Blues and Black folk music shine on the American Titanic

Acknowledgments:

I thank Robert Sacré and Alan Balfour for putting at my disposal earlier publications. Ray Templeton, Paul Petraitis and John Clarke kindly pointed me to interesting song recordings.

—————————————————————-

When I told my 12 year young daughter, Blijke, after having watched the Cameron block buster on the Titanic, that I intended to write an essay on the depiction of this disaster in the African-American folk and blues, she answered with a smile that I could only read as: “Dad, you are making fun of me”. As some of you will confirm, a teenage daughter is not to be fooled. During an earlier perusal of disaster topics in black folk and blues, I had stumbled across some songs on the sinking of the Titanic. Quickly after confirming the idea of my new subject, I found some of the old Titanic songs collected on a 3 CD-box, named “People Take Warning” (Tompkins Square, 2007), which contains a larger anthology of natural and accidental songs from the white and black American folk repertory. It opens with a song, waxed in 1932, on the 1912 shipwreck. A friend pointed me, furthermore, to a 1998 CD, issued by the Teagarden label, assembling a selection of eighteen songs, mastered from the original 78-records, exclusively on the Titanic drama. In vain, I tried to get a hold of it, despite my intense search driven too by the accompanying superb booklet.

Back to literature, and to ITunes, it did not take much effort to catalog a slew of other, more recent, blues songs that have been issued. Just a random grab out of them: Bessie Jones, a gospel singer who learned her songs from her grandfather, a slave in Africa, immortalized the tragic event twice, once in 1961 and again in 1973. In 1980, Flora Molton, often presented as an unsophisticated version of Sister Rosetta Tharpe, brought her version of ‘‘The Titanic’’. John Koerner, who in 1965 debuted with “Spider Blues” and appeared at the Newport Folk Festival, issued his ‘‘Titanic’’ in 1992, followed six years later by Rory Block. In 2003 Abi Wallenstein, a German blues performer, recorded his ‘‘Titanic’’ (Monge, 2006). There was thus, contrary to my daughter’s skepticism implicit in the smile she gave me that day, definitely a subject to write about. After all, why should the blues repertory have been immune for the Titanic-mania? There is hardly a medium (cartoons, poems, films, songs, advertisements …) which does not have it on its program in whatever form or style. The 1912 disaster has entered the collective memory in the Western world, and became part of our vocabulary. Captain Edward Smith’s order: “Women and children first” is now a popular phrase. The commemoration events organized this year, a century after the shocking event, contribute even more to anchor it as a part of our culture, reminding us, amongst other things, that we should not boast on the human and technological invincibility in the face of nature’s force. So, why should the blues have remained deaf for it? It did not, as a quick glance on the blues discography had learned me.

Yet, at the same time, I realized that there exist equally valid arguments which would have made it comprehensible why the Titanic event could have been absent from the blues’ performers playlists. How can we explain that folk music focuses on an event that transcends the local or regional, and even national interest, and entered the lore only through newspapers? Obviously, printed culture influenced black, oral culture. Is this not contradicting our concept of folk music origins? An even more solid argument for a possible exclusion of the Titanic topic by blues and black folk interest would have been the distinct fact that the African-American populace was in no way involved in the disaster. It is only much later that records revealed the presence of one black passenger, a Haitian with French nationality, married to a white woman. Why have the blues and black folk lore turned to an event that in no way touched the African-American populace? It is evident that the 1927 Mississippi flood, or the Natchez dance hall fire in 1940 (I will come back on those) entered the blues song lists; however, why has the Titanic sinking also been promoted to a topic in black vernacular song whilst there was no immediate, direct relation to the black population?

Furthermore, bearing in mind that the black folk and blues are an expression of the personal and communal experience of the performer who, through his song, voices his emotions and comment on the white oppressive system, it became for me even less obvious why blues and black artists have paid any attention at all to an event from which only white citizens suffered. The blues are a translation of the way African-Americans handle the hardships of the daily life; the sinking of the Titanic did not in any way enter the circle of the personal or group experience of the bluesman.

Finally, considering the social and economic position of the black populace in America at the time of the disaster, and during its following decades, there is enough reason to explain why the sea disaster would not have aroused any, or very little attention within this group. The African-Americans suffered under the consequences of the “Separate but equal”- doctrine denying them equal political, social, educational, and economic opportunity. Racial oppression was in place throughout the nation, and the “Jim Crow” laws were in their heydays. Contrary to their white fellow Americans who enjoyed the fruits of the nation’s wealth, freedom, and opportunity, African-Americans were systematically ripped of their civil and political rights and their labor was exploited. Why then should a ship that hit an iceberg with aboard an exclusive white passenger group have bothered them? Plenty of natural or accidental disasters in America have added further misery to the black populace already victim of social oppression. The sinking of a “white-lily” vessel did in no way add to it. The observation that most of the black press hardly considered the sea disaster as news (Biel, 1996) is indeed more in line with expectations, that the struggle for black civil rights and the fight against the widespread lynching was a bigger concern for the African-Americans than the telegraphs reporting a Liverpool registered vessel having struck an iceberg. From the perspective of the black populace, it was hard to see any real meaning in the accident to justify its promotion to a news item in the press.

