Breakfast In Nudie Suits: Ian Dunlop’s Time Machine (Book Review)

“We find after years of struggle that we do not take a trip a trip takes us.”

― John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley: In Search of America

Some have compared Ian Dunlop’s tale of the long road back East after escaping the nightmares of L.A. in the mid-1960s to Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. I can see why but, to me, it’s closer to two other novels.

I remember as a young kid reading Steinbeck’s tale of wandering America as an older writer with his career behind him. Travels with Charley was the first time I got a real sense of my country, the good and the bad of it. I somewhat recognized it as my family would drive from Buffalo, New York, to northern Wisconsin every summer, and most of the road back then was not yet Interstate with its homogenized landscape.

I first heard Gram Parsons about the time I was reading Nabokov’s Lolita for a class in college. I’ve read it at least four times since. They say that Lolita was about Nabokov’s love affair with America, and I believe that’s true. In my mind no one has painted a better picture of those long-gone highways than in this oft-maligned novel, with the exception of the master American painter Edward Hopper.

Also, about that time, Dennis Hopper’s road movie Easy Rider came out (Gram and Ian had already appeared in Peter Fonda’s movie The Trip – there’s a humorous inside take on that in Breakfast). Say what you will in retrospect, Easy Rider changed us, or more accurately, showed us to ourselves. It wasn’t a totally pretty picture, which is why I think it’s still pretty good. Easy Rider basically added the soundtrack to an updated Travels with Charley. One came at the beginning of the sixties, the other, toward the end. Breakfast In Nudie Suits, pretty much the middle.

I didn’t hear country music at home in Buffalo, and I believe my love for it began at those roadside stops on the road to Wisconsin in the late ’50s early ’60s, when someone dropped a quarter in one of those fascinating silver machines in every booth and out came “King of the Road” or “Big Bad John.” (There was a towering cutout roadside miner beckoning us to explore an iron mine in the U.P. of Michigan: Can we Dad?; I still pass it every year, and I still call it Big Bad John.) I loved this strange new-to-me music, but didn’t fully realize what exactly it was until I heard Gram Parsons take on it a few years later.

By this time in my life, a New Englander named Ian Dunlop had known Gram Parsons for a few years. They were living together, gigging together, doing all kinds of things together. By the time I was reading Travels with Charley, Ian had already played scores of gigs with Gram and their International Submarine Band, sharing the bill with other bands that “made it” such as the Blues Magoos; Ian paints one great and humorous scene of the Sub Band opening for the Young Rascals before a huge crowd in Central Park. We’ve read in other books the intricate details of those days, as these relatively unknown young band members came together, drifted apart, re-grouped, stole each others’ names, and so forth.

But Ian Dunlop’s tale of that road does not re-examine with a detached journalist’s eye those well-documented times. Rather, through the eyes of a young bass player at the center of that then-tiny solar system – one that not one of them could have imagined would ever become so analyzed – Ian takes us along on a long, meandering, sometimes lonesome journey back East, the opposite direction from America’s standard road tale of lighting out for the Territory and going West young man. He’d done his time in L.A., swirled it around in his mouth, and like thousands before him, found it was not the promised land. No, it was time for him and his band, now the Flying Burrito Brothers, to head back East, or at least that general direction, with a somewhat less Gatsby-esque focus, and see where that road would take him, leaving Gram Parsons to be the Jay Gatsby of country rock on the West Coast.

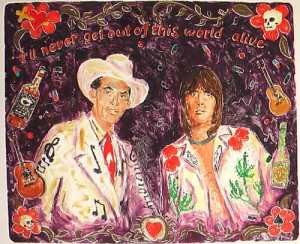

Ian Dunlop, besides being a musician and a writer, is primarily a painter. The original cover he painted for the book is pictured above. Only God and the publisher know why they changed it to this black and white shot of Gram Parsons at left. (Ian will tell you that he finds publishers about on the same plane of existence as record producers.)

Unlike what the current cover implies, this is not a book about Gram Parsons. Well, not just anyway. Gram and memories of Gram hover over the tale and inform it. He is an omniscient presence, and the lonesome road induces Ian’s mind to try to construct a whole of his recent past, all the gigs, the friendships, the heartaches and joys – a past that, at the time, the author would never have imagined would be so central to so many of us. The beginning of something.

To set the scene in the timeline of that “beginning of something” (skip over this paragraph if you’re familiar): Gram had left the International Submarine Band and joined the Byrds. Sub Band members Ian Dunlop and Mickey Gauvin were getting the distinct sense that no one, the public nor the record companies, were ever going to “get” this “country thing.” Largely for lack of gigs and therefore food money, Ian and Mickey decide to leave the Sub Band just as Gram is telling them a guy named Hazelwood is interested in an album (but no advance). Together with Barry Tashian and Billy Briggs of the Remains (one of the great garage bands of the day who opened for the Beatles tour and found the experience lacking), they decide to form their own band.

