Bob Dylan in His Gospel Time: Trouble No More — The Bootleg Series Vol. 13/1979-1981

On a cold November night in 1998, I went with two friends to hear Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell at University of Maryland’s Cole Field House. Mitchell strutted on stage by herself, smoking and toting an acoustic guitar. Stowing her cigarette somewhere in the frettings, she let loose with “Big Yellow Taxi” and played a glorious set that ended with “Woodstock.” After a long break, during which we shivered and jumped around to stay warm, the lights dimmed and Al Santos’s voice sounded out, directing us to welcome Columbia recording artist Bob Dylan. Dylan, already at his mic, grinned wide as he launched into “Gotta Serve Somebody.” The crowd laughed at the way this sounded like a zing directed at his longtime label, and perhaps also at himself. However, it turned out to be one of the best performances of the song I’d ever heard. When Dylan sings “Gotta Serve Somebody,” I thought, he’s not joking around.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ot7lyo-YgC0

“Slow Train,” London, June 1981

He might have (indeed, did) won a Grammy for best male rock vocal performance in 1979 with this B-side single, steeped in the Southern heat and camp-meeting feels of the Alabama where it was recorded, but in 2013 Rolling Stone listed it among Dylan’s ten worst songs. What happened between 1979 and 2013? A lot of water, and other stuff too, under the bridge. Dylan’s “Gospel years” of 1979-1981 (utterly incorrectly dated; more on this anon) gave way to the allegedly secular Infidels, the allegedly rocking Down In The Groove, and eventually triumphs like Oh Mercy, Love and Theft, and Modern Times.

The only child of an ordained Baptist minister, I always had understood that choice between the devil and the Lord in “Gotta Serve Somebody,” and also the qualifying “may be”s. Those records in the wake of Dylan’s Gospel years show him, critics have claimed, out of what they call his “religious phase,” as if he is a moon rather than a man. Being saved isn’t a phase, friends. It’s a part of you ever after, world without end, amen.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FNlZXwyYoao

“Solid Rock,” London, June 1981

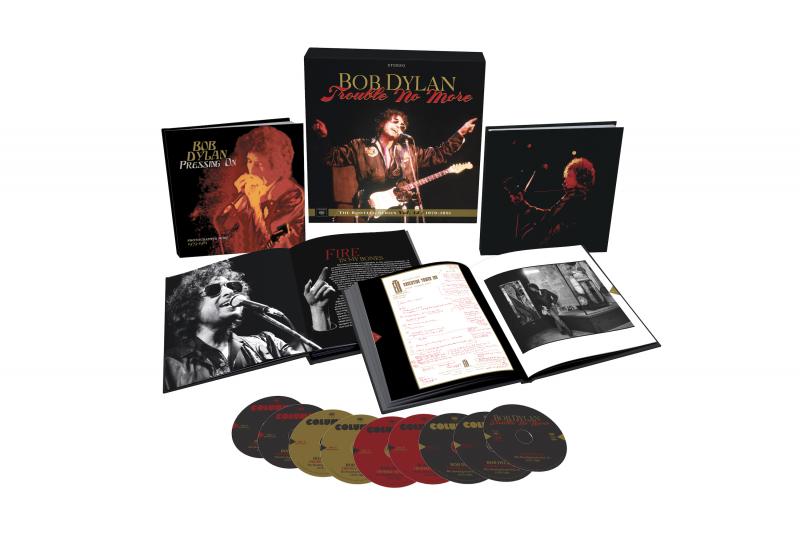

The newest box set in the ongoing Bootleg Series, Trouble No More — The Bootleg Series No. 13 / 1979-1981, spares you nothing in examining this point in Dylan’s life and professional career. Many stage performances of his “religious songs” flesh out most of the body of eight CDs, along with a DVD of Trouble No More: A Musical Film, reviewed here, that includes stage and rehearsal performances from 1979-1981, as well as entirely new footage with an actor as a preacher, and shot in a church.

