Collection Showcases the Width and Depth of Pete Seeger’s Legacy

In 1947, Pete Seeger sat in a room with Zilphia Horton and learned to sing a song she was calling “We Will Overcome.” She sang it in a long, slow, freeform, heart-driven alto — what their mutual friend Woody Guthrie called a “full-breasted” voice. She had learned the song a year earlier from some folks who had spent five months striking through a cold, wet Charleston, South Carolina, winter.

Most of them were young black women. They were demanding their tobacco factory be integrated and that they be given a living wage. They didn’t win their demands, though they did receive a small raise. But they came out of those five months with an anthem they’d evolved by singing it every single day before they went home, led by a young black woman named Lucille Simmons. Not much is known about Simmons, but she adapted the old hymn for the purposes of her cause, changing “I” to “we” and improvising a few verses.

Horton taught the song to Seeger and another folksinger named Frank Hamilton. Hamilton taught it to Guy Carawan, who gave it the triplet rhythm and introduced it to civil rights activists in the ’60s. Seeger gave it the “shall.”

All of these details were important to Pete Seeger, who made sure Horton, Hamilton, and Carawan got credit for the song when he filed the copyright. He made sure Simmons got credit whenever he told the story. (He later confessed that he didn’t know Simmons’ name when the copyright was filed.) Like Horton, he believed it was vital to know where a song came from and why people started singing it in the first place before singing it yourself. Knowing these details could help you understand if you meant all the words, or if you needed to add some of your own.

All of these details matter when you press play on the exhaustive new box set from Smithsonian Folkways, because “We Shall Overcome” is where the collection begins.

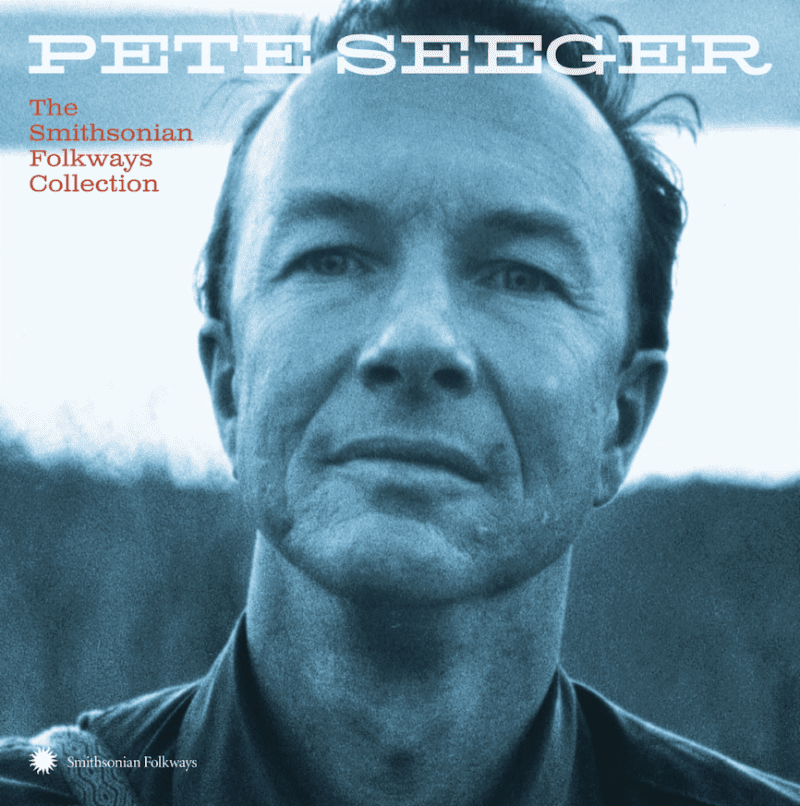

Pete Seeger: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection will release this Friday – what would have been Seeger’s 100th birthday. It is 137 songs across six CDs, accompanied by a 200-page book that offers information on every single track as well as a too-brief but remarkably thorough biography of the artist. (For a good, full biography, grab David King Dunaway’s excellent 1981 book, How Can I Keep from Singing?: The Ballad of Pete Seeger.)