Outside a taco joint somewhere in L.A., Ian and Mickey decide to call it the Flying Burrito Brothers. Along the way, the very first incarnation of the FBB picked up some other players including Bobby Keys, Leon Russell, Junior Markham, J.J. Cale, Ed Davis, etc., whoever “dug” what they were trying to do, which was old-school rhythm and blues-based rock ‘n roll with a side order of country – definitely not what the rest of the country was listening to at the time. (Gram told an interviewer after he himself “borrowed” the FBB moniker and made history with it: “The idea’ll keep going on. Whether I do it or anybody else does it, it’s got to keep going.”) For more on the history of these bands, well, their are numerous books, articles and websites that cover it all in exquisite detail.

Long after Steinbeck’s death, a few critics began to analyze every sentence, every reported conversation with someone, from his Travels with Charley. And, by God, they found out he was a liar, that is, a writer of fiction. Faulkner once said he didn’t give a damn for the facts, just the truth. Dunlop is not a liar (that is a writer of fiction), but Breakfast in Nudie Suits reads so much like a work of literature that the reader must occasionally pinch him- or herself and realize this is reportage based on actual memory. Ian says that he wrote Breakfast as if it had been written in 1968. On the last page he leaves us wishing for more, but it is fitting for this memoir that it ends when it does. As the author told this reviewer, “The narrator is speaking from the 60s. I left the U.S. in ’68 to another continent and civilization, so my last experiences were preserved, sealed, vacuum packed.“

Ian’s road reminiscences take the same circuitous route that his loaded-down van did (Mickey and Barry T in a different van ultimately take a more direct route cross country). It is not my purpose here to recount any of Ian’s experiences on that road to discover America. Why? Mainly because you must read this tome yourself. (Although, I must say, Barry T plugging into a windmill somewhere in Kansas is one of my favorite LOL images). A word of caution to those who expect non-Faulknerian linear discourse. Ian’s thought patterns mimic his somewhat zig-zag route and the ever-changing landscape; expect random memories to pop up in the middle of Paducah or wherever. I’ve done many cross country trips alone and, believe me, especially after putting a lot of miles behind one for the day, that’s how the mind works. He resists sudden urges to turn back, to try to finish what has already been set in motion in an altered direction just by his leaving.

So why should the “target market,” assumed to be those somewhat interested in music, which is the rack I expect you’ll find this book, read Breakfast In Nudie Suits? If it isn’t yet another biography of Gram, what’s the point?

Let’s face it, Gram’s almost 27 years have been covered. Minute analysis of his life will no doubt continue. But I’m convinced this would be the book that Gram himself would like best. Even the telling scene when Gram is having a bad trip on acid and the band is trying their best to bring him out of a very bad place (I won’t give anything further away), together with, at other times, Gram’s jovial though understated banter with band mates combined with that inexplicable feeling of a higher power directing his every move — these are the elements that Ian provides of his friend Gram Parsons.

Not many of us mere mortals have the guiding hand of a muse from the cosmos. The rest of us are rock ‘n roll soldiers. Ian Dunlop continues to be a rock ‘n roll soldier, and high honor should be bestowed on this brigade, one that includes a host of names that pop up in Ian’s narrative and many that do not.

Ultimately, Ian’s recollections are transcriptions of a seemingly minor branch of the big river that is rock and roll history, much of which has been covered extensively by “professional writers.” But if you’re like this reviewer, you lust after the memories of those who were there at a critical moment of creation – a branch in the stream whose tiny tributaries and eddies remained almost uncharted until recently. While the elements of this story, the story of the birth of country rock (and even the bending of the longest-lasting and best-known rock band in history to embrace it and thus forge a second act that takes them the rest of the way home) have yet to be fully grasped by “the general public,” each new generation, first-hand evidence suggests, hunger for and have a need-to-know thirst for accounts such as this.

This personal chronicle is up there with the best, e.g., Al Kooper’s Backstage Passes and Backstabbing Bastards, Levon Helm’s This Wheel’s On Fire, and Eric Burdon’s Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood among others. Of course all of them achieved some greater degree of success (although Al’s and Eric’s and even Levon’s accounts of getting friendly fire from their brothers in combat do bring their stories back to the rock and roll trenches).

So who “gets” this book?

Gram would get it and love it, that’s for sure. And perhaps Steinbeck, Kerouac, and even Nabokov, or at least Humbert Humbert and Lo, too.

Ian Dunlop, a rock and roll soldier.

Originally published at Gram Parsons InterNational (http://gramparsonsinternational.us)