In early 2017, I interviewed Tinariwen’s Abdallah Ag Alhousseyni for No Depression’s summer journal of that year. Donald Trump had just been inaugurated as the president of the United States, and I was asking international bands what kinds of issues they faced in entering and touring the United States. I was mainly asking about customs, as the new president had already made his xenophobic obsession with borders quite plain, but more general questions about traveling once inside the US were naturally part of these conversations.

Tinariwen, a Tuareg band from the Malian Sahara, had never had any issues with customs, Ag Alhousseyni told me through a translator, and once inside the US, the band’s experiences echoed those Billy Bragg and Ladysmith Black Mambazo mentioned separately: “We really enjoy touring in the US because the responses we get from the audiences are amazing,” Ag Alhousseyni said. “There’s always a good mix of people in the crowd — different ages, different social groups.”

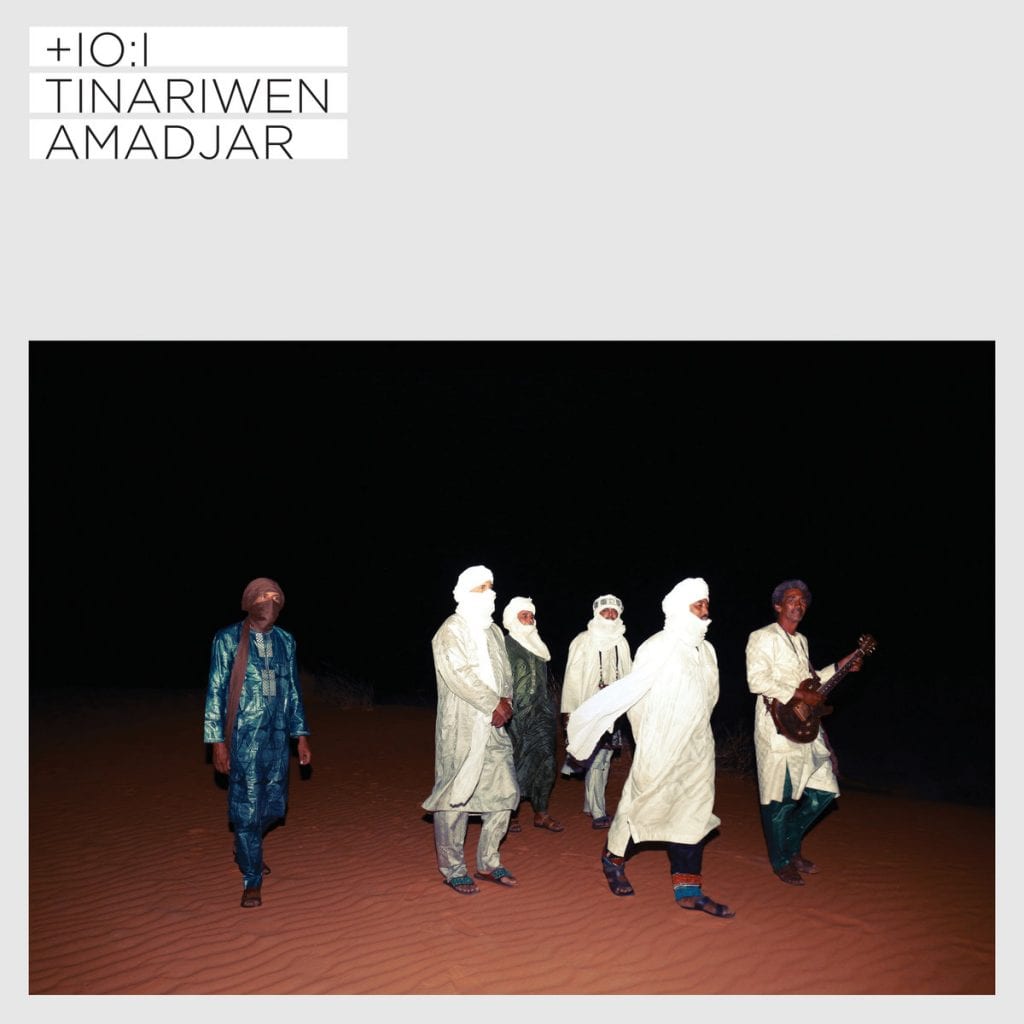

Yet in July of this year, Triad City Beat broke the story of a runaway Facebook thread, rich with threats of racial and religious violence, ahead of Tinariwen’s Sept. 17 date in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Based upon nothing but Tinariwen’s press photo, in which the band wears robes and turbans, commenters threatened to bring assault weapons for a “shootout at midnight.” In a bit of bleak irony, a band that only a few years ago found itself threatened by Islamic fundamentalists at home now found itself threatened by Christian fundamentalists on tour. But the show is going on, and Tinariwen’s new album, Amadjar, feels right on topic.

There’s a strong sense of place to Tinariwen’s music, and Amadjar communicates Tinariwen’s desert home with bittersweet poignancy. Sonically, Amadjar evokes the contemplative spaces of Tinariwen’s 2011 LP Tassili — an important similarity, as both were recorded in tents in the North African desert. (Amadjar’s immediate predecessor Elwan was recorded in Joshua Tree, which may explain the driving, agitated vibe and more electrified sonic landscape.)

Amadjar, the title of which means “the unknown traveler,” is comprised of songs about division, mortality, and loss of place in a world that is rapidly changing for the worse. There’s faith in the face of nihilism and there’s faith in a trusty mount. Guitars that ebb and flow and circular percussion establish the aural equivalent of road hypnosis while call-and-response vocals evoke not a band in a studio, but a circle of family and friends singing of a nomadic life in a troubled world.

