Beyond an angel’s art:

Bob Dylan’s voice, his vocal styles, delivery, and the oral tradition of storytelling through song.

In August of 2017, ISIS magazine published an article by Tara Zuk, discussing Bob Dylan’s voice.

Reference:

Zuk, Tara. “Beyond an angel’s art: Bob Dylan’s voice, his vocal styles, delivery, and the oral tradition of storytelling through song.” ISIS 193, August, 2017: 37-48

“And until then what you got to lose but the losing? We’re fallen angels who didn’t believe that nothing means nothing.”

Jack Kerouac, Book of Blues

It becomes a regular occurrence if you are a Bob Dylan fan. Well-meaning friends tolerating your interest will nod distractedly at your discussion of the latest tour or album and tell you that although Bob Dylan is a fantastic songwriter, they prefer his songs performed by other people (Adele, Guns N’ Roses, Billy Joel, Jimi Hendrix). Or they will tell you that although they love the lyrics, Dylan sounds whiny and nasally, he mumbles too much, and they can’t listen. Some may even accompany their statements with what they believe to be a humorously Dylanesque impersonation, wheezing their way through a line or two of ‘Blowin’ In The Wind’ like a parody of a bad parody twice removed, laughing at their own cleverness as though no one had ever heard the joke before.

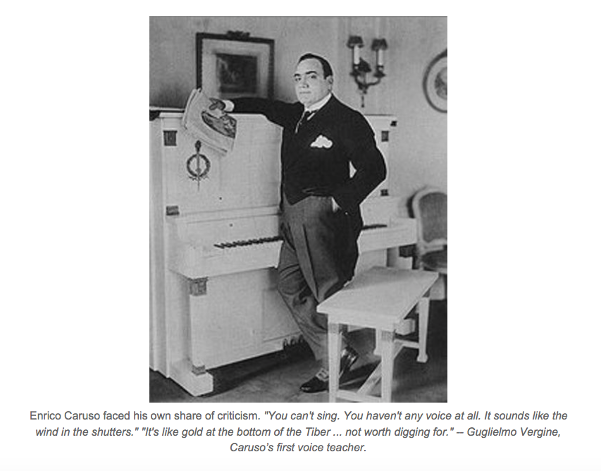

Well, we have heard it all before, and not just from the armchair critics.

Following the release of the album Tempest in 2012, an article from Max Thorn on the website Vulture collated a few of the more interesting descriptive phrases used by reviewers to describe Bob Dylan’s voice. (1)

Jon Pareles of the New York Times talks about Bob Dylan’s voice being “the wry cackle of a codger who still has an eye for the ladies. […] a raspy, phlegmy bark that’s not exactly melodic and by no means welcoming.” (2) Sean Daly in the Tampa Bay Times called Dylan’s voice a “zombie bullfrog holler” (3) and Alexis Petridis in The Guardian describes “a terrifying, incomprehensible growl that sounds like one of those death-metal vocalists in full flight.” (4)

And this is not a new phenomenon. David Bowie once affectionately but tellingly compared Bob Dylan’s voice to “sand and glue” in his Song For Bob Dylan (5), while John Updike scathingly described Dylan as having a “voice to scour a skillet with.” In April of 1965, Fred Billany described Dylan’s voice as having a ‘dry and bitter quality’ (6) and Time magazine in 1963 spoke of his ‘whooping harmonica, skinny little voice’ which at its very best ‘sounds as though it were drifting over the walls of a tuberculosis sanitarium’ softening with, ‘but that’s part of the charm.’ (7)

People since day one have been trying to tell us that Bob Dylan can’t sing. The truth is, he is one of the greatest singers we have ever known, a communicator of melody and lyrics in the best oral tradition, and someone who can use his voice to transcend the borders of time and place.

The ‘poetics of the voice’

“I’m just as good a singer as Caruso.

Have you heard me sing?

Have you ever heard me sing?

I happen to be just as good as him… a good singer, have to listen closely.”

Bob Dylan (8)

Literary writing by necessity is ‘mute’. A facsimile of voice is present on the page, but it is little more than a shadow. Writers use devices, style and technique to evoke the concepts of voice and orality. However, that voice alters from reader to reader. A writer can never be sure that their readers hear the voice they intended to transmit. That is part of the joy, and also part of the frustration.

As Christophe Lebold argues in his essay A Face like a Mask and a Voice that Croaks: An Integrated Poetics of Bob Dylan’s Voice, Personae,and Lyrics (9), Bob Dylan is in an interesting position. A literary study of his lyrics shows that when read on paper, Dylan’s songs have elements of what Lebold calls ‘high poetry’. Formal poetic structures and devices are evident and are often executed with skill and precision. However, the lyrics are fused with the oral tradition and the use of voice in a way that simultaneously elevates Dylan’s music from the realms of popular song, whilst also giving his verses the orality, the concrete voice, which is lacking in the written words alone. The songs then become a form of oral literature.

Therefore, to study Bob Dylan’s lyrics without also studying his voice and the way he uses it, is to miss a vital part of his performance art.

Poetry and music share common ground, and in Bob Dylan’s songs they are inseparable. Excellent studies of the lyrics exist to prove to the world the depth of style, symbolism, and literary techniques employed by Dylan. However, it takes a performance of the songs to lend them their true voice and brilliance.

As mentioned by Declan Lynch (10), Bob Dylan has faced several decades of misunderstanding. His lyrics are poetic, but they are not just poetry. Dylan’s music depends heavily on his vocal performance and delivery for them to achieve their full and most powerful complexities; just as the writer of a drama requires actors to deliver the lines and make the words come alive. To reduce Dylan’s songs to the category of ‘pop music’ or take the lyrics alone on paper and place them in the category of ‘poetry’ is to do him a disservice. Because without the voice and the music, the lyrics are incomplete. A vitality is lost.