Nevertheless, it did not last long before black folk song and culture integrated the topic in its repertory. Huddie Leadbetter remembered to have worked together with Blind Lemon Jefferson around 1912, recalling precisely the period because one of the songs they did together was a ballad about the Titanic (“Fare Thee Well, Titanic”) (Wolfe, Lornell, 1999). Later, in the 1940′s, Leadbelly stated that “The Titanic” was the first song he ever learned to play on a 12-string guitar.

In 1913 Butler “String Beans” May bragged that he himself was aboard the ship, and survived due to his great athleticism (Rice, 2003). Called the “young lion” of the African American vaudeville, String Beans was probably the first black star whose professional success did not depend upon the mainstream approval. It is said that he has originated the blues metaphor of “Elgin movements” (1), which he combined with the theme of the sinking Titanic in a piano play called “Titanic Blues”. As an eyewitness, teacher and folklorist W.L. James has described String Beans’ performance vividly as follows: “As he attacks the piano, Stringbean’s head starts to nod, his shoulders shake, and his body begins to quiver. Slowly, he sinks to the floor of the stage. Before he submerges, he is executing the Snake Hips…, shouting the blues and, as he hits the deck still playing the piano, performing a horizontal grind which would make today’s rock and roll dancers seem like staid citizens.”

Later in the 1910′s, before commercial blues recording kicked off, black folk songs about the sea catastrophe are reported to have been collected, as early as 1915, in a wide geographic area of Alabama, the Carolinas, Georgia, and Mississippi. A Titanic-related song, ‘‘When That Great Ship Went Down’’, is documented to have been sung in 1920 by a black musician in North Carolina. The folk collector Newman Ivey White noted in 1928, by the way, that these early songs are marvelous examples of how, by improvisation and combining of verses from different, older songs, new songs were composed fitting contemporary subjects, such as the Titanic sinking (White,1928: 346).

The black interest in the Titanic remained much alive after the spectacular entry of the blues on the record market, though it will always be impossible to discern to which degree the initiative for selecting the topic came from the performer him/herself, the record company, or the folk collector. Because I don’t aim completeness, it suffices here to cite just a few examples. In December 1925, Ma Rainey recorded the ‘‘Titanic Man Blues’’, followed a few months later by the “Titanic Blues” staged by the blues and jazz singer Virginia Liston, who seemed to have been inspired by Rainey’s version (Mike Ballantyne). Two years later, Richard ‘‘Rabbit’’ Brown, one of a group of important artists preceding the development of 1920’s acoustic blues, waxed ‘‘Sinking of the Titanic’’. Making his living as a ferryman, rowing locals and visitors on Lake Pontchartrain (South-eastern Louisiana), Richard Brown apparently understood what he was singing about, bringing a rather detailed picture of the shipwreck. The song, recorded by a field unit of the Victor Company in New Orleans, brought him by the way recognition seldom given to a songster in his time (Bluesnexus). It was on the 10th of April on a sunny afternoon

The Titanic left Southampton, each one as happy as a bride and groom

No one thought of danger or what their fate may be

Until a gruesome iceberg caused 1500 to perish in the sea

It was early Monday morning, just about the break of day

Captain said call for help from the Carpathia and it was many miles away

Everyone was calm and silent, asked each other what the trouble may be

Not thinking that death was lurking there upon that northern sea

The Carpathia received the wireless SOS re distress

Come at once, we are sinking, make no delay and do your best

Get the lifeboats all in readiness ‘cos we’re going down very fast

We have saved the women and the children and tried to hold out to the last

(…)

Blind Willie Johnson’s ‘‘God Moves on the Water’’ (1929), one of the seminal blues songs, presents us another version of “the Great Titanic [that] struck an iceberg”. Mance Lipscomb states that he learned the song from Willie Johnson.

A few prewar noncommercial topical songs on the subject are known to have been recorded for the Library of Congress. Huddie Ledbetter’s noncommercial recording titled ‘‘The Titanic’’ (1935), was already part of his repertoire, as noted above, under the title ‘‘Fare Thee Well, Titanic’’ when he played with Blind Lemon Jefferson the same year the ship went down (Wolfe and Lornell, 1994: 44). Leadbelly seemed to have had a good feeling to attract attention by customizing his songs to recite news headlines. In his song “Hindenburg disaster” for instance, he describes the spectacular 1937 fire of the German passenger ship.

Guitarist Hi’’ Henry Brown (not to be confused with the pianist Henry Brown) waxed his version of ‘‘Titanic Blues’’ in 1932 in a pure twelve-bar AAB form.

The Second World War did not taper the popularity of the Titanic theme. Leadbelly’s “Last Sessions” from 1948 included again his rendering of the Titanic. When in the early 1950’s the Piedmont style guitarist Pink Anderson – who had learned his finger picking on the road in the 1910′s when he travelled with a medicine show – went back in the studio, he sang his interpretation of the 1912 disaster. Mance Lipscomb, who had never recorded until he was discovered in the 1960’s blues revival, deposited too his Titanic song at the vinyl, a version which he, as I already mentioned, reputedly learned from Willie Johnson.

