Can’t Look Away: Musicians, Writers, and More Reflect on 30 Years of Uncle Tupelo’s ‘No Depression’

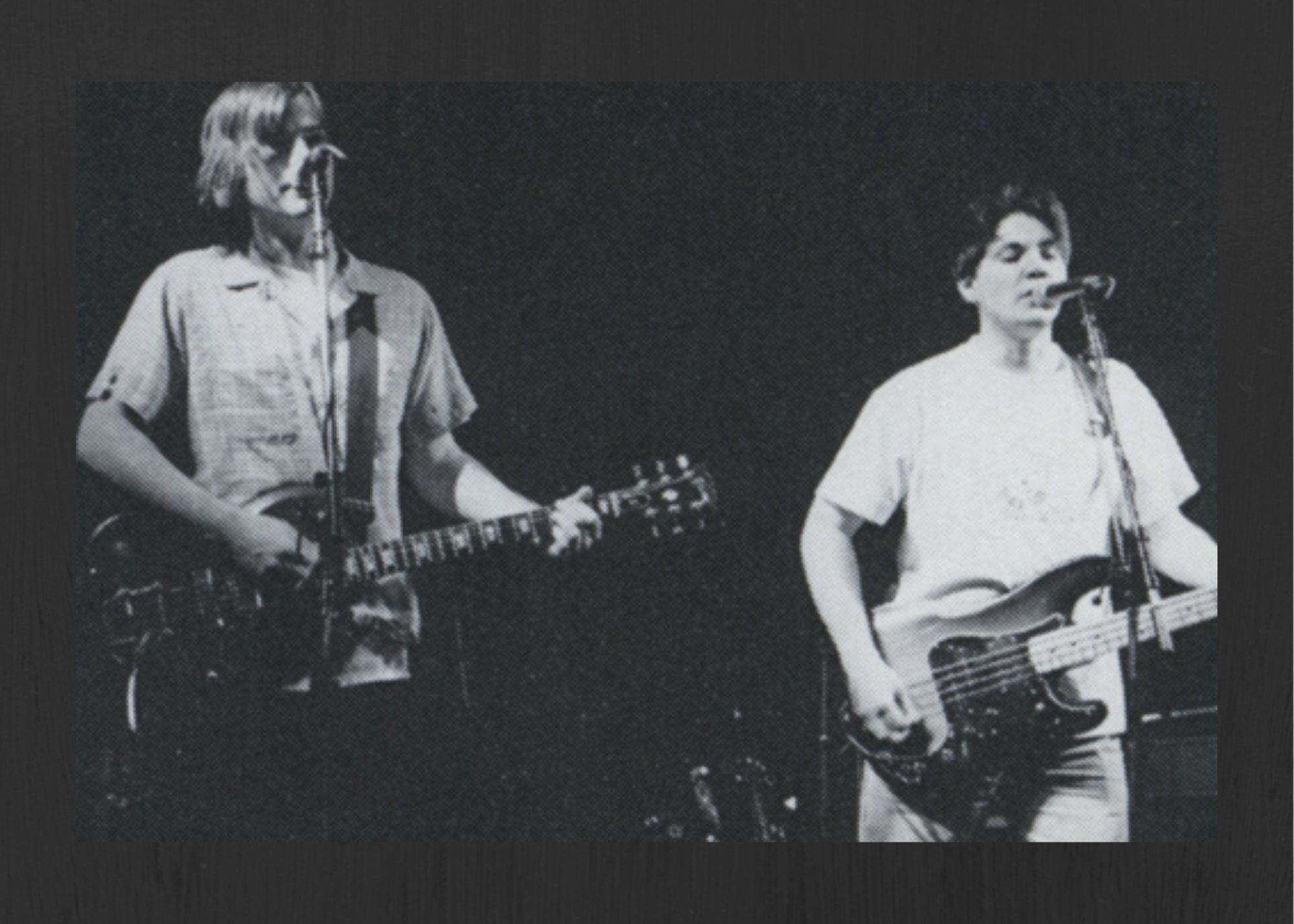

Courtesy of Washington Magazine/Washington University Archives -- https://tinyurl.com/vyutc43

On June 21, 1990, alt-country pioneers Uncle Tupelo (Jay Farrar, Jeff Tweedy, and Mike Heidorn) released their iconic debut album, No Depression. Over the years, the record has been critically hailed as a significant musical mile marker for both its celebration of what came before it (the band was as comfortable tipping its hat to The Carter Family and Lead Belly as it was to The Replacements and The Ramones), as well as for what came after it (in the aftermath of Uncle Tupelo’s breakup, Farrar went on to form Son Volt and Tweedy started Wilco). As part of our celebration of the 30th anniversary of this genre-coalescing touchstone (our interview with Tweedy and Farrar can be found here), we talked to artists, producers, journalists, and other music industry players to get their memories and insights on this iconic roots music touchstone.

