Acknowledgements:

I sincerely thank Kevin Nutt of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, and the Alabama Folklife Association for putting at my disposal the writings of Doug Seroff and Lynn Abbott, published in: “Tributaries, Journal of the Alabama Folklife Association”, 2002, Joey Brackner editor.

It has to be mentioned, in addition, that the main sources exploited by Seroff and Abbott come from “The Indianapolis Freeman”, a weekly newspaper (1884-1927) which reported on the black entertainment profession. Circulated nationally, it was the first illustrated black newspaper in America.

———————————————————————

Entering the Oakwood Cemetery Annex in Montgomery, Alabama, it is hard to ignore the elaborate sign with the photo of country star Hank Williams, directing to his impressive burial memorial. Only a few hundred yards away, a man named Butler May is buried under a simple, inconspicuous grave stone, sharing the tomb with his mother and one of his sisters. Yet, when Butler May died in 1917 at the age of 23, his death was broadly reported in African-American newspapers. The “Montgomery Times” printed that he was the “best known negro comedian in the south and () the highest price negro showman in the country. “The Chicago Defender”, one of most widely read and influential newspapers in the African American community in the early twentieth century, noted that “there probably was no better known performer to race vaudeville fans than Butler May.” The article compared him to Bert Williams, one of the most popular comedians for all audiences of his time, and by far the best-selling black recording artist before 1920.

Contrary to Hank Williams, Butler May has largely been forgotten despite his original-creative performances and tremendous success in the 1910′s. Credit needs to be given to Seroff and Abbott (2002), two historians, who have scrupulously investigated the contemporary newspaper articles and other archival material to shed light on this brilliant showman who, unluckily, left no copyrighted sheet music or records. The scholars call him the first full-blown, professional blues star, who was already at very early age famous throughout black America. Later scholars called him “an early Ray Charles” (Marshall and Jean Stearns, 1966).

To put his role and impact into full perspective, I believe it is worthwhile to sketch the historical context of his career in the beginning of the twentieth century.

LA BELLE EPOQUE AND THE ARMORY SHOW: “ISMS” RULE ART

From a world history perspective, the most noticeable trend in the history of the late 19th century was the domination – driven by a booming industrialization – of Western Europeans over Non-Europeans, a domination taking many forms ranging from economic penetration to outright annexation (T.A. Brady). The Western economic expansion went parallel with a boiling social life, penetrated with the solid belief that science and technology could solve all problems. The period 1890-1914 was a time which the middle-class, bathing in luxury, had every reason to describe as “la belle époque”, ignoring however the immense poverty of the labor class.

The technological innovation was accompanied by powerful currents of cultural transformation. Existing style forms were challenged all over: painting, photography, ballet, theater, literature,… In Paris, the cultural capital and the prime site of modernity, new artistic movements took shape in the bohemian circles formed by artists as Picasso, Apollinaire, Matisse, to name only a few. New born styles were on their turn the generator of counter reactions, as was for instance the Jugendstil which tried to bring back the forms faded out by impressionism.

With the beginning of the 20th century, there was moreover the promise of new musical experiments and developments (Eileen Southern, 1997). Composers like Schoenberg and Stravinsky binned the traditional concepts of melody, rhythm, texture, form and instrumentation. Folk music was for them a source of inspiration: Hungarian and Spanish gypsies’ music reverberated in highbrow compositions, and the rhythms and the strumming style of flamenco guitars were reflected in classic piano works. Also Ravel, to name another, was seduced by folk songs from around the world, including by the newly popular African-American ragtime. Already at the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris, the African-American cakewalk dancers impressed both the audience and classical composers.

In America, the turn of the century is commonly called the “Progressive Era”. In the decades before 1900, America had been transformed into a modern, industrial society. While in 1860, most Americans still lived on farms or in small villages, at the end of the 1910′s half of the population was concentrated in only a dozen of cities, which were additionally confronted with a strong influx of migrants, especially from Southern and Eastern Europe. The urbanization and industrialization resulted in poor and overcrowded housing, unsanitary conditions, low pay jobs, and appalling working conditions. Waste and corruption in local governments, and power abuse by big, greedy, uncontrolled trusts and companies were also part of the picture. Public health, education, and environment were likewise the victims of the economic explosion in the last decades of the 19th century.

The swift mutation from a rural to an industrial society caused much anxiety among the native white, middle-class which experienced much of the developments as “disturbing” social changes. As a result, a broad movement for social reform arose which left few aspects of American life untouched. The government was, for the first time, transformed into an active, interventionist entity at the national, state and local level. Education was defined as an instrument for social change. Public health officers launched successful campaigns against all kinds of widespread diseases, succeeding also in slashing rates of infant and child mortality. Public parks, libraries, hospitals, and museums were created. To bridge the gap between capital and labor, white progressives called for arbitration and mediation of labor disputes, and many progressive businessmen promoted a new-style “welfare capitalism” that was supposed to provide workers with higher wages and pensions.

However, the “Progressive Era” was at the same time an undemocratic and elitist movement. The existing social hierarchy with a small, white top and a large poor mass at the bottom, was not questioned. Progressive white saw it as their role, as privileged members of society, to deploy a certain degree of responsibility for the less fortunate, without however reversing power relations. The reformative whirlwind swept alongside the African-Americans. Disfranchisement spread, and the segregation of African-Americans was reinforced. A symptom of the failure of addressing the social and juridical position of the black population was the persistence of lynching, and of race riots. The end of the 20th century witnessed more lynchings than legal executions. The Jim Crow laws, relegating African-Americans to the status of second class citizens, were at their heydays. And though some whites saw lynchings as distasteful, the majority considered them to be necessary elements of the criminal justice system because African-Americans were supposedly prone to violent crimes, especially the rapes of white women. Thus, while the Progressive movement brought significant change and progress to white Americans, it was predominantly a movement rooted in and beneficial to white, northern, industrial cities. It was a time of “vicious, state-sponsored racism”, that for African-Americans qualified as the single worst period since Emancipation (D.W. Root, 2006). Racism was the norm, not the exception.