Leadbelly’s rendering of the Hindenburg disaster shows that blues and black folk sometimes looked beyond the black community impact of a tragedy. Much the same can be concluded from Sam Hopkin’s pronounced attention for hurricanes and storms in songs such as “That Mean Old Twister”, “Hurricanes Carla and Esther”, and “Hurricane Betsy”, to quote only a few. His disproportional concern with this natural phenomenon was related, probably, to his strong fear of flying (a fear to which I subscribe, by the way).

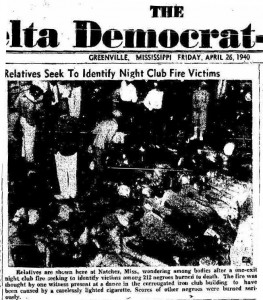

Generally, however, the disaster songs by African-Americans concentrated on catastrophes that hit them and their communities in a direct or indirect way. One of the greatest river floods of the United States, The Mississippi River Flood in 1927, for instance, has resulted in a large number of calamity songs. To cite only one: “High Water Everywhere”, which is regarded to be among the finest recordings made by Charley Patton The great drought that affected almost two-thirds of the country in the 1930′s, just at the moment when there was some hope to recover from the Great Depression, was depicted in a.o. Son House’s “Dry Spell Blues”. The “Dust Bowl “was the worst and most prolonged environmental disaster in American history, and dramatically impacted the African-Americans living from agriculture. Noteworthy is also the fire in the night of April 23, 1940 in The Natchez Dance Hall, Mississippi, burning more than 200 black victims, and leaving only 17 survivors. Young black clarinetist Walter Barnes, playing that night with his sixteen-piece Chicago orchestra, one of the nation’s best swing bands, was one of the casualties. Despite its mostly regional resonance, the dance hall holocaust reverberated in a relatively important number of songs, of which Howlin’ Wolf’s 1956 “The Natchez Burnin’” is but one example. All in all, the sinking of the Titanic in the night of April 14th 1912 has thus resulted in a high number of black songs, despite the absence of a direct or indirect effect on the black community. Why?

Of course, we cannot make abstraction from the substantial scale of the disaster, which remains one of the most deadly transport disasters in history. The human loss was severe. If we want to understand, however, its relative significance as a topic of black folk music and blues, we need in the first place to look at the way the calamity has been presented by the mainstream Anglo-Saxon culture. More than a reaction to the factual sinking of the vessel, the black vernacular response was a reaction to the way the Anglo-Saxon media and popular culture interpreted and framed the accident. As Steven Biel (1996) has convincingly highlighted, the ship disaster gained a particular cultural significance as an event “of deep and wide resonance in Progressive era America. Besides shock and grief, the disaster produced a contest of meaning that connected the sinking of an ocean liner on calm seas in April 1912 with some of the most important and troubling problems, tensions and conflicts of the day. () It was a () highly dramatic moment, a kind of “social drama” in which conflicts were played out and American culture, in effect, thought out loud about itself” (203).

Therefore, it is justified to elaborate somewhat on the main elements of the Anglo-Saxon response.

THE PASSENGER LIST OF THE TITANIC: WOMEN, CHILDREN, HEROES AND COWARDS

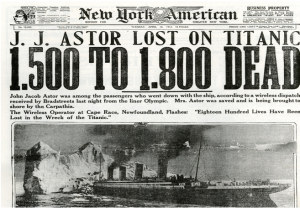

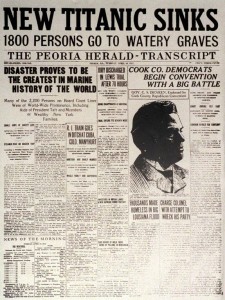

Browsing through the newspaper editions that appeared on Monday 15th and Tuesday 16th 1912, we notice there is at first large uncertainty about what actually happened. There is unbelief also as to the possibility even of any casualty. The wireless telegraph was not that efficient yet as to allow for a spread of news at the rate to which we are accustomed today. In any case, it feels strange, reading the articles, how in the first editions, confirmation was still given by the White Star Line office in Britain that everything was under control, and that the vessel was heading, using its own power, towards New York.

Already then, however, there was also pure cold and material speculation whether the ship and the passenger’s property were appropriately insured. The “New York Tribune” of April 16th reports on its front page that the owners were unable to insure the Titanic to the full amount “because the British and European markets were not big enough to absorb the sum”. The newspaper further contends that, “in addition to a valuable shipment of diamonds aboard the Titanic, it is said that among almost priceless jewels carried by the passengers, are pearls, belonging to an American woman, valued at $ 600.000“. It finally adds that the steamer “also carried a large amount in bonds and a very valuable registered mail.” This very article appeared at the bottom of the very same front page that heads: “1.340 perish as Titanic Sinks; only 886, mostly women and children, rescued“…

In the following weeks and months, when most of the relevant details were available, the mainstream feeling about the disaster took shape in official declarations, commercial press, magazines, sermons, eulogies and popular songs. It is instructional to posit the white comments against the backdrop of the initial presentation of the Titanic. Before all, the ship was seen as British, and was hence almost as decorated with patriotic and imperial signifiers as any British Royal naval ship. When the ship left the docks, British imperial power was at its zenith. The steamer was to meant be a record breaking engine, a proof of the power and global reach of the British Empire: the naming itself “TITANIC” highlighted its imperial might. It was presented as a symbol of modernity and industrial and technological strength.