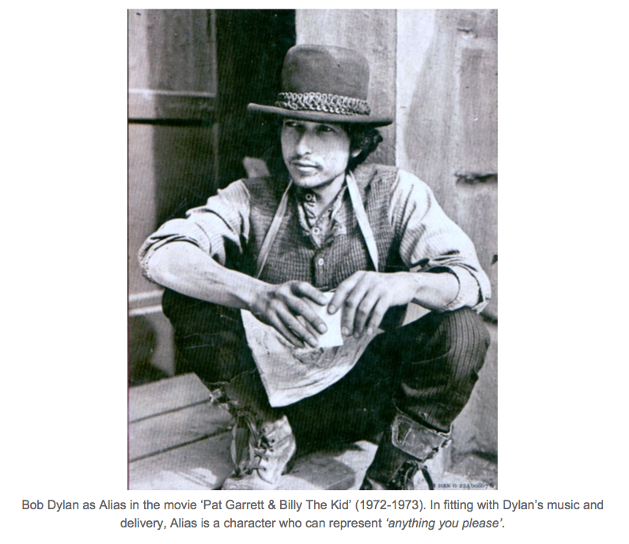

Bob Dylan has an idiosyncratic vocal style that expresses the emotion of a piece of music quite effectively. His voice conveys tone, rhythm and cadence, intonation, age and a subtlety of expression that within seconds can create a persona which is so tangible it can almost be perceived as semi-autobiographical. A whole other topic for discussion is the concept of Bob Dylan’s use of masks; je est un autre (11). We can surely say that Bob Dylan’s voice is yet another mask. If each song has a ‘voice’ and an orality – a protagonist whose desires, fears, imperfections and strengths need to be immediately communicated to the listener – the best and most successful method to convey each story is through the voice. Wearing and replacing different vocal masks is a powerful way to express the underlying message, viewpoint and feeling of a song.

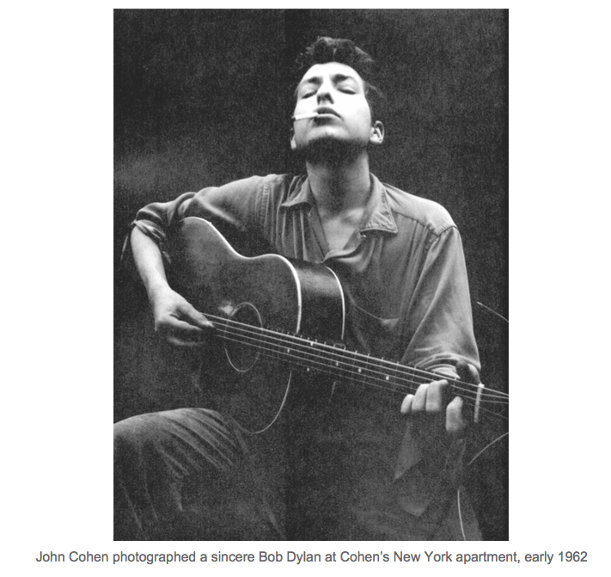

You told me that you’d be sincere

“Sincerity is everything. If you can fake that, you’ve got it made.” George Burns (12)

In the development of the recorded popular song through the twentieth century, there was a gradual shift away from long instrumental dance pieces with short vocals as a hookline (swing, jazz and early popular romance songs), to the point where the voice became dominant and punctuated by shorter instrumentals. This was partly to do with the development of microphone technology making the voice more audible above the sound of large bands and orchestras. But also, as the music industry became geared towards charts and sales and market dominance, audiences responded more directly to the human voice than to instrumentals, especially in the short format of a pop song for radio broadcast which went hand in hand with the creation of singing celebrities, heartthrobs for the affluent youth market. This was a contrast to the live venue music that had previously predominated when recording was a more secondary feature. (13)

The natural human perception is that we immediately equate ‘voice’ with a sense of another person’s self. Linguistically, voice and identity (individual, social and cultural) are intrinsically linked. Your voice is as exclusive as a fingerprint – it reflects your gender, age, culture, origin, education level, current state of mind or emotion, and even personality traits. Therefore, a singer who is able to flexibly control and alter elements of their voice to transcend such boundaries, is going to be a more successful communicator of a variety of characters, situations and emotions. The flexible singer can sing convincingly from many different perspectives. This process can become contrived and lack a feeling of authenticity when used as manipulation for effect. It is most successful when employed as a natural reaction to the music, and is often combined with a sense of vocal vulnerability. (14)

The crack and the croak. Holding a note a fraction too long. A stumbled lyric. Words crammed into a line, challenging the rhythm and balance. These techniques all convey specific flaws or imperfections to fit the limitations and struggles faced by the protagonist.

Vulnerability and fallibility is human – and it is the human experience that binds us and authentically connects us. For a singer, that connection is made through the voice.

Some singers sing at their audience. They may be pitch perfect, pretty and smooth, but sometimes this comes across as lacking an element of authenticity. They are singers for whom each song sounds similar so as to always maintain the one persona, the persona that works, safe in the knowledge that sometimes the commercial public tends to like the comfort of predictability and art that does not unduly challenge expectations.

Then there are the singers who sing to their listeners, connect with them and draw them in with apparent sincerity and genuineness, challenging perceptions and almost daring you not to react. This is how Bob Dylan is able to convincingly engage an audience – from the perspective of a woman, an old transient bluesman, a Dust Bowl refugee, a Nashville country music crooner, a gospel singer, a minstrel, a troubadour, a vaudevillian, a sharecropper, a British folk balladeer, an Irish sailor, or a soldier from the American civil war, a prisoner – each perspective given a backbone of truth and believability directly through the use of voice and phrasing. Each one believable because of the perceived sincerity in Dylan’s voice, and the honesty of his delivery.

In a 2011 interview for Rolling Stone magazine, Paul Simon said of Bob Dylan:

“One of my deficiencies is my voice sounds sincere. I’ve tried to sound ironic. I don’t. I can’t. Dylan, everything he sings has two meanings. He’s telling you the truth and making fun of you at the same time. I sound sincere every time.” (15)

However, this difference between the two artists might be looked at in another light. Whether Paul Simon finds it difficult to express irony is not for debate here, but I believe that Simon is correct – Dylan certainly has the ability to convey multiple meanings through a combination of lyric ambiguity and vocal delivery. Indeed, Bob Dylan’s ability to tell you the truth and make fun of you at the same time is an essential aspect of his act. However, this does not make him any less sincere than Paul Simon. The ability to convey irony, ridicule, or multi-faceted layers of meaning does not reduce authenticity or sincerity. The human condition is complex. It is natural for a person to feel a combination of emotions simultaneously. A failed relationship, for example, may result in feelings of anger, regret and sadness.

For instance, in Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right we can read the lyrics:

I’m a-thinkin’ and a-wond’rin’ as I’m walkin’ down the road

I once loved a woman, a child I’m told

I give her my heart but she wanted my soul

But don’t think twice, it’s all right. (16)

On the paper, we are faced with ambiguity. Is this an expression of resentment? He gave her all he could, but she wanted more, she wanted the impossible. It obviously is not ‘all right’ and the irony in the line can express a level of bitterness that the experience ‘wasted his precious time’. Or is this a song of sadness and regret? The singer is so sorry that he couldn’t give her what she needed, but everything will be all right. The ambiguity and irony is still very much an expression of honesty and sincerity. And the only way we can interpret the words for ourselves (not definitively, for they are organic and changing) is to listen to the voice and delivery as Bob Dylan sings them, and react to that stimulus. And Dylan surely knows full well that the way a person will react to any song will depend not even solely on his delivery, voice and persona, but the listener’s own state of mind.

