Blues from the circus tent

The circus brings to mind feelings of joy, laughter and amazement sprinkled with glitter, and spiced with the smell of sawdust. We see lions, elephants and clowns, and we hear the cries of relief when one trapeze artist catches his partner somersaulting several meters above the floor. It is, however, highly improbable that we will associate the circus with the blues. Yet, the American circus has been one of the media through which rag, jazz and blues have been disseminated in the first decades of the twentieth century. In addition, it was a context for a lively interaction between the folk music on the one hand, and the popular, professional music on the other hand. It was one of the scenes where the cross-pollination took place between the black vernacular sounds echoing on the streets and in juke houses and the notated music distributed by sheets and records.

If you like to find out with me how the circus played this role, join me below for a brief historical trip.

“OLD BET” COMES TO AMERICA

We begin our journey in 1793, when a man called J.B. Rickets, an English equestrian rider, added acrobats, a rope walker and a clown to his act. He established the first circus in Philadelphia. A few years later, a New York citizen by the name of Hackaliah Bailey acquired from his brother, a sea captain, a female African elephant which the latter had laid his hands on at an auction in London. Via the Hudson River, the elephant was transported to the nearest river town to his new owner’s home. From there, Bailey walked the animal, which he had named Old Bet, to his new environment some 56 miles away. The story is that he walked the elephant only by night because he did not want the public to enjoy a “free spectacle”. It was a comprehensible strategy, knowing that the exotic elephant was meant to generate profits by exhibiting it for a small fee.

His initiative turned out to be successful and inspired others to invest in unusual animals for touring exhibitions. Even when dead, the animals remained a profitable project. Stuffed, Old Bet still toured New England during four years.

The rising popularity of the circus was temporarily slowed down by J.B. Rickets’ death in a shipwreck as he headed for England. Old Bet, the elephant, had however firmly kicked the ball, and with it also the concept of the traveling menagerie: touring groups of exotic animals exhibited for a fee. It is estimated that the American public in the 1820′s was entertained by at least 30 traveling menageries. Before the outbreak of the Civil War, the concept of the circus act and the touring animal curiosities were merged, the animals no longer being used only for exhibition purposes, but becoming an integrated part of the larger act.

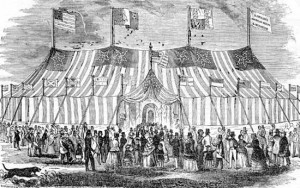

It took only a few more ingredients to lead the circus to the very top of the popular and cheap entertainment at the turn of the century. The transport was the first one. In the 1850s river traveling in general and show-boats in particular were at their height. The first circus show-boat was floated. Not long after, the connection, in 1869, of the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific Rail roads engendered still more opportunities for easier traveling. Already in the circus season of 1872, a train specially designed to move around a circus was put on the rails. Though it remained a dazzling enterprise to tour around the enormous bulk of material, people and animals, the use of specially designed circus train cars significantly increased the degree of mobility, and hence reinforced the spread of the popular entertainment. Contrary to Europe where circuses were managed by families, the American circus was a big business phenomenon, ran by entrepreneurs. The names of Bailey, Ringling and especially Barnum still ring a bell.

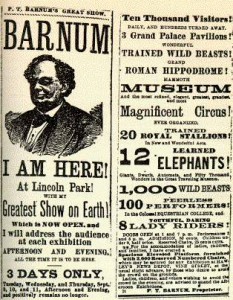

It was the latter who added a second ingredient to render the circus concept even more popular, when in 1841 Barnum purchased a Museum on Broadway in New York City to exhibit half a million (!) natural and artificial curiosities from every corner of the globe. The “freak show” was born. Barnum sensed, correctly, that people wanted to see and pay for the rare and the exotic, not necessarily, in his reasoning, because the natural objects and humans were deformed, but because they were unique. He built his circus empire on this idea. The “Greatest Show on Earth”, destined to bring as much money in the coffer as possible, was put on track.

