Changing Tradition: A History of Grand Ole Opry General Managers

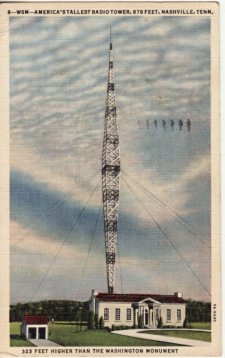

Country music in America has long marketed towards and embodied an eclectic blend of common folk: typically, southern, lower-class, God-fearing, hard-working, blue-collar white men, found in Appalachian homes and hollers scattered well beneath the Mason-Dixon line. From the earliest decades of the twentieth century, families across the United States would crowd around their home radios every Friday and Saturday night and tune into WSM’s Grand Ole Opry on 650AM, eager to hear the familiar sounds of their favorite performers: Uncle Dave Macon to the Delmore Brothers, and Bill Monroe to Roy Acuff, Ernest Tubb and Hank Williams. By the late 1940s, the country music industry, thanks largely in part to the mighty being that is the Grand Ole Opry, had solidified a home in Nashville, Tennessee and showed no signs of leaving. However, as the country music genre experienced a great many changes over the past ninety years, the Grand Ole Opry was forced to adapt and adjust accordingly in order to survive and prosper. One of the main reasons why WSM’s Grand Ole Opry is still the longest-running live radio program in America and one of the most successful performance shows in the history of the music business is fundamentally due to the rigid, subjective leadership decisions of the show’s General Managers for nearly the past century.

“For the past hour we have been listening to music taken largely from Grand Opera, but from now on we will present the Grand Ole Opry” (Escott 2006). George D. Hay, or as he would often call himself on air, “The Solemn Old Judge,” uttered these words at the start of his broadcast radio show, the WSM Barn Dance, on December 10, 1927, forever changing the history of the program. WSM, or “We Shield Millions,” 650AM was the radio station owned by the National Life and Accident Insurance Company, based in Nashville, Tennessee in the early twentieth century, hence the call sign. Hay came to work for the company as the radio director for WSM on November 9, 1925. According to Craig Havighurst’s 2013 book, Air Castle of the South: WSM and the Making of Music City, “Hay found a station in step with national trends in broadcasting. The signal was strong, the talent was decent, and all the programming was live” (Havighurst 2013). Music had played a large part in WSM radio broadcasts, as well as other radio broadcasts around town, but it was not until Hay invited local musician, Uncle Jimmy Thompson, a 78-year old fiddle player from Laguardo, Tennessee, to play some old-time hillbilly music on air that the premise of the show began to take shape. “The Barn Dance program was not formally established on that night, though Uncle Jimmy returned the next week to play again” (Wolfe 1999).

George D. Hay

Weeks went by and Hay continued to feature local hillbilly performers and string bands on the radio program that would come to be known as the Barn Dance and later, the Grand Ole Opry. He discovered through bundles of fan mail that the performers were a huge hit among the rural, working-class folks who tuned their home radios to WSM on Saturday nights and eventually decided to exploit the ‘hillbilly’ appearances and nature of the musicians, whether genuine or not. For example, he changed the names of several of the bands who performed on the program to sound more authentic in a hillbilly sense. Dr. Humphrey Bate, a Tennessee physician, had a band originally named Dr. Humphrey Bate and His Augmented String Orchestra, but Hay insisted the name be changed to Dr. Humphrey Bate and His Possum Hunters (Hurst 1975). In 1935, Radio Stars magazine presented an award to the Grand Ole Opry which falsely praised the program for its “authentic hill-dwellers and dirt farmers with nary a professional among them” (Radio Stars). Hay remained active within WSM and the Grand Ole Opry, though declining health often impeded his abilities to carry out his obligations to the show.

Harry Stone left his radio job with WBAW after being offered a job as the first full-time staff announcer with WSM in February 1928 (Havighurst 2013). With Hay sometimes missing months of work at a time, Stone essentially stepped in as acting director of the program into the 1930s. One of his first major accomplishments in this position came in June of 1930 when he traveled to Washington D.C. to lobby the Federal Radio Commission for a signal boost for WSM to 50,000 Watts, comparable to some of the other larger radio programs in the nation.

