Bob Dylan’s Three “Blood On The Tracks” Notebooks: Not Just Red

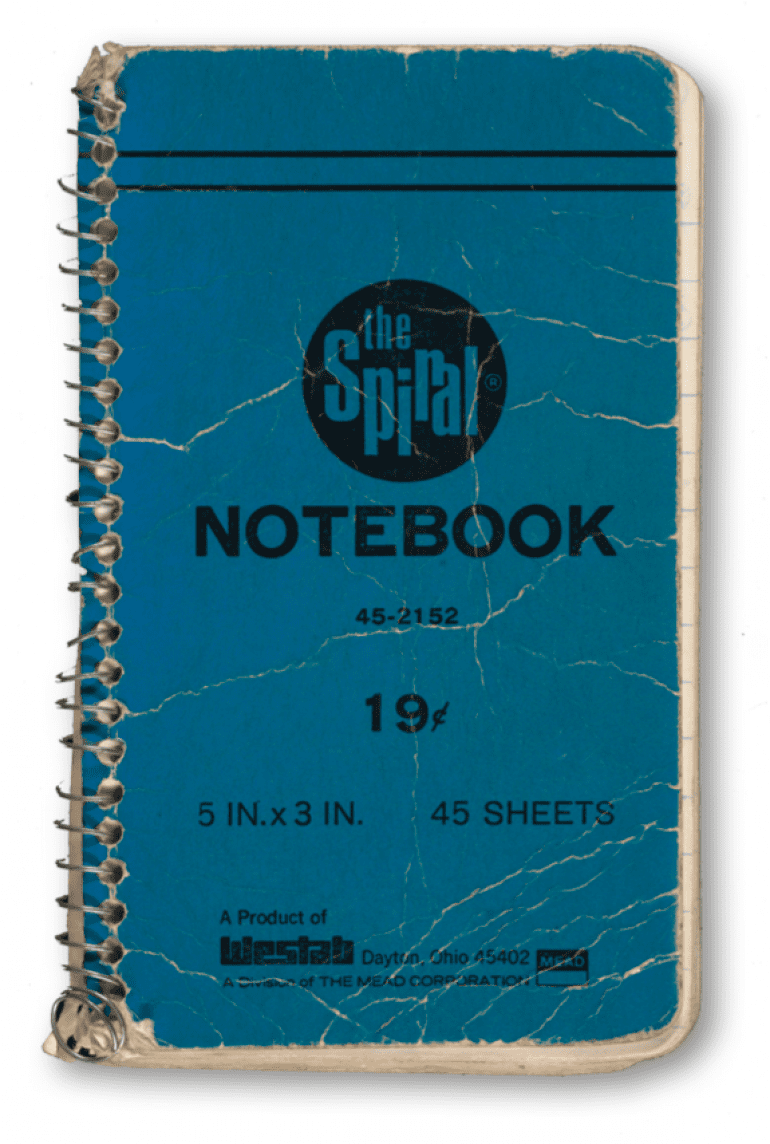

The Blue Notebook, © Ram's Horn Music 1974; 2001 and courtesy of The Bob Dylan Archive® Collections, Tulsa, OK.

For decades, fans of Bob Dylan have known about “The Red Notebook,” in which he drafted the songs for his 1975 album Blood On The Tracks. Seventeen years ago, Marc Jacobson in Rolling Stonecalled The Red Notebook “the Maltese Falcon of Dylanology, the stuff dreams and nightmares were made of.” Clinton Heylin discussed it in his revised Dylan biography Behind the Shades Revisited (2001), specifying a spiral notebook in which 17 songs were written during the summer of 1974. Sean Wilentz amplified on this in Bob Dylan In America(2008): “That summer of 1974, working mainly in a house around back on a farm he had purchased in Minnesota along the Crow River … Dylan pored over a small red notebook, writing lyrics for a new album that would capture the wounds, scars, and sorrowed wisdom of love.” In The Dylanologists: Adventures in the Land of Bob (2014), David Kinney tells the story of a fan named Michelle Engert who was permitted to read and transcribe The Red Notebook in 1994, before collector George Hecksher housed it in the J.P. Morgan Library and Museum in New York City.

The Red Notebook has its very own pages, and threads, at ExpectingRain.com and rec.music.Dylan, and is hailed as a one-of-a-kind icon by prominent Dylanologists and music critics still. Jeff Slate, author of album notes for the new Dylan “official bootleg” and box set More Blood, More Tracks: The Bootleg Series Vol. 14 , wrote in a fascinating recent essay on the evolution of “Tangled Up In Blue”about “perusing Dylan’s fabled ‘red notebook,’ in which he’d written the lyrics to the ten songs on ‘Blood On The Tracks’ in his tiny, precise scrawl.” Alex Ross, covering More Blood, More Tracks for The New Yorker in November, similarly spoke of The Red Notebook as a singular grail. He discusses some of the drafts in The Red Notebook in detail, which one can now do, as the notebook has been reproduced in full — almost — as a part of the deluxe MBMT box set. A photographic goof meant that four pages were left out; BobDylan.com swiftly discovered the error and supplied the pages online.