More as a hidden agenda, it stood too for the growing influence of American capital. In fact, in 1902 the financial ownership of the White Star Line had passed from British into the American hands of financier J.P. Morgan. Even the seagoing rules under which it operated were not British, but American. Only the appearance of control had stayed in Britain. As such, the Titanic was a symbol for the establishment of a white hegemony on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. The whole idea of the ship testified to a racialist-white and imperialistic ideology; it was in no way a sign of a universal humanism. In the first place, the ship was heralded as a superb expression of white, Anglo-Saxon heroism (Campbell et al., 2004).

A good deal of the white public debate about the Titanic debate was centered on the concepts of guilt and heroism. Of course, there was an official investigation which materialized in the Titanic hearings conducted by a special subcommittee of the Senate Commerce Committee. In addition to making recommendations for legislation, the committee examined the role of the different actors. Though no particular persons were named as being responsible, the final report nevertheless points to questionable behavior by some, and guilt by others “of the most reprehensible conduct.”

The cross-Atlantic, joint American-British solidarity that underpinned the enterprise did not stand the test when it came to discussing the responsibilities. Chauvinism popped up when it came to the point where fingers were pointed. Americans blamed J. Bruce Ismay, the British chairman of the White Star Line, who survived the disaster. He was highly ridiculed for his survival by both the press and the public. It was felt that Ismay, being president of the White Star Line, and thus also accountable for cutting on safety and giving priority to luxury, should have gone down too with the ship as the Captain did. One newspaper even dubbed him “J. (Brute) Ismay.” As a survivor, he was considered a villain, a coward, compared to for instance the American millionaire J.J. Astor, who died a hero. Heroes and cowards were the main actors in the mythsthat developed in the aftermath of the ship wreck. The former, in the Christian tradition, had sacrificed their life to enable the weaker women and children to reach the shore alive. Wealthy and successful men from first class had unselfishly died as heroes to save the lives of the weaker.

White, mainstream response made thus abstraction of gender, class and race relations and focused on the supposedly general human values of heroism and sacrifice to give meaning to the catastrophe. Typical for this paternalistic approach was the high value put on the chivalry deployed by those who had ceded their places on the life boats to children and women.

It is worth noting that the popular “women and children first” is neither a general human rule of conduct, valued at all places or at all times, nor a general maritime law. Whilst there was an earlier reference to the principle of ‘women and children first’ in the 1852 ship wreck of the Birkenhead, a troop ship, carrying 631 crew, soldiers and their families, and which foundered off the coast of South Africa, there are plenty of contemporaneous examples where there is no mention at all of invoking this principle. Quite on the contrary. The Amazon, a vessel that sunk in the same year as the Birkenhead, is a showcase of complete unconcern for the fate of women and children on the part of the crew.

The “women and children first” doctrine invoked in the Titanic debate was an exponent of the contemporary Victorian and Edwardian ideology promoting the idea of chivalry (Lucy Delap, 2006). The idea of protecting the weak women and children, and highlighting the bravery of men was foremost a celebration of the existing hierarchy between the genders. It deviated too the attention from the class (and race) relations concentrating on gender and age relations, irrespective of the social and economic context. The “Women and children” doctrine was supposed to bridge the divisions between the different classes and races, and formulate the relation between men and women solely in terms of human weakness and strength. The dominant white response to the sinking of the Titanic was, as a consequence formulated along concepts which were conservative, meaning that they corroborated the existing relations of power between men and women, and between the so-called higher and lower classes. The race aspect staid too out of scope.

MEN ARE NOT UNSINKABLE

The Titanic story, narrated in terms mainly of heroism and sacrifice, became an integral part of the popular white culture, implicitly reinforcing existing social relations, and thus inequalities. As such, it became part of the cultural layer of an American society that denied the equal access of black and white to social, political and economic rights. The black folk interest in the Titanic can best be understood as a response to this white story, more than as a reaction to the factual disaster itself. At the end of the day, the Titanic event was one more aspect, next to many others, that was a reason for a further comment by the African-Americans on the system that utterly oppressed them. In other words, the black vernacular Titanic story can be read as any other response to the many different ways the white society excluded blacks from equal sharing in the fruits of freedom and economic progress. The characteristics of this response were fully in accordance with those structuring black culture in general, and blues and folk music in particular. Essential is the act of “signifying” in this process by which the black community gave a meaning to the disaster.