The Federal Radio Commission was only allowing the signal boost for twenty stations nationwide, so receiving this boost would ultimately grow the potential reach for the station (Havighurst 2013). Stone also began to revolutionize the talent-hiring process at WSM, gradually moving away from the local musicians and towards more professional-caliber players. According to Charles K. Wolfe, these professional players included The Vagabonds, The Dixieliners, The Delmore Brothers and Pee Wee King (Wolfe 1999). Eventually, as the show’s popularity increased, Stone added a studio audience and split the Saturday show into two separate shows at 8pm and 10pm. The studio audience quickly outgrew the small space inside the National Life and Accident insurance building, however, and a new studio, Studio C, was built on the 5th floor of the building in 1934, which would fit several hundred people at one time. This studio space, according to Havighurst, was much more accommodating to a live music setting, featuring an “arched ceiling to prevent clanging echoes, indirect lighting, acoustic tile walls, a black-and-white checked floor, and a control room behind glass high and to the left on the back wall” (Havighurst 2013). However, as the audiences became too great a burden for the insurance employees to handle, Stone began looking for new homes for the show. Around this time, Stone created the WSM Artist Service Bureau, which served as a booking agency for Opry stars. According to Byron Fay, a nationally-recognized independent Grand Ole Opry historian, the Grand Ole Opry stars were paid five dollars per Saturday night performance in the 1930s. The Artist Service Bureau allowed Opry stars to bill themselves as such during the week as long as they fulfilled their Saturday night Opry obligations. Therefore, by promoting themselves as Opry members on the road, they could make much more money. Of course, the Bureau would receive a percentage-based cut of the paychecks each Opry member received (Fay 2017).

Hank Williams with Harry Stone

Following Studio C, the Opry moved to the Hillsboro Theatre in October of 1934 and lasted until June 1936, when it moved across the Cumberland River to the Dixie Tabernacle in East Nashville, a “rustic venue with a dirt floor, wooden plank benches and roll-up canvas walls” (History of the Opry). Stone then had to meet with the Governor of Tennessee to negotiate the move to the War Memorial Auditorium in July 1939 where he introduced the first ticketed Opry shows. Next, Stone orchestrated the Grand Ole Opry’s move to the Ryman Auditorium on June 5, 1943, where it would stay for the rest of Stone’s tenure as manager.

The fifty-two-week lease, at $100 per week, was more rent than National Life had ever paid. But with 3,500 seats, the venerable hall let more than a thousand additional patrons see the Opry each Saturday night. And still, lines more than a block long began to form outside the theater for every show. WSM improved the house with a radio control room, rudimentary dressing rooms, a public-address system, and new lighting. It hired a crew of off-duty police and firemen for security, plus ticket sellers, stage hands, and electricians…And the Grand Ole Opry had found a comfortable home—a little bit secular, a little bit sacred (Havighurst 2013).

Until his retirement from WSM in July of 1950, Harry Stone had instituted several important, profitable changes to the Grand Ole Opry that transformed the George D. Hay’s small barn dance program with its relatively small reach into a nationally-recognized, 50,000 Watt radio show with a paying live audience of thousands each and every weekend.

As Stone was on his way out, his close competitor, Jim Denny, was quickly on his way to the top. From all accounts I have read, Denny was a bear of a man, and not one to be messed with back in those days. He began his career with the National Life and Accident Insurance company sorting Opry artists’ mail in the mailroom when he was eighteen. He spent three years in the mail room before moving up to the actuarial department and then, essentially becoming the first “bouncer” for the Grand Ole Opry, guarding the back door of the Dixieland Tabernacle on Fatherland Street in East Nashville. In this position, Denny became well-acquainted with most of the Opry acts, allowing him to earn their respect and quickly rise up WSM’s corporate ladder. In 1941, Denny was granted permission to sell homemade souvenirs and concessions at Opry shows, which proved to be an extremely lucrative business for him. These souvenirs included “a hillbilly figure cut out from a quarter-inch plywood with ‘Grand Ole Opry’ rubber stamped on it, wooden ash trays with glass bowls, seat cushions, wooden dogs, songbooks, and fans” (Cunniff 1985).

