Bobby Hutcherson Brought Spiritual Questing and Down-home Allure to the Vibes

On another sultry but beautiful day yesterday, I had to get away from the computer and outside in the afternoon. So I went out to nearby Kern Park and shot some baskets and, because I was the only one with a ball, I attracted a few other guys and we ended up getting into a game of hustle that included one 6 foot 2 dude who could dunk the ball, another built like a linebacker, and an 11-year-old who consistently sunk high school three-pointers from beyond the top of the key! It was great fun and then I did some grocery shopping in my sweaty shirt, and when I came home I did not want to go back to the computer or Facebook.

So I didn’t learn about vibes and marimba player Bobby Hutcherson’s death until I peeked at Facebook at about 10 PM and noticed Howard Mandel’s recommendations for listening to Hutcherson albums. My heart sank because I figured he’d been prompted by Hutcherson dying. I scrolled down and found a few more posted tributes and then Nate Chinen’s New York Times obit. The great musician had died Monday at age 75, at his home in California, after years of struggling with emphysema.

Although I studied piano, Hutcherson was the guy who, more than anyone, had me fantasizing about playing the vibes, from time to time.

Seeing the obit, I immediately thought back to one of the very first phone interviews I ever did when I began covering jazz for The Milwaukee Journal in the fall of 1979. It was with Bobby Hutcherson, who was to be performing at the Milwaukee Jazz Gallery, and I still have the cassette recording of the interview because he so impressed me when I hung up the phone. I thought to myself, this was one of the most musically dedicated and spiritual persons I have ever spoken to.

Part of that openness to the spiritual or psychic or the subconscious arose in an anecdote he related to me about the great wind multi-instrumentalist, Eric Dolphy, with whom he had spent time playing and recording with in the 1960s before Dolphy’s premature death.

Hutcherson recalled: “Eric used to call me up, maybe 4 o’clock in the morning, tell me his dreams. He’d say,’ Bobby, write this down.’ Things like, ‘one, six, eight, 17.’ You know, numbers and letters. He dreamt these things as if they might mean something, like intervals or scales or chords.

“The next morning he met me at my house and we would try to figure out what it meant, and try to play something from that dream.”

Earlier in the interview, Hutcherson also said: “I want to play some tunes that people can hum, you know, just as long as I can still make a living being true to myself and giving something to people. They can respect you for digging into the music. Like there’s still some hope in this or it lasts, because it’s for real. It helps to destroy some of the plasticity of this world.”

You sensed in the man and his playing the desire to create beauty but also to press ahead with an insistent sense of what was musically possible and that might change things for the better, at least a bit.

I was also fortunate to have just heard, in person at the Jazz Gallery, Hutcherson’s greatest inspiration vibist Milt Jackson, a few weeks before I interviewed Hutcherson. And there was no doubt that the great Jackson showed that he was the master of both the blues as expressed in through this ostensibly non-blues-friendly instrument, and the king of vibes swinging, against and around the rhythm.

Then Hutcherson played Milwaukee in late October, 1979, and looking back at my review (in the anthology of Milwaukee Jazz Gallery press coverage published by the Riverwest Artists Association) I noted an affinity with another great jazz musician that he would collaborate with quite often, pianist McCoy Tyner. The review headline is “Jazz Storm has Serene Center.” I wrote: “The effect is precisely that rare sense of drama that can be found these days in the group of McCoy Tyner, but with no saxophone for easy ascent. Hutcherson struggles and thrashes, reaching, reaching. But he never quite gets to the note, even if you heard it.” That was the sense of purpose and ever-driving momentum and ultimately questing that gave a backbone to Bobby Hutcherson’s stylistic beauty and spiritual balance.

Just a few days before his death, I had been thinking about Hutcherson and had pulled out a few of his CDs to listen to, including one of his later and lesser-known Blue Note albums called Patterns (1968), which is marvelous and a bit challenging with James Spaulding’s bracing alto. But there’s also plenty of color, texture and pattern with Spaulding’s flute and, of course, Hutcherson’s vibes and Joe Chambers’s artful percussion play.

