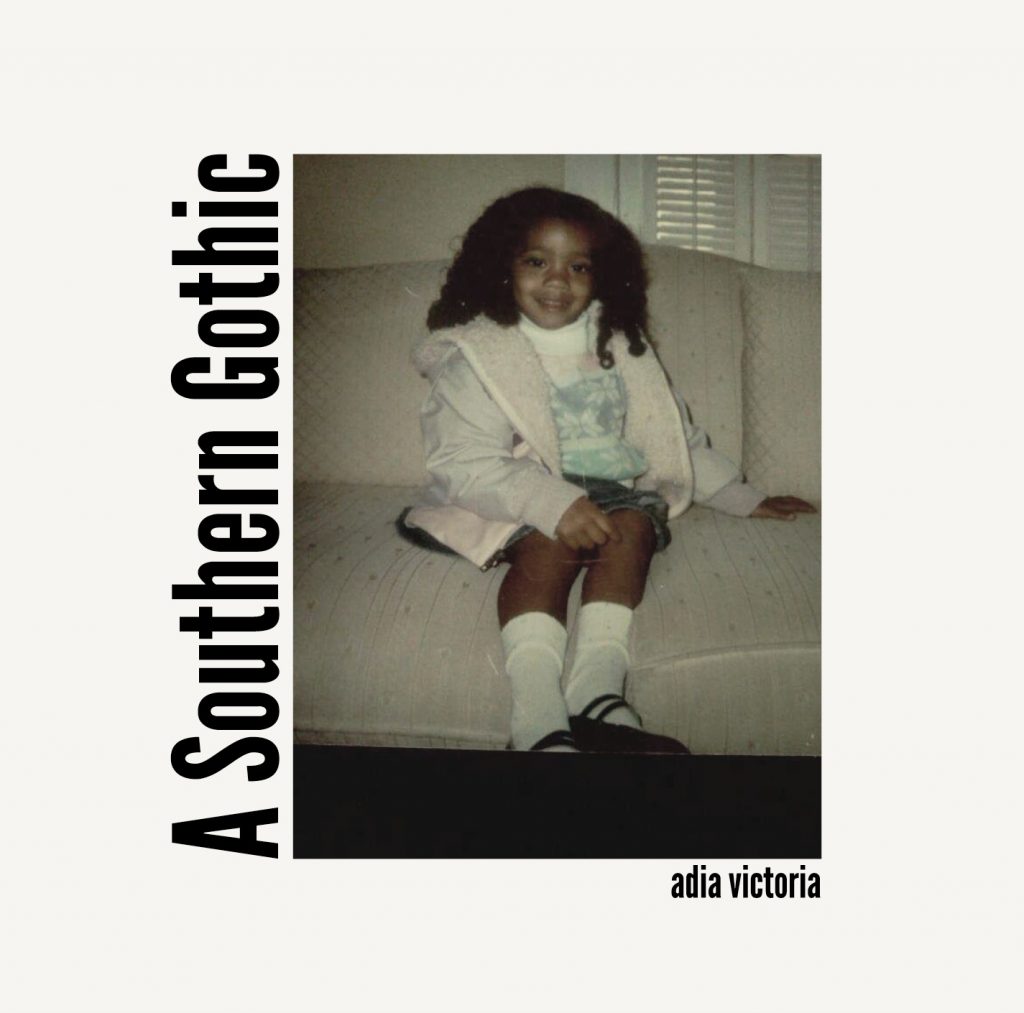

With ‘A Southern Gothic,’ Adia Victoria Tells Her Own Story of the South

The phrase “Southern Gothic” brings to mind moss-draped drives to plantations, grotesque scenes peopled by mean-spirited men or by sideshow freaks, and haunted woods and houses with the skeletons of slavery filling the closets. In his novel Absalom, Absalom!, William Faulkner has one of his characters ask another to “Tell about the South. What’s it like there. What do they do there. Why do they live there. Why do they live at all.” Faulkner’s stories tell about only one South, though, the South of the white male, and Black men and women play, at best, marginal roles, the characters standing in for cultural stereotypes. Adia Victoria’s new album, A Southern Gothic, tells a different story about the South.

“Magnolia Blues,” which launches the album, repeats a simple musical pattern that lays bare one of the very images that perpetuates the myths of the Old South. The limbs of the tree and its shiny leaves hide the egregious evils of the region, just as the sweet-smelling flowers create a scent that covers the odiferous acts of racism of this South. Victoria reclaims the magnolia for Black women — “I’m gonna plant myself under a magnolia / I’m gonna let that dirt do its work.”

Victoria’s smoky jazz vocals ride over pattering jazz blues in “Mean Hearted Woman,” which palpably conveys the shift from love and desire to vengeance: “After all the pain you out me through / You better hope I don’t catch up with you.” Kyshona Armstrong’s soaring vocals kick off the viscerally piercing “You Was Born to Die” — punctuated by Jason Isbell’s screaming slide on the instrumental bridge — evoking the insidious claustrophobia of a relationship marred by abuse which, as the lyrics make clear, became the destiny of the song’s main character from the moment of her birth.

The minor chord folk ballad “The Whole World Knows” depicts the conflict between the spiritual and the earthly, a young girl whose preacher father has already lost control over his daughter’s life by the time she’s three, while the rhythmically swaying “Far from Dixie” evokes the insidious nature of the South: “My blood is yours and yours is mine / I got you in my bones no matter where I roam.”

With a fiery brilliance, A Southern Gothic subverts the title phrase. Victoria tells about the South from the perspective of Black women in a collection of mesmerizing songs that traverse the rawness of Hill Country blues, the country soul of Memphis, the urban rap of Atlanta, the spiraling layers of folk blues, and the sultry languor of smoky jazz. The songs unfold with a brutal intimacy and a steely energy that tells about Victoria’s own South and the deliberate acts of injustice and unconcealed terrors that characterize the too-often accepted story of the South foisted upon history by white men.