Let’s kick off at the beginning. How and when did you first hear of Uncle Tupelo, and what were your earliest impressions of their sound?

Lilly Hiatt (solo artist): I was about 9 or 10 when I stole my brother Rob’s cassette of No Depression. He always knew what was going on, and in his Southern teenage fury, naturally had Uncle Tupelo albums. They had big guitars, lyrical ingenuity, and were talking about real life. Their songs painted such heavy pictures with common words, so that even as a child, before I’d hit any real lows in my life, I grasped their sentiment of despair. They showed it was okay to be a country songwriter and be punk-level pissed.

Valerie June (solo artist): Being a fan of the founders of traditional American music — musicians like The Carter Family and Lead Belly — and later being a fan of Wilco is what led me to Uncle Tupelo. Their sound crosses so many genres. Once I began exploring it, I felt like I’d never really know what was going to happen next. Each track feels like a different portal and they cross through so many different time periods. No Depression is the music of time travel and rule breaking.

Rob Miller (Bloodshot Records): I first started hearing about Uncle Tupelo around 1989 or 1990, when I was working at a college radio station in Ann Arbor, Michigan. At the time, I had been getting a little tired of the punk rock scene and was looking for some new bands that still had the same immediacy and excitement. No Depression is a remarkable beginning and a great snapshot of the band’s journey that can be extrapolated into all these other artists who were kind of on the same trajectory of “I like Black Flag a lot but I’m getting too tired to roll over police cars” or “I may not be a coal miner but I’ve got a shitty job at Walmart and I’d like to get out of this town.” No Depression is the move from “smash the state!” to “I’ve got to put gas in my car to get to work.”

Dom Flemons (solo artist): My introduction into the broader world of Uncle Tupelo actually came through the Mermaid Avenue albums that Wilco did with Billy Bragg. Being a big Woody Guthrie fan, I was immediately drawn in and worked backward through their catalogs, eventually getting to Uncle Tupelo and the No Depression album. The fact that they were able to lean on the traditional covers as well as their own songs was something that was very unique for the time. Sometimes it can be considered a bit avant garde to bring back older traditional songs from artists like The Carter Family or Lead Belly because of the wealth of great songwriters in the current scene. Whether it happened in the 1960s, the 1970s, the present day, or the 1990s with Uncle Tupelo, bands who reinterpret traditional songs become a conduit for their audiences to get exposed to, as my old mentor Mike Seeger would say, “music from the true vine.” When it comes to reinterpreting folk songs, there’s all these different waves and of course Uncle Tupelo has been a big part of one of those big waves of recent decades. Now, both Jeff and Jay are kind of seen as elders of the Americana wave, all while continuing to remain extremely active in the scene.

Brian Fallon (solo artist): I can clearly remember the first time I heard No Depression. I got a call to be a touring guitarist in a band and it was an hour and a half drive to get to rehearsal. At the time, I was getting a bit sick of the punk community because people didn’t like that I was also into Dylan and Springsteen. I was thinking a lot about how I just wanted to hear someone sing folks songs that were somehow mixed with The Replacements and some older country stuff. I already had that first Son Volt album, so I went and bought No Depression for the long drive. It was exactly what I was looking for. I was looking for something that had the energy of punk but also the singer-songwriter vibe that my mom raised me on. No Depression really was all of that in one package. Uncle Tupelo felt like guys who were like me — we don’t fit in anywhere and this music doesn’t really fit in it anywhere — so I loved it immediately.

Rhett Miller (Old 97’s): I got introduced to Uncle Tupelo around 1992 or so when my friend Craig Smith hipped me to them because he thought I’d really like their sound. Craig was always really up on whatever the cool new record was and in those pre-internet days there was no real aggregator other than the Craigs of the world. At the time, there was still that “I like all kinds of music but country” thing going on, even though bands like The Cramps had worked hard to make stuff like rockabilly cool. Honestly, I didn’t exactly connect with Uncle Tupelo at first — some of the guitars have this particular kind of distortion of which I’m personally not a fan — but I thought it was really cool to see a band that had two strong forces at the front of it. I liked the snarky little Ray Davies element in Jeff’s songwriting and Jay was really reverential of some ghosts of country music past while playing this muscular, snarling guitar.

Whitney Matheson (journalist): Honestly, I didn’t hear Uncle Tupelo until about 1995 or 1996, after Son Volt and Wilco released their debuts. In the ’90s, it was just a relief to hear music that wasn’t covered in gloss and glitter. We saw that with the rise of grunge, which — until it started making money — attracted fans who were desperate for something honest after making it through the 1980s. At the time, I was in college at the University of Tennessee, and that alt-country sound had permeated college radio — Southern college radio, anyway — and could certainly be heard in the local music scene. Uncle Tupelo, like so many of the bands that were later influenced by them, felt both new and familiar. They twisted so many genres and influences I loved into a sound all their own and their music complemented that beer-soaked, angst-ridden time of my life.