Later, at the recommendation of Harry Stone, Denny became the first full-time head of the Artist Service Bureau in 1946. According to Frances Williams Preston, former receptionist at WSM, “The Artist Service Bureau under Jim Denny handled the touring schedules of about one hundred Opry artists by 1950…They would get involved with everything to do with the artists…everything they could do to keep that artist’s life, trying to make it a normal life, they would try to do it” (Havighurst 2013). Denny was officially promoted to General Manager of the Opry in January of 1951, following a letter he penned to WSM President Jack DeWitt. In this letter, he stressed, “Without a doubt, we have the hillbilly program of the nation but we are coasting on our laurels instead of trying to improve the program” (Havighurst 2013). At this time, Denny fired perhaps one of the biggest Opry stars in history, Hank Williams, after several occurrences of unprofessional drunken and disorderly conduct. Williams left the Opry to join the Louisiana Hayride but had every intention of returning to the Opry, and even told Denny so. Williams tragically passed away in 1953 before ever becoming a member of the Grand Ole Opry again.

Hank Williams with Jim Denny (far right)

Denny’s entrepreneurial prowess would eventually land him in hot water with DeWitt and WSM. In addition to Denny’s concession and souvenir business, he also co-founded a publishing company, Cedarwood Publishing, with country star Webb Pierce, which was amassing hit song after hit song in the 1950s. Denny and Pierce’s business model was simple: “form a company that signs songs written by top artists, and those artists would provide a natural outlet for hit material” (Cunniff 1985). DeWitt, who never cared for Denny’s flashy suits and brand-new Cadillac cars, was suspicious of Denny’s growing fortune and audited his books in 1953 under the assumption that he was secretly booking Opry acts outside of WSM, but found nothing. However, on August 2, 1955, a WSM Staff Memo was sent to WSM employees that threatened to terminate the outside business of any WSM employee (Cunniff 1985).

In 1956, Denny was named Billboard magazine’s “Country & Western Man of the Year” (Billboard 1956) and not long afterwards, he booked Sun Records star Johnny Cash’ Opry debut, following fellow Sun Records star Elvis Presley’s debut in 1954. In a 1992 interview with Rolling Stone magazine, Johnny Cash recalled having to wait two hours in the hallway before his first meeting with Denny: “He didn’t even say ‘Sit down,’ but I finally sat down across from him. He was busy with his papers but finally, he finally looked at me and said, ‘What makes you think you belong on the Grand Ole Opry?’ (Pond 1992). In 1956, after 27 years of faithful dedication to WSM and the Grand Ole Opry, Jim Denny was fired. WSM President Jack DeWitt offered to double Denny’s salary if he showed full dedication to WSM, but Denny refused to abandon ownership and control of his side businesses. Several Opry stars actually followed Denny after his departure from WSM, including George Jones, Webb Pierce, Jim Reeves, Faron Young, the Louvin Brothers, and many more (Cunniff 1985).

Jim Denny with Jim Reeves

Following both Denny’s and the Opry stars’ departures from WSM in 1956, Jack DeWitt sent a telegram to the current Opry acts:

[W.D. Kilpatrick will] be in responsible charge of all phases of the Grand Ole Opry, will handle the Artist Service Bureau and will be in charge of the Opry on Saturday night. We have felt for some time that it would be advisable to have one person to whom all matters pertaining to the Grand Ole Opry could be referred, and feel that MR. Kilpatrick is well qualified to handle this position. [Kilpatrick] will devote his entire time to the operation…he will not engage in any outside business activities which might be construed as being in conflict with the best interests of WSM or the Grand Ole Opry talent… (Cunniff 1985).

Thus far, Walter David “D” Kilpatrick was the first person hired from outside WSM to manage the Grand Ole Opry. Before he took over in 1956, Kilpatrick had worked for Capitol Records as an Artists & Repertoire director and various roles with Mercury Records. Upon his hiring, Kilpatrick immediately identified a major problem he saw with the Opry: there was no youth. To combat this, Kilpatrick introduced newer, traditional-sounding artists to the Opry such as Wilma Lee and Stoney Cooper, and Porter Waggoner, and other acts such as the Everly Brothers and Rusty and Doug Kershaw (Hurst 1975). “I noticed that we had a lot of Arkansas stars on the Opry, so I wrote every single high school senior class in the state of Arkansas…I offered them a special rate to bring the whole class down to see the Opry. I did that with several states. Before you turned around, I had the Ryman filled with kids” (Hurst 1975). Kilpatrick also had strong opinions on the instrumentation used in country music on the Opry stage. During the mid to late-1950s, country music was in dire need of rejuvenation. With the staggering popularity of rock and roll and rockabilly performers during this time, country music was struggling to stay relevant within the younger audiences, as aforementioned. The dilemma that Kilpatrick, WSM and the Grand Ole Opry faced was reaching newer, younger audiences while not losing touch of the older, traditional audiences the Opry has always entertained.

