The Final Curtain: Elvis Way Down in The Jungle Room

Few American artists could claim territory in the national spirit like Elvis Presley. In a country where identity undergoes a constant process of multiplication and fluctuation, Elvis managed to pull everything together into a cohesive persona and performance. He was white with a black influence. He was masculine with a feminine side. He was rural and urban. He was a pioneer of the sexual revolution, but a deeply religious gospel singer. In life and music, Elvis evaded category and refused to adhere to any of the petty boundaries and borders that people of small imagination and weak heart honor. He was the “I” of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass: A living, breathing, and singing contradiction, “full of multitudes.”

Whitman was not writing about himself as much as he was writing about America, and Elvis is an American icon for precisely the reason that he, more than any other singer who preceded or succeeded him, rhapsodized every American contradiction into a captivating medley of rock ‘n’ roll, soul, funk, folk, gospel, blues, and country.

The country music of Elvis never receives the attention or acclaim that it deserves. Gospel and country were his first two greatest loves growing up in Tupelo, Mississippi. It was only after the Presley family moved to Memphis that he discovered he had equal love for the gospel emanating out of black churches, and the rhythm and blues reverberating out of the Beale Street clubs.

As not the inventor, but one of the founding fathers of rock ‘n’ roll, he earned the nickname, “The King of Rock,” and is much more associated with the genre he helped create than any other. Even most Elvis fans might not fully appreciate that in his 33 year recording career, Presley scored 25 top ten country singles.

There is a poetic grandeur and beauty to the triumph and tragedy of Elvis’ short life, and one dramatic element of the story is that for his final recording sessions, he returned to the music he first loved as a child: Country and Western. He and his band’s delivery was more modern than the rustic, rural sounds that filled his head in Tupelo, but it was loyal to the soul of the south. Another often overlooked aspect of Elvis’ life and career is the importance of the Southern United States. Because he is a pop cultural legend of international repute, it is impossible to relegate Elvis to a particular region, but he was as Southern as Memphis barbeque or Mississippi mud.

In 1976 and ’77, the King’s throne was sinking into the dirt. His health on the decline, his drug dependency on the rise, and his mood often despondent, Elvis resisted record company requests for new material, because he did not want to venture outside of Memphis. Stax Studio, where he continued to master his own innovation – rhythm and country – with a brilliant blend of funk, soul, and Americana in 1973, was now shut down. That left a reclusive Elvis with few options, and had his record company executives feeling desperate. RCA decided to park a big truck, one much larger than what he drove around Memphis making deliveries before he became music’s biggest star, outside of the Graceland mansion, and turn Elvis’ surreal Jungle Room into a makeshift recording studio. Elvis would now need only walk down the stairs to record a new album. In a few cases, he took full advantage of the convenient arrangement, singing into his microphone, hair unkempt, wearing nothing but his bathrobe.

For the last recordings before his death, Elvis sang from his home and he returned to his home.

The results are largely a powerful exhibition of a man, who despite his slightly diminished capacity, still had more soul and strength than most singers could ever dream. Comparisons to earlier recordings from the late 1960s and the early 1970s, like the aforementioned Stax sessions, and the masterpiece material of From Elvis in Memphis and Elvis Country: I’m 10,000 Years Old, reveal a weakened voice. The magic, however, had not left the building. There were just fewer tricks left in the bag.

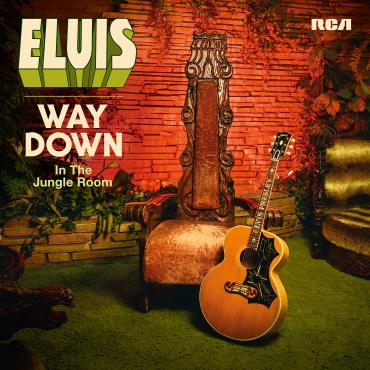

RCA Legacy has now released all of these tricks and tunes in the deluxe, two disc package, Elvis Way Down in the Jungle Room. The RCA Legacy editions of Elvis Presley music have become a treasure chest for Elvis fans. Full of remastered recordings, studio outtakes, alternative versions of familiar favorites, and beautiful booklets with extensive liner notes and photography, these packages always rise to must have status for anyone interested in Elvis. Way Down in the Jungle Room is no exception.

The historic value, alone, of the recordings make it an essential purchase. To hear Elvis, with the TCB Band, and all of his majestic singers, loose and lusty in the newly equipped home recording studio is to get great insight into how Elvis’ passion for musical creation and innovation never died, and how his personality, despite all of his late-life troubles, maintained its charisma and allure.