* * *

San Francisco, November 11, 1979. Dylan introduces a song he will sing in almost every show. (Almost. His set lists were not yet set in stone.) “This is called ‘Slow Train Comin’. It’s been comin’ a long time, and it’s picking up speed.” The sound on Trouble No More is astounding, start to close, beautifully made at the time by the top-tier band, and remastered by Steve Addabo, Chris Shaw and Mark Wilder (Jeff Rosen, Steve Berkowitz and Gregg Geller are the producers). With only slight variation, and fully covered in the extensive liner notes, the band consists of Dylan on vocals, keyboards, harmonica and guitar; Fred Tackett on guitar; Tim Drummond on bass; Jim Keltner on drums; Dewey Lindon “Spooner” Oldham on keyboards; and Terry Young on piano and vocals.

The chorus, or to name them more properly, choir featured some of the best-known women singing gospel — or any other kind — of music then. Clydie King made her first recording at thirteen, and had sung with the Rolling Stones, Steely Dan, Lynyrd Skynyrd and B.B. King, among others, before joining Dylan’s band. MonaLisa Young (whose husband, Terry, was also on the “Gospel tour”) had sung professionally since she was 16 in vast churches and on opera stages, trained by her mezzo-soprano mother Catherine Ballinger. Regina McCrary, daughter of a singing minister (and now both herself), regularly opened the shows. McCrary is true gospel royalty; her father, Reverend Sam McCrary, was a founding member of the Fairfield Four. Mary Elizabeth Bridges and Gwen Evans round out the group of women who are far more integral to these shows to be collectively dispatched as “backup singers.” Other musicians join the rolling revival on stage and in the studio: Carolyn Dennis, Benmont Tench, Willie Smith, Danny Kortchmar, Madelyn Quebec, Mark Knopfler, Helena Springs.

“When You Gonna Wake Up,” Oslo, July 1981

Trouble No More begins with that “Slow Train” in San Francisco, 1979, and ends in Earl’s Court, London, in 1981. Crowdpleasing hits have reappeared — “Mr. Tambourine Man,” “Blowin’ In The Wind,” “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” — but “Slow Train” still starts the show. In the course of making your way through, you hear Dylan’s devotional songs on repeat, just the way hymns are in church. The question song “Are You Ready?”, “Saved,” “Ain’t Gonna Go To Hell For Anybody,” “Solid Rock,” and the anthem “Pressing On” are, along with “Slow Train” and “Gotta Serve Somebody,” available in various versions on the eight discs. The previously unreleased “Help Me Understand” is a sad song about divorce and its effect on a child, little Sue. “Ain’t No Man Righteous, Not No One” is a rollicking condemnation and revels in rhymes like “hypocrite” and “opposite.” “City of Gold,” slow and full of a mournful, then joyful organ playing, finds salvation based in both the words of the Bible and of Shakespeare:

There is a city of love

Far from this world, stuff dreams are made of….

New lyrics are in the songs you thought you knew. I’ve been listening to and loving “Caribbean Wind” for years, but was blindsided by “I was only paying attention like a rattlesnake does when he’s hearing footsteps trampling on the flowers.”