In an interview conducted with Douglas Green in 1974 as part of the Country Music Foundation Oral History Project, Kilpatrick asserted, “as long as I ran the Opry, they didn’t have drums on the Opry, man. Squaresville, or whatever it may be, that was my conviction” (Interview with D Kilpatrick 1974). In Kilpatrick’s opinion, the drums were a part of rock and roll music, or “the devil’s music,” and “…with all the antagonism that there was between country music and rock and roll, we would lose the traditional audience that we always had” (Hurst 1975). Although Kilpatrick only served as General Manager of the Opry for three years, he was instrumental in the formation of the Country Music Association and named Billboard magazine’s Country and Western Man of the Year in November 1958 (Asbell 1968).

Kilpatrick was succeeded as General Manager of the Grand Ole Opry in 1959 by Ott Devine, who had previously acted in place of WSM Program Director Jack Stapp while Stapp served overseas during World War II. Devine’s important changes to the Grand Ole Opry involved a reversal of Kilpatrick’s previous ban on drums. “I put the drums on—just one drum, that is rhythm drum on…most of them [Opry artists] were very happy about it. Roy [Acuff] didn’t like it too much at first, and he changed his mind. Of course, it wasn’t a big drum set or anything, just a little rhythm drum on a stand” (Interview with Ott Devine 1986). Devine continues, “I got them to put a spotlight on the stage, added spotlights. Didn’t have anything like that. We got new curtains and tried to modernize it every way we could” (Interview with Ott Devine 1986). Through these modifications, Devine was chiefly concerned with the overall improvement of the Opry and Opry shows looking into the future.

Before the 1960s on the Grand Ole Opry, female artists were few and far between, with the exception of comedy acts such as Minnie Pearl or early performers Kitty Wells and Jean Shepard. Additionally, one of Devine’s goals was to include more female talent into the male-dominated show. Two of the first women Devine hired onto to the Opry were Loretta Lynn and Patsy Cline. According to the interview conducted by John Rumble as part of the Country Music Foundation Oral History Project, Devine did not require an audition from neither Cline nor Lynn because he “knew what Patsy could do. And Loretta, she was on a guest appearance a couple of times before we hired her. She’s a real country singer” (Interview with Ott Devine 1986).

In addition to the inclusion of female performers, Devine also booked African-American singer Charlie Pride for a guest appearance on the Opry. Albeit fearful of how the crowd would react, Devine was confident in Pride’s talent as a performer and the audience ultimately agreed.

During the time that Devine served as General Manager of the Opry, the performance requirements were quite relaxed compared to the past. Rather than being expected to perform every single Saturday night at the Opry, performers were now able to make more money on the road outside of Opry shows. Despite the strict requirements for members however, no formal contract was ever enforced under Devine’s leadership. According to the interview with John Rumble, all negotiations were agreed upon through a handshake and a promise (Interview with Ott Devine 1986). After nearly nine years, Devine retired from his position as General Manager of the Grand Ole Opry six weeks after DeWitt’s retirement in 1968.

E.W. “Bud” Wendell took the reins of the Grand Ole Opry on April 6, 1968, two days after the assassination of Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee. As a result, the first Opry show under Wendell’s belt was cancelled due to a curfew placed on the city by Nashville Mayor Beverly Briley, fearful of citywide riots. “Wendell called the mayor personally and said, ‘I’m sure you mean everything except the Grand Ole Opry. We’ve got three or four thousand people coming to town.’ The reply: ‘It includes the Grand Ole Opry. You will not do the show’” (Havighurst 2013). In 1971, WSM started a week-long series of live performances in Nashville called Fan Fair, which is now known as CMA Fest. (Hurst 1975). Wendell was contributory in not only starting the festival, but ensuring bluegrass music had a prominent role in the first Fan Fair. On the first day of Fan Fair in 1971, Wendell hosted an “Early Bird Bluegrass Concert at the Ryman Auditorium” featuring Ralph Stanley and the Clinch Mountain Boys, the Country Gentlemen, Jimmy Martin and the Sunny Mountain Boys, Mac Wiseman, Reno and Smiley, Lester Flatt and the Nashville Grass, and headlining act, Bill Monroe (Hurst 1975). This concert at the Ryman paved the way for other bluegrass-oriented artists to join and perform at the Opry over the years. Current artists as of December 2017 include The Osborne Brothers, inducted as members in 1964, Roy Clark, Allison Krauss, Del McCoury, Jesse McReynolds, Ricky Skaggs, and Dailey and Vincent, the most recent inductees.