The African-American needs escaping the attention of policy makers in the White House, they needed to tackle their own problems. Reformers as Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois were the most notable fighters for equal rights. W.E.B. DuBois’ “The Souls of Black Folk” heralded a new, more confrontational approach to civil rights. “The problem of the 20th century,” W.E.B. DuBois stated, “is the problem of the color line.” In February 1909, the “National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was founded to start paving a way to create more social equality. By 1914, the NAACP had 6,000 members and offices in 50 cities.

Yet, as a whole, the “Progressive Era” was one of America’s most creative and innovative periods in the broad realm of culture and arts. Like in Europe, new forms were tried out in several sectors. In the hands of Alfred Stieglitz, American photography for instance became an art form for the first time. Modern architecture was given form by the pen of Frank Lloyd Wright. The Association of American Painters and Sculptors organized in February-March 1913 in New York the first international exhibition of modern art in the United States, the Armory Show. The exposition was nothing less than a revolution, and is commonly seen as the start of modern art in America. Next to European plastic art, it showcased the work of American artists like the post-impressionist Prendergast and the cubist sculptor and painter Max Weber. Realism, Primitivism, Symbolism, Fauvism, Dadaism, Futurism, and Cubism were the words in vogue.

As for the music? Progressivism was not immediately on the agenda. Most of the black and white composers continued writing in the conservative, nineteenth-century European idiom. American compositions remained stylistically at a safe distance from the New Music from European composers as Stravinsky, Schoenberg and Debussy (E. Southern, 1997). This did not mean that there was no quest and debate to define a native American style of music. Nevertheless, most of America’s music, dances and fashions were imported from classic European styles.

AMERICAN MUSIC NEEDS TO BE BASED ON NEGRO MELODIES

In fact, it took the words of a European composer to draw unambiguously the American public attention to the cultural wealth embedded in the Negro sounds which reverberated in American farmer communities, in their factories and from their streets. It was Antonin Dvorak, a Czech composer, acting between 1892 and 1895 as the director of the National Conservatory of Music of America, who firmly fueled the debate for a native American music. Dvorak, whose own music was closely linked to the national struggle of oppressed populations in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, belled the cat when in a New York Herald article, published May 21st 1893, he declared: “In the Negro melodies of America I discover all that is needed for a great and noble school of music.” A week later, he confirmed that his newly completed symphony “reflects the Negro melodies, upon which the coming American school must be based.”

The “curious” Dvorak statement caused nothing less than a riot, in America as well as in Europe. While black musicians were ecstatic, seeing the composer’s statement as “a triumph for the sons and daughters of slavery and a victory for Negro race achievements”, the ‘white’ reactions were mixed. In America, “the Negro Melody Idea” left some composers wondering what “Negro Melodies” had to do with Americanism in musical art. Others used the statement as a basis for launching a progressive movement for American music, and saw in it a real challenge to merge black folk music in the American idiom. At the other side of the Atlantic, the debate was no less pronounced. Arthur Rubinstein had his doubts when he pondered: “Ah, so they are going to allow Negros free musical education. That is very interesting. They may develop a new melody. It is refreshing of course, in twenty five years or fifty years we shall perhaps see whether the Negros can develop their musical talent and found a new musical style.” Others were more open to Dvorak’s suggestion, but remained nevertheless skeptical. A conductor at Bayreuth could not see how the new American music could emanate from the Negro race, nor could he admit that persons playing by ear (sic) could be taught music properly, or had even given evidence of talent proper in this respect.

Antonin Dvorak told nothing new. In fact, he only worded what the majority of America implicitly or explicitly had long time realized, but had not always and consistently acknowledged. The Czech composer himself has pointed to this mostly latent feeling when, in the same New York Herald article, he underlined that the American musician himself understands the “Negro tunes and melodies” and that “they move sentiment in him”.

Indeed, does it need to be remembered that black music has, from the very start, impacted American music and show business? Not later than the 1820′s, Thomas Dartmouth Rice (1808-1860) had keenly observed the show potential of black song and dance when he brought the Jump Jim Crow to the theater stage, contributing to the foundations of the minstrelsy as the first American popular entertainment business. Stephen Foster (1826-1864), America’s first great professional songwriter, blended different influences, among which the melodies of the African-American slaves. His fame came also from writing black face minstrel songs, but in his best songs he transcended the burnt-cork caricature and expressed a profound sympathy for African Americans (Ken Emerson, 1998). Furthermore, in 1867, a reviewer of the “Slave Songs” wrote: “We utter no new truth when we affirm that whatever of nationality there is in the music of America she owes to her dusky children.” More than a decade before, “Dwight’s Journal of Music” noted that “The only musical population of this country are the Negroes of the South”, and in 1891, two years before Dvorak formulated his “revolutionary” suggestion, we read in the Preface to the Hampton collection of spirituals that these songs are the only American music (Paul Fritz Laubenstein, 1930).

The ragtime wave which, until the second half of the 1910′s, swept over America was still another confirmation of Dvorak’s statement how inspiring and “infectious” black folk music was, and how ‘negro tunes’ could impact mainstream, popular music (1). Although strictly speaking, rag music, in its various expressions, was infused with European harmonies, it resulted foremost from the use of African syncopation. It originated from a spontaneous juggling with styles and forms by black folk artists who managed to appeal to their public in saloons, and on the streets, very often in the red light districts. It was symptomatic of the turn of the century creativity and of the rich and complex folk music which was fermenting in the African-American rural and urban communities, where a young post-Reconstruction generation sought ways to identify itself, and in this way, to retain its self-respect in the face of racism.

THE VENTRILOQUIST’S DRUNKEN DUMMY BLUES

While ‘ragging’, mixed with European melodies, acquired the status of all American music in the period before World War I, another music style rooted in the black population graduated to the status of popular music and spread, especially from 1910, rapidly into mainstream entertainment via sheet music, recordings, musicals, revues, circuses, minstrelsy and vaudeville. It was based on the idiom of the 12-bar sequence. At first, this folk blues was amorphous and undefined, characteristic for a pure oral musical genre, but once ‘notated’ and formalized by professionals on the stage, there was no stopping of its conquering the popular music.