Prosody and connection

“People think they know me from my songs. But my repertoire of songs is so wide-ranging that you’d have to be a madman to figure out the characteristics of the person who wrote all those songs.”

Bob Dylan (17)

Prosody is the pattern of rhythm and sound used in poetry and voice – the musicality of speech and language, the patterns of stress and intonation. Those patterns are processed by the right temporal cortex of the human brain from the age of approximately 7 months, and whilst they may elicit varying responses from a listener, the meanings of the patterns are universally identifiable. That is the reason why we can tell, without speaking a language, whether someone is angry, happy, sad, or bored by their tone of voice. (18)

The prosody of a person’s language and intonation are significant in communicating their emotions and attitudes, making connections with others or creating divisions. Think of how the tone of voice, the rhythm, the stress, the emphasis, changes between a politician making a public speech or talking in an informal interview… or even how they must talk at home to their family. Think of a teacher adapting their voice when they enter a classroom of uninterested adolescent students.

Considering the main linguistic attributes of prosody (19), we can see that in all areas Bob Dylan is individual and often displays a difference from other singers. If we just look at the auditory, non-acoustic terms, we can immediately tell that Bob Dylan communicates his song by altering his pitch, the length of the word sounds (often quite differently to the conventional pronunciations and syllable emphasis), and utilising the pause to separate phrases, phrasemes, and constituents.

In his essay A Foreign Sound to Your Ear: Bob Dylan Performs “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009, Steven Rings makes the following assertion in his introduction:

Bob Dylan is no stranger to academia, but he has yet to gain the full attention of music scholars. There are likely many reasons for this neglect, one of which is the tendency to elevate the literary Dylan above the musical one; another is the surprisingly durable tradition in music theory and (to a lesser extent) musicology of valuing complexity in harmony, melody, rhythm, and form—areas in which Dylan’s music is often (though not always accurately) perceived as simple. (20)

It is my suggestion that Bob Dylan’s musicality very much integrates his vocal and linguistic prosody, which creates intense connections with some fans, whilst simultaneously pushing other listeners away. Almost all fans will have a song or two that they consider to have been a ‘mistake’, whilst those same songs have many ardent followers. It should also be mentioned that the complaints of some of Dylan’s detractors often centre around the inability to understand and make out precise words when he sings. However, that is like life, when listening to others speak in conversation. Much as when Hitchcock made his first partial sound film Blackmail , he often recorded people speaking but undecipherable, as he assumed films would be like that. Years later some film makers went back to indecipherable dialogue in parts. But after Blackmail everyone aimed to get the technology to precisely give words. (21)

Deceptively simple melodies (that are often not at all ‘simple’, as some people who have attempted to perform them can attest) are vocally embellished and enhanced by nuanced phrasing, pauses, and the challenge of lines where the vocal syllables appear to overload the musical beats.

Listening comprehension, and processing the use of context and prosody to derive meaning, is very much linked to general reading and language comprehension skills and tastes. Sometimes a reader has prefered styles and authors, connecting with and understanding certain writers whilst having no bond to others. In a similar way, listeners will have prefered speakers and singers. These reactions are often subconscious and can be due to preference of accent, rhythms of speech and choice of vocabulary. It can also be linked to the ability to process, or the preferences for / against, phonological modifications such as assimilation, elision, sandhi, and intrusion. (22)

Some listeners feel uncomfortable when they are unable to decipher the prosody – when the rhythm and emphasis on words creates ambiguity and uncertain definition, it discomforts them. (23) They may enjoy the same song performed by a different singer, simply because they are more comfortable with the delivery and emphasis of the performer.

I’m just average, common too

I’m just like him, the same as you (24)

Bob Dylan’s voice has an amazing quality of ‘nowness’ to it. With its timeless everyman character of slight imperfection masking the breathtaking depth and brilliance, the genius of both the lyric construction and the vocal prosody. His voice has the ability to take a song from any era and construct it in a way that is relevant and enduring – an intriguing mix of immutable human truths and ephemeral characters in unspecified times.

But it is exactly the conversational tone and rhythm, and the deceptively simple style, never overblown, that connects immediately with listeners. It convinces many people that he is talking to them personally, that he is talking about their lives, that he understands them, and that they in turn know him. He’s everybody’s brother and son.

The wolf pit of Dylan’s vocal delivery has the branch-covered veneer of simplicity and ease and connectivity, the tempting carrion of a good musical hook and a stylish attitude of cool. It is only as you plunge through the surface you realise the hidden depths, and before you can jump back you’re freefalling into the shadows, astounded by the multiple layers that went into the construction.

Sometimes, the silence can feel like thunder…

“Out, out, brief candle! Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player That struts and frets his hour upon the stage And then is heard no more. It is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury Signifying nothing.”

Macbeth Act 5, scene 5

William Shakespeare (25)

Until we have the gift of silence, we can never truly understand the power of sound.

Silence is tangible. The pause can indeed be pregnant – swollen, heavy, and full with the promise of a new birth of ideas and feelings. Effective use of vocalisation includes knowing when not to vocalise. Just as in interviews, Bob Dylan always uses silences to effect, a habit of taking long pauses between his differently cadenced responses depending upon his level of interest. A chance to think. An uncomfortable pause after an inappropriate question. An opportunity to make the questioner feel uncomfortable. A reason to declare the meeting over and leave.

In life as in the songs, the very absence of sound has its own meanings. And Bob Dylan often uses silence to great effect in his songs.

Firstly, consider the staccato phrasing on The Man in the Long Black Coat . Each line broken and half-whispered so that the anticipation builds in an atmospheric way that makes the breaks and pauses as important as the lyrics themselves. The events and thoughts are disjointed and the conclusion of the song – the mysterious disappearance remains without ‘closure’ or answer – is highlighted by the choppy delivery. The only moment of any fluidity is the soaring wave of the bridge which rises ( ‘There are no mistakes in life, some people say’ ) is broken by an aside ( ‘And it’s true sometimes, you can see it that way’ ) then rises a second time ( ‘People don’t live or die, people just float’ ) only to be broken yet again ( ‘She went with the man in the long black coat’ ). We can see how the listener gains meaning and intent from the phrasing and prosody.

