Who knew that Bob Dylan was such a hoarder? Until 2016, when details about the contents of his personal archives began to emerge, it’s unlikely that even the most ravenous Dylan scholars had any idea of just how much stuff he’d held onto over the years. It was certainly a surprise to Steven Jenkins, the director of the newly opened Bob Dylan Center.

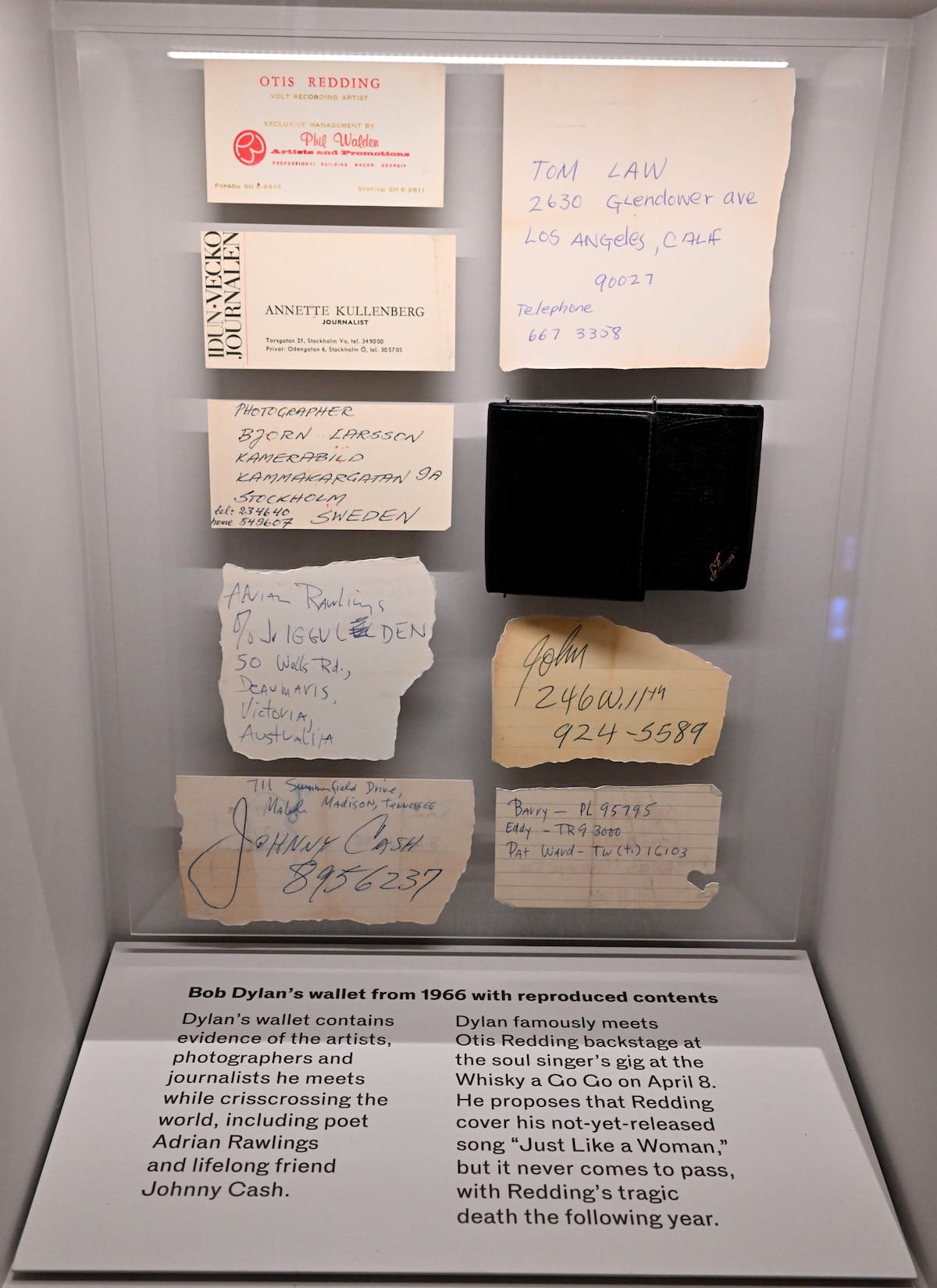

“For a guy who’s always said, ‘don’t look back’, Dylan appears to have kept everything. He could have tossed it all away or left it for others to sift through after he’d gone. But he didn’t do that. He kept all of this stuff … notes, scribbled lyrics, phone numbers, and old posters. Personal keepsakes of all kinds. It was all in boxes, desk drawers, and stuffed away at various residences. But, you know, I guess we reach a certain age and our acquisitive instincts die. We look around us and wonder what to do with everything we’ve accumulated.”