In 1909, a white New Orleans pianist named Robert Hoffman published a piano rag by the title of “I’m Alabama bound”, carrying as subtitle “The Alabama Blues.” (P. Muir, 2010). The song failed to make it into the commercial mainstream, but three years later the situation had dramatically changed when the African-American musicians Chris Smith and James T. Brymn published “The Blues”. The copyrighted print, basically a ragtime song, makes use of blue notes and contains enough elements to mark it as a milestone in the history of notated blues. It ignited a continuous and growing stream of published blues “so that by 1920 the genre had become a major branch of the popular music industry”, both in the South and in the North (Muir, 2010: 9). Dvorak’s statement was again supported by the facts.

Black and white composers like W.C. Handy, H. Franklin Seals and Hart A. Wand had carefully listened to the black folk music echoing from the plantation communities, saloons, brothels and streets, and had formalized these sounds in sheet music, ready to be sold to the large public. The popularity acquired by compositions like “Baby Seals Blues”, “Dallas Blues”, and “Memphis Blues” caught the attention of an ever increasing group of black and white composers, lyricists, publishers and musicians. Blues became a craze, and crossed over into the white music culture, to such an extent that the epithet “blues” in a song’s title often acted as a pure marketing instrument.

However, before it appeared as sheet music, blues already flourished in black vaudeville, and would continue to do so all along the 1910′s. The earliest known account of blues singing in black vaudeville, and even of any kind, is contained in a black journal article in April 1910, reporting on a show at the Airdome Theater in Jacksonville, Florida. The article comments on a stage show where Henry, the dummy of ventriloquist John W.F. Woods gets drunk, and where he uses “blues” for the dummy Henry in this drunken act. “After that, reports of black vaudeville became increasingly common, and by 1912, less than two years later, blues had become a “rampant” phenomenon.” (Muir, 2010: 10).

It is on this black vaudeville stage (2) that we meet Butler May. It is likely that it was Butler May’s sensational stage performance of the blues which inspired Chris Smith in 1912 to publish “The Blues” with J.T. Brymn. It is furthermore probable that W.C. Handy was familiar with the original work of Butler May. Contrary to musicians as Smith, Brymn and W.C. Handy, Butler May has however never bothered to copyright his work, and, unfortunately, he died a few years before black blues was waxed for the first time. As said, we owe it to the zealous work of Seroff and Abbott (2002), who explored reports in show business sections of black newspapers of that period, that we have a detailed view on the major role played by this highly talented pioneering blues performer and pianist. If black vaudeville was the major venue through which the blues was disseminated and has contributed to institutionalizing the position of the blues in popular culture, even before Mamie Smith’s 1920 recording of Crazy Blues, it is largely to be attributed to the creativity and charisma of Butler May.

Simplified, if W.C. Handy has fashioned and polished the blues and prepared its entrance in mainstream culture, it is the raw diamond of Butler May’s blues in the segregated black vaudeville circuit which has contributed to solidifying the popularity of the blues in the black community, from the rural South to the urban North. He was, in the words of Seroff and Abbott, the “greatest attraction in African-American vaudeville”, the “unlegitimized” Father of the Blues. If he was not recognized by his contemporaries as the first great piano blues man or the first blues king, it was only because there was nobody to compare to. He was a “theatrical genius”, who was “beating, cutting and fornicating (sic) his way across the black vaudeville landscape, while spreading his message of the real blues” (2002: 34). While W.C. Handy represented the “respectful” blues, Butler May personified the unadulterated, pure instinct of the blues (2002: 43).

THE PIANO ON THE TRUCK

Who was Butler May?

On August 18th 1894, Butler May is born to Butler Sr and Laura Robinson. The place: Montgomery, Alabama, which was, as an anecdote, the first city in America to transform, in 1886, its entire public transport system from horsepower (or rather: mule-power) to overhead wire, based on a design by the Belgian inventor Van Depoele. It was by the way on this trolley service that Montgomery’s racial segregating seating system was established in the early 1900′s.

Around 1900, Butler May’s father, registered as a farmer, dies and his mother, “a good Christian woman”, member of the Baptist church, has to earn a living for her and her eight children doing menial jobs as laundress, cook or domestic servant. The records show that the family moved a great deal around in the Oak Park section of Montgomery. Already as a young child, Butler had plenty of music running through his veins. One of the neighbors of the family recollects how his mother and sisters were proud to announce, on summer evenings, that their young Butler would be around to sing his own music, and play the piano, installed on a dray or a topless truck driven around by some man. Just try, for a minute, to call this image to your mind of a young child, seated at the back of a truck, singing and playing the piano, and performing from porch to porch where people are enjoying the warm evenings. What a scene this must have been!

The street experience paid off. Only 14 years old, in April 1909, the young Butler makes his first steps in the professional circuit when William Benbow introduced him at the Belmont Street Theater in Pensacola, Florida, as a member of a large show performing under the name of “Will Benbow’s Chocolate Drops Company”. Since 1908 this group included the 23 years old piano player, Jelly Roll Morton, later a seminal figure in jazz, as well as Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, who would be styled as “Mother of the Blues”. When Alan Lomax interviewed Jelly Roll Morton in 1938, Morton described Butler May as “the greatest comedian [he] ever knew”. He was “a very, very swell fellow”, continued Morton, “over six feet tall, very slender with big liver lips, and light complexioned. His shoes were enormous and he wore trousers impossible to get over his feet without a shoe horn. He always had a big diamond in his front tooth. He was the first guy I ever saw with a diamond in his mouth, and I guess, I got the idea for my diamond from him”. Let’s recall that the showy Morton was also known, besides for his musical talents, for his colorful clothing and the diamond in his front tooth.