As author Mohsin Hamid wrote in August’s National Geographic — the human migration issue — “none of us is a native of the place we call home.” This meditation on transience could ring true for a band whose home is a sprawling desert, whose tempos match the patient plod of dromedaries crossing its expanse, and for whom motion is the only constant.

Album opener “Tenere Maloulat” introduces themes that are explored throughout Amadjar. Tinariwen’s members are tired of fighting, tired of divisions, and some tunes toe the line of existential exhaustion. “I have no hate left for anyone. My soul is confused,” Ibrahim Ag Alhabib sings on “Tenere Maloulat,” a low-tempo dirge evocative of 2014’s Emmaar. (For the purposes of this review, we’re using Andy Morgan’s English translation of the original Tamasheq lyrics, courtesy of Anti- Records.) “I believe in no one now / I’ve become the son of gazelles who grew up in the meanderings of the desert.”

It’s followed by the insistent, patient drive of “Zawal,” featuring tasteful violin courtesy of Nick Cave sideman Warren Ellis. This cut’s apocalyptic lyrics describe the rapid approach of a storm that could be read as a metaphor for climate change, sociopolitical instability, conflict, or Western interference. The patient, meditative Amadjar is less of an electric guitar record than its predecessor, the scorching Elwan, though the deceptively placid “Mhadjar Yassouf Idjan” is an exception. On the haunted, transcendentally melancholy “Iklam Dglour,” Ag Alhabib contemplates mortality, though his bandmates’ harmonies suggest he doesn’t do so alone.

“Even when they’re put together / the Arabs and the Tuareg of Timbuktu, Gao, Kidal, and Tessalit are in a minority / my friend, I beg of you, let’s speak with one voice,” several members sing in unison on “Takount.” “These last few years, I’ve journeyed without my saddle / No one even offers me a meal anymore / I’m threatened.” The song rolls and sways with Tinariwen’s distinctive Sahara blues tempo, while acoustic instrumentation and hand drums give it a small, intimate feel. This is the song of an endangered people, yet — and as Hamid wrote in National Geographic and in his essential novel Exit West — one of the most human things one can do when faced with danger is to go, whether by foot, horse, boat, car, plane, or dromedary, to a place where survival is possible.

“Ours is a migratory species,” Hamid wrote in National Geographic. “Humans have always moved.”