Delbert McClinton sets the record straight in the succinct, to-the-point manner that has always been a hallmark of the American music great’s lyrics.

“I’m retired, but I’m not retired from music,” the 81-year-old Texas native says from his Nashville home. “I’m retired from the bus and the hotels and being on the road.”

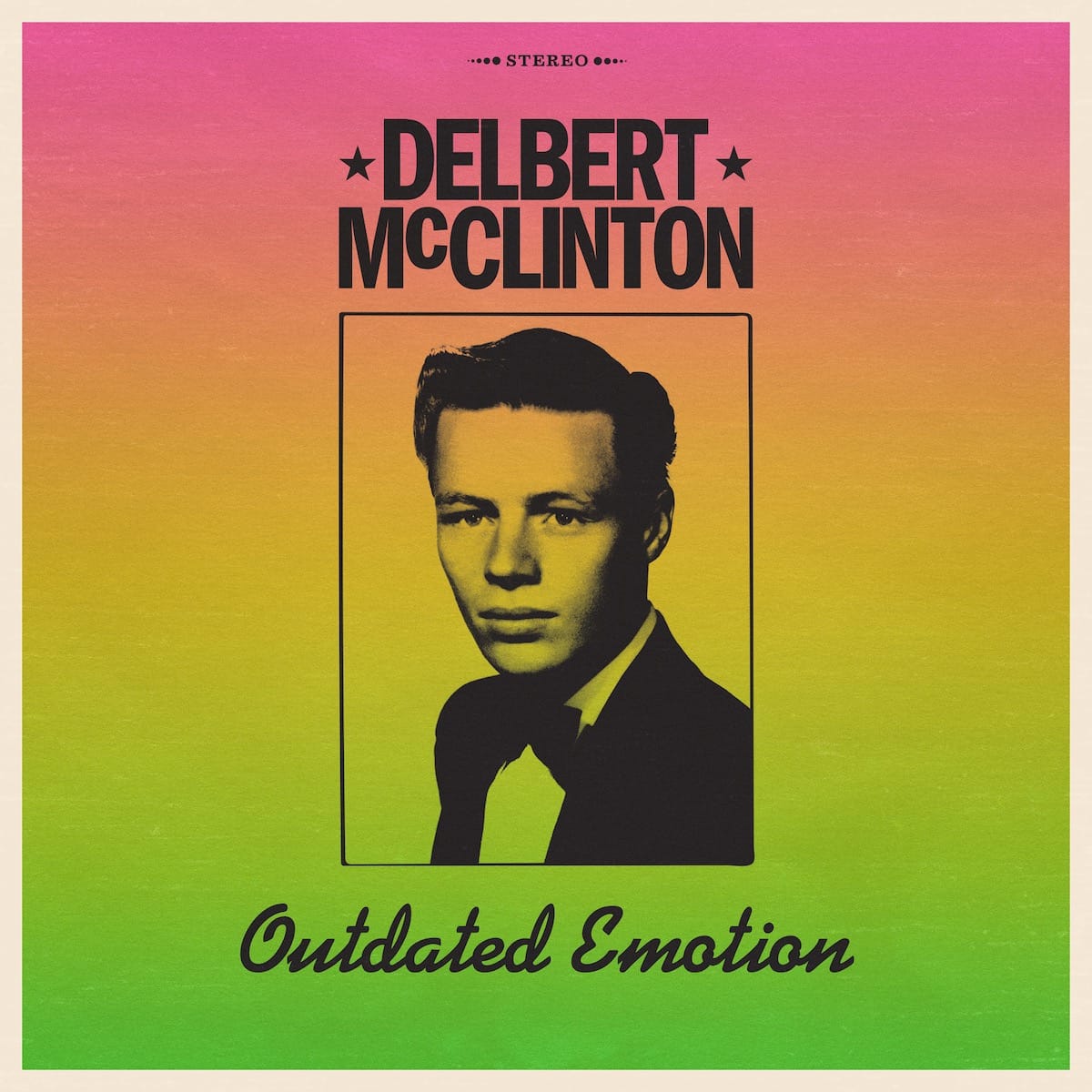

Proving his point, the onetime road warrior released a new album, Outdated Emotion, last Friday. It contains five originals, with the 14 other tracks paying tribute to just some of the songs and artists that shaped him, from Hank Williams, Jimmy Reed, Ray Charles, Little Richard, and more.