It is illustrative of the shining career and talent of Butler May that in 1916 William Benbow would team up again with Butler May, but that then they would tour as “Beans and Benbow’s Big Vaudeville Review”. Butler’s stage name “Beans” was by then at the forefront. When they first met in 1909, William Benbow, at the time one of the pioneers of black vaudeville whose professional experience went back to the minstrelsy in 1899, was the mentor. Barely seven years later, Butler May stood in the main spot light.

FROM CHOCOLATE DROPS TO STRING BEANS

Butler May could not have had a better mentor than Benbow. His take-off was remarkable. In the fall of 1909, he was the talk of the town when he staged with Kid Kelly, a vernacular comedian, in a singing and dancing act at the opening of the Luna Park Theater in Atlanta. From the very first night he grabbed the audience. Here, May picks up the stage name “String Beans”, a name leaving little to the imagination as to his physical presence on the stage. It is under May’s stage management, that the Luna Park Theater has been called the first recognizable beacon of blues activity in Alabama.

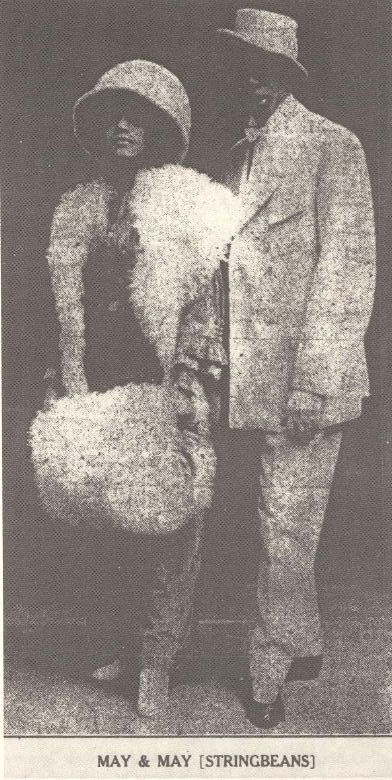

Half a year later, in July 1910, Butler “String Beans” May is assisted at the Luna Park by a “dainty little Southern soubrette”, born in New Orleans, by the name of Sweetie Matthews. She becomes more than his stage partner, and after performances in his very own Montgomery, they are recruited in the fall of 1910 by Will Benbow as a couple, and as headlines to the Alabama Rosebuds Company to tour around in Southern towns. The critics in newspapers heap praise on them, one journalist calling Butler and Sweetie May “the best team ever appearing” in the Hot Springs Majestic Theater (Arkansas). “Only sixteen years old, just two years out of Montgomery, String Beans was the brightest shooting star in the Southern vaudeville universe, which included Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith et.al. (Seroff and Abbott, 2002: 15). Note that the husband-wife team was already then a popular stage format. The comic duo “Butterbeans and Susie” (Mr and Mrs Jodie Edwards), who at one time formed a trio with Butler May, and would remain very popular in the decades following their début in 1920, making recordings even until the early 1960′s (Alan Dundes, 1990), took their inspiration directly from Butler and Sweetie.

Butler’s relation with women was passionately intertwined, to say the least, with the way he managed his professional and private life. Butler and Sweetie split up (privately) already in early 1913. But, in May 1913 they had still been seen working in New Orleans, but mostly separately. In the summer of 1913, Butler May served a few weeks as stage manager at the Iroquois Theater in New Orleans, where he generally performed with Sweetie; “however, this appears to be one of their frequent periods of estrangement” (Abbott and Stewart, 1994). Sweetie would team up that same year on this New Orleans vaudeville stage with another “dainty soubrette”, and no longer with her husband. Yet, two years later they reconciled again and toured together North and East. On Christmas 1915, Sweetie however returns alone to her birth place, New Orleans.

During their two year separation, Butler May staged with different other female partners, like Jessie May Horn with whom he went up North to perform. In the summer of 1914 he shares the stage with Baby Mac, an enthusiastic “pretty, talented, pleasing creature”, and sometime later with Ella Hoke Goodloe, whose sudden divorce from her husband was probably not coincidental to her stage relation with String Beans. Goodloe and May split up already in December of the same year after a “short and sweet” affaire. His first alternative partner, Jessie May Horn was, by the way, never heard of again after April 1914, when she was reported to be in the hospital, “very ill”. The circumstances of the breaking up between Jessie and Butler are unclear. Seroff and Abbott (2002) note that String Beans’ break-ups were generally cloaked in vague references to “crushed hopes” and “severed relationships.” It is not unlikely that the black press muffled stories that would reinforce the negative stereotyping of black performers. “Nevertheless, Beans acquired an odious reputation for abusing female partners” (2002: 21).

CROSSING THE MASON-DIXON

But let me come back to his musical career, which clearly primed. It was in May 1911 that String Beans, then staging with Sweetie, made a historical crossing of the “Mason-Dixon line”, which symbolically divided the Northeastern from the Southern United States. For the first time, they performed in Chicago at the Monogram theater. The Monogram was at the center of the black theatrical district, and had the reputation of being one of the foremost black vaudeville houses in Chicago (owned albeit by a white proprietor). Though the working conditions at the theater were far from opulent – with walls so thin that artists needed to stop singing every time a train passed -, the Monogram would witness many jazz and blues performers of the biggest allure (Mark Berresford, 2010). In any case, sharing the bill in their first week with the “hit-factory in the ragtime”, Chris Smith, Butler and Sweetie May met an overwhelming success with the Northern audiences. Their popularity at the Monogram “opened the floodgates for other Southern acts, and insured a prominent place for the blues in American entertainment” (Seroff and Abbott, 2002: 15). In the press, he is presented as the heaviest team comedian of the lower South, and a journalist mused that “whatever it is that May hands over, nobody knows, or cares, but it thrills and creates riots of laughter” (idem). He gives the audience a “piano burlesque”, continued a reporter, “clever because of its aptness.”