To give an idea of the magnitude of the enterprise: the “Greatest Show on Earth” rode the rails on 85 rail road cars, employed more than 1,000 people, and consisted of five rings and stages, plus the largest traveling menagerie anywhere.

At the turn-of-the-century, the arrival of a circus in a community was an all-encompassing event, involving the whole local population. The big event was announced well in advance, and accompanied with fancy street parades in the town’s center. Every community had some open space to offer as accommodation, and the circuses were mobile to a degree that they covered the whole nation, from the Deep South to the North, from the East to the West Coast. Labor was cheap, rail roads gained by the transport and street cars brought the happening to the smallest places. Imagine what an event it must have been to host a traveling company of rare and exotic animals and humans, in combination with stunning acrobat acts mingled with comic clown entertainment!

SIDESHOWS OF FREAKS AND BLACKS

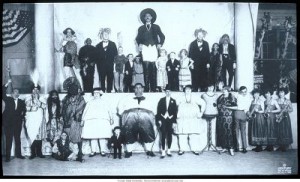

The freak show was an extremely popular ingredient of the circus. The freaks and curiosities were part of what was called, “the side shows”, a secondary production next to the main event and tents, displaying the most exotic and “human oddities” ranging from midgets to giants, and from legless women to three legged boys. Offering a general platform for exhibiting the world’s most exotic attractions in whatever form, the side show was a major component of the general appeal of the circus.

The side show also made the racial discrimination utterly visible in the circus business. The circus production and ownership, though bringing entertainment to a racially mixed audience, was an all-white enterprise which excluded colored artist companies from performing in the big tent, and relegated them to the secondary production. The line between the attraction offered by a black act in the side show, and the mere presence of blacks as an exotic curiosity was, as a matter of fact, in some states not always easy to draw. For many white spectators in the nation, seeing a black person was in itself part of the entertainment. In a 1919 article, “The Freeman” reports: “the difference between an African and an ape was seen in a sideshow cage”, adding in a cool way: “Aside from that, everything was lovely…” (Abbott and Seroff, 2007: 202).

The black companies attached to a circus could consist of two groups. The minstrelsy act, rooted in a show business which dated back already some decades, was the first one, bringing to the secondary stage singers, dancers, comedians and specialty acts. While side shows did not always have a minstrelsy group, the black music band became an indispensable component of it. Its vocals were accompanied with cornets, trombones, baritone harp, trap and bass drums, and occasionally a guitar or banjo, under the direction of a band leader. Although it was not a general rule, many bands included also one or several female black artists. It was furthermore not excluded that “human curiosities” from the freak show leaped over to the black band if they had musical talents. A well-known “freak” attraction who stepped into the musical side show entertainment was Harriet Elizabeth William. She started her career as a “professional midget” when still a young child, known in her early career as, most charmingly, Princess Weenie Wee (or Winnie Wee), “The Animated Chocolate Eclair”. She worked with Barnum & Bailey Circus, among others. In the 1920s, Princess Wee Wee joined a singing-dancing-comedy troupe.

Note that the black band did not replace the white band performing in the main production. When a circus arrived in town, the black band, often seated on a glamorous wagon pulled by a series of horses, was present in the street parade announcing the show, but during the show itself the black musicians were assigned to perform solely in the annexed tent, and featured only occasionally in the after show at the big tent. It was the white band which entertained the audiences in the main tent.

Obviously, the exclusion of black artists from the main circus tent reflected the Jim Crow segregation laws. Yet, in a way, despite their relegation to the side show, the black artists were an essential factor in the whole concept and popularity of the American circus. From this vantage point, the circus situation differed from the vaudeville circuit where the segregation was literally built in concrete, separating the white theater buildings from the black theater houses. A theater owner had a local audience which was more or less steady; a circus entrepreneur, however, was faced with an ever changing audience, as he covered all regions of the nations, and toured in smaller communities, towns and cities with a varying audience mixture. The possibility to employ black artists in an annex show was an ideal way to reconcile different social forces. It combined in a unique way the opposites of segregation and integration. The black artists were at the same time part of the act, and yet clearly separated from the main production. After all, simplifying somewhat the complex reality, the only color that mattered to the circus business entrepreneur was the one of the green back. Assigning the black artist a place along the other exotic items permitted the circus owner to match a real market demand, with a valuable supply, from which ensued for him a very tangible cash profit.