Ben Nichols (Lucero): I didn’t hear about Uncle Tupelo until after Lucero formed in 1998. We were trying to combine our different musical influences in a similar way and folks naturally told us, “Well you have to listen to Uncle Tupelo.” So basically, I was exposed to the No Depression album at the same time as Anodyne, Son Volt’s Trace, Wilco’s A.M., and the Mermaid Avenue album. Getting all that stuff at once was a lot to process and it was a lot of inspiration. The entire careers of both Farrar and Tweedy up to that point got dumped into my box of influences all at once. One day I would try to write a song like [something from] No Depression and the next day I tried to write like something from Mermaid Avenue. I have a feeling it was similar for a lot of the songwriters coming up around the same time. We all knew about punk rock, we all knew about grunge and alternative, and we all knew about country. No Depression was unique because its sound existed directly in the middle of all of those genres.

Peter Blackstock (No Depression magazine co-founder): I first heard about Uncle Tupelo in the summer of 1990 from Roscoe Shoemaker, a good friend who worked at Waterloo Records and was well-known in Austin for turning people on to new music he was excited about. He told me about the album No Depression and I reviewed it for the Austin American-Statesman shortly after it came out.

Eric Earley (Blitzen Trapper): In the early 1990s, I met my future bandmate Marty Marquis on a mountain in Georgia and he introduced me to the music of Uncle Tupelo. I remember finding an old cassette of No Depression at a record store in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and it struck me that they were mining the same kind of sonically ragged psych-scape that the Seattle bands were pioneering but coming from a kind of blue-collar, Midwestern direction. Farrar and Tweedy showed kids like me who were dabbling with playing in bands that you could infuse punk aesthetics into folk music without losing any honesty or power.

As one of those bands that seemed to achieve its greatest artistic heights more in death than during its all-too-short lifetime (the band broke up just shy of four years after the release of its debut), the stories of Uncle Tupelo’s infamous live shows have mostly lived on through a mixture of newspaper clippings, warbly cassettes, photocopied show flyers, grainy home videos, and a healthy dose of mythologizing.

Did you ever get a chance to see Uncle Tupelo play? If so, what are your memories of their notoriously explosive live show?

Patterson Hood (Drive-By Truckers): I’m a huge, longtime Uncle Tupelo fan and I even had the honor of playing with them once a long time ago. My old band, Adam’s House Cat, opened for them on the No Depression tour at The Antenna Club in Memphis, Tennessee. I remember thinking they were pretty cool, but I wish I would’ve paid more attention to them in that moment. Since we were the opening band, it was during my time of just playing the gig and then getting pretty drunk. I also remember going into the gig with a little bit of good-humored prejudice because I grew up real close to Tupelo and I was like, “Who is this band that is not from Mississippi calling themselves Uncle Tupelo?” At the same time, they truly won me over with their live show because I really enjoyed their sound and their seemingly endless energy.

Greg Kot (journalist): In the early 1990s, Uncle Tupelo played in Chicago a number of times at Lounge Ax, a club that typically booked the best indie bands of the moment. The club was co-owned and booked by Sue Miller, a legendary figure in the Chicago music scene and Jeff Tweedy’s future wife. Even before she and Tweedy became romantically involved, she was advocating for the band and I came out a few times to see them. I was skeptical because their “Hüsker Dü-meets-Woody Guthrie” hype was a bit much. What I heard was earnestness, young guys trying their best to walk in the shoes of their heroes. The early Uncle Tupelo was essentially a punk trio with an old-timey country and folk perspective in their songwriting and subject matter.

Peter Blackstock (No Depression magazine co-founder): In late July of 1990, I was in New York City for a couple of days and happened to notice that Uncle Tupelo was playing at the great Hoboken club Maxwell’s. I took the train over there and saw the band play to a crowd of about 16 people. Despite the small crowd, it was a great set.

Rhett Miller (Old 97’s): I saw Uncle Tupelo play in Dallas at Trees, a venue that was famous for being the club where Kurt Cobain bashed a security guard over the head with his guitar during a Nirvana show. I saw them around the time of their Anodyne album and the room was full of young indie rockers who were not ashamed to say that they wanted more of this. I remember there definitely being camps within the fans. You can’t really argue that either Jay or Jeff is better because they’re very different and they’re both really brilliant. They brought such different things to Uncle Tupelo and it was a pretty magical thing when they were working together. At the time, I thought Jay seemed cool but I was personally in the Tweedy camp because he was like me; he sang high and wrote songs that walked the line between being clever and too clever. I was really into that. Later on, when Wilco’s A.M. came out, I heard “Passenger Side,” and I was like “Okay, this is exactly what I want to do.” My friend Clark went with me to see them and we really enjoyed it. It was such a great, fun show.

