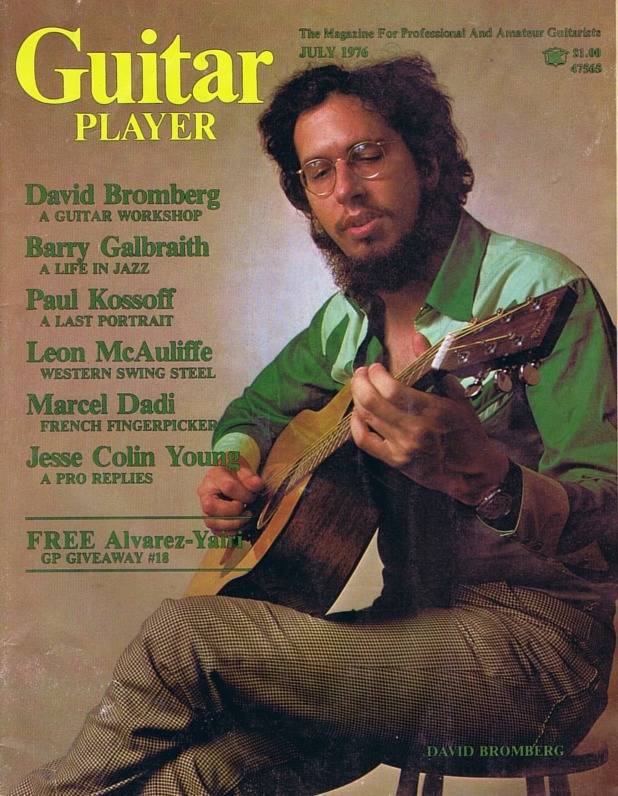

David Bromberg had had enough. The only problem was he didn’t know it. Being on the road for two years without going home for two weeks straight was taking its toll. Bromberg can now look back and realize he was "too dumb" to know he was burned out.

“Where was the musician?” Bromberg remembers asking himself, finding that he wasn’t writing, jamming or practicing when he came off the road. “I had to find another way to lead my life. So I did it. I barely touched a guitar in 22 years.”

Bromberg was recently telling this to Buddy Miller and Jim Lauderdale on a visit to the Buddy & Jim Show on SiriusXM Outlaw Country. Bromberg now says he’s having a ball being back and touring behind Only Slightly Mad. He also owns and runs a violin shop in Wilmington, Delaware, with his wife, Nancy Josephson.

If Bromberg admits to forgetting some of his life’s details, he’s rich on oral history recounting the great moments in his storied life. Like how he ran into the Reverend Gary Davis in New York’s Greenwich Village and convinced him to provide guitar lessons. Or how as an inexperienced young kid, he convinced producer Tom Dowd to let him play guitar on Jerry Jeff Walker’s “Mr. Bojangles.” Or how he was at Woodstock with Rosalie Sorrels. When she didn’t go on, he sat in a teepee during a rainstorm playing guitar and having a ball with Jerry Garcia.

“I think you’re the prime example of an artist who is so diverse and has so many styles,” Lauderdale said calling Midnight On The Water a "transformative record and piece of art.”

“But having all different kinds of music is commercial suicide,” Bromberg counters. “Back in the days of LP’s they didn’t know which bin to put me in.”

Bromberg’s move to Wilmington was the gateway to getting back into music. He had an interest in the making of violins and built a business to identify the instruments people bring to him. It was over the course of lunch with the city’s mayor that Bromberg learned there was once music played up and down the street. The mayor said he was interested in seeing it come back. Bromberg thought the only way he could help if he started some jam sessions for a couple of months--and let them live or die on their own. When really good musicians came from far distances, Bromberg got involved and realized he enjoyed playing again.

Back in the days when Bromberg played for money in coffeehouses, he would buy all the B.B. King records he could afford for a buck at Crown Records in the Times Square subway station. He paid the Reverend Gary Davis $5 for guitar lessons but he got more than he bargained for. It turned into an all-day affair with the Reverend’s wife providing a home-cooked lunch. Bromberg found another way to pay by leading the blind Reverend to church and concerts and where needed. Along the way Bromberg found he loved the black church and never felt as appreciated or at home anywhere else. His curiosity led him to try other black churches to hear the music.

“I became enraptured with gospel music,” he recounts. Bromberg would go to Sam Goody’s and head straight to the gospel section. “I didn’t know what was what,” he admitted. “I’d just buy ‘em by the covers.”

Gospel music was rolling around in his head when he penned a straight-out gospel song called “I’ll Rise Again.”

“In the middle of it, I gave a sermon,” he recalls of the song. “When I heard it played back, I wasn’t sure it should be put out because it was very personal thoughts. I wasn’t sure that I could handle having that out and then I realized these are the things you have to get out.”

Bromberg looks back and surmises that his guitar influences came a little less directly from the Reverend, and more with the fascination of listening to other preachers. Listening to B.B. King, he believes that his idea of tone was emulating Lonnie Johnson and the soul he got on acoustic guitar. The notes were his own, Bromberg says, but the phrasing is a preacher’s.

“If you listen to any of the preachers, you will hear a preacher’s phrasing in every one of them. The difference for those who haven’t been in churches is the use of rests. I tell people the best notes I play are rests. They think I’m making a joke but I’m not. The rest is a very important musical note and it does a magical thing. In a speech or music when you pause, everyone is waiting for the next note or word. I try and preach when I play blues on the guitar.”