The supply was abundant and rich. There were plenty of black musicians who wanted to capitalize on their talents and start a professional musical career, if it were only to escape from the hardships that were forced on African-Americans in the segregated American economy, and even it implied that they would have to adapt to the expectations of an audience which wanted the blacks to perform as buffoons and coons. Side shows were generally characterized by a steady employment, and the pay check was reliable. Some documents tend even to romanticize the side show employment of blacks, one contemporary comment contending that “W.H. McFarland, who is manager of the side show, is a friend of the colored boys”, and has been said to have “fruitfully assisted in cutting out the segregation idea…” (Abbott & Seroff, 2007: 194-95).

The black musical talent had a lot to offer. The end of the nineteenth century witnessed a culmination of a rich, more than two centuries old tradition of black music that had started with work songs, field hollers and Negro spirituals. Moreover, the clash between the economic booming of the white mainstream society on the one hand, and the propelling back in time of the African-American population to conditions similar to those of the time of bondage, on the other hand, was a circumstance beneficial for a cultural explosion of an essential aspect of the black’s cultural system, even of his total existence: the music. In the words of Sterling Stuckey: “the overthrow of Reconstruction and the forcing of blacks toward slavery at the close of the century were blows to the spiritual life of black people, who rebounded by creating an art that transmutes pain into beauty and gives back to the people what would be taken away – confidence in themselves and the willingness to go on (1987: 288).

In other words, at the turn of the century, there was a rich musical stew being prepared in the plantation communities, streets and juke houses in and outside the red light districts. These were the place where one could hear a creative juggling with existing forms and styles, initially in an amorphous state, but containing already the germs of rag, blues and later jazz. There was a vibrant musical culture in the black working class that experimented with melodies and lyrics. It was a way to confirm its identity and retain its self-respect.

The circus entrepreneur generously tapped from this barrel to meet the ever increasing demands for entertainment, both in the white and the black audience. At the turn-of-the century, the industrialization, urbanization and immigration had changed the social fabric of American society dramatically, and especially in the towns and cities there was an insatiable appetite for entertainment in every form. The former minstrelsy theater was fading in popularity to the benefit of the more sophisticated vaudeville theater. Rag time, largely an offshoot of the coon song, swept over the nation, accompanied by a dance craze – based, by the way, on African syncopation and rhythm – conquering ballrooms and dance halls. Optimism was all over the place. Nothing seemed to challenge the white dream of superiority, infused with a firm belief that reason and technology could solve everything. Economic expansion and political imperialism went hand in hand with cultural enthusiasm. And even if the black population did not share in the fruits of the development, theirs was also a real desire to find ways to spend the evenings and weekends after hard work, especially in the anonymous cities which they had relocated to coming from a rural background.

The popularity of the black bands, attached not only to circuses but also to other touring spectacles as the Wild West Shows, testified to a real demand for up-to-date black vernacular music. The 1910′s were the golden age of the side shows when more and more white circuses engaged black companies to meet the audience’s desire for popular, syncopated music.

BABY SEALS BLUES ARRANGED FOR THE CIRCUS

The black bands played what the audiences expected. Their repertory was thus broad and included any popular tune, covering the whole gamut from light classical work, marches, patriotic airs, and waltzes to rag and coon songs. March music was particularly in vogue at the turn of the century. Most towns, organizations, theaters, and even companies had their own “community” band. Marches filled plenty sheets due to prolific composers like John Philip Sousa. The circus contributed significantly to the popularization of the musical genre of marches.