As part of Wendell’s governance over the Opry, he further reduced the performance requirements for Opry members from twenty-six performances per year to twenty. According to Ralph Emery, Wendell became known as a friend to everyone involved with the Opry, and even gifted male and female performers with watches and pins, respectively, that said ‘Grand Ole Opry.’ “…He smoothed out everything. They came to love and respect Bud. He was actually the perfect guy to do that” (Havighurst 2013). Wendell left the Opry in 1974, following a successful, six-year career as General Manager to head the newly created Opryland.

Since its move from the War Memorial Auditorium in 1943, the Grand Ole Opry called The Ryman Auditorium home for nearly thirty-one years. However, as the demand to see the live radio show in person increased, and the need for an updated, more comfortable venue for both audiences and performers increased, WSM executives began talk of building a theme-park with a large venue built specifically for the Grand Ole Opry. The concept and construction of Opryland USA ensued. Hal Durham was the last General Manager of the Grand Ole Opry at its historic home in the Ryman Auditorium, and now would be the first manager at the new Grand Ole Opry House.

Bill Monroe with Hal Durham, 1989

In addition to overseeing the move to the new Opry House, Durham was instrumental in the first television broadcasts of the Grand Ole Opry on the Public Broadcasting Service and later, the Tennessee News Network. Durham also allowed a full drum kit on the Opry stage as he inducted many youthful acts into the storied Grand Ole Opry membership roster. Durham held the position as General Manager of the Grand Ole Opry for nineteen years before relinquishing his rule over to Bob Whittaker. A 1995 article in the New York Times entitled “A Still-Stompin’, Still-Fiddlin’ 70-Year-Ole” described Whittaker’s performance requirements for the Grand Ole Opry: “Opry membership is by invitation. Mr. Whittaker, its general manager, says its executives consider a performer’s popularity, desire to join (members are expected to perform at least 12 times a year) and the opinion of current members. ‘If a member isn’t going to contribute to the family, then they’re a liability,’ Mr. Whittaker says” (Jennings 1995). Whittaker’s tenure as General Manager was relatively short-lived and uneventful. He was promoted to President of the Grand Ole Opry Group in 1996 (Hall 1996) before he was succeeded as General Manager of the Opry in 1999.

