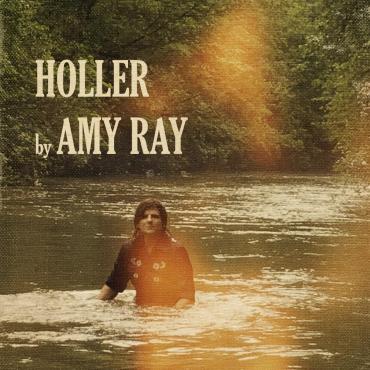

Amy Ray’s new album Holler is meant to be played loud. Some of the tunes fly right out of their grooves, propelled by raucous, joyous, straight-ahead, guitar-fueled rhythms. Others shout, even amidst their gentle country vibe, about injustice and shake us to look at the world around us and to embrace our activism within it. The title, after all, cuts many ways. A holler is a little secluded, isolated impression in the mountains or hills, but it’s also a scream that defies the desire for isolation and insularity. As Ray says, “There’s a lot of different things that the title means. It’s kind of in the vernacular. It’s also this need in our country where we need to holler. I intended this record to be a “holler” vibe; I wanted to be provocative. I feel like I’m ready to merge the country stuff I’m doing now with the punk stuff I used to do. Simple chord progressions with complex lyrics.”

Holler developed organically over the past five years or so, with Ray and her band playing several of these songs at shows. “It was time to make this album,” Ray says. “The band that played on the record was the band that’s been playing with me for four or five years; we felt comfortable. I had the songs, we were rehearsing the songs over the years. We recorded live to tape, and we recorded it at this insane rate. We did strings and horns of this one, but we hadn’t ever done that.”

The album opens with a gorgeous waltz, “Gracie’s Dawn,” whose piano trills echo “Moon River,” but this lilting prelude quickly rockets off into the stratosphere with a steel guitar-drenched rocker, “Sure Feels Good Anyway.” The richly layered minor-chord sonic musical structure mimics the defiance in Ray’s vocals. Jeff Fielder’s crisp lead notes float over blaring horns and capture the contradictions between the warm feelings of coming home to a familiar place and the painful feelings of not being accepted in that home: “I know you don’t like me / But it sure feels good anyway.”

“I wrote ‘Dadgum Down’ on the banjo,” says Ray. “Alison Brown and Jeff Fielder started this whole interchange and built the song around that.” It’s a layered tune that echoes the sadness of a broken relationship or reaching the rock bottom. “Last Taxi Fare” opens with a phrase that recalls Stephen Stills’ “Change Partners” and floats on a bridge that recalls the “Theme from the Last Waltz.” The entrancing beauty of the song envelops a tale of surprises and revelations. “It’s based on an experience I had,” Ray recalls. “I ended up in this taxi late at night, and the driver asked it would be okay if he picked up another fare. This drunk guy got in the cab. I had friends that were having issues with addiction, and I was still working to live out my sobriety. This situation pushed a lot of buttons. I started writing a song in my head about it, though. You don’t even know what packages your angels come in, I thought. It’s typically in things that you hate.”

Ray wrote “Sparrow’s Boogie,” an urgent rocker with the vibes of an old-time fiddle reel, as a tribute to the Georgia poet Byron Herbert Reece. The song’s cinematic quality brings to life the words and images Reece strove to communicate in his poetry: “It didn’t matter to him if he was hungry, sick or tired / He gave words to the wordless … / If I could tell you a thing or two / Every seed that you sowed, every word that you wrote / Brought another sparrow home.” Ray recalls that she didn’t know about Reece when she moved to Dahlonega 25 years ago, but someone gave her a book of his poetry. “I was fascinated by his life and struggles — he was trying to be subversive about race — and the beauty of his language, his turn of phrase. He was speaking for all these objects that couldn’t speak for themselves,” Ray says.

The down-home, hand-clapping old-time gospel song “Jesus Was a Walking Man” floats along the tide of Alison Brown’s banjo runs; Rutha Mae Harris of The Freedom Singers delivers a powerful little sermon toward the song’s end. “Jesus is like this fixture in my life,” says Ray. “He’s the embodiment of all things activist for me. I took the gospels and Jesus seriously and they influenced the activist in me. I want to be like this guy; he’s helping the sick and the poor — that’s the story I cling to, that’s the myth I’ve used to get through. I needed that person in my life. I’m a pagan nature lover who believes in a higher power.”

The joyous “Tonight I’m Paying the Rent,” with its celebratory boogie-woogie piano and its hearty choruses, should be the troubadour’s anthem, as it points both to the struggles and the joys of a modern musician, and the community of all those others traveling the same road. Matt Smith’s pedal steel riff on the bridge channels John David Call’s steel guitar on Pure Prairie League’s “I’ll Fix Your Flat Tire, Merle.”

As Ray’s fellow Georgian Flannery O’Connor once said, “to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost blind you draw large and startling figures.” On Holler, Ray, like O’Connor, hollers so that we can’t fail to hear the voices of the voiceless. She tells such compelling stories that we can’t fail to recognize our own shortcomings or to acclaim the actions of those who overcome systemic evil or strive to incorporate their shortcomings into their lives in a redemptive way. Ray delivers these stories and portraits in heart-wrenchingly beautiful ballads, raucous rockers, and joyous old-time country gospel songs.