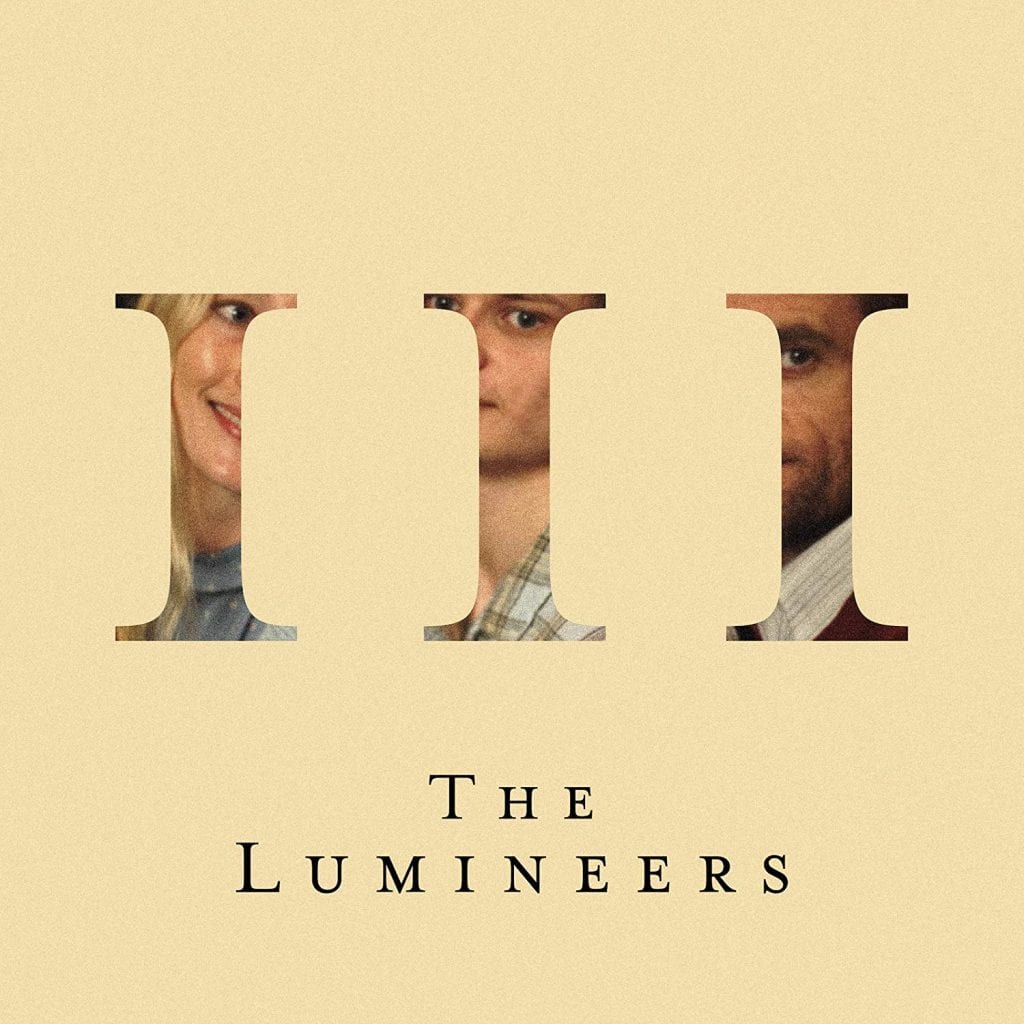

The Lumineers’ Austere and Elegant ‘III’

The Lumineers’ third album, aptly titled III, unwaveringly illustrates Wesley Schultz’s and Jeremiah Fraites’ gift for crafting anthemic tunes. The intro track, “Donna,” opens on a lo-fi note and sets an austere tone that persists throughout the project. The piano part brings to mind a child practicing scales in a large and empty room. A listener is immediately enrolled by Schultz’s voice, the track unfolding with a spontaneous and unrehearsed feel.

Melodically, “Gloria” is reminiscent of the title earworm from 2016’s Cleopatra. Lyrically, the piece delineates a self-destructive woman gripped by addictive impulses. Schultz’s tone is splashed with grief but also detached, an empathetic snapshot all the more effective for its avoidance of sentimentality or judgment (“Gloria, you crawled up on your cross / Gloria, you made us sit and watch”).

“Leader of the Landslide” demonstrates the duo’s talent for making maximal use of simple dynamics — a guitar and vocal intro, the addition of drums and piano mid-song, a melody with minimal variations buoyed by Schultz’s use of subtle vocal accents and tonal shifts.

Schultz’s lilt on “Left for Denver” reminded me of Blind Pilot’s Israel Nebeker circa the underrated 3 Rounds and a Sound. An intriguing intro — “What time was it when you were only 18 years old / You crossed the street, you crossed your legs / You came across a little cold” — quickly piques the attention, a broad-brushstroke song that vividly captures the passage of years within a three-minute frame.

“Jimmy Sparks” is the tour de force of the album and perhaps the most sophisticatedly crafted track in the Lumineers’ oeuvre, similar in terms of melodic scope and thematic complexity to such indie gems as Ryan Adams’ “Strawberry Wine” and Neutral Milk Hotel’s “Oh Comely.” The song addresses the life and travails of an inveterate gambler and his son, covering a 20-year timeline. The narrative view, a zoom-out rather than a zoom-in, conjures the stories from Joan Silber’s collection Fools, tales that paint “big pictures” while in no way sacrificing relatability or nuance.

The album closes with “Salt and the Sea,” a pristine melody coupled with Schultz’s visceral vocal delivery. Ulvang’s piano part is especially compelling, minimal accents bathed in reverb.

A contemplative and, in terms of color scheme, mostly black and white set, III’s understated elegance may elude contemporary ears. Then again, The Lumineers possess an uncanny affinity for the pop-folk hook, a skill that often seems to be effortlessly expressed. These guys are unquestionably songwriters’ songwriters, their compositional and performative approaches consistently engaging and worthy of study.