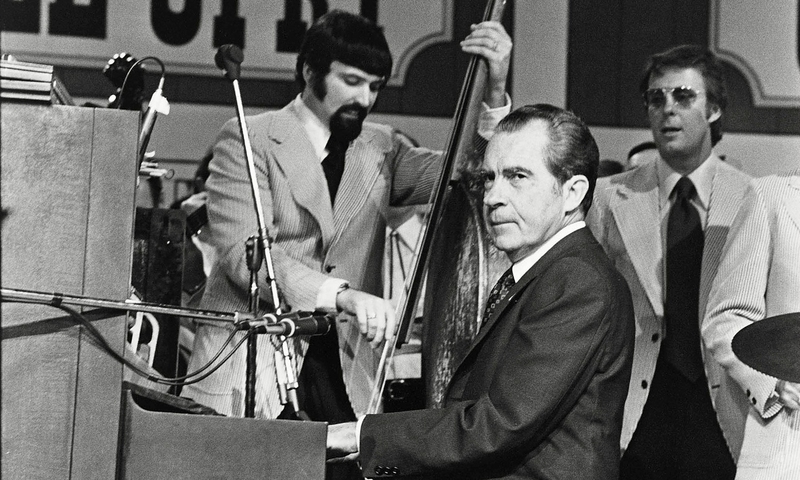

President Richard Nixon at the Opening of the Grand Ole Opry House in 1974

The Peter Fisher era of the Grand Ole Opry was filled with some of the most controversy, yet successful improvements of the show in its history. Shortly after Fisher took over in 1999, he was famously sued by veteran Opry performer, Stonewall Jackson, who felt slighted by Fisher after several of his and his fellow veteran Opry members’ scheduled performances were removed. Jackson penned a letter to Fisher in 2002, ultimately suing him of age discrimination after the removal of these Opry appearances. “(Fisher) said he would work as hard as possible until no gray hair was in the audience or on the stage…He said ‘Stonewall, you are too old and too country to fit in anymore.’” (Cooper 2002). According to Cooper’s article, “’I used to be on the Opry every time the curtain opened,’ said [Charlie] Louvin, who joined in 1955 as half of sibling harmony act The Louvin Brothers. ‘My brother (Ira) and I came here when you had to make 26 Saturday nights a year just to remain a member’” (Cooper 2002). According to Louvin, in 2002 alone, he missed a total of 83 performance opportunities on the Opry because Fisher opted to give those slots to either newer or non-Opry members. Despite this controversy, Fisher’s intentions were hardly anything new, as previous General Managers before him also wished to lower the average age of the Opry fan. Fisher’s tenue was actually fundamental to the development of the Opry in terms of production upgrades. He also relaxed the performance requirements for members, yet again. Now, Opry members were only required to appear ten times per year and spend the rest of the year playing larger shows across the world. Since Opry stars only make Union wage, about one-hundred dollars or so, per Opry performance, this is an attractive benefit of Opry membership.

Next, Fisher oversaw several upgrades to the audio, visual, and lighting aspects of the show, ensuring the best possible experience for the live audience member. Additionally, he recognized the importance and history of the radio program itself, and expanded the reach for the Friday and Saturday night Opry shows exponentially. Fisher recognized the technological advancements of the Millennium and made the Opry available to internet, syndicated, and satellite radio programs. The Opry could now be heard each and every weekend worldwide. In 2010, however, a massive flood plagued the city of Nashville, destroying many homes and businesses. The Grand Ole Opry House was unfortunately not spared. The Opry house was forced to close its door for five months during the constant, painstaking renovation and restoration of the famed concert venue. Totaling twenty million dollars, Fisher was a key part in the swift but successful process. After nearly seventeen years as the General Manager, Fisher stepped down to pursue other interests as the head of the Academy of Country Music in early 2017.

Sally Williams, of no relation to Hiram King, added ‘General Manager of the Grand Ole Opry’ to her already impressive résumé in March of 2017. In 2016, Williams, Vice President and General Manager of the Ryman Auditorium since 2008, was named by Billboard magazine as one of “5 Executives to Watch” on their list of 100 Most Powerful Women Executives in music (Staff, Billboard 2016). She also serves as Chairman of the Country Music Association (2017 Board of Directors). Williams becomes General Manager of the Opry at a time when opportunistic business ventures for her department within Opry are at an all-time high:

“This department” is programming and artist relations, a new division that Williams oversees as Senior VP. It puts her in charge of the Opry’s roster and weekly lineups, but also makes her responsible for concerts and events at the Ryman, the Opry House and three forthcoming venues: New York’s Opry City Stage, opening this summer; Ole Red in Tishomingo, Okla., expected in the fall; and Ole Red in Nashville, due in 2018 (Roland 2017).

I recently conducted a phone interview with Texas country music legend Dale Watson and discussed Ms. Williams’ new role as General Manager of the Opry. Watson, who has performed on the Grand Ole Opry, as well as the Ryman Auditorium several times, assured me of her capacity to effectively fulfil the role:

I know Sally…Sally is probably gonna be the saving grace of the Opry. I mean she’s gonna have to book what the record labels tell her—or finance, you know? But she’s way—she’s been there a long time and she knows all the musicians—she takes musicians’ opinions, you know what I mean?… And she knows the staff that she’s got there—she’s got a great musical staff there and they know what the roots are and I think she’s gonna—I think she’s gonna—we’re probably gonna see more than we’ve ever seen on the Opry now, thanks to her (Watson 2017).

In conclusion, “The Grand Ole Opry was a catalyst which after the war had attracted a pool of talent and an expanding network of promoters, booking agents, publishers, and the like to Nashville” (Malone 2010). Moreover, in the opening of Colin Escott’s book, The Grand Ole Opry: The Making of An American Icon, he asserts, “Country music venerates tradition, and the Grand Ole Opry embodies it” (Escott 2006). From the moment that the Solemn Old Judge uttered the words “Grand Ole Opry” over the airwaves in December of 1927, the foundation of a respected, world-renowned institution was officially born. Despite its small size and reach in the early twentieth century, the Opry gradually grew with the help of its various leaders over the past ninety years. Without the vision of George D. Hay, the sternness of Harry Stone, the muscle of Jim Denny, and the sensible, innovative direction of Kilpatrick, Devine, Wendell, Durham, Whittaker and Fisher, the Grand Ole Opry may have likely ended years ago, like its competitor in Louisiana. However, with the strong support of the National Life and Accident Insurance Company and later, Gaylord Opryland, the Grand Ole Opry thrived and endured through both the historically good and bad times. Country singer Brad Paisley and Opry member since 2001, summed up the essence of the Grand Ole Opry with one quote: “Pilgrims travel to Jerusalem to see the Holy Land, and the foundations of their faith. People go to Washington, D.C. to see the workings of government, and the foundation of our country. And fans flock to Nashville to see the foundation of country music, the Grand Ole Opry” (Roberts 2016).