They’re the wellspring that inspired him to forge a musical style that has never been easy to categorize — “Americana” before the term existed — melding elements of blues, rock and roll, soul, and country. With a stubborn belief in himself, he has never wavered from that vision, through various ups and downs and at some personal cost: “Screwed up some lives,” he admits. “Screwed up mine some, too.”

As he puts it in the liner notes for Outdated Emotion: “I just always knew that this was going to be what I was going to do, and I was going to do it well. … When I started out doing it, I realized nobody was doing it the way I was doing it.”

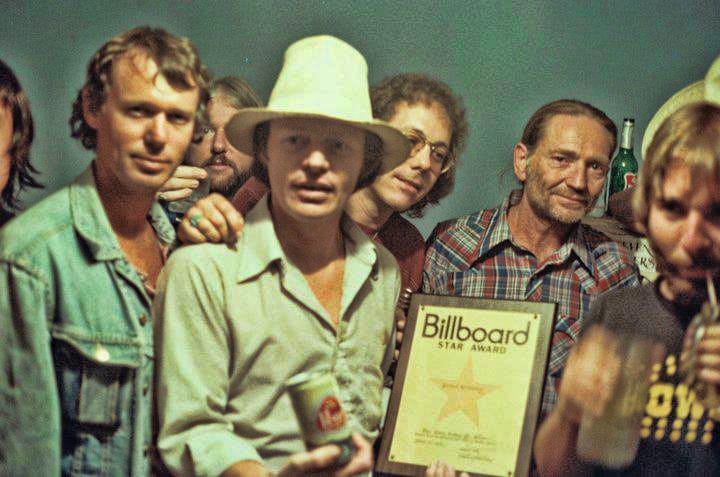

Though he never became a huge star (he refers to himself at one point as “half-assed famous”), McClinton has certainly reached the sweet spot where he has gained recognition as an original (journalists have dubbed him “the Godfather of Americana”) and an intensely loyal following.

He has also totally vindicated his belief in himself, and in recent years he has been doing some of his best work: In 2020, he won the Grammy for best traditional blues album for Tall, Dark, and Handsome (ND review). So he is exiting the road at the top of his game, but he insists it wasn’t a difficult decision.

“I guess some of it has to do with my age,” explains the singer, who had heart surgery seven years ago. “I’m not a young guy anymore. I feel great. I got stuff that doesn’t work very well, but that comes with the lunch.” COVID also played a role in the decision. The lockdown gave him an idea of what it was like to not tour, even though, pre-pandemic, he had already reduced his schedule to just two weekends a month.

What sealed the deal, he says, was when Molly Reed, who helps run his business, asked him what he wanted to do with his tour bus. “And it brought me face-to-face with the truth. And I said, ‘Sell it.’ And she said, ‘You’re retired.’ And you know what, it felt good.”

At this point, the only way you’ll be able to see McClinton perform live again is at sea next January, when his annual Sandy Beaches music cruise resumes after a COVID hiatus. In the meantime, he’s really enjoying not having any commitments. No thinking about travel schedules or dealing with the “petting zoo” aspect of life on the road. You could say he’s stopping to smell the roses.

“I walk around my house here, which is a beautiful place, and I welcome all the spring flowers,” he says. “I find myself being overwhelmed by the beautiful things that [before] I’d generally say, ‘Hey, that’s nice,’ and go on by.”

