The Shopkeeper: Mark Hallman and Congress House Studio— A Film by Rain Perry

[This was originally written for and posted on Bob Segarini’s site, Don’t Believe a Word I Say. The plan was to write a piece for DBAWIS and a later one for No Depression, but as I read the original I struggled to find a better way to say what had already been written. Still, I think this documentary (The Shopkeeper) needs to be written about and reviewed on any number of sites relating to music and/or documentaries. So here it is, pretty much as it appeared in my column a few weeks ago.] Let us start:

You can file this one under “and I thought I knew something.” I just watched a documentary which starts “When I was a kid, music was everything,” a statement as acute to me as author Scott Turow‘s line “It suddenly hit me how much I missed music for which I once felt a yearning as keen as hunger.” It struck a note so deep in me that I watched all one-hour-and-thirty-one minutes feeling a kinship with the narrator (and, as it turns out, producer of the film), almost relieved that I was not alone.

For years, those of us who have been labeled eccentric if not practically insane for our love of music have suffered somewhat alone, though some of us found others to share our illness— years of alone time hiding behind headphones and stereo systems and speaking musicspeak consisting of lines from songs, facts, and opinions other people neither understood nor wanted to while isolating ourselves in a world every bit as fantastic as Dungeons and Dragons or Hobbitville. I lost three loves to that world, one lady complaining that I loved records more than I loved her, all stemming from my inability to walk past a record store without paying a visit. The first line of my biography should also be “when I was a kid, music was everything” for beyond the love I felt for my family and friends, it was.

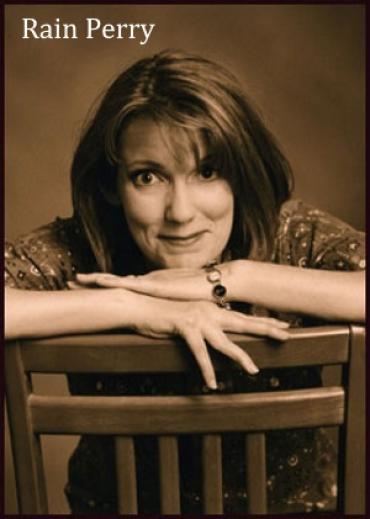

But this wasn’t me. This was someone who felt like me, loved music like me, but took it one step further. This was Rain Perry, who felt the urge to put her music on record, music which had developed to the point that it burst from her, three albums worth, and who, realizing finally that music had become a black hole when it came to money, deferred to film. Backed up against the wall, she wanted to tell a story and, looking around for a defined topic, decided that that story was not hers but that of the musicians she had recorded with and met at Congress House Studio in Austin, Texas. Mainly one musician:Mark Hallman. Hallman, you see, a seasoned musician and veteran of a plethora of bands by the time he came to Congress House, had taken in a mob of like-minded misfits over the years to record or to help record or just mix music for our ears. Well, not misfits, but people who fit there better than anywhere else maybe. Rain Perry was one.

Very early in the film, Perry states “I loved my producer, and I was not alone” before launching into a series of clips of others praising Hallman as more than human— or maybe human to the perfect degree— people like Eliza Gilkyson and Tom Russell and Sarah Hickman, who explained Hallman thusly: “I think, in his mind, you’re already perfect and beautiful and he just wants to color it a little bit.”

Ah, a love fest, I thought, and it didn’t bother me. That is pretty much what you get with superstars these days— musicians who knew one another only through brushes on the road of life now willing to recount “that day that her or she did this or that,” as if they were the best of friends. It is a template, I sometimes think, and hope that the next time I see a film on musicians, filmmakers do not toss in the star of today to make inane comments about how they were influenced, as if their music held water and would last. But right after a few musician comments, something happened and it turned out not to be a love fest at all. Not totally. Evidently all was not joy in mudville.

Perry immediately dives into an explanation of a Thomas Hardy poem, “The Convergence of the Twain, in which Hardy evidently explains a meaning of life in that while The Titanic was being built, the iceberg which would doom her was even then forming. Serendipity to the extreme.