There is an example in the song Highlands when a delicious (but maybe unintended?) pun is expertly worked by a silence:

‘Insanity is smashing [pause]

up against my soul

You can say I was on anything [pause] but a roll’ (27)

The thought of insanity being ‘smashing’, in the UK sense of being fun and pleasant, enters the English listener’s head for that split second before the full meaning of the continued line takes grip. Then there is the inference created by the second pause. We may fleetingly wonder, what is the singer on? Is this a drug reference? Then the completion after the pause shows us the meaning.

In The Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar there is a great line with an intriguing use of the pause:

‘There’s a wall between you [pause]

what you want and you got to leap it

Tonight you’ve got the power to take it

Tomorrow you won’t have the power to keep it’ (28)

The written lyrics add the word ‘and’ in that pause (29) (in some performances he sings the ‘and’), but on the released album recording he does not sing it. He pauses. The silence becomes as physical and as insurmountable as the metaphorical wall he talks of. In the frenzy of that fevered song, it is a stroke of masterful vocalization that sets Dylan apart. He is never obvious. Always subtle. But therein lies the intensity that obviousness is devoid of.

As you listen to Dylan’s music, you will find countless examples of the same thing. Never sloppy. Always precise. Carefully measured.

It also marks a level of confidence and bravery. Silence can be terrifying. We have all known times when we have filled the air with words out of insecurity or nervousness. Anything to fill that chasm, that moment of empty nothingness.

“Experience teaches us that silence terrifies people the most.” (30)

However, there is value to silence. It is the eye of the storm which sometimes has more to say than any word could express. Or it can be an unspoken thought which hits harder than any shouted expletive.

This is true in life as well. There are moments when silence says more than words ever could. There is a time for quiet, for reflection, for listening and contemplation.

I began this section with a quotation from Macbeth which describes life as ‘ a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing ’. Transferring this idea to Bob Dylan’s music, using an understated pause correctly can speak volumes and can only be successfully achieved by the best vocalists and writers.

“There is no love except in silence and silence doesn’t say a word.” (31)

Angels and shadows

“The Delmore Brothers – God, I really love them. I think they’ve influenced every harmony I’ve ever tried to sing. This Hank Williams thing with just him and his guitar – man, that’s something, isn’t it? I used to sing these songs way back, a long time ago, even before I played rock and roll as a teenager. Sinatra, Peggy Lee, yeah. I love all these people, but I tell you who I’ve really been listening to a lot lately – in fact, I’m thinking about recording one of his earlier songs – is Bing Crosby. I don’t think you can find better phrasing anywhere.”

Bob Dylan (32)

Anyone active on social media in 2016, and following Bob Dylan’s summer tour, will know that fans are very divided. Some like the fact that he has taken time out to cover a selection of Sinatra standards, and others are bemoaning the set lists. Dylan’s last two albums have been dedicated to cover versions of songs previously recorded by Frank Sinatra, and it seems certain that there were enough studio recordings to fill a third, fourth, and fifth album.

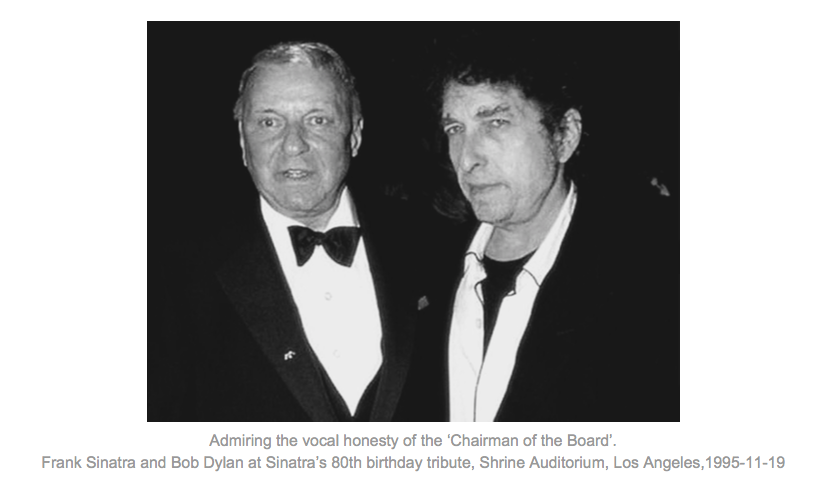

Shadows In The Night (2015), Fallen Angels (2016), and Triplicate (2017) may have perplexed and frustrated some fans, who have been waiting since Tempest in 2012 for a new album of self-penned Dylan songs. However, this departure will have come as no surprise for those who had followed interview comments that showed respect for the ‘crooners’ like Sinatra and Bing Crosby, the admiration and esteem showed by Bob Dylan during his performance of ‘ Restless Farewell ’ at Frank Sinatra’s 80th birthday tribute gala.

Born in 1941, young Robert Zimmerman was a child of the 1940s and 1950s. Rock and roll would have hit the teenage rebel with passion. However, the earliest musical influences he must have heard on the radio would have been the formative background soundtrack of his childhood – Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, Peggy Lee, Hank Williams. Composers such as Johnny Richards, Carolyn Leigh, Johnny Mercer, Hoagy Carmichael, Harry Ruby and Bert Kalmar, Rube Bloom and Sammy Gallop, Peter DeRose and Billy Hill. They wrote Bob Dylan’s earliest musical lexicon. Is it so surprising that he wants to record his tribute to their art?

Bob Dylan was listed as a mourner at Frank Sinatra’s funeral, and it was reported that he attended the vigil the night before the mass. (33) Dylan’s official statement was poignant and heartfelt.

“Right from the beginning he was there with the truth of things in his voice. His music had a profound influence on me, whether I knew it or not. He was one of the very few singers who sang without a mask. It’s a sad day.”

It is interesting that the most integral point for respect and admiration was Dylan’s approval of how Sinatra ‘sang without a mask’. This from a performer who has utilised masks and personae and obfuscating vagueness to the greatest effect throughout his whole career.

Perhaps what Dylan is striving for in these cover albums is to touch a piece of that openness and honesty – the almost childlike naivety of those songs. If these songs are important to Bob Dylan as influential childhood memories, it is a valuable decision to commit his interpretation of them.

Because they are not really ‘cover’ songs at all. They are ‘uncoverings’ as explained by Dylan himself when he said:

“I don’t see myself as covering these songs in any way. They’ve been covered enough. Buried, as a matter a fact. What me and my band are basically doing is uncovering them. Lifting them out of the grave and bringing them into the light of day.” (34)

If Dylan believes in the raw honesty and unmasked authenticity of Frank Sinatra’s singing, then surely each cover performed by others is a literal cover. It adds a blanket of detraction and muddiness to the songs. Just as in his MusiCares speech he railed against singers who sing “every note that exists, and some that don’t exist,” (35) it would not be a stretch of the imagination to consider that Bob Dylan had heard just so many karaoke versions of ‘My Way’ before deciding to rediscover these monumental iconic songs and bring them back to their simple roots of truth about the human condition – love, loss, struggle and joy.