Rob Miller (Bloodshot Records): I first heard Uncle Tupelo play live around 1991, after I moved to Chicago. I went to Lounge Ax a couple times a week to hear whoever was playing that night and I caught them on some random Thursday night at one of those shows. As Uncle Tupelo started getting bigger, I had some friends who would drive from Michigan to Chicago every time they played there because they liked them so much. At that time, a band’s live show was still a big part of their development. It wasn’t enough to just make tapes in your friend’s basement and try to sell them somehow. You still had to find some money or a label to put things out and performing live was how you achieved that. It gave a lot of bands like Uncle Tupelo the opportunity to really hone their craft on stage in front of people.

How did you two get connected with Uncle Tupelo, and what do you remember from those No Depression recording sessions?

Sean Slade (producer): When Debbie Southwood-Smith from Rockville gave the Uncle Tupelo demo cassette to us, I remember that Paul and I were immediately impressed. It seemed they had invented a new style of country rock, which I’d always been a fan of. We got more of a glimpse into their daily lifestyle than we usually did with other bands because they ended up crashing at the studio to save money. I remember they were connoisseurs of inexpensive beer: Celebration Lager, $8 a case.

Paul Kolderie (producer): We were so sold on the demos and just wanted to get in and capture their sound as good as we could. Sean and I had been at Fort Apache for a few years and we had just moved our studio to Cambridge, about a mile from where the original studio was in Roxbury. Debbie was the A&R person for Rockville and got Uncle Tupelo signed, but they didn’t have the budget for our big 24-track room. Instead, we did it on a half-inch eight-track machine that we were used to recording with during our early days. Deb was really crucial because she performed the truest A&R functions: she identified a band, successfully got them a record deal, and then had a specific production space and team in mind to partner them with. I think it was a great choice because we knew how to make good, cheap records. We had to work really fast, so luckily their material was brilliant.

Sean Slade (producer): The low budgets we often worked with necessitated working quickly, so our approach was always to try to capture the most exciting “live” performance. Uncle Tupelo had this astonishing raw energy, but they also managed to play as a tight and highly focused unit. That blend came totally naturally to them. Also, Paul and I got to incorporate some country-style embellishments like pedal steel and fiddle into their songs, which wouldn’t have worked at all with the other rock bands we’d produced up to that point.

Paul Kolderie (producer): During the recording sessions, Jay’s black Rickenbacker had some trouble staying in tune, so we brought out some of our gear. Slade had this Gibson SG Junior that was a bit of a secret weapon for us. It had an amazing, driving sound that’s all over the No Depression record. The original “Whiskey Bottle” on their demo had a harmonica on it and I thought it sounded too much like Springsteen. I thought it needed some pedal steel instead. I called up my friend Rich Gilbert to come down and he added this dreamy, moody vibe to it. I think that made a big difference on that song by flipping it from folk rock to country rock. Plus, Jay’s voice sounds so good on that track.

Sean Slade (producer): People always cite the punk rock element of Uncle Tupelo’s sound, but that feel is embodied as much in the lyrics as the music. There’s an unvarnished bitterness and anger to what they’re saying, which made it radically different from the cowpunk music immediately preceding it.

Paul Kolderie (producer): The truest country music influences on the record are in the lyrics. Sean and I thought it was awesome that they were covering The Carter Family. They also had a good idea for the cover to make it look like an old Folkways record. That way it had a classic look to it that really went along with the music inside. The album itself looked a little more serious, like a document of some older tradition. After the record was done, I remember thinking it was really great and possibly the best thing I had done up to that point in my career. I thought it was going to blow things a little wider open than it initially did, but one learns that standing the test of time is really what’s important in a record.

With their unruly hybrid of rock, country, blues, punk, folk, and indie rock influences and the sugar-and-salt blending of Tweedy’s poetically wistful songs and Farrar’s cinematically dour narratives, Uncle Tupelo crafted a stunning sonic statement for their debut record. The album’s 13 tracks wove together buzzy Midwestern malaise (“Graveyard Shift,” “That Year,” “Factory Belt”), acoustic folk sentimentalities (“Whiskey Bottle,” “Life Worth Livin’,” “Screen Door”), individualized anti-war protests (“Train”), furiously-strummed power chords (“Before I Break,” “Outdone”), and boldly traditional takes on The Carter Family’s “No Depression” and Lead Belly’s “John Hardy.”

What are some of your favorite musical moments and lyrical turns from No Depression?

