings. The upshot is that whether the perception is rooted in nostalgia or based in reality, mono just sounds better to us old-eared people.

Charles is displayed here in all his soulful, groaning glory. There are two offerings from 1957. His Atlantic album debut, Ray Charles, is the most interesting for r&b fans, containing Charles’ hit singles from ’52- ’57. “Ain’t That Love” is gospel soul with the Rae-lettes as a soulful choir behind him. “Drown in My Own Tears” is an unlikely mashup of blues, big band, soul, gospel, and country, with a smooth horn section gliding behind him and the girl gospel choir once again making it churchy. The breakout single here was “I Got A Woman,” a song Charles admitted adapting from an old spiritual he thinks might have been called “I Got Jesus.” But there’s no mistaking the focus here is on secular, not celestial matters, as Ray preaches about what his woman saves up for him early in the morning, his sermon punctuated by David Fathead Newman’s sax. “Mary Ann” sounds like Fats Domino’s “Hello Josephine,” but with some serious renovations. It starts out with a laid –back calypso clop then changes to hard-core, horn–backed swing before clip-clopping back into a tropical rhythm.

The Great Ray Charles is an all instrumental jazz album, with Quincy Jones co-arranging and composing one tune, “The Ray,” that jumps around pretty good big band swing style. Horace Silver’s “Doodlin’” lives up to its name, and “My Melancholy Baby” shares the same swinging big band sound as “The Ray.” It‘s great stuff, David Fathead Newman‘s saxes conversing instrumentally with Charles’ piano.

There are seven LPs here, each revealing a different side of Charles’ genius. Yes Indeed is a collection of singles from ‘54- ‘58. The title cut is the most recognizable, but “What Would I Do Without You” is an interesting recipe, Charles’ bluesy, heartbroken, soulful moan juxtaposed with a county–flavored piano accompaniment that sounds like it might have been the inspiration for the melody on Kitty Lester’s ’62 hit, “Love Letters Straight From Your Heart.”

But for down and dirty, gospel-soaked soul, you can’t top “I Want To Know,” his backing girl group the Raelettes lining out the responses to Ray’s call, answering “yes, yes, yes,” to his come-ons.

Genius Sings the Blues standout cut is a song that sounds related to “I Want to Know, built on the same framework. Nappy Brown always claimed Charles usurped “Night Time,” which he had written and released the year before. Charles gave Brown writing credit, but once he wrapped his tonsils around it, it belonged to him. Even when Charles taps Raelette Margie Hendricks to come forward and do some sermonizing of her own and she takes a blowtorch to the proceedings, scorching the stage, the piano and the mic with her own fiery come-on, Ray still manages to pull it back and stay in the spotlight with his gloriously fractured vocal on this piano-pounding ode to sin.

’59’s What’d I Say of course revolves around the title cut, a song Charles made up on the spot when the band ran out of tunes about fifteen minutes short of his allotted time on a gig. Censors clamored for Charles’ frenzied vocalization of the sex act to be banned from the airwaves, but all it did was give Charles bigger fame and a lifetime set–ender.

The personnel on The Genius Of Ray Charles reads like a who’s who of jazz, including trumpeter Clark Terry, with Zoot Sims and David Fathead Newman on saxes, Duke Ellington trombonist Quentin Jackson, and two Count Basie orchestra veterans, guitarist Freddie Greene and bassist Eddie Jones. Alongside standards like Johnny Mercer’s “Come Rain or Come Shine,” and Irving Berlin’s “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” Charles and his jazz allstars lay down the rockinest big band version of “Let The Good Times Roll” ever recorded.

The title cut from ’61’s all instrumental The Genius After Hours is a laid–back, late night bluesy keyboard musing, fit for a smoky cabaret in the wee hours. Taken from the same sessions that provided material for The Great Ray Charles, After Hours also boasts a version of “Ain’t Misbehavin” that Charles wanted to cut to rival Miles and Coletrane’s success with ballads. David Fathead Newman’s tenor is as big a star here as Charles’ piano, late night lonesome pouring out of his horn.

This is what genius sounds like, beautifully preserved in 180- gram vinyl. It’s substantial stuff that feels as good as it sounds no matter how many times you heft it up and drop the tone arm on it. Yes, indeed.