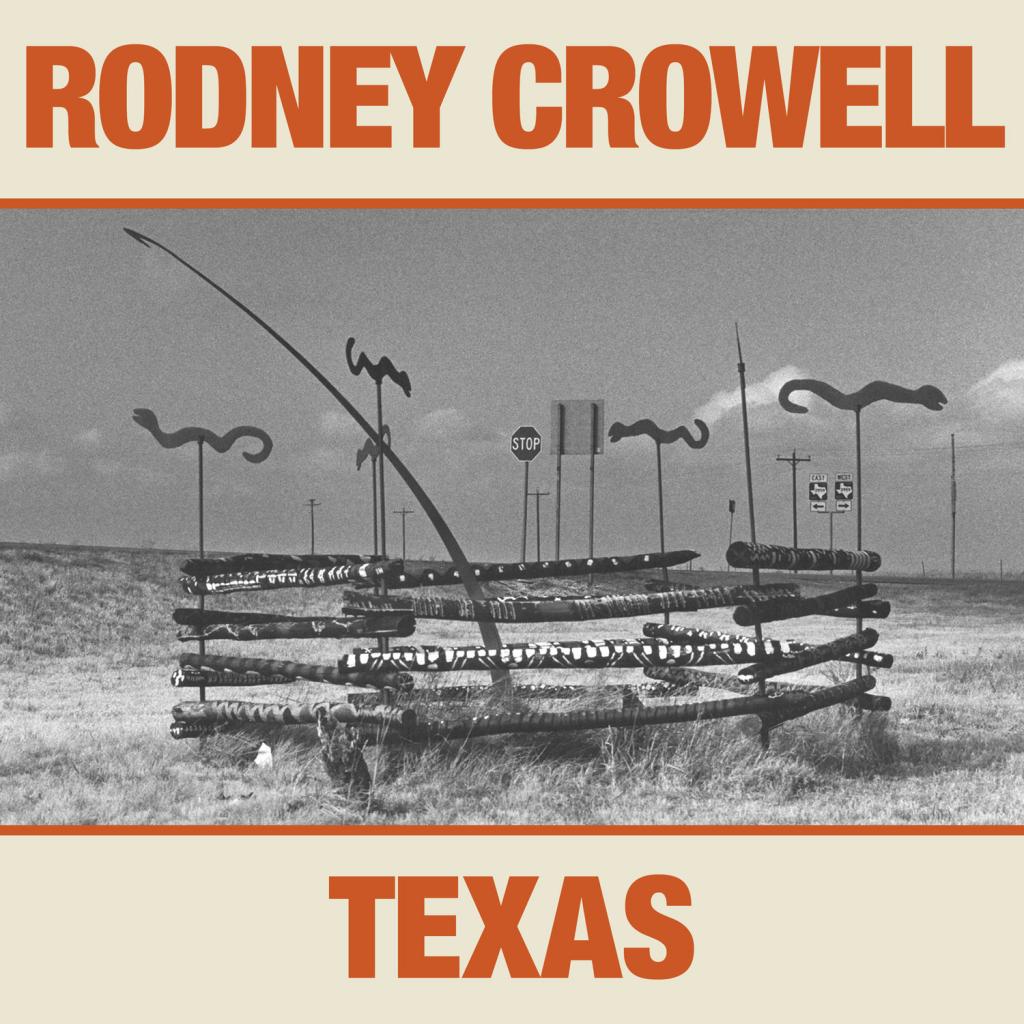

The Good, The Bad, and The Uncertain: Rodney Crowell’s Tribute to the Lone Star State

Since his 2001 masterpiece, The Houston Kid, and up to the revisiting of his back catalog on 2018’s Acoustic Classics, Rodney Crowell has faced his past not through rose-colored glasses, but with equal parts skepticism, cynicism, disdain, and sorrow. Even the explicit nostalgia of the autobiographical “Nashville, 1972” that closed 2017’s Close Ties hid a slight undercurrent of melancholy. However, on much of his latest album, simply called Texas, Crowell looks back not in anger nor with regret, but mostly with a big Texas-sized helping of dry, good-natured humor.

On paper, Texas reads like a major statement, and an army of A-list guests and top-tier musicians surrounded by a unifying theme all support that notion. In truth, its success comes down to Crowell’s own high standard of material and performance.

We’re introduced to Texas via “Flatland Hillbillies.” Co-written with author and occasional collaborator Mary Karr, “Hillbillies” stands as the album’s thesis statement. Randy Rogers and Lee Ann Womack join Crowell to celebrate an Irish-Cajun-Creole mixed family of johnboat shrimpers, oil rig workers, and pole dancers “gettin’ by on what (they) got” over Crowell’s lead guitar that evokes latter-day John Fogerty in full country-mode.

Vince Gill lends his inimitable high harmony to the JJ Cale groove of “Caw Caw Blues,” while fellow Houstonian Billy F. Gibbons gets to flaunt his harmonic-heavy guitar licks as well as his love of classic cars on the driving “56 Fury.”

On “Deep in the Heart of Uncertain Texas,” Crowell is joined by Texas natives Ronnie Dunn (Coleman), Lee Ann Womack (Jacksonville), and Willie Nelson (Abbott) as they waltz and reminisce about getting high on the lake and lost on the backroads. (Willie’s verse alone is the stuff of legend.)

The earliest track here, “Brown & Root, Brown & Root,” dates back to the mid-’70s and was covered by Steve Earle on his mid-’80s tours. Here, Crowell finally gives his take on it, trading vocals with Earle while the Dukes back them. After Earle offers a bit of background in a spoken word intro, the song takes a page from the Stanley Brothers as the tragedy of its story is offset by the traditional beauty of its melody; it’s one of the album’s best moments.

Also on the serious side is the timely tale of “The Border,” told from the perspective of a border patrol agent. What he witnesses and how he deals with his job when he returns home is a haunting, nuanced reminder of the power of perspective.

In what could be considered the singer’s conscience, Lyle Lovett asks “What You Gonna Do Now” as Crowell’s narrator drifts and grifts from one woman to the next until he finally meets his match and realizes he may not know the answer to the question the song’s title poses after all.

A jazzy cover of one of Guy Clark’s final songs, “I’ll Show Me,” emphasizes the sly nod and wink of the lyric while adding a bit more smoky ambience, while Ringo Starr (yes, that Ringo Starr, fresh from his work on Jenny Lewis’ On the Line) lays down a heavy midtempo groove for the straight-up rock of “You’re Only Happy When You’re Miserable.”

Another in a line of Crowell songs about natural disasters/bad weather (see “Storm Warning” from Close Ties and even the classic “California Earthquake” from his debut), “Texas Drought” sounds of a piece musically with his Orbisonian hit from 1992, “What Kind of Love.” It closes Texas firmly back where it began — in the Lone Star state, where, as he sings earlier on the album, he’s “tried hard to leave … but never did could.”