Coon songs, from the hand of black and white composers, were equally modish. Ernest Hogan’s compositions guaranteed success. Just to refresh the memory: Ernest Hogan was the first African-American entertainer to produce and star in a Broadway show, and was a key figure in the creation and popularization of the ragtime.

The evolution in the side show’s black band repertory obviously mirrored the changing taste of the public. Gradually, march music lost popularity, as did the minstrelsy act of the side show which was replaced by a more up-to-date and varied vaudeville theatre which staged the immensely popular “dance craze” songs. “Walking the dog”, written in 1916 by the African-American Shelton Brooks was one of the big national hits, both for the white and the black audience. The song itself created a dance sensation, and has probably helped to pave the way for the introduction of jazz to the mainstream popular culture.

During the 1910’s, also the notated blues came to occupy an ever increasing part of the repertory of the black side show bands. The “Freeman” journal from November 9, 1912 reports on a band arrangement of “Baby Seals Blues”, one of the first published blues songs, under its heading: “News from Yankee Robinson’s Annex Band”: “Prof. John Eason, leader and manager. The bunch sends regards to all in and out of the profession. Mr. Frank Terry is still with us and has just finished a band arrangement of Baby Seals’ “Blues”, and is making a daily hit with it.” (The Freeman, 9/9/1912: 6). This is probably the start of the blues in the circus context. It would be followed by compositions of W.C. Handy, Chris Smith and others who provided the material for the black show bands.

As the public demanded more blues, so did the bands include more and more blues songs in their repertory up to the point that “by the middle of the decade, blues had become a special attraction that sustained the popularity of African-American entertainers under the side show tent.” (Abbott & Seroff, 2007: 177). The story has been noted of a circus giving a charitable performance in 1916 within the walls of the Michigan City jail, where the loudest applause was reserved for the elephant act and for the annex band “playing the blues”.

It is no wonder that the black bands of the side shows integrated more and more songs in their repertory that are in present terms referred to as jazz and blues. The annex bands stood in the first line when it came to feel what the audiences liked. They were antennas by excellence, both receiving and sending signals. They helped, through their wide geographical coverage, to spread the notated music, published on sheets. The popular published music interacted continuously and spontaneously with the folk music, infusing each other with new tunes and lyrics. The professional and the non-professional met and exchanged musical ideas. Musical interaction was common, often in the form of local bands temporarily teaming up in the streets with the visiting black bands, to the greatest pleasure of the local populace which received a free show.

Visiting a town with a black vaudeville theater was for the side show band also the occasion to spend some evenings on the local stage, and for some bands this ignited the start of touring the vaudeville circuit, leaving temporarily or definitely the circus business. The experience built up in the sideshow of the circus was capitalized for a career in the vaudeville circuit.

Osmosis was a feature of the different black musical scenes, extending later also to the recording business. The career of Lizzie “Creole Songbird” Miles is a nice illustration of it. Lizzie Miles spent her formative years in 1914-1918 touring the country with her husband who was the bandleader in a circus side show annex company. In 1922, she made her first phonograph recordings in New York of blues songs. Though Lizzie Miles did not like to be referred to as a ‘blues singer’, the testimony of her husband of a performance in Pennsylvania in 1914 left little doubt with regard to the nature of her musical performance: “Our band and minstrels () is the feature of the Annex, featuring principally the latest rags and popular airs. And who says that the ‘Blues’ won’t go in this section. It goes bigger here than it does in [Alabama], as they follow the big band wagon in vast throngs, yelling can be constantly heard, ‘Give us some more of yer Memphis Blues…” (Abbott and Seroff, 2007: 179). For those interested: the LP “Moans and blues”, on the Cook Records Label, brings a most enjoyable collection of Lizzie Miles’ classic blues.

THE SIDE SHOW: A ROLLING CONSERVATORY

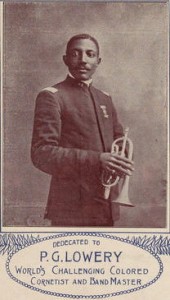

Of all the side show black band leaders, the name that features most prominently is that of P.G. Lowery, whose talent and skills were a major catalyst of the black side show annex act. A professional association with him was then the best guarantee of success, and those who had the chance to work or have worked with him could proudly bear the medal of belonging to the “Lowery school.” His band was considered to be the nobility of circus side show annex entertainers. His organization was a “rolling conservatory”; it was the “School of Music”.