And Bob Dylan’s voice and delivery is without doubt the high point of the current albums.

Melodiously sliding through the tunes with a smoothness that might not out-croon Sinatra, but that certainly surprises. His pared back arrangements are almost ‘cowboy’ in style, with Donnie Herron’s pedal steel guitar and viola replacing the orchestral and big band sweeps that backed Ol’ Blue Eyes. Dylan’s voice might strain for some of the higher notes, becoming a little hoarse on the longer held notes… but there is a clean and clear, enunciated and cared-for, respect for the lyrics and melodies.

On Shadows In The Night, Fallen Angels and Triplicate , Bob Dylan’s voice and phrasing captures the haunting melancholy, the sadness that never becomes bitter, the aching loneliness, the timelessness of unsentimental nostalgia. His voice is smoky and familiar, yet unique. He vocally inhabits and evokes this black and white world. It is as natural to him as breathing. His phrasing on All The Way for example. Listen to how he runs phrases together so smoothly, taking pauses to emphasise certain words, holding certain notes, allowing others to trail off into silence, and hitting the final high note with clarity and a touch of vulnerability. Consider the vocal dexterity (and the well-held alveolar hissing sibilant /s/ in ‘kiss’, sounding just like the cooling effect on the protagonist’s heated desire) of That Old Black Magic , and contrast it with the slow underplayed drama of Come Rain or Come Shine, or the well-placed and gentle tremolo effect used sparingly during It Had To Be You .

When talking about Frank Sinatra, Bob Dylan once said, “The tone of his voice, it’s like a cello.” (36) We can see in these three albums (Triplicate being Dylan’s first triple album of 30 songs) that Bob Dylan is also using his voice like another instrument. To list adjectives I thought of when listening to the albums, Dylan’s voice alternates between percussive, velvety smooth, teasing, witty, sustained and understated, undulating, and (of course) melancholy.

Dylan is totally correct that these are not ‘cover songs’. They are an exploration of the great American Songbook, a rediscovery of truthful and heartfelt music, nostalgia and memory without the dripping sentimentality.

And if the split reaction of fans to the recent albums is anything to go by, the reaction when he finally puts out the often hinted at traditional polka album, well, that will be even more remarkable!

Nobel Prize for Literature, 2016

“Yea, but you’re not talking about Nobel Peace Prizes, you know. Come on, let’s… you know really.”

Bob Dylan (37)

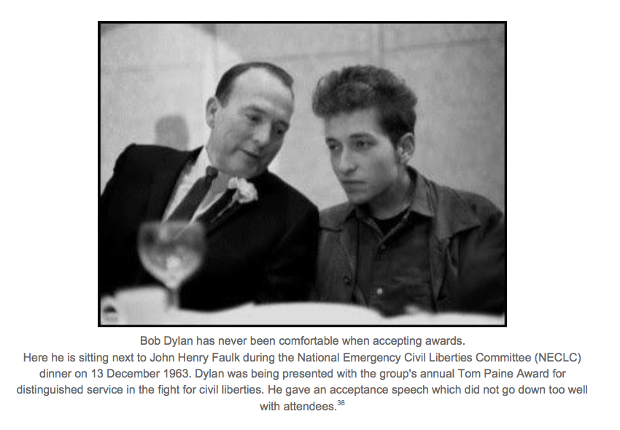

Gordon Ball, a teacher at the Virginia Military Institute (39), outlines in his essay Dylan and the Nobel (40), how in 1996 he endorsed an application to the Nobel Committee of the Swedish Academy nominating Bob Dylan for the Nobel Prize for Literature. He admits that he is not a Dylan fan and his area of related expertise is the study of Allen Ginsberg and Beat Generation literature.

Before briefly discussing the role of Dylan’s voice in the consideration for the Nobel, it is first worthwhile taking the time to understand the nomination process.

Each year the Swedish Academy sends out requests for nominations of candidates for the Nobel Prize in Literature to Members of the Academy, members of literature academies and societies, professors of literature and language, former Nobel literature laureates, and the presidents of writers’ organizations. By April, the Academy narrows the field to around twenty candidates.

By May, a shortlist of five names is approved by the Committee. The subsequent four months are then spent in reading and reviewing the works of the five candidates. In October members of the Academy vote, and the candidate who receives more than half of the votes is named the Nobel Laureate in Literature.

No one can get the prize without being on the list at least twice, thus many of the same authors reappear and are reviewed repeatedly over the years.

Thousands of people send in unsolicited suggestions for Nobel Prizes. Only the Swedish Academy sends out requests for nominations of candidates to be considered for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

However, it is interesting as an exercise to consider the questions – how did Bob Dylan make the running for, and in 2016 winning, a Nobel Prize, regardless of the logistics and reality of nominations? And to what extent is his vocal delivery, combined with the oral tradition of his music, a contributing factor?

It is clear that Bob Dylan satisfies the Nobel Prize criteria in that the nominees for the Literature award should be reflecting idealism and integrity in addressing the human condition. Most people would agree that in these fields alone, Bob Dylan’s music has excelled over several decades. It is the literary element which draws debate, and is doing so today in the light of Dylan’s victory. Dylan’s best lyrics certainly can be read as poetry, and are all the more powerful in performance. So why would people question whether Bob Dylan is a suitable Nobel winner?

It might be a consideration that the perception of the songwriting art has been denigrated during the rise of the more vacuous ‘pop song’. This might create a preconceived notion that rock music is created solely for marketing and saleability, is not a poetic art form, and is limited in scope and structure by the constriction of the musical boundaries. Whether this preconception can be overcome is an interesting question. However, if we look at the history of poetry and song, the oral tradition, we can see that there is solid reason to accept a singer songwriter, moving away from the western shift that elevated the written word above the spoken, chanted or sung forms.

The Nobel committee has given awards to dramatists, mixed-media artists and orators (such as Winston Churchill in 1953, who beyond his written work was praised for his speeches and the effects they had in defending human values). So why not a lyricist?

In Greek lyric poetry the word ‘lyric’ is used because the poems were from the tradition of poetry sung or chanted to the accompaniment of the lyre. It is also known as ‘melic’ poetry from the word ‘melos’ meaning “song”, from which we get the English word ‘melody’. In this sense, it is difficult to point to another iconic artist who has contributed more to re-establishing the high poetic form in modern culture. Bob Dylan embodies the oral traditions of balladeers and troubadours or Greek lyric poets, in combination with poetic and literary influences that permeate his work. (41)

And on a world stage Bob Dylan echoes the traditions of Nobel Prize winner Rabindranath Tagore or even the Bauls of Bengal who felt most at home visiting Bob Dylan in Woodstock. Wandering singers, learning from everyone and everything, sharing knowledge and insight and a love of wild living.

