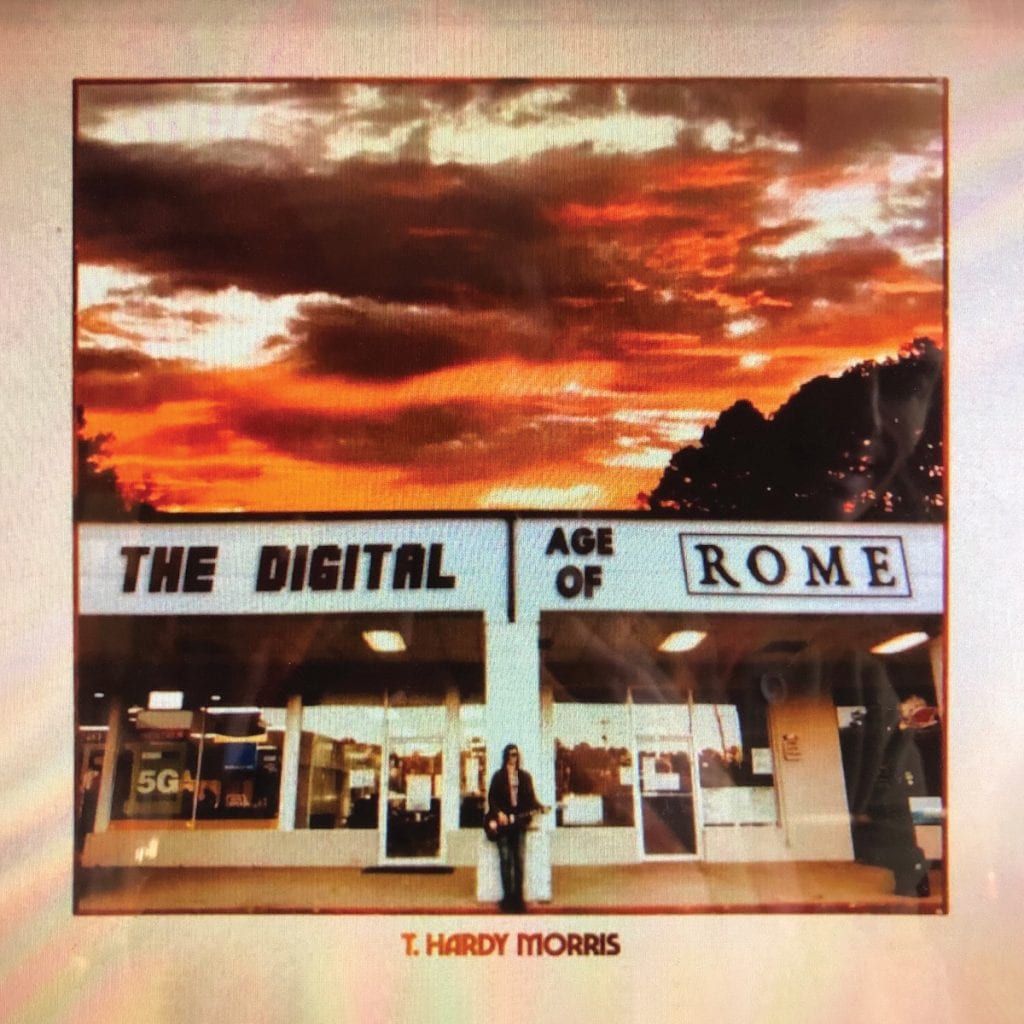

T. Hardy Morris Sizes Up Society with a Smirk on ‘The Digital Age of Rome’

There is beauty in cynicism. T. Hardy Morris knows this. His latest record, The Digital Age of Rome, takes a dark, gritty look at a society on the brink of collapse due to an overload of technology and performative living on social media. Morris captures all the worst parts of ourselves during a year on lockdown when we all spent far too much time glued to screens, ultimately coming away with a greater sense of what’s really important to him. Scrapping the songs he’d demoed for his follow-up to 2018’s Dude, the Obscure, Morris started over, writing about the things he was seeing around him through a lens of dissolution, but with shimmery arrangements of hazy pop rock.

The ruminations that populate Morris’ songs range from the constant need for something shiny (“New New New … Next Next Next”), anxiety over too much time spent at home near neighbors (“Down & Out”), and finally cutting all the bullshit and showing his true self to weed out the phonies (“Fake Gold”). Fuzzy guitars play nice with mellow steel guitar, and supporting vocals from Faye Webster, Shelly Colvin, and Adam Landry elevate Morris’ own gorgeous stoner howl. Though Morris’ lyrics are weighed down by capitalism fatigue and the carelessness of humanity, his songs are airy and dreamy, almost making the pill easier to swallow. Just look at “Shopping Center Sunsets,” a laundry list of things to waste your money on — “bad gringo Tex-Mex,” “lay-away dinette sets,” “discount aquatic pets,” “tribal tattoo concepts” — delivered in one of the album’s most captivating melodies. Though he sings about filling an emptiness with needless things, we’re hypnotized, visualizing the “deep magenta sky” he paints for us like we’re right there, hands full of plastic shopping bags.

The Digital Age of Rome is Morris at peak songwriting. These haunting thoughts of his stick with you, probably because you’ve had them, too. “Fall for lust / hope for fate / fight to live another day,” he sings on “First World Problems,” encapsulating the self-destructive tendencies inherent in all of us in just a few short phrases. In the bleakness of his observations, he ends up connecting with us.