Brian Fallon (solo artist): The first time I heard the album, “Whiskey Bottle” was the initial song that I gravitated towards. Something about it sounded super familiar, like the song had always existed. It was super relatable to me. I don’t like the term “working class,” but the song felt trudging and that was what I was feeling during those years — trudging through mud trying to find my musical calling and inspiration. I remember the feeling of being 19 years old, having no money, and having to decide between buying soup or cigarettes. There was no money for anything, so lines like “The sound of people chasing money and money getting away” described the whole world outside of my own view to me. And the lyric, “Whiskey bottle over Jesus, not forever just for now” — to this day, it conjures up so many emotions. Like c’mon, that’s just good songwriting! That’s one of those canonizing lyrics. I don’t know if he gets enough credit for that one.

Sean Slade (producer): I’ll never tire of listening to “Whiskey Bottle.” That one song and arrangement encapsulates their whole groundbreaking aesthetic, even though we had to politely request that they get rid of the Dylan-esque harmonica parts from the original demo. Thankfully, that edit was fine with them. Oh, and they let me add my whiney singing voice to “Screen Door.” Thanks, guys!

Eric Earley (Blitzen Trapper): I can remember listening to “Whiskey Bottle” riding around in my friend’s Impala outside the sticks of Salem wondering what was making those ghostly slide sounds. I had never seen a steel guitar or played one, but I wanted to capture that kind of haunt and distance. Also, songs like “Life Worth Livin’” and their cover of “No Depression” were formidable acoustic ballads obviously seeking to achieve a timeless folk plateau. Their cover of “Sin City” was where I first heard Gram Parson’s lyrics many years before I was drawn to country and western music outright.

Whitney Matheson (journalist): No Depression is a record you’re going to have an opinion about within the first 30 seconds of hearing it. Those guitars are just incredible and then you’re walloped with Jay Farrar’s voice, which hits a part of the brain that no one else’s quite does. That said, I love Tweedy’s vocals, partly because they couldn’t be more different from Jay’s. “That Year” whisks me back to a very specific place and time. Even when the lyrics seem so simple, they’re straight from the gut. I was listening to “Life Worth Livin’” the other day, which I hadn’t heard in years: “Looks like we’re all looking for a life worth livin’ / That’s why we drink ourselves to sleep.” I mean, holy moly. Those words resonated when I was young, and they still hit me today, although in a different way.

Rhett Miller (Old 97’s): The fact that “That Year” kicks off with a train beat; either wittingly or unwittingly, that went a long way toward drawing a straight line between punk rock and bluegrass. I know other people were doing it, but Uncle Tupelo did it in such a fun way and that’s kind of the same foundation that Old 97’s is built on. In fact, a funny thing happened when we went in to make our first demos. We recorded three songs in a little studio in Austin called Cedar Creek. The day we loaded in, that morning Uncle Tupelo had loaded out from recording Anodyne. The last thing they ever recorded butted right up against the first thing we ever recorded. I felt a bit of a passing of the torch element in that.

Peter Blackstock (No Depression magazine co-founder): The whole start-stop thing they did so effectively on several songs — especially on “Graveyard Shift” and “Factory Belt” — really stood out to me. I remember being on a trip with a musician friend and she remarked on how difficult it was to do that as well as Uncle Tupelo did. I think “Whiskey Bottle” was the album’s best song, mainly because of Jay’s vocal performance. It’s still one of the best he’s ever done. I was drawn more to the songs Jay sang — at that point, I don’t think there was any question that he was the standout talent in the band — but I really liked the easygoing simplicity of Tweedy’s “Screen Door” as well. The song “No Depression” seemed important because of its historical reference, though I would not have said it was one of my favorites on the album. Of course, the historical reference proved very important later; we chose that title for the magazine because we like how it referenced both this contemporary album and the lasting influence of The Carter Family across a century.

Dom Flemons (solo artist): No Depression is a convergence of so many things. In a pre-internet age, it reinvigorated the soul of roots music before the big Americana movement arrived. Uncle Tupelo brought back the soul of Woody Guthrie and Folkways to an audience that may not have been aware of what they were looking for. It was a big deal to have a newer band referencing such an old aesthetic and that album went out into a world that was far more uncertain since you didn’t have the ability to quickly back-reference things like you can nowadays. If you aren’t interested in the popular music of the day, folk music is always ripe to appeal to that sentiment. No Depression came on at a time that people were looking around for something else and it offered something brand new while still being deeply rooted in the music that came before it.