At first, Dylan surprised many people who expected that his archives would find a home in his hometown of Hibbing, Minnesota, or in New York City by opting to sell his collection to the George Kaiser Family Foundation based in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The result is the Bob Dylan Center, which held its grand opening celebration last weekend and is now open to the public.

It’s a good fit for Tulsa, Jenkins says, citing the town’s Woody Guthrie Center and other cultural sites.

“It’s no accident that we’re on the same block as the Woody Guthrie Center. We exist together under the umbrella of the American Song Archives,” Jenkins says. Dylan’s love of Guthrie and his acknowledgment of following in that tradition is well documented, and so Dylan visited the Guthrie Center and felt that it all made sense. It’s like he recently said, ‘The coasts are terrific and there’s lots of vibrations there, but I like the hum of the heartland.’”

From the moment I arrived in Tulsa for the grand opening, it was obvious that Dylan’s decision to locate his archives in the city has likewise struck a chord with the people there. The city as a whole rose to the occasion as they, along with the Center staff, pulled out all of the stops for a gala weekend that would culminate with the official opening and ribbon cutting ceremony on Tuesday.

At the opening night reception, donors who had paid thousands of dollars to attend mingled with journalists and members of the local arts community to sip on Heaven’s Door Whiskey while they watched the world premiere of the remixed “Subterranean Homesick Blues” video. Three nights of music followed, with inspired performances from Mavis Staples, Patti Smith, and Elvis Costello.

But as much as I enjoyed the weekend’s festivities, I often found it difficult to reconcile these well-heeled and erudite celebrations with an artist who’d purposely remained so elusive and had resisted classification for more than six decades. As a very young man, Dylan offered fluid and often conflicting accounts of his biography, telling reporters that he’d run away to work as a carnie at the circus and learned to play the blues at the feet of an old blind musician. The rigors of academia and conventional truths had never held much interest for him.

So how do you go about creating a permanent home to commemorate the work of an artist who’s never been comfortable with examination of his creativity or any speculations about his personal life? It’s a matter to which Jenkins has obviously given a lot of thought.