Here is Hutcherson’s stately but swinging title tune Patterns.

There are a number of other excellent Hutcherson albums including his heady Blue Note debut Dialogue with pianist Andrew Hill and the great Madison, Wisconsin bassist Richard Davis, recorded shortly after Hutcherson and Davis had collaborated with Eric Dolphy on his masterwork album Out to Lunch. There is also the meaty Stick Up! with Tyner and saxophonist Joe Henderson, and the ambitious nine-musician album Spiral.

Hutcherson’s auspicious debut on Blue Note, “Dialogue.” diskunion.net

By contrast, also recall Hutcherson playing on guitarist Grant Green’s languid soul-jazz classic Idle Moments.

Then there are two albums that feature Hutcherson’s warmly alluring marimba as well: Components from 1965 with “Little B’s Poem” — “the lilting modern waltz written for his son Barry,” as Chinen notes, and Hutcherson’s best-known tune.

Another notable marimba-colored album is Blue Note’s 1966 Happenings, a quartet date with Herbie Hancock that includes Hutcherson’s gorgeous meditation “Bouquet” and a superb reading of Hancock’s modern standard “Maiden Voyage” and the weirdly witty free-jazz piece “The Omen.”

Also consider the album Oblique, another quartet with Hancock, which includes the pianist’s theme from the classic French new wave film Blow Up. The theme’s intoxicatingly catchy chordal vamp can get you dancing but also carry you someplace.

My most specific appreciation, however, will be reconsidering one of Hutcherson’s most personal recordings (on Contemporary/OJC) which I just listened to again. It’s called Solo/Quartet recorded in 1982 with McCoy Tyner, Herbie Lewis and Billy Higgins.

“Solo/Quartet” is one of Hutcherson’s most personal projects. allmusic.com

It opens with three pieces that Hutcherson recorded solo, with multi-track overlays. The first is “Gotcha,” wherein the marimba takes the improvised solo, conveying the intense repetitive patterns of Hutcherson’s kind of the blues feel, but also a sense of spiritual wonder. He’s “gotcha” — caught you in the resounding percussive melodic web layered here by multi-tracking. It’s simple but complex in its charms.

Then comes “For You, Mom and Dad,” a humble but radiant lyrical theme with the sort of resonating and questing peak notes that were part of Hutcherson’s characteristic open-mindedness, his sense of possibility. Again his marimba takes the improv lead and its warm, woody wit is elevated into stunning arpeggios circling to a climactic high note, and then he sustains intensity while revisiting the theme with tubular bells backing it. Hutcherson had managed with nothing but the striking of metal and wood instruments to create a spiritual vibe that is nevertheless, down-to-earth enough to be understood as a song tribute to his parents. As if to say, look, mom and dad. This is what I’ve been able to create partly because you were there, and supported me all the way. Even though his dad wanted him to be a bricklayer.

I love Chinen’s story about Hutcherson driving a cab during hard times in New York with his vibraphone in the taxi trunk.

What the wouldn’t-be bricklayer built was a new way for the vibraphone, in a mode different from what his great contemporary Gary Burton did with his four-hammer virtuosity.

The following solo tune on Solo/Quartet “The Ice Cream Man,” is another example of this musician’s balance between playful earthiness and psychic wonder. He’s clearly mimicking some of the sounds recalled from the bell-ringing, neighborhood-trolling ice cream trucks of his youth, but the sound of the note decay of the vibraphone is perhaps the key to the piece. This sostenuto effect opens the mind up, even as the melodic and rhythmic patterns beneath it engage you. The repeated playing of the theme is not tiresome; rather something you tend to savor, like every lick of an ice cream bar on a hot summer day. It keeps you rolling with the truck’s chiming melody, and in Hutcherson’s aura. The total effect is enchanting and transporting and yet he’s taking us back to familiar experience, like the best memoirists.