The Red Notebook is a Maltese Falcon no longer. Its pages, bearing what seem to be nearly finished songs (if this can be said of any Dylan song; he continues to revise some of his best-known ones today, in performance and in written versions) and abandoned drafts, can be read and studied by anyone who has bought the reproduction, and who has very good eyesight or a strong magnifying glass. However, we have known for the past few years that two other notebooks in which Dylan drafted the Blood On The Tracks songs exist. From now on, we shouldn’t refer to “the” notebook, as if there could be only one for all that art, as if Dylan did all his drafting in near-done form.

When in 2016 The New York Times reported on the Bob Dylan Archive and its impending arrival at the University of Tulsa, Oklahoma, Ben Sisario announced in his lede that The Red Notebook “is part of a trinity. Sitting in climate-controlled storage in a museum here are two more ‘Blood on the Tracks’ notebooks — unknown to anyone outside of Mr. Dylan’s closest circle — whose pages of microscopic script reveal even more about how Mr. Dylan wrote some of his most famous songs.” The Times even published a photograph of the two notebooks side by side: one is spread open at two draft pages of, primarily, “Tangled Up In Blue”; while the other, its cover gone, is styled as a diary beginning Oct. 27th with the entries “bottle with cork / Volvo / Richard’s car” and the “Tangled Up”-related phrase “2 miles off Delacroix” at the top.

Last fall, I reviewed these other two notebooks and wrote about them. Hot Press, for which I’ve written about music and movies since 2012, made this first look a cover story in the print version of their 2019 Hot Press Annual. Here’s the scoop on the Tulsa notebooks. One is coverless, though the ghost of a red-orange edge remains trapped beneath the wire. Very battered and fragile, it is a working book of lyrics but also of lists of art supplies, thoughts, telephone numbers, observations, addresses, pithy notate bene, the rare occasional doodle, and reminders of various kinds. The other is pale marine blue, and is a gold mine, a quarry, a map of creating, a veritable trove of compositional ferment. Taken together, they show Dylan’s drafting process and artistic creation in a richness and detail that it has not been possible to chart until now.

The two Tulsa notebooks, catalogued simply as Notebook 5 (the coverless one) and Notebook 6 (the blue one), are undated, with few clues as to exactly when or where they were written. Almost every page of them is heavily revised, with sometimes scarcely legible scribbles above, below, and in the margins, next to the lines in the middle of pages that were presumably written first. Dylan returns to everything, writing up the sides and adding words in parentheses, or not, between the lines. He uses plain black or blue ballpoint most often, with corrections and changes in the same color. Sometimes he uses a pencil, and the legibility worsens. His words, phrases, parentheticals spill out in the same thought-go, or were maybe added an hour, a day, or months later. There is no way of telling, other than to ask him. The extent of his revising is staggering; one thing pouring out of his songwriting is the perfectionism. Even his fellow Nobel laureate W.B. Yeats’ convoluted drafts are not so ubiquitously utterly changed.

In places Dylan’s tiny printing is as tidy as if he had already planned the lines in his head, while in others he veers into a swifter, far harder-to-decipher semi-cursive. What is clear, however, is the astonishing fact that Dylan was conceiving and composing multiple songs at the same time — in the same breath, same thought. In many instances, he does not separate songs, or will do so rudimentarily, with a dash or in a parallel column on the same page. He veers from “Simple Twist of Fate” (a song initially called “Snowbound,” then “4th Street Affair”) to “Tangled Up In Blue” (also titled “Blue Carnation I” and “Dusty-Blues”) to “Meet Me In the Morning” and back again. Everything is happening in his head at once.

Even the moments Dylan abandons are golden — and many resonate today, as the best of verses will. I could not get past one lone verse:

Perhaps you’ve seen me walking

On the highway in yr mind

Had some big ambitions

But they all broke like glass

Always done my duty

And tried to be kind

I couldn’t stop the progress

Of a nation going blind

A deep dive to the bottom and back up again, into all three of Dylan’s Blood On The Tracks notebooks, would be a book. The glimpses I’ve given are intended to make you glad that you don’t have to talk only about The Red Notebook any more — it has kin, and they all provide precious documentation of both the fertile welter and the professional perfectionism of Dylan’s creative process.

Image and previously unreleased material copyright © 1974 Ram’s Horn Music. Renewed, 2002 Ram’s Horn Music. Additional lyrics, Copyright © 2018 Ram’s Horn Music. Courtesy of THE BOB DYLAN ARCHIVE® Collections, Tulsa, OK.