The last outback at the world’s end

I feel it is fitting to conclude with a quotation from Bob Dylan’s speech at the 2015 MusiCares Person of The Year ceremony, February 6th, 2015. Dylan said:

“Sam Cooke said this when told he had a beautiful voice: He said, “Well that’s very kind of you, but voices ought not to be measured by how pretty they are. Instead they matter only if they convince you that they are telling the truth.” Think about that the next time you are listening to a singer.” (42)

Think about that the next time you are listening to Bob Dylan.

More phases than the moon: an addendum

Only the mediocre are always at their best.”

Jean Giraudoux (43)

Readers who are familiar with Bob Dylan’s oeuvre can undoubtedly reel off an extensive list of songs where they have heard Bob Dylan’s voice do something different or extraordinary. However, for more casual listeners I am including here a playlist of a few songs, in addition to the songs already mentioned above, where to hear them, and their release information. These songs are just a small sample of Bob Dylan’s voice fulfilling some of the effects mentioned above – representing a different character, utilising silence and pauses, integrating phonological modifications, exemplifying ambiguity of meaning through vocalisation and related methods.

LAST THOUGHTS ON WOODY GUTHRIE

Recorded live at Town Hall, 12 April 1963

Released on The Bootleg Series, Volumes 1-3, 1991

This is a spoken poem, not a song. The words here tumble quickly and to the edge of breath in parts. Dylan’s accent, his use of contractions, his beautiful imagery, assimilation and elision, His youthful voice rolling from one phrase to another, sometimes running lines together without pause, taking breaths whenever possible, pausing in unusual places, vocally jumping from one idea to the other, the beat and rhythm pounding like the rattle of the ‘fast flyin’ train on a tornado track’, seeking the answers to the questions and despair talked about in the verse. The journey takes us from rural idylls to the slums and ‘trash can alleys’ of urban decay, and it is incredible to hear someone who was only 22 years old at the time so artfully dissect the materialist society and the way that we are duped into seeking for answers in all the wrong places. The voice appears to have lived longer than the body it inhabits.

HOUSE OF THE RISING SUN

First performed at The Purple Onion or Bastille, St. Paul, Minnesota, June 1960

Recorded at Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, New York City, New York, 20 & 22 November 1961

Released on Bob Dylan, 1962

A young Dylan tells the story of a woman from a troubled family who ends up in a women’s prison in New Orleans, with a voice of such authenticity that a listener would have trouble finding fault with his singing from a woman’s point of view.

See also, Dink’s Song , The Home Of Bonnie Beecher, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 22 December 1961. Released on The Bootleg Series (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991, Volume1 (1991) and also on The Bootleg Series, Vol 7: No Direction Home (2005).

BLACK CROSS

The Home Of Bonnie Beecher, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 22 December 1961.

Released on The Bootleg Series (Rare & Unreleased) 1961-1991, Volume1 (1991).

Black Cross (Hezekiah Jones) was written by Joseph Simon Newman who was the uncle of the actor Paul Newman. It was most famously performed by Lord Buckley (who had a substantial effect on Bob Dylan’s creative development). It is a harrowing moral tale of a southern lynching of a self-educated black man, and we can hear the spoken vocal effects of Bob Dylan as he tells the story. The rhythm and prosody, the drawled voices, the bellow of the preacher, the croak of sarcasm in the white lynch mob, the volume and tone and different accents catching the true nature of the characters in the tale.

SHE BELONGS TO ME

Recorded at Studio A, Columbia Recording Studios, New York City, New York, 14 January 1965.

Released on Bringing It All Back Home (1965)

Ambiguity. Who is ‘she’? What is the relationship between the singer and the female character? In the album version and subsequent live performances, vocal nuance and phrasing leads the listener down different paths.

ONE MORE CUP OF COFFEE (VALLEY BELOW)

Recorded at Studio E, Columbia Recording Studios, New York City, New York, 30 July 1975.

Released on Desire (1976).

A example of cross-cultural vocal assimilation and prosody, One More Cup of Coffee (Valley Below) is a part of an album that has the protagonists searching for pyramids embedded in ice, visiting the beaches of Mozambique, escaping bandits in Durango, exploring very real legal injustice, and facing the (natural and human) chaos in Black Diamond Bay. Bob Dylan’s powerful voice here captures it all, with the gypsy feel of those on the fringes of society, the outcasts and outlaws. Dylan’s voice in the song reflects a Jewish cantor, gypsy music, and Arabian influences.

PRETTY SARO

Recorded at Studio B, Columbia Recording Studios, New York City, New York, 3 March 1970.

Released on The Bootleg Series, Vol. 10: Another Self Portrait (2013).

Bob Dylan changes his voice and delivery style for these recording sessions. Here he takes the 18th century English ballad and sings it with a sweet and simple ‘crooning’ quality.

If anyone ever tells you that Bob Dylan can’t sing, play them this one song.

TELL ME MOMMA

Recorded at the Free Trade Hall, Manchester, England, 17 May 1966.

Released on The Bootleg Series, Vol 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966 (1998).

Full-fledged rock star mode. The glissando, the elongated vowels, the beautifully vocalised howl, the assimilation.

STUCK INSIDE OF MOBILE WITH THE MEMPHIS BLUES AGAIN

Recorded at Columbia Music Row Studios, Nashville, Tennessee, 17 February 1966.

Released on Blonde on Blonde (1966).

For listeners wishing to hear what Bob Dylan called ‘that thin, wild, mercury sound’, Tell Me Momma played live, and Stuck Inside of Mobile With The Memphis Blues Again , are classic examples.

“The closest I ever got to the sound I hear in my mind was on individual bands in the Blonde on Blonde album. It’s that thin, that wild mercury sound. It’s metallic and bright gold, with whatever that conjures up. That’s my particular sound. I haven’t been able to succeed in getting it all the time. Mostly, I’ve been driving at a combination of guitar, harmonica and organ, but now I find myself going into territory that has more percussion in it and [pause] rhythms of the soul.” (44)

I THREW IT ALL AWAY

Recorded at Columbia Studio A, Nashville, Tennessee, 13 February 1969.

Released on Nashville Skyline (1969).