Greg Kot (journalist): Farrar’s songs are built on familiar small-town blues themes. An economic downturn gutted the band’s working-class hometown of Belleville, Illinois, in the 1980s and that Rust Belt darkness seeped into Farrar’s voice and lyrics. The band turned its technical limitations as musicians into raging, idiosyncratic arrangements and juxtaposed them with acoustic country-soul; most notably in the Carter Family cover that would give the album its title. Rockers such as “Graveyard Shift” and “Factory Belt” sound bonkers, in a good way: the herky-jerky push-pull of the drums and guitars defined their sound. Sometimes the self-mythologizing gets a bit thick; but if they sometimes telegraphed just how callow they actually were, their heart and we-don’t-fit-in-but-we-don’t-care conviction made up for it.

Valerie June (solo artist): I’m usually drawn to lyrics, and the themes of drinking and trouble reign as supreme throughout No Depression as they do in so many of my favorite traditional tunes. These lyrics in “Whiskey Bottle” have always stood out to me: “There’s a trouble around, it’s never far away, the same trouble’s been around for a life and a day.” It’s delivering the same age-old message in a personal way, and it’ll never get old. Following those lines are these favorites of mine: “I can’t forget the sound, ’cause it’s here to stay, the sound of people chasing money and money getting away.” Songs that tell the simplest and rawest truth have always gotten me. It forces the listener to look at the ugly in hopes of reshaping or creating an alternative outcome.

Lilly Hiatt (solo artist): Hearing Jay Farrar for the first time, I was blown away by his voice and lyrics. “Graveyard Shift” implores empathy for the working class. “Whiskey Bottle” is like a punch to the gut, but a comforting one that says, “Yeah, we’ve all been there.” Then, to Jay’s thunder, you have Tweedy’s lightning. I see golden strips of light when I hear his voice. I’ll attribute that to its timbre mixed with my synesthesia. In “Train” he sings, “Yes, I have the right to say we all die anyway, but I’d just like to know where does my dying go?” There’s a bleak acceptance there that has comforted me. Well, we all die, so what are we going to do in the meantime? Brilliance.

Ben Nichols (Lucero): I really like the straight-up guitar rock on songs like “Before I Break” and “Graveyard Shift.” It’s pure ’90s grunge, but the guitar is tempered by a different vocal style and melodies. I miss that kind of guitar in a lot of the newer Americana music. Also, the lyrics are more inspired by roots music, and that’s what makes the album unique for its time. It’s a very appealing mix of genres — grunge, rock, country — all in equal parts. What’s great about No Depression is that it sounds like a band from 1990, not a band from 1990 trying to sound like a band from an earlier time.

After Uncle Tupelo’s breakup in mid-1994, Farrar and Tweedy both continued to heavily influence the alt-country/Americana/roots music scene through their follow-up bands, Son Volt and Wilco. By 1995, both new endeavors had their own debut albums, with Wilco’s A.M. out by March and Son Volt’s Trace releasing in September. These days, both Farrar and Tweedy are in the interesting position of remaining vibrantly active in their respective bands (in 2019, Son Volt released Union and Wilco released Ode to Joy), while also functioning as pioneering elder statesmen to a wide spectrum of next-generation artists and bands.

With so many Americana artists claiming Uncle Tupelo (and, by proxy, Son Volt and Wilco) as an influence, who are some bands that you think are carrying forward the wild, unruly spirit of the Uncle Tupelo tradition?

Patterson Hood (Drive-By Truckers): There’s no shortage of great music being made that feels somewhat inspired by Uncle Tupelo. I think maybe Lilly Hiatt and Waxahatchee are two examples of artists who are wholly original and doing their own thing with some of that same Uncle Tupelo spirit applied to it.

Valerie June (solo artist): I think bands like Drive-By Truckers and some of Amanda Shires’ music; especially her Austin City Limits taping. She pushes genre boundaries in a kindred way, while still keeping those Americana elements.

Greg Kot (journalist): The Drive-By Truckers are roughly the same age as Farrar and Tweedy, but their breakthrough came about a half-decade after Uncle Tupelo broke up. They’re one of the best rock bands working today. One of DBT’s former members, Jason Isbell, is practically the poster boy for Americana, and deservedly so. Isbell’s multi-talented wife, Amanda Shires, is as steeped in Bob Wills as she is rock. The Bloodshot Records albums by Lydia Loveless, Sarah Shook and the Disarmers, and Jason Hawk Harris extend and expand the tradition. Also, the tradition rolls in the last decade-plus via Sturgill Simpson, The Avett Brothers, Carolina Chocolate Drops, Songs: Ohia, and early My Morning Jacket.

Eric Earley (Blitzen Trapper): Off the top of my head, I’d have to say Lilly Hiatt, Aaron Lee Tasjan, Nathaniel Rateliff, Lukas Nelson … it’s kind of an endless list, which is a testament to Uncle Tupelo’s influence and power so early on.

