Bluegrass Goes Electric: Country and Rock & Roll Influence the Genre

Bill Monroe once said in an interview with George Gruhn: “Bluegrass is a pure music. You follow the melody right, and you don’t put in no hot, know-it-all fiddle that don’t belong in there” (Ewing 2006, p. 195). Bluegrass music as we know it today was created by Monroe and the particularly cultivated sound of his band, the Blue Grass Boys, in the 1940s; although the naming of ‘bluegrass’ as a widely- accepted genre did not occur until a decade or so later (Rosenberg 2005, pp. 95-9). Building off influences from earlier string bands and genres such as old-time, hillbilly, and gospel, Monroe experimented with several musicians, styles and sounds until he settled up on those that are now seen as the benchmark criteria for bluegrass bands worldwide.

Bill Monroe

In L. Mayne Smith’s article, “An Introduction to Bluegrass,” he describes this sound as a “…style of concert hillbilly music performed by a highly integrated ensemble of voices and non-electrified stringed instruments, including a banjo played Scruggs style” (Goldsmith 2004, pp. 79). The non- electrified stringed instruments in particular most commonly consist of an acoustic guitar, 5-string banjo, mandolin, fiddle, and an upright bass. These instruments, with their lead and rhythmic roles, respectively combined, produced the high-lonesome sound that made Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys a commercial success in the mid-1940s to the present day. Despite this, early configurations of Monroe’s band included an accordion, played by “Sally Ann” Wilene Forrester, a pianist, and a harmonica player (Rosenberg 2005, pp. 62-65). Furthermore, as bluegrass began to progress through the years, more and more bands began to experiment with variations in instrumentation as a way to appeal to wider audiences and set themselves apart stylistically from the other bands on the touring circuit.

Following the vast successes of rock n’ roll and the British invasion in the early 1960s, many music genres were struggling to stay prominent on the charts and with the fan bases of younger generations. Bluegrass was no exception. Additionally, the peak of the folk revival in the mid-1960s brought with it drastic effects to the genre. A massive, electric revolution would soon supervene upon tradition, changing bluegrass for the next several decades to come.