This is pure Nashville. Bob Dylan family man; with a country style and a clean cut, down home feeling, but enough metaphorical lyrics to tip a sly wink and remind us that we are still firmly in Dylanesque territory. The deeper, more laid-back and softer vocal style is a nod to Hank Williams and the formative country singers of his youth, and Dylan chose to sing I Threw It All Away as the first of his three songs he performed on Johnny Cash’s inaugural television show. The show was filmed at the Ryman Auditorium, Nashville, Tennessee, 1 May 1969 and broadcast on 7 June that year. The video clips are usually available online in various places and are well worth watching to see how Bob Dylan combines a change of physical look, dress, vocal style and facial expression to project a very different persona to that of his tour in 1966, which many of the viewers might have been expecting. He looked right at home sitting next to Johnny Cash at the Ryman Auditorium in the heart of the Grand Ole Opry .

LO AND BEHOLD!

Recorded at Big Pink’s Basement, Stoll Road, West Saugerties, New York, May-October 1967.

Released on The Basement Tapes (1975).

This song is representative of the vocal style(s) being produced at Big Pink with The Band in 1967. Raw, rough and real. Mistakes left in. Chuckle and coughs as friends on the same creative pathway experiment with lyrics, melodies and sounds. The almost spoken and drawled verses are well timed with a mixture of well placed pauses, an expressive vocal effect with the change of syllable emphasis on ‘behold’ to place the stress on the first syllable, a beautifully rounded pronunciation of ‘mound’, elongated vowels, hurried words in parts, elision, assimilation and a general conversational prosody that counterbalances the almost howled but harmonised chorus.

AIN’T TALKIN’

Recorded at Sony Music Studios, New York City, New York, February-March 2006.

Released on Modern Times (2006).

An encapsulation of Bob Dylan’s voice as an elder statesman of the damned. Interestingly sung in the first person, we feel that the character here is still active in the fight, still making his way through the ‘cities of the plague’, His heart is still burning and yearning for change. This is not a game, it is very real, and he is considering who remains loyal in the battle. However, there is a weariness, a concern that he is losing his powers, and a decision that despite the seeming futility, action is still the best way forward.

Dylan’s voice here is clear in articulation, the slight understated growls, the clipped enunciation, the emotion of repressed frustration in the structure and formality that counterbalances the chaos and pain. There is a nice contrast between the elongated vowels and the punctuated rhythm of intricate lines such as ‘ I’m not nursing any superfluous fears .’ Like the protagonist, his voice falls and rises, growls, wanders, burns its bridges, and wearily warns his enemies not to mess with him before disappearing over the horizon.

ALL THE WAY

Recorded at Capitol Studio A Hollywood Los Angeles, February / March 2014.

Released on Fallen Angels (2016).

It is difficult to select a song to encapsulate for the listener the quality of Dylan’s voice on what have been dubbed the ‘Sinatra albums’ (45) as they are all fine examples of a versatile voice in full form. The album Shadows In The Night had a more melancholy atmosphere. Mellow and smooth, it still leaves the listener feeling somewhat lost and alone in this noirish and umbrageous world. Fallen Angels has a more upbeat feel, more of the big band atmosphere, and Dylan’s voice reacts to the change of tempo and attitude – or, more accurately, his voice sets the tone. Triplicate is a fine mixture of playful, upbeat and heartbroken melancholy.

All The Way is a slower song, a timelessly simplistic and lyrical pledge of eternal loyalty that doesn’t need any bells and whistles or vocal tricks. This is a song that shows how Bob Dylan can still vocally express a melody with tuneful clarity, honesty and authenticity. Clear, strong, an edge of vulnerability, and the essence of the human need for commitment and trust.

Footnotes:

1 Thorn, Max. “What Does Dylan’s Voice Sound Like? Let the Critics Tell You”. Vulture 13 September 2012 http://www.vulture.com/2012/09/what-does-bob-dylans-voice-sound-like.html Accessed on 2016-07-19

2 Pareles, Jon. “From Romance to Carnage: Review: ‘Tempest’ by Bob Dylan” New York Times 10 September 2012 http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/11/arts/music/bob-dylan.html?_r=2&adxnnl=1&adxnnlx=13 47479494-gOM1BXqIGXc3FvYgz1QzzA Accessed on 2016-07-19

3 Daly, Sean. “Review: Bob Dylan’s new album ‘Tempest’ is breathtaking but bleak.” Tampa Bay Times 10 September 2012 http://www.tampabay.com/features/music/article1250790.ece Accessed on 2016-07-19

4 Petridis, Alexis. “Bob Dylan: Tempest – review: Dylan’s latest is angry, growling and mostly great fun. But comparing it to his best work is way over the top”. The Guardian 6 September 2012 http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2012/sep/06/bob-dylan-tempest-review Accessed on 2016-07-19

5 Bowie, David, “Song For Bob Dylan” Hunky Dory . RCA, 1971. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Song_for_Bob_Dylan

6 Billany, Fred. “A Wandering Troubadour With No Message For Anyone” Newcastle Evening Chronicle 4 May 1965 www.edlis.org/word p120-121

7 “Let Us Now Praise Little Men.” Time Magazine 31 May 1963, www.edlis.org/word p62

8 Horace Judson interview, Savoy Hotel, London, England 9 May 1965. Pennebaker, D A. Bob Dylan: Dont Look Back. New York: Ballantine Books, 1968. www.edlis.org/word p151

9 Lebold, Christopher. “A Face like a Mask and a Voice that Croaks: An Integrated Poetics of Bob Dylan’s Voice, Personae, and Lyrics.” Oral Tradition Volume 22, Number 1. March 2007 http://journal.oraltradition.org/files/articles/22i/Lebold.pdf Accessed on 2016-07-19

10 Lynch, Declan. “Bob Dylan: 75 years of total misunderstandings.” Irish Independent . 29 May 2016 http://www.independent.ie/opinion/columnists/declan-lynch/bob-dylan-75-years-of-total-misunderstandings-34754849.html Accessed on 2016-07-19

11 Rimbaud, Arthur. Letter to Georges Izambard; Charleville, 13 May 1871, https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Lettre_de_Rimbaud_%C3%A0_Georges_Izambard_-_13_mai_1871 Accessed on 2016-07-19

12 The quote has been attributed to many people. Actor George Burns also put it in his own 1980 memoir. The joke has been traced to a 1962 newspaper column by Leonard Lyons, in which actress Celeste Holm quotes an unnamed actor saying, “Honesty. That’s the thing in the theater today. Honesty… and just as soon as I can learn to fake that, I’ll have it made.” Burns, George. The Third Time Around. New York: Putnam, 1980.