Hutcherson does this all by himself because his own personal life and experience is being relived and transmuted into a vivid almost cinematic environment. I know of no vibist who has accomplished so much all by himself on a recording.

The album’s last three tunes re-unite the Stick-Up! rhythm section, the great McCoy Tyner on piano, Hutcherson’s long-time friend, bassist Herbie Lewis, and the wondrously dancing drummer Billy Higgins.

“La Alhambra” is a Hutcherson piece of brief ascending and descending rhythmic phrases with very shapely chord changes implying a classic Latin rhythm, with bass and drums percolating beneath. Tyner’s astonishing, muscular, supercharged energy comes cascading out of the chute, but he fully honors spirit of his friend’s composition with its Latin rhythmic allusions.

Solo/Quartet is also remarkable because, as producer John Koenig explains in his liner notes, “during the album’s planning stages Bobby had an almost tragic mishap with a power lawn mower in which he sustained an injury to the index finger of his right hand which nearly ended his career.”

During this convalescence, Hutcherson had time to reflect on what he really wanted to say in such a personal project, and thus the true quality and depth of Solo/Quartet was born.

The next two tunes are two of the finest old standards in the repertoire book, both soulful vehicles that singers usually make the best of. But Hutcherson feels rightly that his vibes can do songful justice to both “Old Devil Moon” and “My Foolish Heart.” And he’s absolutely right.

Again, it is his combination of swirling pattern-making and eloquent melodic phrasing that lifts the songs as high as an old devil moon and as deep as a heart, foolish though it may be.

The album closes with Hutcherson’s “Messina,” a characteristic melding of subtlety and whirling, surfing rhythmic momentum, the sort of tune he might’ve dreamed up watching the powerful ebb and flow of the Pacific Ocean near the home he built in the coastal town of Montara, California, which is his native state.

Solo/Quartet is such a marvelous record also because Tyner is a very kindred musician and this quartet swings deeply in a very modern ways, shifting and sifting through phrasing implied by the melodic changes. Clearly Hutcherson learned a lot from Milt Jackson about swinging, then found his own way to do it.

In 1986, Hutcherson also has an interesting brief apprearance in a wonderful feature film Round Midnight by Bertrand Tavernier which stars saxophonist Dexter Gordon as a dying jazz great in Paris. Hutcherson plays a sort of expatriate but down-home cooking connoisseur in an amusing role. Yet it fits in with the man’s aesthetic for finding the good, beautiful and soulful — even in the most unlikely or displaced of places.

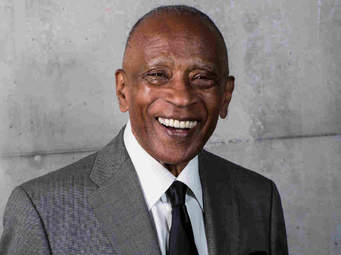

Bobby Hutcherson. Courtesy media.npr.org

Now, since the passing of other great California modern jazz giants like saxophonists Art Pepper and Joe Henderson, big-band leader and composer Gerald Wilson, and now Hutcherson, the historic role of the West Coast, in post-bop and modern jazz is beginning to become clearer, set against the somewhat East Coast-centric focus of modern jazz. West Coast cool jazz was a contrast to East Coast energy, but as a summation of the region the label always fell short. All these deceased musicians, and others like Horace Tapscott, Arthur Blythe, and The Bobby Bradford-John Carter Quartet embodied West Coast creative fire, as finely calibrated as theirs could be.

The SFJAZZ Collective, with Hutcherson-influenced vibist Warren Wolf, exemplifies that West Coast modernism today, as both a repertory band and a vehicle for its members’ original compositions. Don’t be surprised if they honor Hutcherson with a recording of his compositions.

Let us always think in such larger terms when we consider the qualities of such a wide and deep art form as jazz, and the great musicians who brought contrasting and complementary sensibilities to advancing it.

Hutcherson’s long, gleaming vibes tones will always radiate, like a Pacific lighthouse beacon in the darkness, through the music’s history.