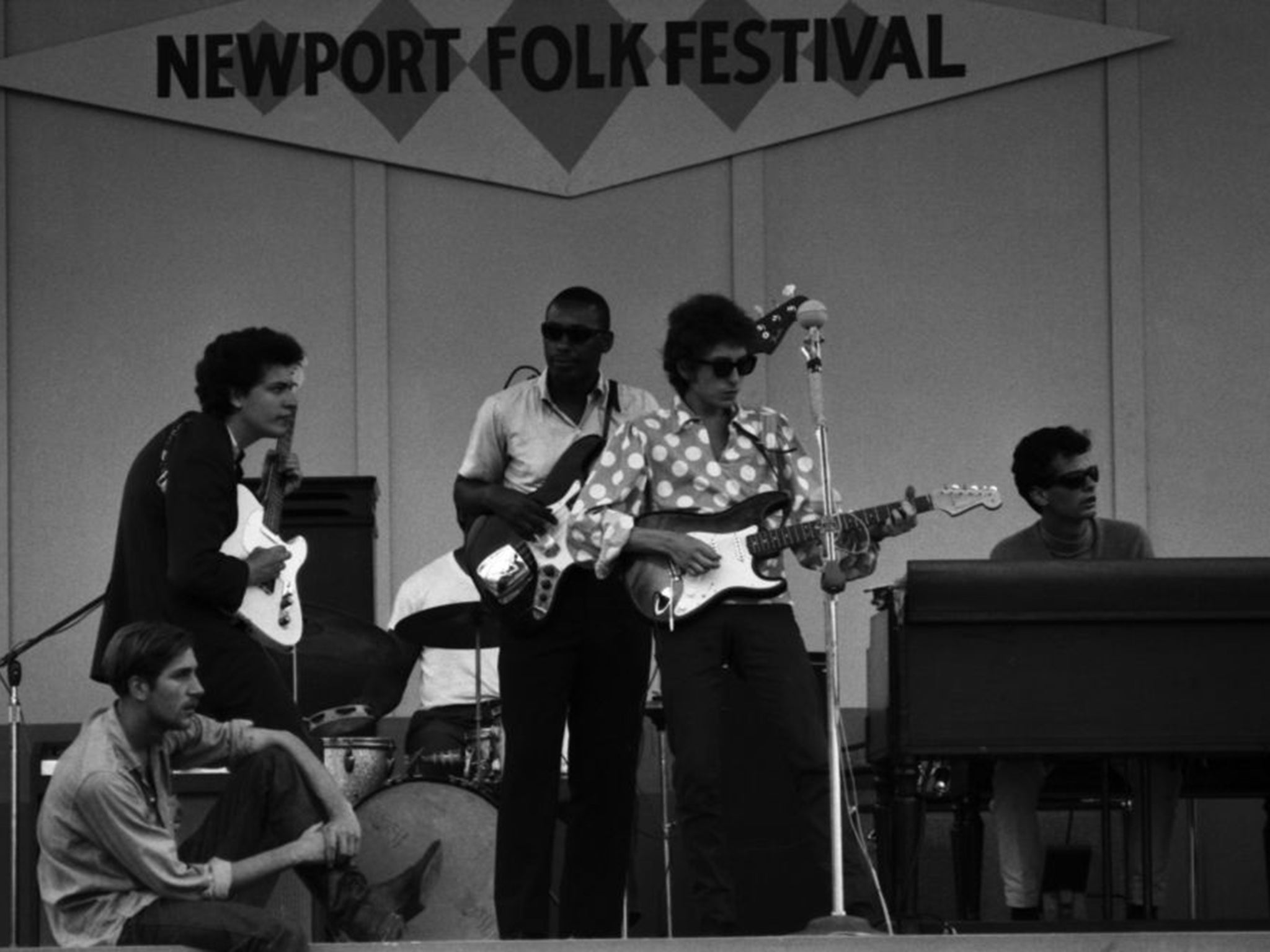

As rock n’ roll continued to gain national success, electric instruments, including guitar, bass and pedal steel guitar, as well as percussion became the industry standard. So much so that typically folk acoustic artists started varying their sound. Bob Dylan went electric, much to the dismay of many fellow artists and fans, for the first time live at the Newport Folk Festival on July 25, 1965 (Wald 2015). Thus began a moving trend towards amplification in music which bluegrass must rival.

Dylan Goes Electric at the Newport Folk Festival, 1965

The Sixties was a defining decade of sorts for bluegrass music. Television shows such as The Andy Griffith Show (1960) and The Beverly Hillbillies (1962) regularly featured bluegrass performances and songs, resulting in a population surge for the genre. Additionally, Hollywood films such as Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and later, Deliverance (1972), utilized bluegrass music in efforts to portray hillbilly lifestyles and cultures, both positively and negatively. All the while, bluegrass and folk music festivals began to grow in both size and frequency of occurrence. Perhaps most noticeably, the diversification of audiences at these festivals became more and more prevalent.

In Chapter 11 of Neil Rosenberg’s book Bluegrass: A History, he explains: “While festivals began to catch on in the late sixties, the phenomenon was not large enough to support very many bands on a full-time basis…and major record companies and radio stations…did not see much value in bluegrass as a commercial music” (Rosenberg 2005, pp. 305).

In reaction to this dying commercial market of bluegrass, several bands during this time either separated or shifted towards more lucrative styles of music, including Nashville-sound country, country-rock and folk-rock (Rosenberg 2005, pp. 305). The effects these changes had on bluegrass were essentially due to the younger musicians’ desires to innovate artistically. Rosenberg explained that they had always faced pressures to play more commercialized music, which was different from the goals of their elder colleagues who wanted to preserve the pure, traditional bluegrass sound. Few bands did attempt to assimilate however, by way of adjusting their marketing strategies, concert repertoires and overall stylistic approach. For some, this assimilation into new, hyphenated music genres proved overall to be successful, but reception from diehard fans of the genre was mostly negative.