22 Buck, Gary. Assessing Listening. [Online]. “What is unique to listening” Cambridge Language Assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2001 http://www.cambridge.org/download_file/591332/0/ http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9780511732959 Accessed on 2016-07-19

13 Gross, Jason. “Simon Frith Interview by Jason Gross” Perfect Sound Forever. May 2002 http://www.furious.com/perfect/simonfrith.html Accessed on 2016-07-19

14 Echard, William. Neil Young and the Poetics of Energy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005. Pages 194 – 197

15 “Paul Simon Gets Personal in New Rolling Stone Feature” Rolling Stone 28 April 2011 http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/paul-simon-gets-personal-in-new-rolling-stone-feature-20110 428 Accessed on 2016-07-19

16 Dylan, Bob “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.” The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. Columbia 1963 http://bobdylan.com/songs/dont-think-twice-its-all-right/ Accessed on 2016-07-19

17 Smith, Joe, and Mitchell Fink. Off the Record: An Oral History of Popular Music. New York: Warner Books, 1988.

18 ‘Human brain becomes tuned to voices and emotional tone of voice during infancy.’ Eureka Alert 24 March 2010 http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2010-03/cp-hbb031910.php Accessed on 2016-07-19

19 Prosody (linguistics) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prosody_(linguistics) Accessed on 2016-07-19

20 Rings, Steven. “A Foreign Sound to Your Ear: Bob Dylan Performs “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009” Music Theory Online Volume 19, Number 4, December 2013 http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.4/mto.13.19.4.rings.php Accessed on 2016-07-19

21 Bays, Jeffrey Michael. “Sound: Hitchcock’s Third Dimension” Borgus June 2011 http://borgus.com/hitch/sound.htm Accessed on 2016-07-19

Definitions:

Assimilation in phonological modification, is when sounds influence the pronunciation of adjacent words in a way they wouldn’t be pronounced separately. So ‘won’t you’ often is spoken as ‘wonchoo’ or ‘didn’t you’ becomes ‘dinchoo’.

Elision is when a sound at the end of a word is dropped in everyday speech. Dropping the /g/ from the end of ‘blowin’’, or running two words together such as ‘nexday’ instead of ‘next day’, and ‘kind of’ becomes ‘kinda’.

Intrusion is introducing a new sound between words to ease the flow of speech. So, for example, an /r/ between the word ‘far’ and a vowel at the beginning of the next word. In English the final /r/ is usually silent in the word ‘far’, yet we clearly sound out the /r/ when saying ‘far away’.

Sandhi is the process whereby the form of a word changes as a result of its position in an utterance (for example, the change from a to an before a vowel).

23 Snedekera, Jesse and Trueswellb, John. “Using prosody to avoid ambiguity: Effects of speaker awareness and referential context” Journal of Memory and Language 48. 2003. http://www.ircs.upenn.edu/~truesweb/trueswell_pdfs/2003_JML48_103-130.pdf Accessed on 2016-07-19

24 Dylan, Bob ‘I Shall Be Free No. 10.’ Another Side Of Bob Dylan . Columbia,1964. http://bobdylan.com/songs/i-shall-be-free-no-10/ Accessed on 2016-07-19

25 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomorrow_and_tomorrow_and_tomorrow

26 Bob Dylan, at the San Francisco press conference, 3 December 1965. www.edlis.org/word p243

27 Dylan, Bob ‘Highlands.’ Time Out Of Mind. Columbia,1997. http://bobdylan.com/songs/highlands/ Accessed 2016-07-19

28 Dylan, Bob. ‘The Groom’s Still Waiting At The Altar.’ Shot of Love . Columbia, 1981 http://bobdylan.com/songs/grooms-still-waiting-altar/ Accessed on 2016-07-19

29 Dylan, Bob, Christopher Ricks, Lisa Nemrow, and Julie Nemrow. The Lyrics: Since 1962 , 2014. Page 628

30 Anderson, Randy. An interview with DYLAN. The Minnesota Daily , 17 February 1978. www.edlis.org/word p594

31 Gleason, Ralph J. “The Children’s Crusade.” Ramparts March 1966. www.edlis.org/word p304

32 Gilmore, Mikal. “Bob Dylan – After All These Years In The Spotlight The Elusive Star Is At The Crossroads Again.” Los Angeles Herald Examiner 13 October 1985. www.edlis.org/word p885

33 A note from Bob Dylan, Frank Sinatra’s funeral service, Good Shepherd Catholic Church, Beverly Hills, California, 20 May 1998. See www.edlis.org/word p1230

34 Greene, Andy. “Bob Dylan Releases Frank Sinatra Cover, Plans New Album.” Rolling Stone Magazine 13 May 2014 http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/bob-dylan-releases-frank-sinatra-cover-plans-new-album-201 40513 Accessed on 2016-07-19

35 “Read Bob Dylan’s Complete, Riveting MusiCares Speech: Dylan thanks his supporters, denounces his detractors in epic acceptance speech” Rolling Stone 6 February 2015 http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/read-bob-dylans-complete-riveting-musicares-speech-20150 209 Accessed on 2016-07-19

36 Gates, David. “Dylan Revisited.” Newsweek 6 October 1997. www.edlis.org/word p1192

37 Elliot Mintz interview for the Westwood One Radio Station three hour broadcast, Los Angeles, March 1991. Transcript can be read at www.edlis.org/word pages 1090-1100.

38 Bob Dylan Revisited. “Bob Dylan and John Henry Faulk.” 26 April 2012 https://plus.google.com/114972365014876681245/posts/D3yfaiSfXp9 Accessed on 2016-07-19

39 Gordon Ball biography http://www.gordonballgallery.com/gordon_ball_bio.htm Accessed on 2016-07-19

40 Ball, Gordon. “Dylan and the Nobel.” Oral Tradition Volume 22, Number 1. March 2007 http://journal.oraltradition.org/issues/22i/ball Accessed on 2016-07-19

41 Greek lyric poetry https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_lyric Accessed on 2016-07-19

42 “Read Bob Dylan’s Complete, Riveting MusiCares Speech: Dylan thanks his supporters, denounces his detractors in epic acceptance speech” Rolling Stone 6 February 2015 http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/read-bob-dylans-complete-riveting-musicares-speech-20150 209 Accessed on 2016-07-19

43 This quotation has been attributed to many writers. Giraudoux quoted in: Principal, Victoria. The Beauty Principal. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984. Page 117

44 Rosenbaum, Ron. “Playboy Interview, Bob Dylan: a candid conversation with the visionary whose songs changed the times.” Playboy- Entertainment for Men March 1978. See www.edlis.org/word p534 – 555

45 Here I would note that a Frank Sinatra song is rarely one with lyrics or music written by Frank Sinatra. A Frank Sinatra song usually refers to a song performed by Frank Sinatra.

(c) Tara Zuk, 2017

All Rights Reserved