The African-Americans re-interpreted the white story in their own terminology, reshaped and revised the script and even its actors to give expression to the same concerns which underpinned the total black folk and blues repertory. Biel (1996: 213) notes that not only the content of the story was revised, but that also the tone changed, and that the disaster was in some expressions even made into a joke. Humor and irony, as prominent features of black consciousness echo also in the black Titanic narration. In short, I would like to present the black folk disaster songs about the Titanic as an illustration of the basic set of style and creative elements that has shaped black folk song, and for that matter, black consciousness in general. The rewriting by black folk music and blues of the plot pertained to some of the essential lines and images of the white story: gender, spiritual meaning, class and especially race.

As for gender, “Titanic Man Blues” by Ma Rainey and J. Mayo Williams, recorded in New York in 1928, springs to mind. In this song, no explicit reference is made, however, to the disaster itself. When Ma Rainey sings “It’s your last time, Titanic, fare thee well”, she insults, in a disdainfully, haughty way her unfaithful man who wrongfully considered himself as “unsinkable” (S.R. Lieb, 1983). Her lover’s fortune has literally sunk, as did the steamer which name is used in the song as a metaphor. The lover’s overconfidence, which manifested itself in his having “a good time, drinking [his] high-priced wine” has eventually lead to the end of his love relation.

Opposed to the chivalry of the men on the Titanic, giving up their own life to save the life of women, Ma Rainey, brings to the stage a self-conscious, emancipated woman, who without mercy dumps her man. The acceptance of the existing gender relations, implicit in the conventional narrative, is unambiguously questioned in this song.

GOD WITH POWER IN HIS HAND SHOWED THE WORLD IT COULD NOT STAND

The spiritual meaningimparted to the event by the conventional, mainstream story was a showcase of the Christian value of sacrifice, articulating what Jesus meant when he declared that “The Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Mk 10:45). The male passengers of the Titanic, regardless of wealth and social standing, had put aside any concern about their own fate to save the lives of the weaker women and children. This heroic, Christian act of self-sacrifice was a central theme in the dominant interpretation of those terrifying midnight hours after the ship bell had alarmed the crew of the imminent danger. As Richard Howells (1999) writes: “The story of the Titanic was a story, for most, of men ‘going to their God’ with a hymn of faith”. The God whom this interpretation referred to was the gentle and redemptive God of the New Testament.

The black narrative did not focus on the individual acts of heroism and offering, but rather on the higher morality of the story embedded in the collapse of a human enterprise considered as a challenge to the rules of nature as laid down by God. The theological conclusion that African-Americans drew was one of “divine punishment for the supposed boast of the ship’s builders that God could not sink it” (Chris Smith, 1996). The featuring deity was the God of the Old Testament, the God who judges. Human power, in no form, can withstand the ultimate goal God has in mind with history and mankind. Thus, unlike the emphasis in the conventional narrative on the God of the New Testament, the God depicted by the African-American was the vengeful God of the Old Testament. It is the angry and wrathful, omnipotent God, without fear who is “king over all the children of pride” (Richard Howels, 1999), and who has sunk the Titanic. The ship is equated with an unnatural monster, a blasphemy because it was presented as unsinkable, while only God can decide on the fate of “things”. The sinking indicated the inevitability of God’s judgment “on the arrogance of those who believed themselves invincible” (Paul Oliver, 1984). As we know, the focus on the Old Testament is a leading guide to the way African-Americans have historically reshaped the conversion process into a value system that was congruent with their African beliefs and spiritual values. As J.W. Roberts (1989) has argued, the prominent role played by the actors of the Old Testament, and especially by Moses, who saved ‘his people’ from oppression in the land of Egypt, has been able to successfully enter the spirituals, because the Old Testament was reminiscent of the epic heroes present in African tales and praise poems. Consequently, it is no surprise that the black populace rather invoked the familiar God of the Old Testament instead of the New Testament God of mercy, sacrifice and redemption.

SO THEY PUT THE POOR BELOW

The moral and theological allusions did not question the existing social hierarchy, and certainly did not call to resistance or to oppression of injustices. In fact, the class dimension was to a (far) lesser degree than the other story lines of the white narrative the subject of the black vernacular reinterpretation. The version of “God moves on the water” recorded by Mance Lipscomb in 1964 includes a verse that reflects on the inability of the rich people to buy their safety (in: Chris Smith, 1996): “Jacob Astor was a millionaire,

Had plenty money to spare;

But when the Titanic was sinking,

Lord, he could not pay his fare.”

Pink Anderson’s version of the “The Ship Titanic” (1950) ironically observes that the “rich had declared they wouldn’t ride with the poor. So they put the poor below.” (Idem, 1996). The same comment on social hierarchy was present in the 1927 recording by William and Versey Smith.

More than any other, however, it was the race aspect, or rather the absence of any reference to race in the white interpretation, that gave rise to a fascinating revision of the Titanic story in the black popular culture. The act of “signifyin(g)” upon existing stories has shown itself here in its purest form, rewriting completely the tone of the plot, and bringing on stage new actors who gave a new turn to the events, and thus also to the social and moral conclusions drawn from them. The creativeness that flourished through this textual refashioning of the conventional Titanic narrative is, in other words, a speaking illustration of how black consciousness as a whole has taken shape in response to European values, with the main objective of offering the African-Americans the tools to maintain their identity and self-respect in the face of a dehumanizing system. Let us have a look at this new story and its main actors.