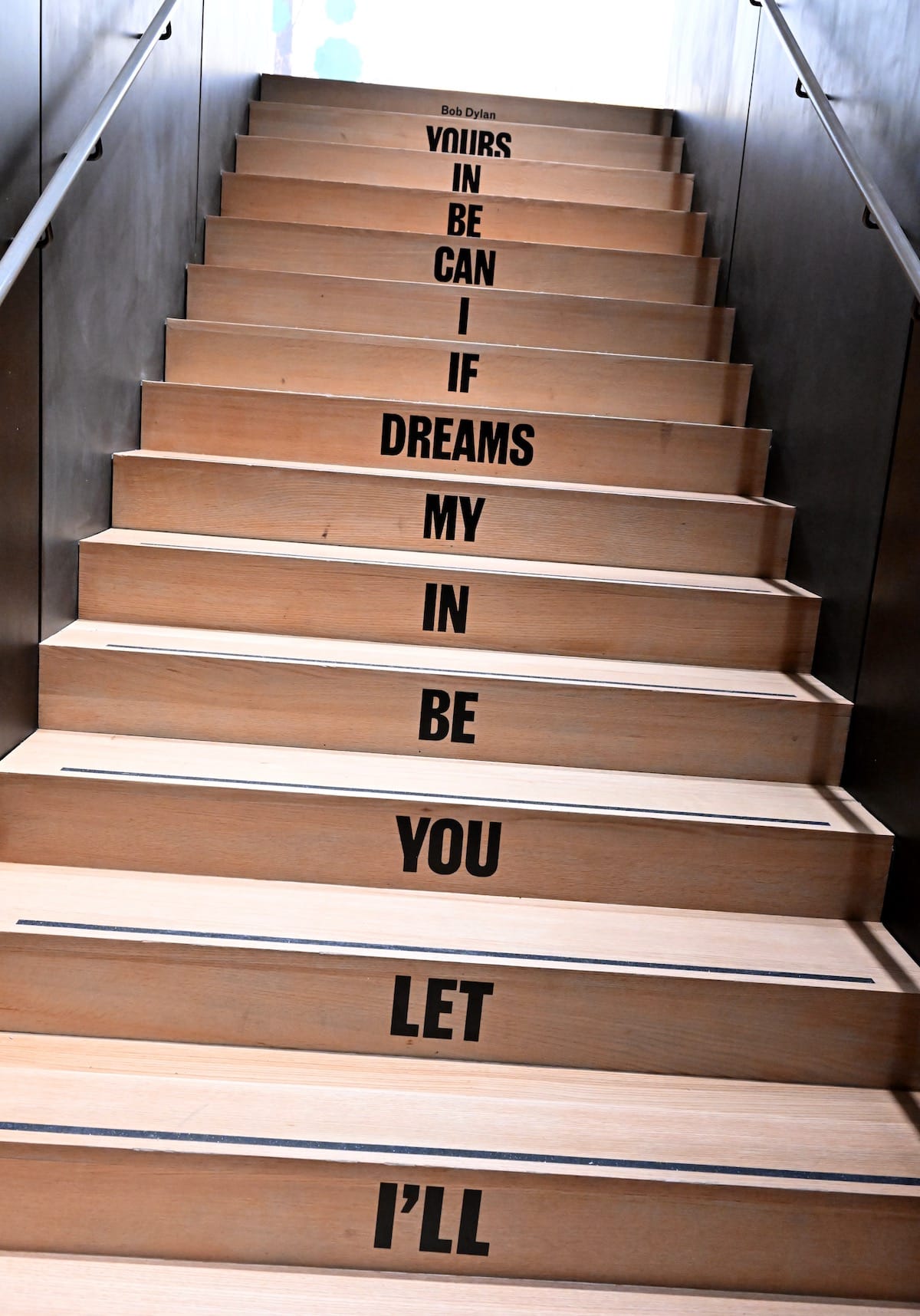

“Not to split hairs, but we are deliberately a center as opposed to a museum,” he explains. “For me, this implies more of a two-way dialogue. We wanted to do something more open-ended that fits the man at the heart of it. There is an eternal elusiveness about Dylan. Try as we might to get to the bottom of him, he’s always going to remain out of reach. We will always be chasing after him. It’s in that spirit that we present the materials in the archives.

“For example,” he continues, “we can now pinpoint exact recording session dates. We know that Dylan and a certain cast of characters played on a particular track. A lot of this has been well documented before, and if we can verify facts that were previously unconfirmed, that’s the job of an archive. We’ll provide the context for the scenes in which those facts came to be. But what we don’t want to do is try to pin down any particular meaning. It’s not for us to say that because we’ve got a hundred thousand items that used to belong to Bob Dylan, we can figure him out at last. Where’s the fun in that? Why reduce this endlessly expansive and myth-making artist to something where we can somehow say, ‘Now we’ve got you’?”

