Still Willie After All These Years

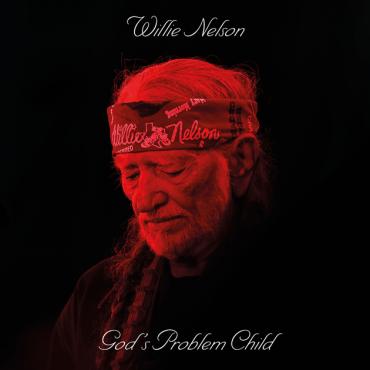

Here’s hoping that Willie Nelson has a dozen more albums left in him. But he’ll have trouble equaling the richness and emotional depth he has achieved here, with God’s Problem Child (out April 28 on Legacy). The album’s cover recalls the era when Willie was at his creative peak, when 1974’s Phases and Stages led to his popular breakthrough with the next year’s Red Headed Stranger. Yet the intimations of mortality throughout this material show that he knows such sustained brilliance was half a lifetime ago, and that some fans have wondered ever since if he could approach it again. He could, and he has.

Nelson and producer Buddy Cannon wrote more than half the material, a collaboration that has served the artist well, while some of the album’s standouts are songs he didn’t write, but could have. Like the opening “Little House on the Hill,” a sprightly, call-and-response spiritual, with the chirp of Mickey Raphael’s harmonica providing as much of a sonic signature as Nelson’s staccato guitar and conversational, behind-the-beat phrasing. It was written by Lyndel Rhodes, Cannon’s 92-year-old mother. Sign her up.

The album’s thematic linchpin is the next number, “Old Timer,” co-written by Donnie Fritts, which has the artist acknowledging what he has become, how the world sees him. “You had your run,” he sings without regret or resentment. “It’s been a good one. Seems like the world is passing you by.” The flip side of that sentiment comes later, with “Not Dead Yet,” funny in a pointed way, given the poor health that has forced Nelson to cancel dates and the rumors that always circulate. “Don’t bury me today, I’ve got a show to play,” he sings.

The bluesy, ruminative title song finds Nelson trading verses with co-writers Jamey Johnson and Tony Joe White, exploring a dark place musically where Willie on his own rarely treads. It’s timeless in the same way that the album’s classic country waltzes are. Except for the contemporary hook to “Delete and Fast Forward,” Willie is still making the same kind of music he made in the ‘70s, though perhaps he hadn’t experienced enough, or aged enough to make music then that is as weathered as this.

Concluding the 13-song album (which is perhaps two or three songs too many) is the obligatory tribute to Merle Haggard, with whom Nelson long recorded and toured. “He Won’t Ever Be Gone” was written by Gary Nicholson from Nelson’s perspective, and the artist delivers it with just the right emotional pitch—sincere, but now wallowing in sentiment, with the recognition that Merle’s fate awaits Willie, awaits us all. And yet Nelson throughout sounds as unburdened as ever, contemplative but satisfied, but knowing that these songs well played reflect a life well lived, and whenever is has to end, so be it. He won’t ever be gone.