Once he had crossed the Mason-Dixon line and had conquered the Northern audience, his career accelerated stronger than before. From Chicago, Butler and Sweetie moved on to Cincinnati, Ohio and continued south to Louisville, where they “were compelled to take several encores”. The press reported that it was one of the best acts ever seen in Louisville. Especially, the closing song, “Alabama Bound” was very warmly received. Until January 1912, they toured Midwestern Theaters, and traveled further to Jacksonville (Florida), where they stayed at the Globe Theater until spring 1912 to play “crowded houses”. Butler also acted then as stage manager. Still in 1912, he is again on the bill in Chicago and later in Indianapolis.

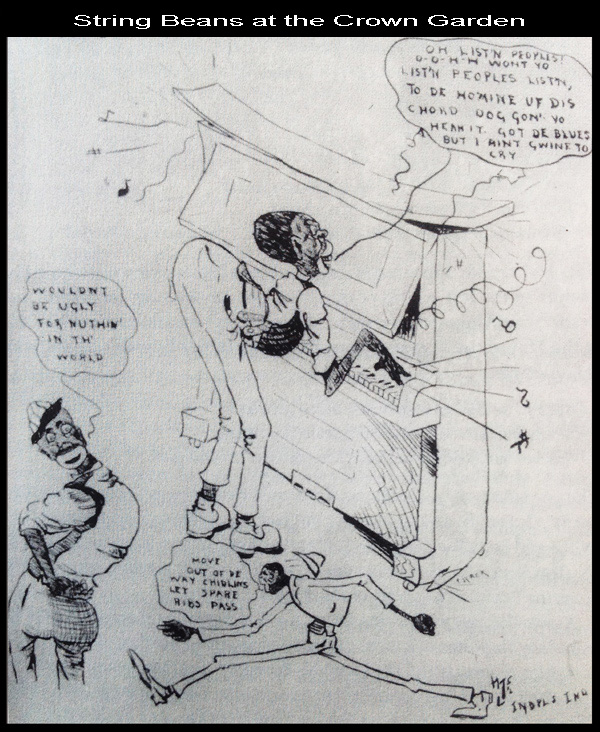

As noted above, in 1913, Butler and Sweetie split up, and we find him working solo in Atlanta in September 1913, and later touring other Southern Theaters, where he brings his version of the “Titanic Blues”, for which he receives several encores every night. In this piano play, he bragged that he was aboard the sinking ship, and survived the catastrophe due to his great athleticism. It is said that in this act he originated the famous blues metaphor of “Elgin movements” (3). As an eyewitness, teacher and folklorist W.L. James has described String Beans’ performance vividly as follows:

“As he attacks the piano, Stringbean’s head starts to nod, his shoulders shake, and his body begins to quiver. Slowly, he sinks to the floor of the stage. Before he submerges, he is executing the Snake Hips…, shouting the blues and, as he hits the deck still playing the piano, performing a horizontal grind which would make today’s rock and roll dancers seem like staid citizens.”

Meanwhile, he discovered another partner in Jessie May Horn with whom he headed North late 1913. He revisits with her the Indianapolis Crown Garden Theater, where he had staged with Sweetie about a year before. Reports describe how the yelling he caused there was almost “deafening”. The theater manager does not hesitate him to equate his talents with those of the great Bert Williams.

From Indianapolis, Butler and his new partner Jessie, who shares in the positive acclaims, continue their success tour further to Cincinnati, Dayton and Columbus amongst other places. The audiences “scream from start to finish”. In March 1914, Butler is again at the Monogram in Chicago, now with his new partner, from where he moves on to St. Louis and Louisville. There, rivaling theater houses are engaged in a legal battle over the possession of the talents of String Beans, who is “drawing unprecedented crowds.”

When he returns, a month later, to Chicago he is alone, Jessie staying in the hospital, as I mentioned above. The tour continues from there to Indianapolis, and in the summer of 1914 he engages his new female partner, Baby Mack, a “pretty, versatile” vaudeville soubrette. They made “a good combination”, reminding the days of Sweetie May. After Chicago and Atlanta, they are, on July 13th 1914, the headline of the opening of the New Champion Theater in Birmingham. Curiously, here in Atlanta, he is faced with a ferocious critic written by a man named Perry Bradford, who puts String Beans in the “class of performers (who) have run down the best houses”, and who labels May as “the smuttiest in business”. Bradford, a friend then of Jelly Roll Morton, is the composer and performer who would, six years later, wear out his shoes to introduce Mamie Smith in the Okeh Records studio to issue the first black blues record. It is likely, however, that Bradford’s critic was inspired more by personal than by professional considerations, String Beans performing then during a few weeks with Bradford’s “attractive” partner Jeanette Taylor. Jealousy was not far away.

In the second half of 1914, May returns once more to the (New) Monogram Theater in Chicago, this time with a new stage partner, Ella Hoke Goodloe, where both are described as “knock-outs”. Before they split up in December the same year, they perform together, amongst other places, in Cincinnati where they are announced as “the best entertainers of their kind in the show business” (Seroff and Abbott, 2002: 29).

A CLEAN ACT AT LAFAYETTE, NEW YORK

Butler May is only 21 years old when he passes another mile-stone in his professional career and his private life. He reconciles with his wife Sweetie May, who had continued to perform, and puts together with her a new act, including new songs, which they perform in Philadelphia. More importantly, however, in early 1915, they invade the legendary Lafayette Theater in Harlem, New York.

The Lafayette, a 1,500-seat theater in the Renaissance-style, was opened in November 1912. At first, the New York theater allowed blacks only in the balcony, but less than a year later African-Americans were also allowed in the orchestra. Having trouble making money, it became in 1913 the first major theater to desegregate. In October 1913, the audience was 90 percent black. The Lafayette would embrace also the talents of Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters, Leadbelly, Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson and many others.

For Butler May, it was yet another major step in his brilliant career, his introduction and impact in New York being as big as it had been in Chicago, four years earlier.