Hailing His Heroes

Outdated Emotion is an album he has wanted to make for a long time (and by no means his last — he's already thinking about recording his next one). He puts his roadhouse stamp on Lloyd Price’s “Stagger Lee” and Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally,” adds a dash of elegance to the R&B staple “One Shot, One Bourbon, One Beer,” and goes all the way uptown for two songs associated with Ray Charles, “I Want a Little Girl” and “Hard-Hearted Hannah.”

The two key artists he features, however, are Hank Williams and Jimmy Reed, who neatly encapsulate the breadth of McClinton’s influences — the hardcore country singer and the laconic bluesman.

McClinton says Williams “transformed me,” and you can hear Williams’ influence in the economy and vivid imagery of McClinton’s writing, if not in his musical style. On Outdated Emotion, McClinton performs a whopping six Hank numbers — almost a third of the record — re-creating the original arrangements with a group of Williams experts led by guitarist and steel player Chris Scruggs. McClinton says he did the songs that way to experience the sheer joy of replicating the music.

“Every time I hear “Settin’ the Woods on Fire,” I can’t wait till it gets to the fiddle break because I do this [mimics playing the fiddle].”

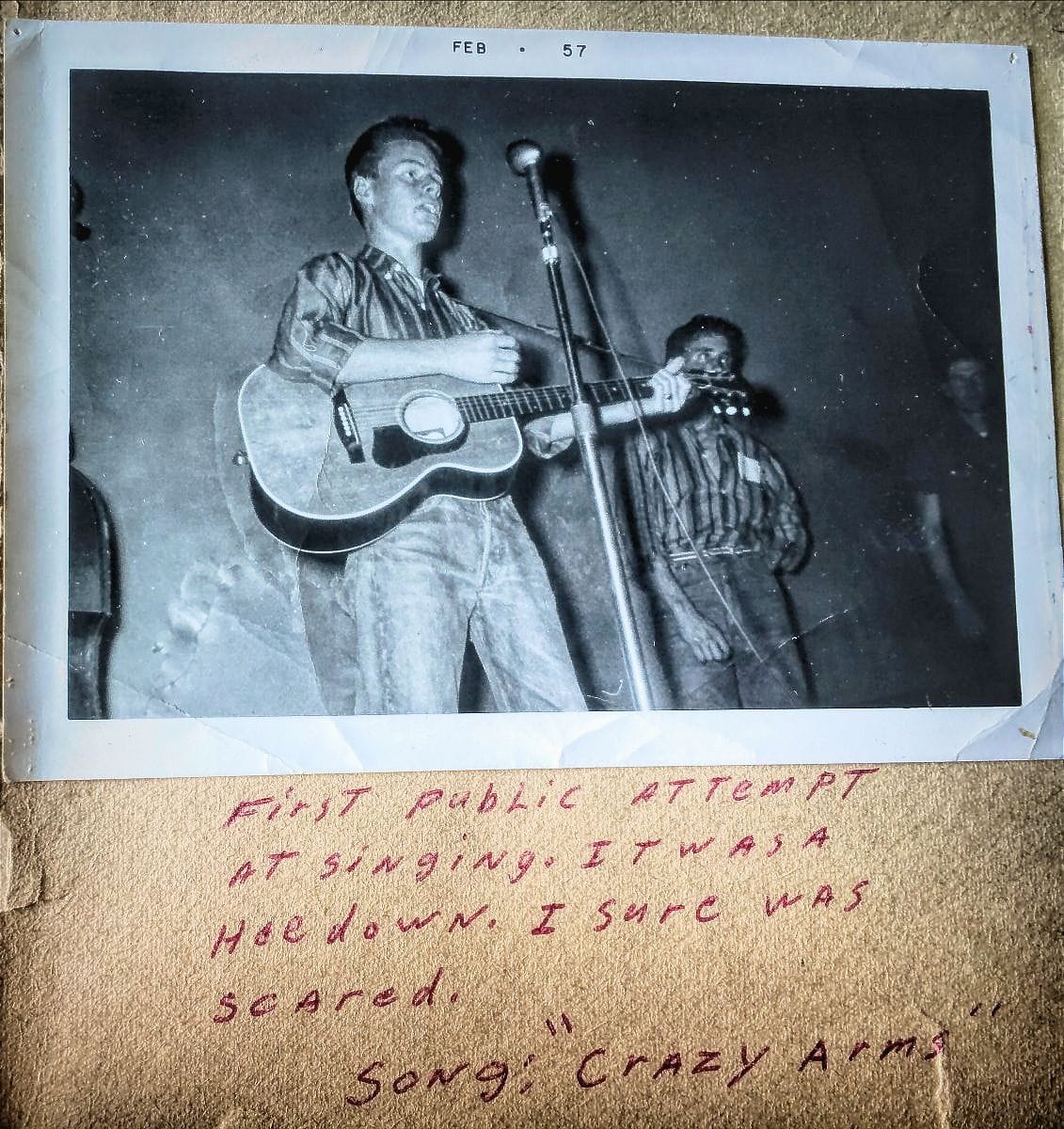

When he was starting out in Fort Worth, Texas, McClinton and his group often backed Jimmy Reed, the master of a style you could call “perfect imperfection.” It’s something that seems easy but is hard to nail down.

“Jimmy Reed is the pocket,” McClinton explains. “It’s that simple thing he does with the guitar. … Your body just starts moving to that. … It will make you smile, and you’re kind of dancing in place. You can’t help it.”

