Frank Kimbrough – Monk’s Dreams: The Complete Compositions of Thelonious Sphere Monk (Sunnyside) (6-disc-set) *

I happened to meet pianist Frank Kimbrough last February, after a concert in Illinois by the Maria Schneider Orchestra, for which he plays piano. Affable and approachable, he chatted with me a bit and, learning I came down from Wisconsin, he mentioned that his quartet would be playing soon in Stevens Point.

But recently, when the truly astonishing accomplishment of Kimbrough’s Monk’s Dreams: The Complete Compositions of Thelonious Sphere Monk was released, I was a bit stunned to think back to our conversation.

At the time, Kimbrough was surely in the midst of extensive research and preparation for this ambitious project, which he would be go into the studio with his quartet to record only a few months later, in May. He never mentioned a word about the Monk project to me, knowing that I’m a jazz journalist. How to explain it?

Pianist Frank Kimbrough Courtesy step tempest

Perhaps it's an instance of what the box set’s annotator Nate Chinen calls Kimbrough's "curatorial humility." It's a key to the mindset and attitude that he brought to a project whose presumptions might greatly risk the pitfall of excessive hubris.

In Chinen's notes, Kimbrough explains: “There is something that I tell all my students: the composition is a gift from the composer, for how you're going to improvise on this tune. It gives you information. It gives you motive. Gives you intervals… rhythms…all sorts of things to deal with. And if you just throw all that out the window with the first chorus of your solo – to play a bunch patterns you figured out in a book, or something that's just going to get applause – then I think you're doing a disservice to the tune and to its composure."

Kimbrough's multi-instrumentalist horn player Scott Robinson explains how their smart humility in the light of Monk music guided them: “When you listen to Monk play his music, he never strayed very far from little twists and turns and funny little mechanisms and structures that recur through the form. They run all through his solos, pretty much all the time."

The result: Kimbrough and company have carved out the most authoritative and delightful reclamations of jazz history in recent memory. A profusion of groups have covered Monk material in recent years, especially since he died in 1982, an event which Kimbrough says began his long journey to this pinnacle achievement, modestly as he thinks of it.

Robinson’s superb brass & reed versatility is key, and over the course of these six CDs he clearly asserts himself as among the most gifted of the quite rare musicians who've mastered both the valve brass instruments and reed instruments, probably the best such since the late Ira Sullivan.

As for Kimbrough, self-described as an “impressionistic” pianist (as evident with his superlative work with Schneider), he has a profound understanding of complex harmony and Monk's not-infrequent bi-tonality in his voicings. Kimbrough's also worked with the spare but ultra-sophisticated and cool Monk contemporary Lee Konitz. So he can strip away the gauze and inhabit Monk’s “high priest of bop” posture like a re-imagined second coming. Monk once said, “It’s sometimes to your advantage for people to think you’re crazy.” Advantage Monk. Crazy like a genius. His “dreams” are goofball-cool, cubist yet often danceable, slide-off-the-page poetry and, amazingly, this set encompasses the entire Thelonious Sphere.

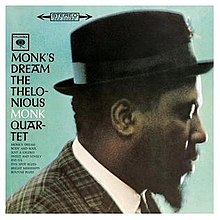

"Monk's Dream," the Thelonious Monk album that inspired the title for the Kimbrough project. Courtesy Pop matters

Among the historical revelations are a healthy handful of tunes Monk never recorded or, if so, very obscurely. For example “Two Timer” (ever heard of it?) plays out as a disarmingly enchanting yet terse melody. As usual, Monk’s uncanny and quirky arranging of resonant, wide intervals give the tune its vibrance, which allows for fine solo takeoffs.

These qualities, Monk’s almost unerring tunefulness and sly, sometimes slapstick rhythmic wit, and the music's frequent friendliness, make his to this day perhaps the most accessible style to uninitiated jazz listeners, among the giants of bebop. And yet the music, sounding so fresh here, invariably rewards frequent revisiting and close listening, which is a significant reason to consider this set, no matter how much recorded Monk you own.