From comments advanced by a theater co-manager, at the same time editor of “The New York Age”, a most influential black newspaper at the time, it can be derived that Butler May’s style had evolved. Had he deliberately cleaned up his act so as not to shock the New York audience? We don’t know, but he certainly had done some polishing work, as it appears from what the New York Age wrote:

“The chief item in this announcement extraordinary is not that “Stringbeans” is appearing at Lafayette Theater, but that “Stringbeans” is associated with a clean act. This piece of information will probably make many a theatregoer out in Chicago and in some cities in the Southland rub their eyes in wonderment, but it is really true – “Stringbeans” is doing a turn at the Fayette which does not need fumigation…” (Seroff and Abbott, 2002: 29)

The article continues to describe Butler’s act with Sweetie as “a riot”, coming from an “original comedian”. However, the article proceeds, he is not conforming to his established reputation as a performer of “coarse, vulgar jokes”, shocking “to the extent that citizens have protested” (idem:30).

Just as Chicago had acted four years earlier as a catalyst in his career, so did his success at Lafayette’s. During the following months, he returns with Sweetie to Chicago, and continues to the East, Cincinnati and Pittsburgh, where they put down 3 week performances. Next on the bill is Washington D.C., where they play a “packed house at the Howard”, which wished “there were more String Beans” as he proves to break all records of box office cards (idem: 31). In Richmond, Virginia, Butler and Sweetie May shared the stage with Ethel Waters. Together with female blues shouters like Alberta Hunter, Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey, Ethel Waters would in the twenties help to cement blues traditions and style in the commercial blues.

After their earlier triumph at Lafayette’s, Butler and Sweetie return to it already in May 1915, where they stage for three weeks in a row, a new record set up for continuous booking at this Northern temple of black vaudeville and entertainment. At that time, to play Lafayette for one week was already the ambition of vaudeville artists… Critics note that he is considered the best drawing card in colored vaudeville, and that he has just the right feeling to give the public what it desires. They add that he possesses “the physical requisites from a comedian; tall, lean, lanky, the personification of a bean pole, with elongated head, liberal mouth, full lips and ample pedal extremities.” (idem: 32).

During the remaining months of 1915, Butler and Sweetie prolong their success at different theaters in the South, and come back once more to Harlem. Sweetie however returns alone to New Orleans for Christmas 1915. This private life event was followed for Butler by a new step in his professional career.

STRING BEANS BECOMES A CULTURAL ICON

Mainly performing solo or with a female partner before, in February 1916 Butler May forms a “four-act” with his mentor, Will Benbow, together with “the little queen of the blues or ragtime shouters” Robbie Lee Peoples, and with Ebbie Burton. Soon the group expanded to eight people carrying the banner name “Beans and Benbow’s Big Vaudeville Review”. Not only the idea of the group is Beans’, also all the songs in the act, which starts at Louisville, are from his hand. Not long after, the group expands to a 15 man strong act when they head for Atlanta, St. Louis, Chicago and Indianapolis. But, whatever the changes in the group composition, Beans reamed the stellar attraction.

Doubtlessly, the “Beans and Benbow Review” was the entrepreneurial high point of Butler May. Artistically, he is also at the top. In 1916, a major critic calls Beans “the blues master piano player of the world.” He had likewise acquired the label “king”. The reporter continued:

“Beans is rapidly developing into a comedian who will go anywhere. It must be admitted that much of his present popularity is due to his oddities, his eccentricities, differing wholly from anything ever seen on a public stage. At this time he has just what pleases colored audiences as we find them at colored playhouses. His strange comedy and blues, especially when at the piano, create a furor.”

The reporter further adds: “I am not much on blues; don’t think much of any variety of them. But if they are anything, Beans has got them. (He) is now the best money-getter. He is known as the salvation man, the pinch hitter for the manager. He puts money in their pockets.”

This statement was hardly exaggerated, for when they staged at the Booker T. Washington Theater in St. Louis in 1916, the police were called to handle the crowds.

Early 1917 the “Beans and Benbow’s Big Vaudeville Review” breaks up, and Beans continues solo. At the Chicago Monogram, he is welcomed with a “wild roar of actual applause from an audience which completely filled the house to see what the greatest stage metamorphose known in history was going to do” (Seroff and Abbott, 2002: 40). Later, in Indianapolis, the critics are equally enthusiastic, printing that the beauty of it all is “that he is good in his originality, saying things that produce a different kind of laughter, the kind that seizes one all over – makes you laugh until it hurts.” The same article retains the same zest when it declares that String Beans is “wholly different to anything the race has produced. (He) can not be pumped dry; he is a fountain. His piano playing is descriptive blues, and strictly a Bean’s creation.” And perhaps the greatest compliment was the critic’s conclusion: “Many try to imitate him in this respect, a sure proof of the quality of his work.”

In April 1917, the Cincinnati vaudeville theater is sold out in advance for the first two performances, and when, two months later, he played in New York it had become clear that String Beans had attained the status of a cultural icon.

Then, remarkably, he accepts to join the large group of “C.W. Park’s Colored Aristrocrats”. Established early 1917, this big, colorful variety group – managed by the man who started Butler’s career, William Benbow – united a mix of blues singing, dancing and novelty acts, including circus entertainment. When C.W. Park advertised for recruiting, he looked for some 60 people, sparing no expenses. It is not unlikely that Butler May fell for the salary offered to him in July 1917 to become a part of this immense show. In any case, he was a valuable asset, being both the “black vaudeville’s brightest blues star”, and, as “The Globe” (a Nashville culturally conservative African American weekly) commented, “the funniest man on earth” (Abbott and Seroff, 2007: 148).

After not more than three months, he left the group, teaming up with the rising blues-comedian duo of Jodie Edwards and Susie Hawthorne. On May 15th that same year, Edwards and Hawthorne had married on stage as part of a publicity stunt, which started – as I mentioned above – a highly successful career of some 30 years in show business known as Butterbeans and Susie (Leo Hamalian and James V. Hatch, 1991). In 1917, as a trio, May, Edwards and Edwards opened a theater in Atlanta and moved on to Jacksonville where they “had a big week”.