Peter Blackstock (No Depression magazine co-founder): It’s kind of hard to say because things have spread out and gotten more fragmented in the ensuing decades. Lots of bands are influenced by Wilco, for example, but it’s largely for things Wilco grew into that don’t really relate to what Uncle Tupelo was very much. I think Drive-By Truckers carried over a little bit of the Uncle Tupelo influence, and thus, by extension, Jason Isbell — though both of those acts also developed their own very distinct style, certainly. At present, American Aquarium might be the band that feels most specifically descended from Uncle Tupelo.

Lilly Hiatt (solo artist): American Aquarium is the first band that comes to mind. Also, Margo Price and Adia Victoria; all folks that tell you what is really going on.

Brian Fallon (solo artist): I feel like Lucero is directly influenced by No Depression. I don’t know if that’s accurate, but I can definitely hear really cool similarities between the two bands. If you listen to That Much Further West and Tennessee, the earlier Lucero records before Nobody’s Darlings, they are way punk and way country. I don’t know if Ben is a fan but it sure sounds like he is.

Ben Nichols (Lucero): I think Lucero and most all the bands we’ve come up with and toured with have been influenced by Uncle Tupelo or at least one of the projects from Farrar and/or Tweedy. They seem to be one of those inspirational forces you can’t avoid, it’s going to get in there.

Rob Miller (Bloodshot Records): I hear parts of Uncle Tupelo in artists like Tyler Childers and Jason Isbell. I can also hear elements of them in one of our newer artists, Jason Hawk Harris, even though he may not even recognize it or be conscious of it. Uncle Tupelo’s genetic code is so deeply ingrained within so many artists. If you go looking for it, you can hear it, but you can’t necessarily put your finger on the specificity of it. That’s where the universality of what they did comes into play.

It’s always tricky business attempting to critically analyze the cultural impact of landmark albums, even more so when a record is saddled — fairly or unfairly — with the burden of spearheading a “new” musical movement. Some fans and critics point to Uncle Tupelo’s No Depression as the embryonic beginnings of a hitherto uncharted scene, while others take a more Seeger-esque “links in the chain” stance to its unique variations on familiar themes. Three decades and counting since its release, the (mostly) friendly debates surrounding the particular significances of Uncle Tupelo’s No Depression show no signs of coalescing into a cleanly condensed one-liner any time soon.

Thirty years on, what do you think is the lasting legacy of the No Depression album and Uncle Tupelo in general?

Valerie June (solo artist): We can thank Uncle Tupelo for helping us clearly see that there are gaps where misfits can slip through the cracks and create planets that could outlive their initial orbits. Uncle Tupelo didn’t ask if it was okay to blend country blues with alt-rock and country music, or if it was okay for them to add raging guitars to it all. They just did it. The lasting legacy of No Depression is in understanding that the “rules” of making music are always asking to be broken. The question is, which artists are going to be bold enough to break them?

Rhett Miller (Old 97’s): The thing about this record that seems most important to me is that in a world where country music was the grossest, most shameful thing you could play, they fully embraced it. They were doing Carter Family songs and Gram Parsons songs and they were setting a template for what would finally become acceptable. They kicked down a giant door by shaking the stigma off of country music; a stigma that had for so long kept many of us from feeling comfortable when getting up on a stage and playing it. It’s like the recorded music equivalent of watching the amoeba take its first steps on land. It was ungainly and awkward, but it was the first time that young people were allowing country music to be cool. For that reason alone, No Depression is a super important record.

Dom Flemons (solo artist): As a student of traditional music, just the idea of people hearing Carter Family songs and Lead Belly songs in the 1990s is such a revelation. The No Depression album helped bring on a new wave of roots music and what we now call Americana. It’s such a wonderful skill to be able to interpret lyrics from outside your own time and connect your own music to them in a way that reaches into the deeper parts of the soul of the lyric. Old blues and folk songs are like Shakespearean poetry in the way that it is material that has been able to stand the test of time because of the advocates that are bringing it to new audiences. It’s just like The Animals doing “House of the Rising Sun” or Jeff Buckley’s Live at Sin-é album where he did all of those beautiful country blues covers. Uncle Tupelo was its own independent orb that was functioning within this broad spectrum of acoustic music and they did such a great job of being a conduit for some of the most beautiful music that has helped to define our culture.

Lilly Hiatt (solo artist): No Depression showed that you could write country songs with blasting electric guitars that speak politically, cheer the working class, and instill a message beyond “beer and women.” In a way, the album harkens back to a traditional folk style and reminds us that everybody can have the blues. There’s also a revolutionary element that gives the green light for bravery. No Depression is a celebration of the misfits that was welcomed by outsiders.