BLACK MAN OUTHTA SHOUT FOR JOY

Having the French nationality, the presence on the Titanic of the black Joseph Laroche, a Haitian-born, French-educated engineer, traveling with his (white) pregnant wife, Juliette, 22, and their two daughters, has been historically overlooked. It was only when James Cameron prepared the 3D version of his movie that a distant relative of Laroche fixed the attention to this historical inaccuracy. All conventional narratives on the Titanic have been based on the conviction that no blacks were aboard, neither as passenger, nor as member of the crew.

The black interpretation too was based on the absence of blacks on the vessel. There has been, in the early days, some wild speculation about the possible presence of a black stoker, but the trend of this rumor was clearly a mere confirmation of the ruling racist views. The story was that the black stoker had to be shot because he was about to stab the wireless operator Jack Phillip when he tried to grab the latter’s lifejacket (Philadelphia Tribune). This apocryphal black man was thus not presented as a hero, but as a villain, a coward (James Philip Danky,Wayne A. Wiegand, 1998). Anyhow, it was not more than speculation: both black and white narration started from the idea of the factual absence of black people on board.

Though the white exclusivity of the victims did not imply a total absence of mourning in the black community over the huge death toll, it was at the same time presented as an occasion for African-American celebration of survival (Alan J. Rice, 2003) (2).

Leadbelly leaves no doubt about this sentiment when he sings: “Black man oughta shout for joy,

Never lost a girl or either a boy.

Cryin’, “Fare thee Titanic, fare thee well!”

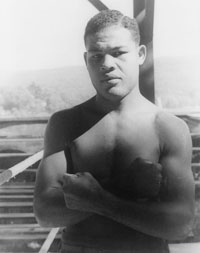

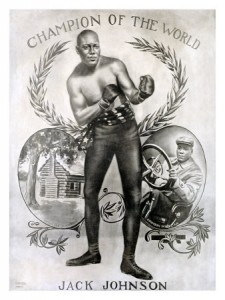

The celebrative sentiment is even reinforced and fused with irony by the rumor, elaborated in other black Titanic versions, that the only black passenger who wanted to buy a ticket was refused passage by the captain. Jack Johnson, nicknamed the “Galveston Giant”, the first African-American world heavyweight boxing champion, was said to have been turned down as a passenger even if he was at that moment one of the most famous and notorious African-Americans worldwide. The hypothetical refusal was not all that improbable, given that two years earlier Johnson had defeated, in what was then called “The Fight of the Century”, the white champion, Jeffries, thus knocking down, at the height of the Jim Crow segregation doctrine, dreams of undefeated white supremacy. Heavy race riots following the Johnson-Jeffries match illustrated the humiliation felt by the white community which had to endure the blacks’ celebrations of what they defined as a victory for racial advancement.

Jack Johnson’s supposedly exclusion as a passenger on a vessel that eventually went down in the ocean only articulated, and repeated the existing feeling of victory and celebration present already since this white boxer Jeffries had, in 1910, to throw in the towel, unable to challenge the superiority of the black boxer. When Jack Johnson heard the “mighty shock” of the sinking of the Titanic, Leadbelly had him, in another verse of the song, “doin’ th’ eagle rock”, dancing for pure joy, far away from the place of the catastrophe, safe on land. Note that the “Eagle Rock” was a popular black dance, performed with the arms outstretched and the body rocking from side to side. The image evoked by the song did thus not leave the slightest doubt on the sentiment of the singer and of his public.

JOE LOUIS KNOCKS DOWN THE GERMAN TITANIC

Already during slavery, some African-Americans had literally won their freedom in boxing games betted upon by plantation owners. It is thus not accidental, given the prominent place of boxing in the African-American (sports) culture, that in 1938 the persona of another boxer pops up when Bill Gaither records his “Champ Joe Louis”, just one day after Joe Louis won his rematch against the German Max Schmeling. Though Gaither has recorded hundreds of songs, partnered sometimes by Leroy Carr and Scrapper Blackwell, his most famous one was this particular song in which he linked the sinking of the Titanic to the 1938 triumph of Joe Louis over Schmeling in a world title fight over the heavyweight boxing crown. “I came all the way from Chicago to see Joe Louis and Max Schmeling fight.

Schmeling went down like the Titanic when Joe gave him just one hard right”

Joseph Louis Barrow, aka “The Brown Bomber”, born in Alabama 1914, and still considered by some as the best heavyweight boxers of all time, knocked down in a memorable fight the German champion Max Schmeling. The fight had a tremendous emotional and symbolic value, to such an extent that the match is still a seminal moment in African-American history. The German press had presented Schmeling’s earlier victory in 1936 over Louis as a proof of the superiority of the white race, and of the importance of keeping the “negro” in his place (Rice, 2003). The rematch was laden with meanings of white superiority versus black inferiority. Schmeling was on his trip in June 1938 to New York, where the fight took place, even accompanied by a Nazi party publicist. It is said that the prize money of Schmeling would be used to build tanks in Germany. Millions of radio listeners throughout the world however witnessed how Louis only needed two minutes and four seconds to bring Schmeling down. Bill Gaither cheerfully, in the wake of the match, compared the mythical unsinkable Titanic, also depicted 16 years earlier as a symbol of white superiority, to Schmeling’s supposedly invincibility. The sinking of the Titanic was again associated with moments of victory and joy for the African-Americans.