A MASONIC DEATH

Can a death be more stupid and bizarre than Butler May’s? On his death certificate, a physician noted briefly as cause of death: “Fracture of … 6th Cervical Vertebra of Neck.” Behind these cold words hide, it is believed, an accident that defies imagination: the available reports point to a rite of passage ceremony that went terribly wrong when String Beans joined an independent Jacksonville Freemasonry lodge. He had turned 23 years old only three months before when, according to a letter posted in The Chicago Defender, during an initiation into this lodge, the small bones in his neck were broken. He was carried to the hospital, but was paralyzed from head to foot. A week later, on November 17th 1917 he died. Two days later, he was brought to his place of birth, Montgomery, where he was buried the next day. His sister, the one who would be laid to rest in his tomb decades later, noted as Butler’s address on the papers: “Traveling Man.”

Not surprisingly, despite his family hiring an attorney in the hope to shed more light onto the circumstances of his death, no more details have been revealed. It is nevertheless probable that the initiation rite derailed when a rope was put around his neck as part of a ceremony that reminds the candidates of their humble and fragile state (4). Moreover, it is reasonable to guess that sometimes such rituals could, certainly in those days, be rough. The fact that he applied for membership of a freemasonry lodge is in itself less astonishing. Indeed, organised African American Freemasonry goes already back to the last quarter of the eighteenth century when Prince Hall, a free, Revolutionary War Veteran received for his Boston lodge the recognition from the Grand Lodge of England. Lodges were, just as churches, an element of the network of fraternal organizations which played an important role in the self-help movement of the blacks. In 1904, African-American Freemasonry counted nationwide some 45.000 members in 1.960 lodges. Well-known names included W.E.B. Dubois, Booker T. Washington, W.C. Handy and also black-face superstar Bert Williams.

Hence, Butler’s move to Freemasonry membership can be interpreted as an expression of the social status he had acquired during the short period between him joining, only fourteen years old, a black vaudeville group, and his proclamation as a “the highest-price negro showman in the country”, eight years later.

In addition to the precise circumstances of his sudden death, other more important questions remain open for discussion. If he was that talented and successful, why did he not cross over to mainstream vaudeville? Writing his own songs, which reportedly contributed to his reputation as the star of black vaudeville, why did he not bother to copyright them? These questions become all the more puzzling when it is known that String Beans was not only musically gifted, but apparently also understood the ins and outs of show business, and testified to having a strong personality who promoted and defended himself extremely well. Illustrative to the latter is the filing, in 1914, of a counter suit charging Louisville theaters that competed for his act, blaming them for being wrongfully detained to appear in court, and thus having to cancel some lucrative shows elsewhere.

Was his black vaudeville loyalty a deliberate choice or not? When offered the opportunity, albeit not frequently, many black artists preferred to leap over to white vaudeville, even if this implied facing blatant racism and experiencing working conditions which were, softly put, discriminating. Why did Butler May remain in the black circuit, when, obviously, he had the talent comparable to an artist like Bert Williams? Did ideological arguments pertaining to the discussion between African Americans who advocated a return to Africa against the integrationists’ view play a role? I do not know. From a reading of the contemporary critics reviews, it is however not hard to discern an artist who came to life on stage, and knew how to appeal and to adapt to his black audience which applauded him loudly. His style was pure, and unpolished to an extent that it was not acceptable to the white audience. He obviously preferred to perform before his very first public, which were the men and women sitting on the front porches of their houses in Montgomery, on warm summer evenings, when he was driving around, playing piano, seated at the back of a truck. It was this public that had made him a star, and that eventually allowed him to earn a more than decent living. Or was he, all things considered, a man for whom the ‘joie de vivre’ primed? This is what we could deduce from one of the requiems, in which a columnist depicts Butler May as “a prince of generosity, never knowing the value of money”, and who was too often the victim of managers taking advantage of him. The columnist, who seemed to have known Butler personally, continues in this sense when he writes that he was “tender of heart”, often speaking of “desiring to be a great star”, “knowing the value of his name”, but not knowing exactly why (Seroff and Abbott, 2002: 46).

HE WAS NOT THE FATHER OF THE BLUES

Was Butler May the real father of the blues? No, he was not. No more than W.C. Handy had the right to proclaim himself the father of the blues, can we grant this soubriquet to Butler May, even if his originality and immense talents, and his prominent role in spreading blues (piano) in the 1910′s can hardly be overstated.

The blues is a music that is derived from the people, and more particularly from the black population which developed it as a means of self-identification and a tool for preserving its dignity. It is out of this folk music that the blues have evolved into a popular musical style, starting at the end of the 19th century, and accelerating during the first decades of the 20th century. It is in the light of this mutation from a folk music to a popular music that we need the gauge the position occupied by individual artist, performers, composers and lyricists. I use the word ‘popular’ in the meaning that tunes and songs have been notated in commercialized sheets, have been brought to the stage by professionals, and have eventually been recorded and spread by radio.

Moreover, to put their role into a proper perspective, I recall the historical context which I sketched above. The decades during which the blues evolved from a folk music to a popular music featured a fundamental transformation of American society. The industrialization and urbanization, reinforced by an immense immigration from the outside, and a massive migration from mainly black people from the South to the North, created the conditions for a market that was open to new forms of entertainment. Even if the mass of immigrants missed a great deal of the new nation’s prosperity, they enthusiastically embraced the recreational opportunities offered by parks, dance halls, ballparks, theaters… It was the context in which a cultural revolution could blossom. All elements were present for a vibrant, urban culture to develop, and it did.

This was also the social time frame where the folk blues could make its way from the riversides and the farm communities in the South to a national phenomenon. The gradual consolidation, on a stylistic level, during the decades preceding World War I, of blues songs towards 3-line verse forms, with 12-measure strophes was accompanied by three major social evolutions of the blues (Jeff Todd Titon, 1990). Firstly, the rural blues spread further on the streets and in the local entertainment establishments of the South, and established its success as a music ideal for dancing and entertainment. Secondly, the blues leaped to the professional African-American stage and acquired its place as part of the shows performed by touring black bands, minstrels, medicine shows, and most importantly, the black vaudeville. Finally, the blues spread from black to white culture through live performances, sheet music and recordings by white singers and bands. A national blues craze was ignited resulting in professionals, even on Broadway, to capitalize on this ‘new’ music.