P. G. Lowery, born around 1870, in Kansas, as the youngest of a highly musical family, was a cornet virtuoso, but above all an entrepreneur and professional who would in his career teach, train, manage and employ hundreds of musicians, demanding only the best from them (Clifford Edward Watkins, 2003). He is credited with being the first African-American musician who put his own vaudeville act in a circus. In 1906 he created his own “Progressive Musical Enterprise”. Four years later, The P. G. Lowery & Morgan Minstrels toured the United States. Thanks to his efforts, there were by 1910 “no less than fourteen white tents giving employment to big colored companies” (The Freeman, 9 July 1910).

He performed and led groups on vaudeville and for circuses for thirty more years. In 1919, Lowery was hired to conduct his own band for the freshly merged Ringling Brothers & Barnum and Bailey Circus, and remained with the circus until 1931. Before his death in 1942, he would travel with different other circuses.

Lowery’s company, like the others, included the blues in its repertory. In 1915, a critic reports on an Atlanta theater show where a rendering of “classics and some real hot rags” was followed by “the(ir) regular closing, a medley, call(ing) for an encore which they answered with the blues.” (Abbott and Seroff, 2007: 198). A critic from the same journal reported in 1916 that Lowery’s band was the best formation of any band on the road. The band was featuring Handy’s “St. Louis Blues.” (idem: 200).

SUFFERING FROM THE WAR AND THE INFLUENZA

The year 1918 was a dramatic one, not only for the nation, but also for the circus and its side show. After more than two and a half years, President Woodrow Wilson could no longer defend the neutral position of America in the World War I. The organized entertainment sector, and particularly the road entertainment, felt the impact immediately both as a result of the draft, which took a heavy toll on musicians and minstrels, and as a consequence of the war claim on the means of transportation. The trains were to move troops and military supplies instead of entertaining shows. The railway traveling hampered, the mobility of the circus was equally made very difficult.

In addition, the Spanish influenza, which spread was reinforced by military convoys, hit unimaginably hard. Between its sudden outbreak in 1918 and its equally sudden halt in 1919, more than 650,000 Americans died of influenza and pneumonia. It killed far more Americans than soldiers killed in combat in World War I, World War II, Korea, and Vietnam combined. Major American cities were quarantined, excluding any moving in or out. Needless to say that the circuses and side shows suffered severe financial and human losses, and many companies had to close down.

By then, Jazz and Blues were firmly on the program of the black side show bands, which would continue to tour until the second half of the 1940’s. However, by the end of the 1910’s they had already put their indelible prints on the path of the dissemination of the jazz and blues in the popular culture. In the words of Abbott and Lynn: “By this time the United States had experienced a generous exposure to jazz and blues in the somewhat indecorous context of the side-show annex” (202). In August 1920, Mamie Smith would enter the studio and her waxed output would add a further major medium to the spread of the blues, but let us not forget that the blues was then already definitely a part of the popular culture.

________________________________________

Acknowledgements

The credits for this essay go completely to Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff whose invaluable research in the historical archives have permitted to unearth the role of the circus side show in the spread of the popular music (Ragged but Right, 2007)

_______________________________

Reading:

– http://www.history-magazine.com/circuses.html

– http://www.ushistory.org/us/index.asp

– http://jass.com/sheltonbrooks/brooks.html

– http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=FIkAGs9z2eEC&dat=19121109&printsec=frontpage&hl=en

– http://www.angelfire.com/music2/thecornetcompendium/well-known_soloists_8.html

– Errol Hill, James Vernon Hatch, A History of African American Theatre, 2004

– Clifford Edward Watkins, Showman: The Life and Music of Perry George Lowery, 2003