Finding that pocket for himself has helped McClinton define his own musical journey, and making Outdated Emotion has helped him relive the thrill of originally finding it. “This is where I came from and this is where I can get back to the pocket,” he says. “If you can find the pocket in a Jimmy Reed song, then you don’t need to know anything else in life.”

Scruggs and other collaborators also provide accompaniment on the McClinton originals “Two-Step Too,” which nods to his eclectic musical tastes, and “Money Honey.” Those songs, along with the self-penned “Sweet Talkin’ Man,” “Connecticut Blues,” and “Call Me a Cab,” are quintessential McClinton, exuding street-wise color that makes him both hip and down-to-earth.

Helping the singer find the pocket on much of the record are Kevin McKendree, his longtime keyboardist, and son Yates McKendree on bass and sometimes drums. It gives the arrangements a raw, stripped-down vibrancy.

McClinton says the selections on the album represent just some of what fired him as a youth. What also had a profound impact are what he calls “war songs,” music from the ’40s by the likes of Frank Sinatra, Lester Young, and Teddy Wilson.

“To me,” he says, “I’ve got to have a ’40s playlist every day or I can’t get my shit straight.”

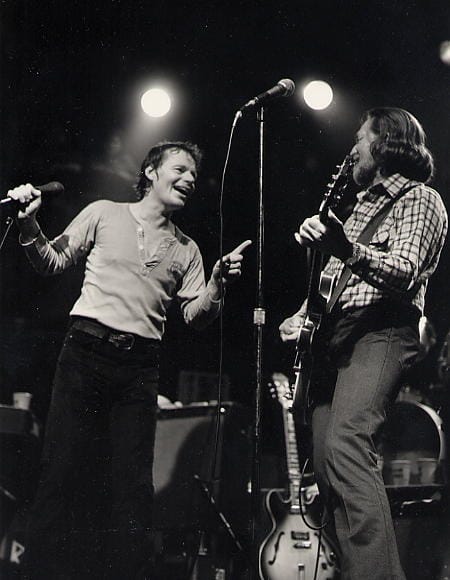

Back in 1962, when he was touring England with Bruce Channel after playing harmonica on Channel’s hit “Hey Baby,” McClinton gave some harmonica tips to John Lennon.

“We were all going to change the world,” he remembers. “That’s the way I’ve been my whole career. It’s not something I decided, it’s just a fact, in my mind. I’m still going and I’m still making good records. I’m living the life, you know. …

“What I’m doing is what I do, and I do it better than anybody, and that ain’t gonna change.”

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GgIg7ZUEDEM[/embed]

Comments ()