The Osborne Brothers were one of the earliest pioneers of integrating bluegrass music with the new country sounds of Nashville. All the while, they were able to maintain a consistent, strong following in the bluegrass community, gaining newer fans along the way with their fusion with country music. According to Rosenberg, “they had been using drums on their records since 1957 and had acquired a reputation for experimenting in the studio” (Rosenberg 2005, pp. 311). Three years later, they became one of the first bluegrass bands to include electric instruments in the recording studio in 1960. They recorded 4 songs with MGM on November 15, 1960: “Fair and Tender Ladies,” “Each Season Changes You,” “Black Sheep Returned to the Fold,” and “At the First Fall of Snow.” These songs were the first of the band’s career recorded with a pedal steel guitar and an electric guitar in the mix (Goldsmith 2004, pp. 71). According to Sonny Osborne, the band chose to do so because they needed something to fill in the spaces of the songs. Despite being one of the leading bands to take such a daring leap in the recording studio, the songs were well received by bluegrass audiences.

The Osborne Brothers – Camp Springs Bluegrass Festival, 1971

Next, in 1966, the band enlisted blind piano extraordinaire Hargus “Pig Robbins” to play on “their biggest hit to date, ‘Up This Hill and Down’” (Rosenberg 2005, pp. 311). By 1966, Robbins had already established himself as a well-known session player in Nashville, playing on George Jones’ 1959 number one single “White Lightning,” as well as albums by Patsy Cline, Ray Price, Ernest Tubb and Bobby Bare. Over the next few years, the Osborne Brothers would continue to experiment, adding an electric bass player to their touring band, and calling upon the pedal steel talents of Hal Rugg to record “Rocky Top” on December 25, 1967 (Thompson 2011). Shortly after the release of “Rocky Top,” bluegrass fans that were once supportive of the group’s musical output began to disapprove of the new direction.

In 1969, The Osborne Brothers committed their biggest act of bluegrass betrayal to date, or so thought traditional bluegrass fans: they went electric. “’It’s the same damn thing as a good PA system’,” Sonny Osborne told interviewers from Bluegrass Unlimited (Rosenberg 2005, pp. 312). By adding pickups to their instruments, the band’s sole intention was to raise their overall volume level, not change their sound by any means. Referring back to the definition of bluegrass in L. Mayne Smith’s article, “An Introduction to Bluegrass,” bluegrass is traditionally played with non-electrified stringed instruments. To hardcore bluegrass traditionalists, the Osborne Brothers had broken a Cardinal rule of the genre and festival promoters refused to book groups that toured with electric instruments.

Despite much criticism towards their creative approach throughout the mid- to-late 1960s, the Osborne Brothers still remained successful in the bluegrass circuit. “They released their 1970 studio album Ru-bee-eee with Pig Robbins and Hal Rug returning to attribute piano and pedal steel to the album, respectively. Also, in 1971, the group appeared at the Camp Springs bluegrass festival near Reidsville, North Carolina. At Camp Springs, the band’s instrumentation included Ray Kirkland on electric bass, Robbie Osborne on the drum kit, and Ronnie Reno playing an acoustic guitar with a pickup (Frobbi 1). Bobby’s mandolin and Sonny’s banjo were also played with electronic pickups. A DVD entitled Bluegrass Country Soul that was released in 2006 showcases the many acts that performed at the 1971 festival. Of the performances on video is the Osborne Brothers singing “Ruby,” where the drum kit and what look to be Fender amplifiers for each instrument are clearly seen. A few years later in 1974, the group decided to stop using the electric instruments that had been at the heart of so much debate and denigration for the past decade. Nevertheless, their musical marriage of genres proved to be effective because “their own vocal and instrumental work retained its appeal and because they had an attractive repertoire of…Nashville tunes…with older songs of [Bill] Monroe]” (Rosenberg 2005, pp. 314).

Jim and Jesse, another popular Grand Ole Opry act, were enjoying some successes amongst a mix of folk, bluegrass and country audiences in the mid-1960s, releasing six albums on the Epic record label. The duo was touted as one of the premier bluegrass acts in the country and was invited to officially join the Opry in 1964. Like other bluegrass groups of the decade, however, they too began to feel the pressures forcing them towards more commercialized genres (Rosenberg 2005, pp. 315). In 1965, the McReynolds brothers, Jim and Jesse, released a rock n’ roll- inspired bluegrass album of Chuck Berry tunes. A mild sales success, Berry Pickin’ in the Country featured all the traditional, acoustic instruments typical of true bluegrass, but failed to place the brothers on the Billboard charts.