In an alternative universe, if this set comprised the debut recordings of an otherwise unknown singer, the unanimous critical evaluation would crown him one of the greatest vocalists to emerge in the late 1970s. The younger Elvis, in some cases, is the worst enemy of the older Elvis. “Way Down” is a fun and frenetic rock song kicked into high drive with libidinous power, but pales in comparison to similar Elvis songs like, “Patch It Up,” “Got My Mojo Working/Keep Your Hands Off It,” and “Burning Love.” “Moody Blue” is a delightful hybrid of country, pop, and soul, but the earlier Elvis mastered such songs like “Suspicious Minds,” “It’s Your Baby, You Rock It,” and “I Got a Thing About You Baby.”

There are moments, scattered through the two discs, when Elvis sounds lethargic, most especially on the more maudlin material like “Solitaire” and “Never Again.” For reasons that will always remain mysterious, the histrionic “Hurt” became a fan favorite from Elvis, but side-by-side with much stronger material, it becomes a burden to hear.

Despite these unfortunate choices and selections, the good and the great far outweigh the bad. The alternative version of “She Thinks I Still Care” – a honky tonk barnburner of country rock featuring a ferocious performance from Elvis – is one of the greatest numbers that he ever recorded. “Bitter They Are, Harder They Fall” is an emotional ballad, in the style of “Just Pretend,” that demonstrates Elvis’ capacity for drama and soul in service of mapping the mysteries of the human heart. His version of “Pledging My Love” is a rhythm and country rendition as irresistible as it is effectual. “For The Heart” more than makes up for the mediocrity of “Way Down.” When Elvis tears into this country-rock song, he leaves nothing behind – thundering out the opening line, “I had a dream about you, baby,” as if he is singing for his life. His avidity and energy are miraculous considering that, according to biographies of Elvis, he tore into the few takes of “For The Heart” immediately after rolling out of bed, and tightening the rope on his robe.

The 16 songs of the Jungle Room recordings spawned two separate releases in the last two years of Elvis’ life – From Elvis Presley Boulevard, Memphis, Tennessee and Moody Blue. “Way Down” and “Moody Blue” were number one country singles, and “Hurt” rose all the way to number six on the country charts. The success of Elvis’ last recordings is sufficient to stimulate speculation into whether Elvis would have become the king of country had he regained good health. Having conquered and seemingly lost his interest in rock, he could have easily become one of the most popular and profound country hitmakers of the 1980s.

Instead of transitioning into a fourth act, Elvis left the building forever. He gave the world a lifetime of amazing artistic achievements, and his closing moments are on the Jungle Room sessions.

On the last night of his life, Elvis sat down at his home piano, and played a handful of songs before retiring to his bedroom. Family, friends, and biographers believe that two of the last songs Elvis ever sang on Earth were “Unchained Melody” and “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.” The lyrics of each were propped up above the keys the morning that Elvis died.

A soulful and evocative “Blue Eyes Crying in The Rain” is one of the showstoppers on Way Down in the Jungle Room. Elvis leads his band and singers through a version equally at home in a honky tonk or soul music festival. The synthesis of black and white, rural and urban, and country and soul was something Elvis could perform up until his final heartbeat. It was that thud inside his chest that provided the backbeat to every song he ever recorded, and it could make no distinctions between cultural classification or musical identification.

“Blue Eyes Crying in The Rain” might have been the last song Elvis ever sang, but the last song he recorded was an intimate and intense performance of the 1959 country hit, “He’ll Have to Go.” The late night, bar stool appeal to a woman whose affection has turned to another man allows Elvis to make perfect use of his baritone. James Burton plays a country guitar so low it could clean out the plaque in anyone’s artery, a bass and soft drum stomp along, and Elvis goes from the basement to the mountaintop in his vocal delivery. It is an unexpected triumph from Elvis Presley, who clearly was still capable of using his unique and unprecedented vocal talent to communicate in the frequency most audible to the human spirit.

All of the songs on Way Down in the Jungle Room, like during previous recording sessions, were recorded live. Elvis garnered the most enjoyment from the elevation his own spirit felt when surrounded by the sounds of his handpicked players and singers. The young death of Elvis is one of American music’s great tragedies, but the beauty and brilliance of his final notes is one of its least appreciated stories.

He didn’t have to go, but he did. The music remains forever.

David Masciotra is the author of Mellencamp: American Troubadour (University Press of Kentucky) and Metallica (a 33 1/3 book from Bloomsbury). He is currently at work on the forthcoming, Barack Obama: Invisible Man (Eyewear Publishing).