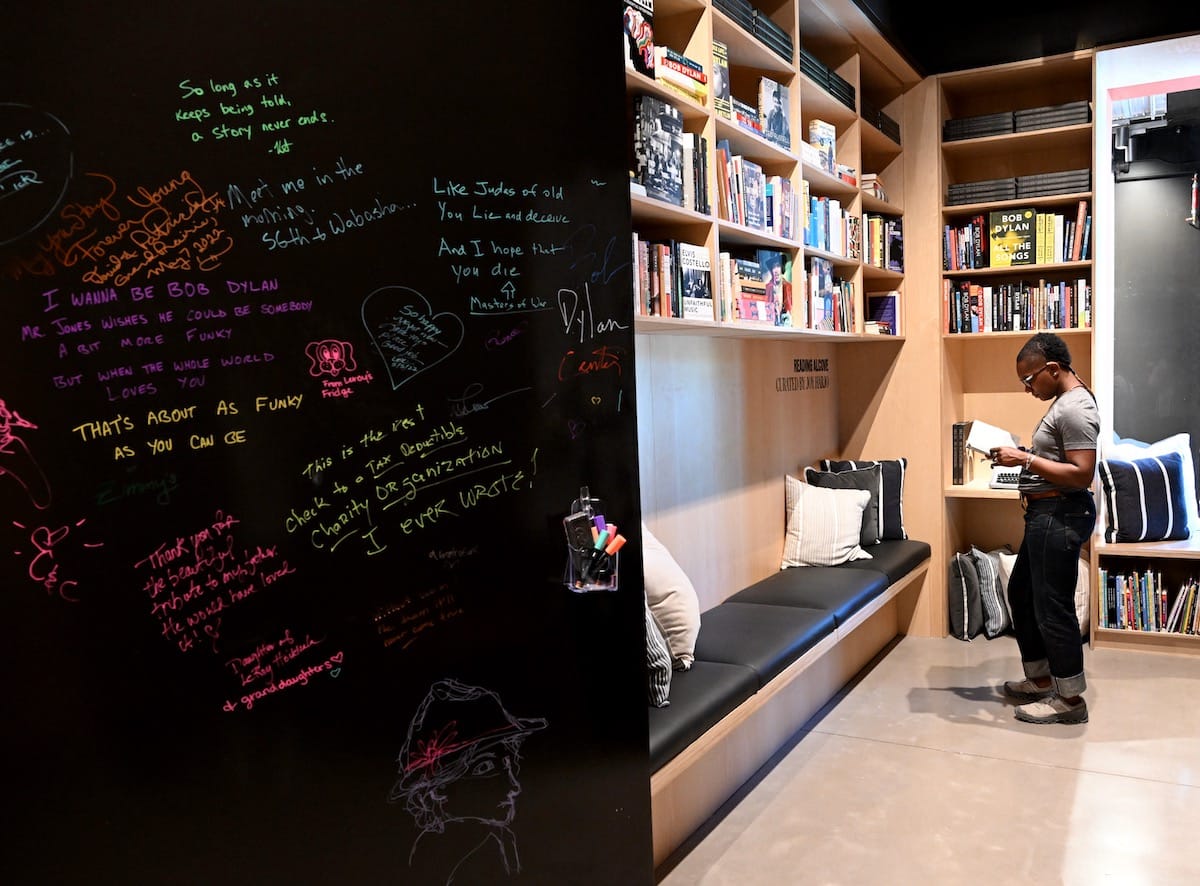

With that in mind, the material on display is designed to pose questions and provide contexts from which to appreciate Dylan’s output. “We’re not really interested in memorabilia as such,” Jenkins says. “If you want memorabilia, you can go to a Hard Rock Café.” The focus instead is “to offer a vista from which to explore Dylan’s creative process.”