Jim and Jesse

The next year, Jim and Jesse released the most country album of their career to date, Diesel on My Tail. The brothers “were ready to, as Jim says, ‘take a stab at country music’,” and their stab proved effective (Goldsmith 2004, pp. 76). Featuring hefty country doses of Lloyd Green’s pedal steel guitar, Diesel on My Tail peaked at #18 on the Billboard charts on June 17, 1967 (Billboard 1967). The album, produced by renowned Nashville producer Billy Sherrill included hit country songs such as Del Reeves’ “Girl on the Billboard,” Buck Owens’ “Sam’s Place,” and Dave Dudley’s “Six Days on the Road.” Following the newly found success of their first country album, Jim and Jesse decided to stab a little deeper for a few more years to come. The brothers released several country albums with bluegrass flare into the early 1970s, including some instrumental albums. In 1970, Jim and Jesse released the album We Like Trains, with Lloyd Green returning to provide steel.

Diesel on My Tail (1967)

Though Jim and Jesse McReynolds had seemingly been primarily focused on country music for the better half of the late 1960s, they never fully abandoned their roots: pure bluegrass music per the Monroe standard. Jim and Jesse, though frequently denied electric instruments at festivals, were always prepared with a repertoire and instrumentation most comforting to the bluegrass traditionalists. At Monroe’s Bean Blossom Festival on June 17, 1972 for instance, Jim and Jesse performed a set that included a bluegrass version of “Diesel on my Tail.” The song was well received by the crowd (Frobbi 2). Additionally, further into the 1970s, acoustic music started to recapture its ground in commercial music mediums and festivals soon became more occurring. “…With bluegrass festivals comprising 90 percent of their work, the group phased out the electrified country sound completely” but not before leaving their mark on both bluegrass and country music for years to follow (Goldsmith 2004, pp. 77).

While it may seem like all genres of music, including bluegrass during this period wanted the commercial success that country music in Nashville was enjoying, bluegrass was creating its own profound affect. During the 1960s folk revival, bands such as The Byrds and The Flying Burrito Brothers from the west coast began forming a blend of psychedelic folk-rock music, largely influenced by the impact of bluegrass at the time. The Byrds initially consisted of three folk revivalist performers: Roger McGuinn, Gene Clark and David Crosby (later of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young fame), before filling the electric bass spot with Chris Hillman and drums with Michael Clark. The group released their first Columbia album, Mr. Tambourine Man, a defining folk-rock debut, featuring three Bob Dylan-penned songs on June 21, 1965. It is interesting to note that Dylan went electric at the Newport Folk Festival almost exactly a month later.

Mr. Tambourine Man (1965)

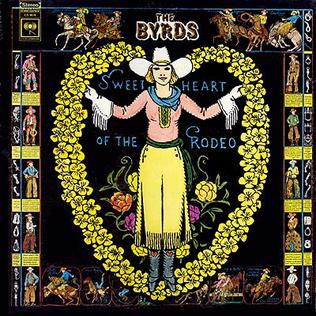

In 1968, The Byrds, now without Clark and Crosby, gained a new member in vocalist and rhythm guitarist Gram Parsons. Parsons quickly asserted his own musical agenda on the band: one that was heavy in both country style and repertoire. A few months after Parsons’ arrival, the Byrds traveled from Los Angeles to Nashville to begin recording their upcoming album Sweetheart of the Rodeo, set for release in August. The session boasted veteran pedal steel players JayDee Maness and Lloyd Green, pianist Earl Poole Ball, John Hartford on banjo, and 24- year old guitarist Clarence White, who would later become a full-time member of the band (Rosenberg 2005, pp. 316). The names Hartford and White should sound familiar to bluegrass fans, the latter a past member of the Kentucky Colonels along with his brother Roland.

On March 15, 1968, while in Nashville recording Sweetheart of the Rodeo, the Byrds landed a spot on the Grand Ole Opry (Betts, 2016). The now country-rock band was not extremely well received by audiences, yet this did not discourage Roger McGuinn and the Byrds. He recalled in a 2010 interview with Nashville Scene: “There were indeed some folks attending…who didn’t seem to appreciate how sincere we were in doing country music…” (Betts, 2016). Overall, both chart performance and reception of the Byrds’ Nashville project was mediocre and the eventual departure of Parsons before the album’s release dissolved the current band lineup.

Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968)

This musical impact of the Byrds would quickly find its way to another California-based band. Back in Los Angeles, “The Dillards returned to the studio…to make their first album since 1965. For the first time, they included a pedal steel [Buddy Emmons], electric bass, and drums. And banjoist Doug Dillard had been replaced by Herb Pedersen…” (Rosenberg 2005, pp. 331). Pedersen, a California native, had a strong influence on the Dillards’ new sound, which was strikingly similar to that of the Byrds. The Dillards’ 1968 release of Wheatstraw Suite was sonically the polar opposite of their previous traditional bluegrass albums such as Back Porch Bluegrass (1963) and Pickin’ and Fiddlin’ (1965), and certainly not in line with their Hollywood portrayal of the bluegrass-picking Darling family on The Andy Griffith Show. This new “west coast sound,” as it came to be known, included a doubling of vocal harmony parts and orchestral strings which many bluegrass fans found to be too much of a poppy, mainstream Nashville sound (Rosenberg 2005, pp. 332). While The Dillards were experimenting in the studio with Wheatstraw Suite, former member Doug Dillard was doing some experimenting of his own, developing a new group. Bernie Leadon, who would later achieve fame as the last founding member of the Eagles, former Byrd drummer Gene Clark, and Dillard would come together to form and release two albums as the Dillard and Clark Experience. After Leadon and Clark’s departures, Dillard’s newest lineup “…Played much more bluegrass than the earlier version of the Expedition but, like the other L.A. groups mentioned, melded rock, country, folk, and bluegrass elements in various ways…” (Rosenberg 2005, pp. 332).

The Dillards

An audio recording on Fred Robbins’ website from 1970 at a venue called House of the Rising Sun demonstrates the bluegrass proficiency of the groups newest lineup, which featured Byron Berline, and Roger Bush and Billy Ray Latham from the Kentucky Colonels (Frobbi 3). The group performed a largely bluegrass repertoire, with the fiddle and banjo performing most of the breaks and lots of vocal harmony.

As the 1960s came to an end and country music had cemented its place in bluegrass music, more and more bands began to follow the previously set trend by the likes of The Osborne Brothers, Jim and Jesse and The Dillards. In 1973, J.D. Crowe & the New South released the Bluegrass Evolution album, featuring Tony Rice on vocals. This project, filled with country pedal steel and drums, was Crowe’s first attempt at fusing traditional country and bluegrass sounds. He followed up this release with the 1978 and 1979 releases You Can Share My Blanket and My Home Ain’t in the Hall of Fame, respectively.

“We were straddling the fence,” says Crowe in the liner notes of the 1979 album, which included 25-year old Keith Whitley on lead vocals and Nashville’s Doug Jernigan on pedal steel (See Attached Analysis). Whitley of course would go on to have his own successful career in country music in the mid-to-late 1980s (Mitchell, n.d.). Rick Anderson wrote in an AllMusic review: “to call this album ‘progressive bluegrass’ would be rather misleading. Basically, this is a honky-tonk album with a banjo and a few bluegrass numbers thrown in…but bluegrass purists should consider themselves duly warned” (Anderson, n.d.). Crowe and company played a show at Kosei Nenkin Sho Hall in Japan on April 18, 1979, with a set comprising of mainly bluegrass songs including “Foggy Mountain Breakdown,” “Footprints in the Snow,” and “Blue Moon of Kentucky.” Despite not having drums or pedal steel however, the group still chose to include several country tunes in their repertoire. The set included songs from the 1979 album, as well as classics like John Conlee’s “Rose Colored Glasses” and Willie Nelson’s “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” (Frobbi 4).