The iceberg in this case is digital streaming. The Titanic, the music business. Wait.! What? Not more than a couple of minutes ago, I was watching musicians praise a studio owner/musician/engineer and now this?

All this before the credits. Less than four minutes. On a computer which is plugging away at turtles pace and is in consistent stop and go mode. Ten seconds at a time. Minimum ten second wait. It bothered me for a second, but soon I found myself eager for it to stop so I could think, put things in perspective, organize my thoughts. Perry had told me that the reason for making the film was in the film itself. And I had it. I thought. Oh, how delusional I was.

There are layers in this film I would not get until the end. True, it is about the shopkeeper, the aforementioned Mark Hallman, and it is about Rain Perry searching for answers. Turns out it is also about the music business and how it was and how it is morphing. It is about the musicians, on the whole a curious lot, trying to find their way through this jungle now being controlled by entrepreneurs and Wall-Streeters and wondering how their music is now co-opted by corporations which did not exist yesterday and yet are all-powerful today. How they are being forced to play a game they do not want to play and how some are pulling off the road for awhile to rest. Like Rain Perry, who for this moment has turned to film (she jokingly refers to The Shopkeeper as her fourth album).

Are you getting any of this? Do you even care? I ask because though you as a group are happy to accept music, you evidently no longer want to pay for it.

Right after the opening credits, I see Hallman in the studio seemingly laying down some slide guitar on a track, after which he says “I am extremely thankful that my doors are open, you know, and that’s big for me. That’s why I do the ritual. It symbolizes the good fortune that I have had, to be able to keep the people coming in and making music.” The ritual, it seems, is the sweeping of the welcome mats and the turning of the sign from closed to open. The ritual of the shopkeeper.

It’s no wonder people love this guy. At one point he says this— “Congress House is an instrument, basically. One big, beautiful instrument.” Not a word about himself as a producer or as a session man. A few words about his journey getting where he is (it all revolves around Navarro, a band in which he played and whose journey brought him to Boulder where things started to happen. You have to love the humility. You have to love his caring nature. He is the kind of guy you learn more from by hanging around and watching than from mentors who actually try to teach you.

Ever hear a musician named Trent Gentry? Neither had I, but after watching this documentary I am going to correct that. A simple overview of Trent recording voice back in 2014, unaccompanied, to a voice accompanied, to a vocal overdub by Stephanie Daulong, to the completed product stuns me. The process. The simplicity. The final result. It makes me gasp inwardly every time. I can’t help but think this is why we need studios. This is why we need producers and engineers and sidemen. It can be done in a bedroom or bathroom with decent results, yes, but to achieve what I just heard…

Carole King is part of this story, as is the aforementioned Russell, Hickman, and Gilkyson. So are Bradley Kopp, who has worked with Hallman for years, and Ani DiFranco, who I think would be a delight to interview or just be around, Iain Matthews, who ended up playing with Hallman in Hamilton Pool, and so many more. I would love to give details but that might spoil the journey and the journey is always the fun part of any good documentary.

I will tell you that Jon Dee Graham is part of it too and takes on the task of teaching us all what the hell happened when formats changed and, finally, digital distribution changed the whole psyche of purchasing (or not purchasing) music. Standing in front of graphics and charts, he pulls no tricks when calling out the industry for what it is— full of inequities. No bullshit. Four times he interrupts the flow to make points and make points he does.

Before I forget, here’s how I even got involved with this. I am mainly a music reviewer and few have ever approached me about documentaries or DVDs, but I got an email a few days ago from Ms. Perry. She had read a review I had written of Charlie Faye‘s album, Wilson St. and hoped I would be interested in looking at the film. The more we emailed, the more interested I became until she just sent me a link to the full documentary. I watched it all the way through yesterday. I am watching again as I type. Sometimes things are just meant to be, you know?

As for what musicians really think about Austin and the music business…

[When I wrote this for DBAWIS, I was remiss in not pointing out the contributions of Micah Van Hove. The cameraperson and editor have historically taken second place to producers, directors and actors. It is time to set things straight. Without the crack camera work on this film, it would not have the impact it does. I am sure that Rain Perry agrees with me when I state that much of the credit for this film belongs to him.]