Monk music clearly brings out the comic sensibility in many interpreters, though they must be mindful to not “play at” Monk’s music and to guard against pushing it into caricature, both things which too many musicians do, Kimbrough notes. Such slips rarely ever happen here.

The utter relaxation and assurance of the quartet’s playing throughout suggests how they’ve made the music their own and learned well what Monk always counseled his band members: “Play yourself!” Don’t try to play like, or at, Monk, a fine line sometimes.

These four men, the great bassist Rufus Reid and drummer Billy Drummond, convey all the authenticity of dedicated Monk fellow travelers who clearly love the Monk "thunk" -- the crystallized genius of his percussive pianistic attack, which reflects the bracing vitality of his music. Monk was fearless at the keyboard. As he once declared: "There ain't no wrong notes on the piano!"

It’s a reason, too, that the drummer needs a liberated feel for Monk’s extreme rhythmic limberness, almost physical comedy and contorted grace. Drummond covers all that like a master gymnast.

One of the first signs of this band’s small strokes of personalized genius arises on the second tune, “Light Blue,” one of Monk’s most catchy and expansive melodies, but usually played in a jaunty medium tempo. This quartet stretches out their reading of the theme into languorous, exquisite phrasing. Then they allow bassist Reid the first solo, an atypical sequencing, yet he perfectly extends this oddly stately feeling.

Then Kimbrough’s piano enters and unfurls itself tripsy-dipsy, chock full of mirthful phrasing. Robinson, switching from trumpet to saxophone a few times in the tune, has an air of vaguely “above it all,” like a guy with three martinis in him. Yet he does just what he wants to do, to make this stuff alive, and his own. The “Light Blue” theme returns at the end, now a bit soggy but gloriously right, even as it might be conventionally “wrong.”

“Ba-Lu Bolivar Ba-Lues Are" displays Monk’s offbeat wit even in its title, and the band turns this ba-lues into the woozy blooze that it should be.

“Little Rootie Tootie” is played by Robinson on a gutturally songful bass saxophone, an absurdly delightful evocation, here of a ponderous monstrosity recalling fondly a small child called “Little Rootie Tootie” – Monk’s affectionate nickname for his first-born son, now the noted musician, T.S. Monk.

And yet the tune greatly suggests Monk’s humanity and, for sure, this project is hardly a long exercise of broad strokes. Nuance arises in the most unlikely places and in some of the most appropriate. Robinson opens the ballad, “Ask Me Now" with unaccompanied tenor sax, tentatively, pensively and romantically, as does the ensemble’s ensuing tender entrance, all apt to the title’s delicate implications of timing. What a welcome seduction.

Robinson's versatility is key to the variety the band achieves in compiling all of the music of a single composer, “genius of modern music” that he was. Besides echo cornet (a cornet with a fourth valve and a detachable second bell), Robinson plays tenor and bass saxophone, and bass clarinet. He also displays his mastery of something called the contrabass sarrusophone, a sort of hybrid of a contrabass saxophone and a bassoon. All the low horns provide plenty of moments of gentle and jocular humor, hard swing and and surprising lyricism.

Valve brass and reed instrument master Scott Robinson playing his bass saxophone, among the wide dynamic range of instruments he plays throughout "Monk's Dreams." Courtesy Luna Stage.

Amid those precious qualities, if you join this group on this journey you will enter into many of Monk’s fascinating, weird and vivid musical dreams. It's a place you may come to hold as special in your life, a place you’ll likely return to, again and again, for refuge from this often-difficult and ugly thing called life. Monk had a holistic cure for that, even distilled in a single tune title, “Ugly Beauty.”

____________

* See my previous ND post, where I chose Monk's Dreams as jazz album of the year, along with my top ten best jazz albums of 2018.

Comments ()