THE ONE TIME WHITE FOLKS AIN’T GONNA SHIT ON SHINE

Whilst Leadbelly and others dramatically changed the tone of the Titanic story, transforming the mourning in the white narrative to joy and cheerful dancing by the black community for the very absence of black passengers, other songs, curiously, added black personas on board of the ship. The cast of the narrativewas thus changed. Contrary to the story suggested in some white newspapers, the black passenger in this rewritten cast was however not a villain, but a hero, physically strong and clever enough to “save his ass.”

When in 1913 String Beans, a full blown star who had learned the job in Africa-American vaudeville, combined his quivering dancing in the “Elgin movements” with the theme of the sinking Titanic, he presented himself aboard the ship. Full of humor, he boasted how he could survive the wreck thanks to his superhuman prowess and athleticism (Niles, 1928). “I was on dat great Titanic

De night dat she went down

Ev’ybody wondered

Why I didn’t drown –

I had dem Elgin movements in my hips,

Twenty years’ guarantee”

There is an undeniable connection between String Beans’ presentation in 1913 and the highly popular toasts which appeared afterwards in a variety of versions (C.T. McCormick, 2011). Let us recall that toasts are long narratives, often in rhymed couplets, that mostly use “signifying” as a major feature. Next to the “Signifying Monkey”, the Titanic toasts featuring the Shine character were one of the most popular expressions of this black, rhetoric art form, having a very high appeal to the black community (3).

Shine is commonly staged as a lowly boiler room worker who rebelled against the ship’s captain, who stands for the ultimate white authority. He has many of the characteristics of the trickster figure, prominently present in African and African-American lore, who defies the power relations between black and white, and who uses his extra-ordinary capacities to acquire desirable goods. The trickster figure reverses the authority relation between the white and the black, between the socially strong and weak. The toast tells us how Shine warns the captain that the ship is about to sink, and how the captain ignores this warning and sends Shine back to the bottom of the ship to continue shoveling coal. Shine, however, refuses the order, jumps overboard and swims to safety. On his way, he meets sharks which he strongly outswims. In one of the versions, one of the sharks even stands by his side when it shouts: “Swim, black motherfucker, ‘cause I don’t like black meat” (Paul Heyer, 2012: 181). When the Titanic goes down, Shine is already safely back ashore.

Strikingly, Shine is offered money, sex and marriage in return for his help to escape other passengers, especially women. But, he rejects all.

Bruce Jackson has collected the following speaking version from a black convict at a Southeast Texan prison farm: “(..) I’m gonna try to save this black ass of mine.

So Shine jumped overboard and begin to swim,

And all the people were standin’ on deck watchin’ him.

Captain’s daughter jumped on the deck with her dress above her head

and her teddies below her knees.

and said, “Shine, Shine”, say, “won’t you save poor me?”

Say, “I’ll make you rich as any Shine can be.”

Shine said, “Miss, I know you is pretty and that is true,

but there’s women on the shore can make a ass out a you.”

Captain said, “Shine, Shine, you save poor me,

I make you as rich as any Shine can be.”

Shine say, “There’s fish in the ocean, whales in the sea,

captain, get your ass in the water and swim like me.”

In another toast version, one more black is staged next to Shine: Jim, who leaves the ship, as does Shine, but accepts the offer of the women. His fate is however sealed: “Jim climbed his black ass up on that ship, and we hear no more of him” (Heyer, 2012: 181). He dies with the white. The signifying in the Shine toasts is obvious. The white domination over the black is not universal, and once it comes to surviving, race, money and capital don’t matter. The toast challenges racism, white capital and inequality stemming from race and money. The traitor who succumbs to the white enchantments is doomed.

Beneath this obvious allusion to contemporaneous power relations, the Shine toast can even be given a deeper historical significance when its ingredients are linked to the transatlantic passage that brought the slaves from Africa to America. Shine manages to reverse completely the outcome of the Middle Passage: he becomes the winning economic trader who dominates the economic bargain over lives. Contrary to the slave merchant centuries before him, he is now able to negotiate with the white captain how to save his body. The white captain drowns and fails to make it to the other side of the Atlantic. Shine rejects monetary and other proposals, and it is this sensible decision which allows him to reach land, where he can fully enjoy the pleasures of life.

The symbolism of the highly popular Shine toasts can finally be stretched to the very concept of mobility itself. The white had purchased their mobility that eventually was paid too with their lives; the black, on the contrary, could choose their own mobility, out of their own free decision. The white mobility was an illusion; the black mobility to travel around freely was real. In this interpretation, the Shine toast is intertwined with the popularity of the travel metaphor in blues and black folk song (Chris Smith, 1996).