Bromberg talked about how he once made a special recording for Flat Picking Magazine. He remembers giving them a country song where he”preached” the solo. “I’m sure all the people who subscribed were terrifically disappointed,” he said deadpan.

Bromberg met Jerry Jeff Walker at the Philadelphia Folk Festival and the two performed as a duo for many years. One of his earliest studio sessions was in Memphis with Walker and producer Tom Dowd. Dowd and Walker were trying to come up with the right arrangement for a song called “Mr. Bojangles.” Bromberg admits he was emotionally overwrought and in tears not being able to play on it.

Finally Dowd was so frustrated with the session's progress he said, “Well let the kid play a little on it.” Bromberg was handed a 12-string guitar and sped up the tempo which satisfied Dowd. Looking back Bromberg says it what was what needed to get it out of waltz time.

Bromberg soon became a "studio guy"and got called into sessions. Bromberg says the stuff he recorded in Nashville is the least known including Aero-Plain, his collaboration with John Hartford. Bromberg had no prior production experience prior to working with Hartford but had the “New York sensibility” Hartford was looking for. “The whole newgrass thing really does come from New York City,” Bromberg related. “It’s New York City pot smoking music.”

Hartford insisted that he nor the other musicians were to hear until it was mixed in sequence. “It was like doing it in a vacuum,” Bromberg recalls of the experience. To make matters worse, when Warner Brothers heard the music, they didn’t know what to do with it. Bromberg knew they were expecting “Gentle On My Mind,” the song that won Hartford a Grammy, and ended up not promoting the album at all.

Bromberg lobbied for the record company to put out “Tear Down The Grand Ole Opry” as a single. The song lamented the dire fate of the Ryman Auditorium and home of the Grand Ole Opry. Three years later, the Ryman was closed and the storied radio show moved to a new Grand Ole Opry House. Hartford wasn’t keen on the song “Hey Baby Do You Want To Boogie” but it got more radio airplay than any other song.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(96)/discogs-images/R-1899340-1337383790-6089.jpeg.jpg)

The album featured Vassar Clements on fiddle, Norman Blake on guitar and mandolin and Randy Skaggs on bass. Years later when the subject of a reissue came up, Bromberg told Hartford “I don’t think we’re done. A lot of them are filler. I think we could make them all really good." Hartford's response was to hang up on Bromberg. Forty-five minutes later he called back and conceded that he had, in fact, asked Bromberg to produce it.

Bromberg has long-since lost the original demo he produced for a young singer by the name of Carly Simon. “I don’t have a copy anymore,” Bromberg related, saying he wouldn’t claim it got her the job but he’d nevertheless love to hear it.

Bromberg appeared on Simon's self-titled debut and his studio credits number in the hundreds of sessions, including two of the Beatles, George Harrison and Ringo Starr, Bob Dylan, Rick Derringer, the Eagles and Willie Nelson. Of Harrison, he recalls going to a friend’s house for Thanksgiving one year. One of the guests was George Harrison. Bromberg and Harrison were both guitar junkies and passed one back and forth between them. “Without trying, we wrote a song, he says of “The Hold-Up” which appears on his self-titled debut album on which both Harrison and Dylan appear.

Years later when Bromberg was playing a show at the Bottom Line club in New York, Dylan came down with Neil Young who had just finished a concert. Dylan asked Bromberg to produce him. The sessions resulted in songs mostly done in the first and second takes. “The song might be the first time you heard it which is the way I like to work," Bromberg stated. He laughs saying that the songs were never bootlegged because he took the tapes home with him every night. Bomberg fondly remembers trading verses with Dylan at a club in Chicago on “It Takes a Lot To Laugh, It Takes a Train To Cry.”

Of his many memories, Bromberg still remembers how Mac Rebbenack (aka Dr. John) cancelled a session in New York to fly out and record with Bromberg in Los Angeles for Midnight On The Water. Bromberg sat in with Willie Nelson on Shotgun Willie and quoted him as saying: “There’s only two songs: 'The Star Spangled Banner' and the blues.”

If Bromberg admits to having hazy memories, you’d never know it. “I got out of the music business for twenty-two years so I forget a lot of stuff,” he says and then goes on to the next story. Miller asked if he knew the Reverend Dan Smith, the harmonica player who was blinded in an auto factory but played with Davis on some long lost tapes. That led to a memory of how Blind Boy Fuller, Gary Davis and Sonny Terry were once on the same bill in Releigh Durham. Bromberg related how Terry hated Davis. “Sonny had a razor and the Reverend always had a gun and here were these three blind men chasing each other around the dressing room.”

When people tell him he should write a book, Bromberg pauses and then says, “Sure, if you hand me the time.” Between recording again, touring and examining violins, life is busy. Bromberg is currently in the midst of a Pledge Music campaign for his forthcoming album “The Blues, the whole Blues, and nothing but the Blues”. The record explores the fondation of the blues and is being recorded with his band and Justin Guip and Larry Campbell who produced Only Slightly Mad. Bromberg credits Campbell with choosing the title of his last album which he says is a line that comes from an old English drinking song.

"I think I was channeling an old English drunk," he says laughing with Miller and Lauderdale.

And just for the record, Bromberg doesn’t use set lists.

“I’ve never had a set list,” he revealed. “We decide the first song and just go along.”

![SPOTLIGHT: William Prince on Origins [ESSAY]](/content/images/size/w720/2025/10/Spotlight-Template-1.png)

Comments ()