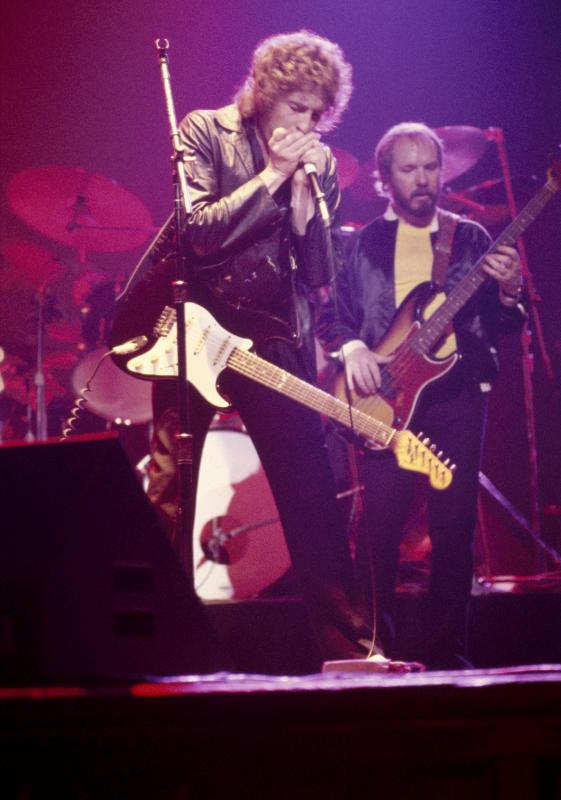

Dylan, with Tim Drummond, by Lawrence Kirsch © Sony Music Entertainment

The essays included with Trouble No More inform, complement, complicate, and supply context, as well as personal opinion. Ben Rollins finds in Dylan’s decision to write, perform, and record his own gospel music one of the most controversial “twists and turns” in a winding career. That Rollins has quoted the beginning of The Odyssey here is both clever and apt: “Sing to me of the man, muse / The man of twists and turns.” He is right, too, to call the “Gospel tour” both “a true revival meeting” and “more of a revue, actually.” I’ve been to both. Rob Bowman’s track-by-track listing is expert, replete with detail and reason, and essential. Amanda Petrusich walks us swiftly and skillfully through the ’70s, that “Me Decade” in which America lost its war in Vietnam, its faith in a president, and turned in search of something, anything to believe in again. Her Dylan seeks “a way forward,” hand in hand with the remorseful times. And Penn Jillette, in a searingly personal essay that is a thousand percent right, and righteous, understands the music on Trouble No More in a way that also understands something integral about Dylan:

Common wisdom is that Dylan went back to being a secular song writer after this period, but that’s a lie. The truth is Bob Dylan never was and never will be a secular song writer: “God said to Abraham kill me a son” – is not “Fly Robin Fly.” “I can hear a sweet voice gently calling, must be the mother of our Lord.” “I’m sworn to uphold the laws of God.” And “Narrow Way” is more about Jesus’s “narrow gate” than an answer song to Sir Mix-a-Lot.

“Making a Liar Out of Me,” previously unreleased, 1980

Amen, Penn. Dylan never was, and never will be, a secular songwriter. The songs on that trinity of “saved” albums — Slow Train Coming, Saved, and Shot of Love — and the songs of his “Gospel Tour,” both familiar and unheard until now, are the portion of Dylan’s spiritual songs that lend themselves to easy definition and categorization. But as Regina McCrary put it, years later, in an interview with Scott Mitchell for On The Tracks,

what I saw and who I saw was a man. A man who had an awesome gift from God, even down to his other music. When I got still and I listened to the words to some of the songs that he wrote before I joined him, it was awesome. God has been using him and his songs and his lyrics for a long time. And he’s been speaking out against the wrong and standing up for the right for a very, very long time. So when he did Slow Train Comin’, Saved, and Shot Of Love he only brought everything that he’s been doing to a full circle to let people know that he’s been serving a live and a living God, all his life.

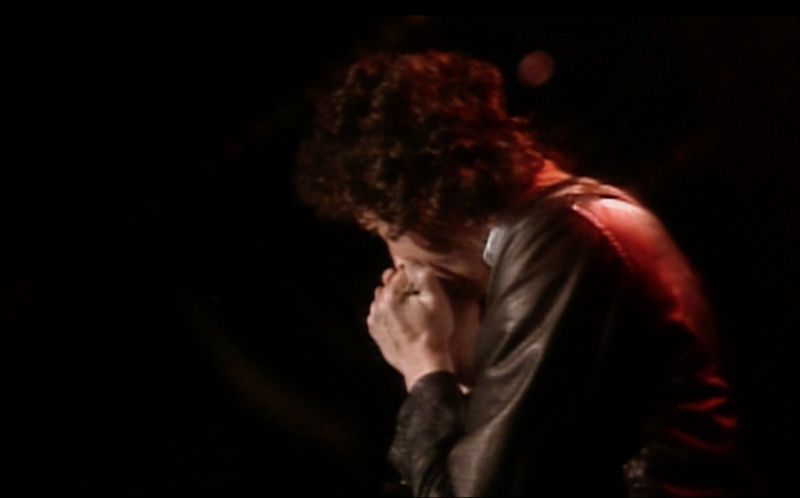

Dylan and his harmonica, from Trouble No More: A Musical Film

*

In his songs today, in his releases of albums, in his live performances, Dylan has given up nothing. He repeats his past in that full circle that McCrary describes, adding to it, and filling it, with what has come since. Encompassed tonight by a new venue and a new crowd, he and his band, and Mavis Staples — a beloved old friend, with her God-given voice for the ages — are already pressing on.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lhJaENjDEME

“Every Grain of Sand,” previously unreleased

all images courtesy of and © Sony Music Entertainment 2017