W.C. Handy and composers like H. Franklin Seals were the names prominently present in the latter development which formalized the blues idiom in a way to commercialize it in mainstream culture. Butler May is the performer and composer who contributed substantially to having black vaudeville pave the way for the blues to obtain a consolidated place on the professional, African-American musical stage. In this perspective, both W.C. Handy and Butler May acted as chief catalysts for creating the conditions which permitted the commercial, recorded blues in the 1920′s to flourish, first as a continuation of the vaudeville-style, and a few years later followed by the marketing of the low-down country blues. Neither of them were the fathers of the blues; all we could say – if we want to stick to the family metaphor – is that they all stood at the cradle of the popular blues, born out of the black folk idiom.

Handy’s fame has forever been linked to the spread of the popular blues. May’s talent and originality, due to his premature death and the absence of copyrighted songs and waxed material, are insufficiently recognized. Yet, he was, in the words of Seroff and Abbott, the greatest attraction in African-American vaudeville, the first recognizable blues star. So, should you ever visit the Oakwood Cemetery in Montgomery, keep in mind that the dimensions of the burial monument and tomb are not always proportional to the historical importance of the deceased.

______________________________________________________

NOTES

(1) The great public entrance of ragtime was made at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, attended by some 27 million people. In January 1900, a Ragtime Championship of the World Competition was held at the Tammany Hall in New York. Rag music was exciting, and outweighed any music that could be offered by classical European idioms. The displacing of the beat from its regular and assumed course of meter made an individual feel a propulsion, a swing, and a musical looseness not known before by the general audience. Though it was a combination of African syncopation and European classical harmonies, the music was by some considered as socially too challenging since it carried connotations to the “low-class” Negro music found in brothels and saloons. Notwithstanding the negative reactions in some circles, by the early 1900s, ragtime had totally invaded the musical and dancing scene. It was all over, finding its way to the whole gamut of forms: sheet music, piano rolls, phonograph records, piano playing contests, music boxes, and vaudeville theaters. The music publishing houses produced piano rags and ragtime songs sheets at a pace hard to keep up with. Popular dance halls were filled with the syncopated sound of the “catchy” and “foot-tapping” tunes and rhythm of the lively music.

Though piano rags became the most popular expression, it is noteworthy that rag time music was in its origin much broader and extended to the vocals and different musical instruments. Ragging was after all a way of playing any song. For the large public, the popularity of rag manifested itself however in the first place in the “coon songs”. Some ‘coon shouters’ would by the way later make the transformation to ‘blues shouters’.

Rag was played by both black and white musicians, and though the name of Scott Joplin is now commonly associated with the genre, most published rag composers throughout the period were in fact white. When it gave way to Jazz around 1917, the genre had meanwhile acquired the status of all-American music.

(2) Vaudeville was a, cheap, theatrical genre of variety entertainment that flourished between the early 1880s until the early 1930s. The performances were made up of a series of separate, unrelated acts grouped together on a common bill. These acts included popular and classical musicians, dancers, comedians, trained animals, magicians, female and male impersonators, acrobats, illustrated songs, jugglers, one-act plays or scenes from plays, athletes, and minstrels. White vaudeville can be linked to the Progressive Era spirit of the white middle-class which wanted entertainment to have an aura of respectability, distinguished from the rowdy, working-class variety halls. Because African-Americans were largely excluded (as audience, and as entertainers) from this white organization owned and managed by a group of white theater magnates, they developed an own circuit through black Vaudeville (see for a seminal work on this: “Ragged but right: Black Traveling Shows, Coon Songs, and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz, Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff, 2007). Even if an organization as T.O.B.A. managed to offer black performers a decent opportunity to act before a black audience, the black vaudeville circuit remained largely discriminated and under-financed, and generated far less success opportunities than the white theaters.

Though vaudeville featured, as said, a wide array of acts as comedians, singers, dancers, jugglers, acrobats, ventriloquists, magicians, even animal trainers, the piano played an indispensable role.

(3) “Elgin Movements” refer to the NATIONAL WATCH COMPANY first incorporated in August 1864, Chicago. Its products were commonly known as ‘Elgins’, and represented about half of the pocket watches in the US. In 1910, it produced its first wrist watch. It was a symbol, at the time, of the nation’s passage from a rural to an urban society, since the watches, once affordable only to the rich, became within the reach of many Americans. So, when String Beans, and later other bluesmen as Robert Johnson and Blind Blake, praised their women for “Elgin movements”, they were talking about the elegance of her body – which, like a watch movement, has curves – as well as how it moved when she walked, or while having sex (see further: (http://www.emusic.com/music-news/spotlight/blueslore-01-elgin-movement/#ixzz1sgZQ878c

(see further: Erwin Bosman, Blues and Black folk music shine on the American Titanic, 2012)

(4) http://www.christian-restoration.com/fmasonry/first degree.htm

___________________________________

READING:

- http://www.doctorjazz.co.uk/draftcards1.html

- http://www.thebluegrassspecial.com

- Doug Seroff and Lynn Abbott, The Life and Death of Pioneer Bluesman Butler “String Beans” May: “Been Here, Made his Quick Duck, and Got Away”, 2002

- Lynn Abbott and Jack Stewart, The Iroquois Theater, in: The Jazz Archivist, vol. IX, 2, December 1994

- Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff, Ragged but Right, 2007

- Alan Dundes, Mother Wit, From the Laughing Barrel, 1990)

- Mark Berresford, That’s got ‘Em!, 2010

- Leo Hamalian and James V. Hatch, The Roots of African American Drama, 1991

- Jeff Todd Titon, Downhown Blues Lyrics, 1990

Comments ()