Rob Miller (Bloodshot Records): I doubt that they would cop to “starting something,” but there’s no denying that Uncle Tupelo gets pointed to as a ground zero, when in fact they were jumping into this already vibrant stream and were able to come out with something that added to it; something that has lasted. After Uncle Tupelo broke up, I could’ve filled a dumpster with all the demos we received from bands that were just nakedly aping them. Every tenth email we got was from an address that was like “farrarrules@earthlink.net” or “tweedyisgod@aol.com” — I felt so bad for people like that. That’s the difficult thing. Uncle Tupelo made a lot of what they did seem so simple and made it so universal that other people thought they could do it too. But they couldn’t and still can’t. Not to compare Uncle Tupelo to Dylan, but so many artists are influenced by Dylan and no one sounds exactly like him. Because on its face, that would fail. No Depression and their other records don’t sound dated and they don’t sound exactly like anyone else. Not everyone gets to do that.

Greg Kot (journalist): As Farrar and Tweedy would be the first to tell anyone, they didn’t invent alt-country. It had been floating around for 30 years under different guises. But they did bring it forward and they put their own personal twist on it. If you heard Uncle Tupelo, you heard voices from a small town in western Illinois as filtered through the influence of working-class artists from Merle Haggard to Black Flag. It wasn’t so much about the musical innovation, which was fairly minimal, or the songcraft, as the songs on subsequent Uncle Tupelo albums were generally better. What strikes me about the band now is the notion of three kids from nowhere — and Belleville, Illinois, might as well have been nowhere in the Reagan America of the 1980s — making something out of nothing. There was a naïve earnestness about it that to me is one of the enduring legacies of great rock and roll. Pick up a guitar, write a song, sing your truth, make your own noise, and have the conviction to back it up even when you suspect that no one else will care.

Whitney Matheson (journalist): No Depression is a landmark album that came along at a perfect time when mainstream rock and country weren’t offering much and the most compelling stuff was happening on the fringes. I dug the record, and I really dug all of the music that sprouted from it, whether it was from Tweedy, Farrar, or any of the other bands they influenced. And just on a basic level, I always respect an artist that compels me to dig a little deeper into music history. No Depression certainly does that; heck, they do it with the title alone. Uncle Tupelo wasn’t just a kickass band, they were a gateway.

Brian Fallon (solo artist): I know we have the internet now, but our Jay Farrars, our Jeff Tweedys, our Emmylou Harrises, our Lucinda Williamses — these are our true Smithsonians of musical knowledge. These are the people who cut the way for everybody else to do this. Our group of roots music songwriters, the artists who are helping to write the American story, these people are the Metropolitan Museum of Art for us. I don’t care too much about what Voltaire did in the 1700s, but I do care what Uncle Tupelo did in the 1990s when this wasn’t acceptable music. When I started making records with Gaslight Anthem, I knew that it wouldn’t be true to myself to release records of just loud punk songs. My acoustic songs like “Navesink Banks” were always informed by — and the permission was given by — Uncle Tupelo and No Depression. For people who came up on punk but were also into great songwriting, Uncle Tupelo cleared the path for that to be okay.

Eric Earley (Blitzen Trapper): In 1990, no one else was mixing steel guitars, harmonicas, and heavy cut-time beats with thick, furry guitars. At this point, that kind of production is taken for granted, but at the time no one except maybe R.E.M. and Paul Westerberg seemed to be on that kind of wavelength. Uncle Tupelo brought the twang and a real authentic kind of songwriting, but with mean guitars and punk leanings. They were among the first ragged progenitors of a country-infused, punk-tinged, purely American sound that at its heart was folk music; music of and by the people.

Peter Blackstock (No Depression magazine co-founder): Their legacy is pretty solid, I think, as the most important band of that “scene” or “movement” or “community” or however it might be described. The Jayhawks are the only ones in the same ballpark in terms of legacy. The album No Depression has held up well; I think Anodyne was ultimately their best, but No Depression is still really strong for a debut record. I think the degree of their legacy is readily apparent from one specific observation: If/when Farrar and Tweedy ever reunite for some shows or a tour, it would be one of the biggest music stories of this century.

Paul Kolderie (producer): There were certainly alt-country bands before Uncle Tupelo, but No Depression was such a protean moment for that specific vein of the movement and for that family tree that split into Son Volt and Wilco. Since that record, there’s been more than 30 records that have come out from the people involved, at least. No Depression was the singularity for all that. That alone is quite a notable achievement. Plus, everyone on that record is still working, which is a special part of the legacy as well. This album has really stood the test of time and it’s one of the things I’m proudest of doing.

Patterson Hood (Drive-By Truckers): No Depression is truly a great debut album, but I’m not one of those people that over-romanticizes things. The record was really great, I liked each new Uncle Tupelo album a little bit better, and then Jeff and Jay went on to continue doing great things with Wilco and Son Volt. Decades later, they are both still making great records and those old Uncle Tupelo records still hold up. At the end of the day, from a legacy perspective, what more could you really ask for?