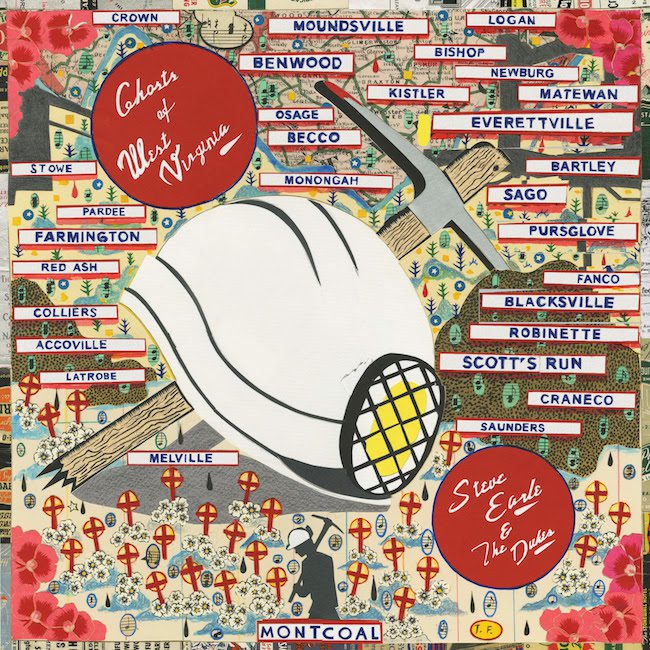

Steve Earle Invites Listeners to Commune with the ‘Ghosts of West Virginia’

In the liner notes for his 2015 record, Terraplane, Steve Earle wrote, “[The blues] are very democratic, the commonest of human experience, perhaps the only thing that we all truly share.” Though his latest album, Ghosts of West Virginia, may feel more at home in the folk genre than blues, it will be prized as an unforgettable venture that connects listeners to a profound human experience. On April 5, 2010, a coal dust explosion at the Upper Big Branch coal mine in the small unincorporated town of Montcoal, West Virginia, took the lives of 29 miners. A decade later, Earle tells the stories of those miners and their homeland for the whole world to hear.

Ghosts of West Virginia took shape after Earle was approached by two documentary playwrights, Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen, about their project surrounding the explosion. Together, they embarked on a journey to West Virginia to interview the two men who survived the blast and the families of the miners who died. Blank and Jensen took these interviews and crafted stage monologues; Earle took these interviews and turned them into seven songs that would serve as the guide for the monologues. Out of that came Coal Country, a musical that made its debut at the Public Theater in New York City on March 3, and whose run was cut short due to COVID-19. Whether or not the musical will return to the stage — Earle and company are hopeful — the stories and experiences of Coal Country are deeply rooted in and forever captured on Ghosts of West Virginia.

Opening with the original gospel track, “Heaven Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” Earle and his band The Dukes — guitarist Chris Masterson, fiddler Eleanor Whitmore (who sings the striking and heartbreaking “If I Could See Your Face Again”), pedal steel all-star Ricky Ray Jackson, bassist Jeff Hill, and percussionist Brad Pemberton — set the stage for a poignant and, at times, unsettling trek to Montcoal. “Don’t worry about puttin’ nothin’ away / Heaven ain’t goin’ nowhere,” Earle and company sing on the a cappella tune. “Money’s no good come the judgment day / I reckon Heaven ain’t goin’ nowhere.”

The next six tracks take listeners through the songs that make up Coal Country. (The final three songs don’t directly relate to the Upper Big Branch disaster, but rather they tell other stories of West Virginia.) As Earle noted when this album — his 20th studio effort — was first announced, “The actors don’t relate directly with the audience. I do. The actors don’t realize the audience is there. I do.” Earle’s presence, whether on stage or in the grooves of the record, is unshakable and unparalleled.

Easily the most stunning moment on Ghosts of West Virginia comes in “It’s About Blood,” an ode to the sacrifices made by the working men of Montcoal. Whereas a gospel hymn might focus on the power of the blood of Jesus Christ, Earle turns his attention toward the overlooked significance of the shed blood of those 29 men, each of whom are named by a righteously angry Earle as he closes out the song.

By the end of the album, Earle has invited listeners into the experiences of the explosion and its aftermath, but perhaps most powerfully, he’s created a world that is inhabited not just by those directly affected by the horrific event, but by all who have ears to hear. It’s a shared experience that crosses state lines, destroys privilege, and transcends time, and it will live on as one of Earle’s finest pieces of work of his career.