The Folkways collection is the first time anyone has released such a comprehensive collection of Seeger’s material, which is hard to believe, considering his incredible influence on the area of folk music and the fact that his career began around 80 years ago.

Pete Seeger is the third and final entry in a trilogy that began with Woody Guthrie’s centennial and continued with that of Lead Belly. Taken together, these three collections are a stunning testament to the breadth and scope of American folk music over the past century — not only the sheer number of songs that are available for folksingers to draw from, but also the myriad ways that the folk have employed music to carry them through this world. (I’ll let it slide that no women have been given comparable treatment by Folkways.)

Where Guthrie was chiefly a songwriter and entertainer, and Lead Belly was a singer, songster, and multi-instrumentalist, Seeger had a far more academic passion for American folk music. He was, unmistakably, a proficient banjoist and a captivating performer. But unlike his friends and collaborators — these three men all sang together in The Almanac Singers — Seeger was from New England, the son of academics. He studied journalism at Harvard, albeit briefly, and picked up the banjo with the initial intent to join a jazz band. He landed in folk music after stumbling down the wrong figurative side street and found a passion for the form that was both authentic and profound. He developed a commitment to the preservation of folk music that pulled him, like it had fastened a hook behind his belly button, for the rest of his life. We can hear it in every track on the new collection.

Its first disc introduces the uninitiated to Seeger’s career, bouncing across all the songs one could conceivably call his “greatest hits.” It’s worth noting that, aside from the brief success of The Weavers, Seeger barely ever charted with his solo recordings, though his songs — notably “Turn Turn Turn” and “If I Had a Hammer” — enjoyed considerable success through other artists. All of them are here, full of Seeger’s boundless, infectious energy and determined heart. (I found myself clapping along to “Tzena Tzena Tzena” alone in my office because I just couldn’t help it.)

The second disc digs a little deeper into recordings he made for Folkways in the 1940s and ’50s, meaning there is far more from The Almanac Singers and The Weavers. Thus, Disc 2 is heavy on the union songs, with a couple of exceptions — a medley of sea shanties and a turn on a chorale by Beethoven. Tracks include original compositions by The Almanac Singers, who are lesser known than The Weavers but hardly less important in the history of American folk music. We see their names pop up in credits throughout the six discs — Millard Lampell, Lee Hays, Butch Hawes, and Bess Lomax, specifically.

The other four discs tour the kinds of songs at which Seeger was so proficient: environmental songs, peace songs, civil rights songs, labor songs, and songs from the rest of the world beyond the United States. Though Seeger is best known for his delivery of protest songs and the way that he casually boiled down the complexities of war, peace, and social equity to digestible, understandable tidbits, his performance of songs like “Tzena Tzena Tzena,” “Wimoweh,” and “Guantanamera” display his deep love for the world.

Indeed, Seeger’s social activism came from a place of great love and adoration for the capabilities of the human heart and mind, when they work in congress, when their corresponding eyes manage to see past petty things like differences of opinion and priority. At the end of his life, Seeger was known to comment on the political issues of the day by saying it was an exciting time to have optimism. Whenever things like racism crop up, he would remind us, it is an opportunity to see how many more of us are for equality. When pollution happens, it’s a chance to see how many of us are for the Earth. I learned from listening to Seeger that hardship shows us who we are, reminds us how much we have in common, and gives us a chance to see where we can get together and get to work.

I’ve often wondered what Seeger would have to say about the world these past couple of years, but thanks to the folks at Smithsonian Folkways, I don’t have to wonder anymore.

Here are 137 songs to remind us of ourselves. If we listen, we can hear how far we’ve come, what we’ve accomplished, what-all has been figured out and doesn’t need to be worried about again, if we can learn from it. We can hear the way optimism has carried previous generations forward, through impossible times and against impossible odds. Hear how folks have surmounted their differences of opinion in the pursuit of something characteristically American and indeed entirely human. The folk songs are there to help us remember how to persist until — someday, as generations of people have promised one another in song — we overcome. It’s hard to imagine Seeger would have wished for anything better as a birthday gift.

For more coverage of Pete Seeger’s 100th year, be sure to subscribe to No Depression in print. Our upcoming summer issue will feature several stories about Seeger and his far-reaching legacy.