Obviously, not only the black populace has formulated its own Titanic “myth” as an alternative to the mainstream translation of the events. Political, left wing groups defined the Titanic as a symbol of the failure of capitalism, demonstrating the ultimate weakness of monetary power. The sinking of the steamer was also a beacon of hope that one day capitalism was to collapse. Feminists too challenged the ruling interpretation. For them, the advancement of the “women and children first”-principle was a mere translation of the questionable dogma that women were by definition the weaker, who, just as children needed protection. They even doubted whether it was really chivalry that admirably inspired men to offer their places on the life boats, or that it was not in the first place an unsinkable belief by men in the superiority of technology (4). Ann Larabee states for instance: “Although many men seemed to have behaved admirably…They may simply have had a cavalier trust in technology. Some did not behave like gentlemen at all, jumping on top of women…and when in the boats refusing to return to the disaster site to save those in the water”. (“The American Hero and His Mechanical Bride”).

Contrary to these other alternative interpretations of the Titanic event, the black’s response was however to a large degree a rewriting (signifying) of the mainstream narrative, rather than a simple reinterpretation of the factual happening. Not only was the tone of the plot changed from a regretful event to be mourned to a mechanical accident that merited celebration, also other actors were staged. The main additional actor was Shine who wore the costume of the African(-American) trickster figure who completely overthrew the power relations of the very economic and social structure which in its overconfidence and vanity had given birth to the Titanic.

In a superb metaphorical exercise, black folk lore has thus offered his very own Titanic blockbuster, featuring Shine in the leading role, commenting as few other songs or tales on black reality.

Allow me, by way of closing credits, to quote just one more scene from the plot: “Big man from Wall Street came on second deck.

In his hand he held a book of checks.

He said, “Shine, Shine, if you save poor me,

“Say I’ll make you as rich as any black man can be.”

Shine said: “You don’t like my color and you down on my race,

Get your ass overboard and give these sharks a chase”

********************************************************** Notes

(1) “Elgin Movements” refer to the NATIONAL WATCH COMPANY first incorporated in August 1864, Chicago. Its products were commonly known as ‘Elgins’, and represented about half of the pocket watches in the US. In 1910, it produced its first wrist watch. It was a symbol, at the time, of the nation’s passage from a rural to an urban society, since the watches, once affordable only to the rich, became within the reach of many Americans. So, when String Beans, and later other bluesmen as Robert Johnson and Blind Blake, praised their women for “Elgin movements”, they were talking about the elegance of her body – which, like a watch movement, has curves – as well as how it moved when she walked, or while having sex (see further: (http://www.emusic.com/music-news/spotlight/blueslore-01-elgin-movement/#ixzz1sgZQ878c

(2) Biel (1996) notes that boasting about being nowhere near the scene of a disaster was a tradition in black folk songs. He quotes lyrics in Mississippi in 1909 where somebody asks: “O where were you when the steamer when down, Captain?”, answered: “I was with my honey in the heart of town.” Newman White (1928) suggests that many of the Titanic songs were based on old songs about a long forgotten steamboat wreck on the Mississippi.

(3) Chris Smith (1996) quotes “Hey Shine”, recorded by Delmar Evans, around 1970, with accompaniment by Johnny Otis and his son, Shuggie, under the collective “nom de plume”: “Snatch and the Poontangs” (Kent, KST-657X). Richie Unterberger (allmusic) notes that their “record with sexually explicit and X-rated language () was forward even by the standards of rap music. In that sense, it could be considered a little-discovered antecedent of rap”. The album has, by the way, been reissued as a CD (http://www.amazon.com/Cold-Adults-Johnny-Snatch-Poontangs/dp/B00006IQEQ).

(4) Ironically, an article recently revealed that five prominent feminists were on board the Titanic, and all of them survived bar one –the only male feminist amongst them. (http://theantifeminist.com/five-feminists-on-board-the-titanic/) Further reading

– Chris Smith, The Titanic, a case Study of Religious and Secular Attitudes in African American Song, in: Robert Sacré (ed.), Saints and Sinners, 1996

– Steven Biel, Down with the Old Canoe: a cultural history of the Titanic Disaster, 1997

– Mike Ballantyne, The Titanic and the Blues (EarlyBlues.com)

– Bruce Jackson, Get Your Ass in the Water and Swim like me, 1975/2004

– Steven Biel, Unknown and Unsung: Contested Meanings of the Titanic Disaster, in: Danky & Wiegand: Print Culture in a diverse America, 1998

– Alan Rice, Radical Narratives of the Black Atlantic, 2003

– Leon Dixon, “Shine”, A Folk Narrative, 1992

– Lucy Delap, Thus does man prove his fitness to be the master of things: Shipwrecks and Chivalry in Edwardian Britain (corpus.cam.ac.uk)

– Seth Borenstein, Titanic’s legacy: A fascination with disasters, 2012 (new.yahoo.com)

– Edward Komara, Encyclopedia of the Blues, 2005