By: Jimmy Fitch

Works Cited

“2017 Board of Directors.” CMA World – Country Music Association, www.cmaworld.com/board-of-directors/.

Asbell, Bernie. “’D’ Kilpatrick as C&W ‘Man of the Year’.” Billboard, 17 Nov. 1958, p. 18.

Cooper, Peter. “Veteran ‘Opry’ Members Fuming Over Changes.” The Tennessean, 29 Sept. 2002.

Cunniff, Albert. “Muscle Behind the Music: The Life and Times of Jim Denny, I: The Path to

Power; II: Making Friends, Money, Enemies, and a Name for Himself; III: So Much to Do,

So Little Time.” The Journal of Country Music, vol. 11, ser. 1-3, 1985.

“Denny Tops 1955 C&W Poll; Sholes Voted Second Place.” Billboard, 3 Mar. 1956, p. 56.

Escott, Colin. The Grand Ole Opry: The Making of An American Icon. Center Street, 2006.

Fay, Byron. “Artist Service Bureau.” Message to Jimmy Fitch. 10 November 2017. E-mail.

“For Distinguished Service to Radio.” Radio Stars, Aug. 1935, p. 19,

www.americanradiohistory.com/Archive-Radio-Stars/Radio-Stars-1935-08.pdf.

Hall, Alan. “BOB WHITTAKER NAMED PRESIDENT OF GRAND OLE OPRY GROUP.”Business Wire,

14 Oct. 1996, www.thefreelibrary.com/BOB+WHITTAKER+NAMED+PRESIDENT+OF+GRAND+OLE+OPRY+GROUP.-a018764321.

Havighurst, Craig. Air Castle of the South: WSM and the Making of Music City. University of

Illinois Press, 2013.

“History of the Opry.” Grand Ole Opry, www.opry.com/history.

Hurst, Jack. Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry. H. N. Abrams New York, 1975.

Interview with D Kilpatrick [Walter David “D” Kilpatrick] by Douglas B. Green, 1974 June 17 (OH81-LC), in the Country Music Foundation Oral History Project, Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum, Nashville, Tennessee.

Interview with Ott Devine by John W. Rumble, 1986 September 11 (OHC86), in the Country Music Foundation Oral History Project, Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum, Nashville, Tennessee.

Jennings, Dana Andrew. “A Still-Stompin’, Still-Fiddlin’ 70-Year-Ole.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 25 Nov. 1995, www.nytimes.com/1995/11/26/arts/pop-music-a-still-stompin-still-fiddlin-70-year-ole.html?pagewanted=all.

Malone, Bill C., and Jocelyn Neal. Country Music, U.S.A. 3rd ed. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010

Pond, Steve. “The Hard Reign of Country-Music King Johnny Cash. (1992 Yearbook) (Interview).” Rolling Stone, no. 645 46, 1992, p. 118

Roberts, M.B. “10 Quotes About the Grand Ole Opry from Opry Members.” Parade, Parade, 7 Oct. 2016, parade.com/436252/m-b-roberts/10-quotes-about-the-grand-ole-opry-from-opry-members/

Roland, Tom. “New GM Sally Williams Considers The Grand Ole Opry’s Synergistic Future.” Billboard, 16 Mar. 2017, www.billboard.com/articles/business/7727837/new-gm-sally-williams-grand-ole-opry.

Staff, Billboard. “Women In Music 2016: The 100 Most Powerful Executives.” Billboard, 5 Dec. 2016, www.billboard.com/articles/events/women-in-music/7595964/women-in-music-2016-most-powerful-executives.

Watson, Dale. Personal Interview. 15 November 2017.

Wolfe, Charles K. A Good-Natured Riot: The Birth of the Grand Ole Opry. The Country Music Foundation Press and Vanderbilt University Press, 1999.