Keith Whitley with J.D. Crowe

J.D. Crowe & the New South continued to revive the genre of bluegrass even after Whitley left for Nashville. With their fresh, progressive approach to the music, they, along with other forward-thinking bands such as New Grass Revival and Breakfast Special opened the doors for future groups to do the same through the 1980s. John Cowan spoke of his time as bassist with New Grass Revival in Smoky Mountain News:

“It was ‘us versus them,’ ‘them’ being our parents’ generation. It was so broad, culturally speaking, that it worked its way down into the bluegrass world we lived in. There was this whole thing about, ‘those kids are on drugs, they’re ruining our music, they’re plugging their instruments in.’ We were kind of offended because we loved Flatt & Scruggs and Bill Monroe…” (Woodward 2017).

New Grass Revival

Bluegrass fans were not the only ones taking notice of the new, electric changes in the style of these bluegrass bands. Other bands on the festival and recording circuit were noticing as well. Some noticed their successes and followed suit as aforementioned, and others just did not understand the hype. In a 1974 interview in Pickin’ magazine with Charlie Waller of the Country Gentlemen, he was asked what he thought of the attraction of some groups toward amplification and drums. Waller responded:

“Well…if that’s what they want. I think if a lot of work and effort has been put into making a good guitar then it should be heard as an acoustical instrument. I think an electric bass is acceptable. However, it doesn’t have stage appeal. I’ve always been able to go along with the sound of an electric bass, but I don’t see having drums or at least carrying drums. I have nothing against the slight help with drums on the rhythm side if you’re making a record” (Goldsmith 2004, pp. 172).

Pedal steel guitarist JayDee Maness had an interesting perspective on his role in bluegrass going electric as well: “As a country musician, I learned something very important…that steel guitar can fit into any kind of music, if it’s allowed.” To conclude, the significance of the country-folk music of The Byrds and the underlying bluegrass influences of The Dillards, The Osbornes, Jim and Jesse and Crowe during this time may have ruffled the feathers of traditional bluegrass fans and performers such as Bill Monroe, but it helped provide the framework for future evolutionary bluegrass bands to shape the genre, thus allowing it to grow and flourish. While Mr. Monroe may have thought “no hot, know-it-all fiddle” had a place in his bluegrass world, it is likely he never anticipated the day electric guitars, electric basses, pedal steels and drum kits would take the stage and change “the story of bluegrass” forever.

Works Cited

Anderson, Rick. “My Home Ain’t in the Hall of Fame – J.D. Crowe & the New South.” AllMusic. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

Betts, Stephen L. “Flashback: The Byrds Flip the Opry Script.” Rolling Stone. Rolling Stone, 15 Mar. 2016. Web. 27 Apr. 2017.

Bluegrass Country Soul. Dir. Albert Ihde. Time Life Records, 2006. DVD.

Ewing, Tom. The Bill Monroe Reader. Urbana: U of Illinois, 2006. 195. Print.

Goldsmith, Thomas. The Bluegrass Reader. Urbana: U of Illinois, 2004. Print.

Frobbi 1

http://frobbi.org/audio/ivor/Camp_Springs_71/osbornes/index.html

Frobbi 2

http://frobbi.org/audio/ivor/3DVDs_2/CD%2009%20(1972-06- 17)%20Beanblossom%20Vol%204%20D2/index.html

Frobbi 3

Frobbi 4

http://frobbi.org/audio/ivor/3DVDs_3/JDCrowe-(1979-04-18)-Tokyo/index.html J.D. Crowe and the New South. Tennessee Blues. James Dee Crowe, 1979. MP3.

Mitchell, Bob. “J. D. Crowe – My Home Ain’t In the Hall of Fame.” Louisville Music News. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 Apr. 2017.

Rosenberg, Neil V. Bluegrass: A History. Urbana: U of Illinois Pr., 2005. Print.

Thompson, Richard. “On This Day #5.” Bluegrass Today. N.p., 25 Dec. 2011. Web. 23 Apr. 2017.

Wald, Elijah. Introduction. Dylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties. NY, NY: Dey St., 2015. N. pag. Print.

Woodward, Garret K. “Smoky Mountain News.” Lonesome and a Long Way from Home: John Cowan on Bluegrass, Life. N.p., 8 Feb. 2017. Web. 29 Apr. 2017.

Wynn, Ron. “How Miles Davis Helped The Byrds, and Why Guitarist Roger McGuinn Likes the Internet.” Nashville Scene. N.p., 27 May 2010. Web. 26 Apr. 2017.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1456636-1221103689.jpeg.jpg)