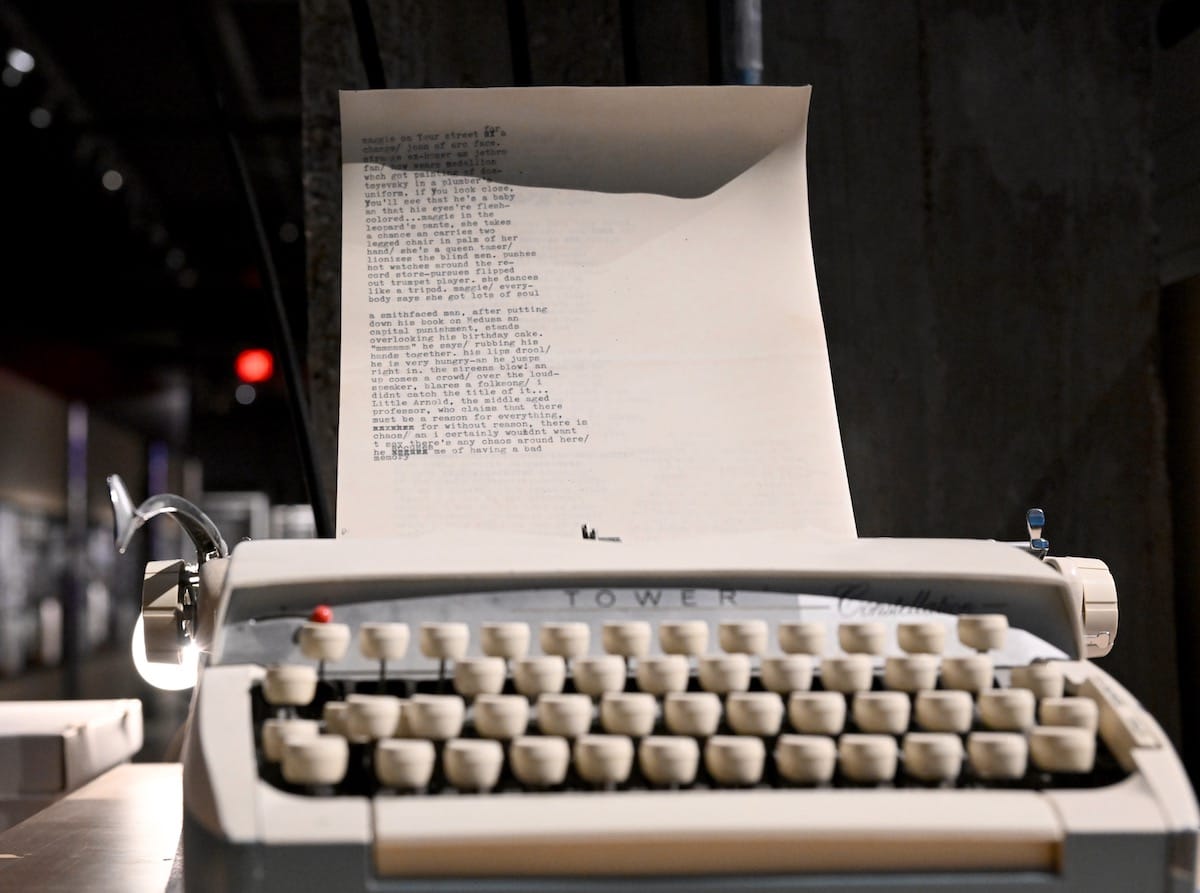

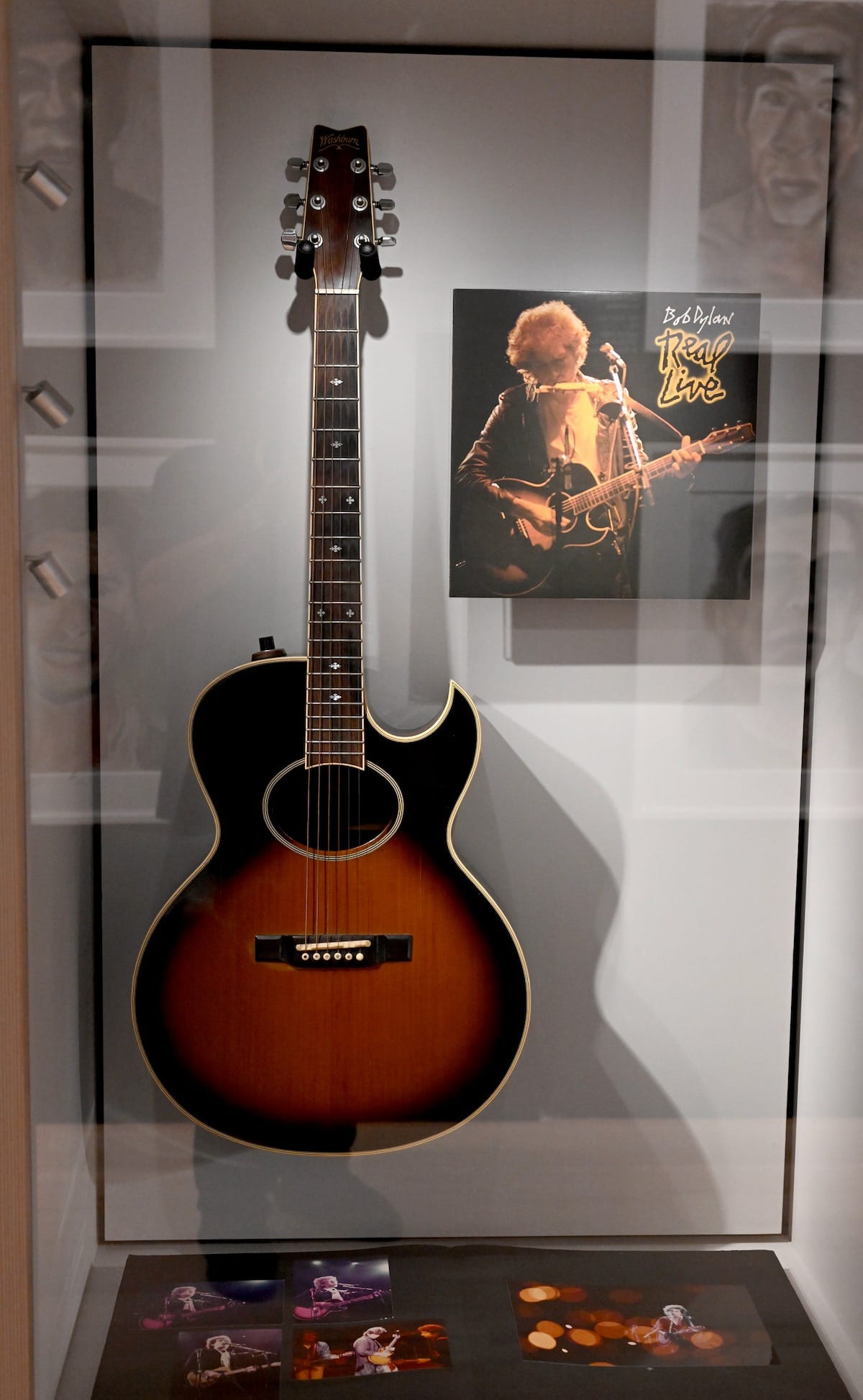

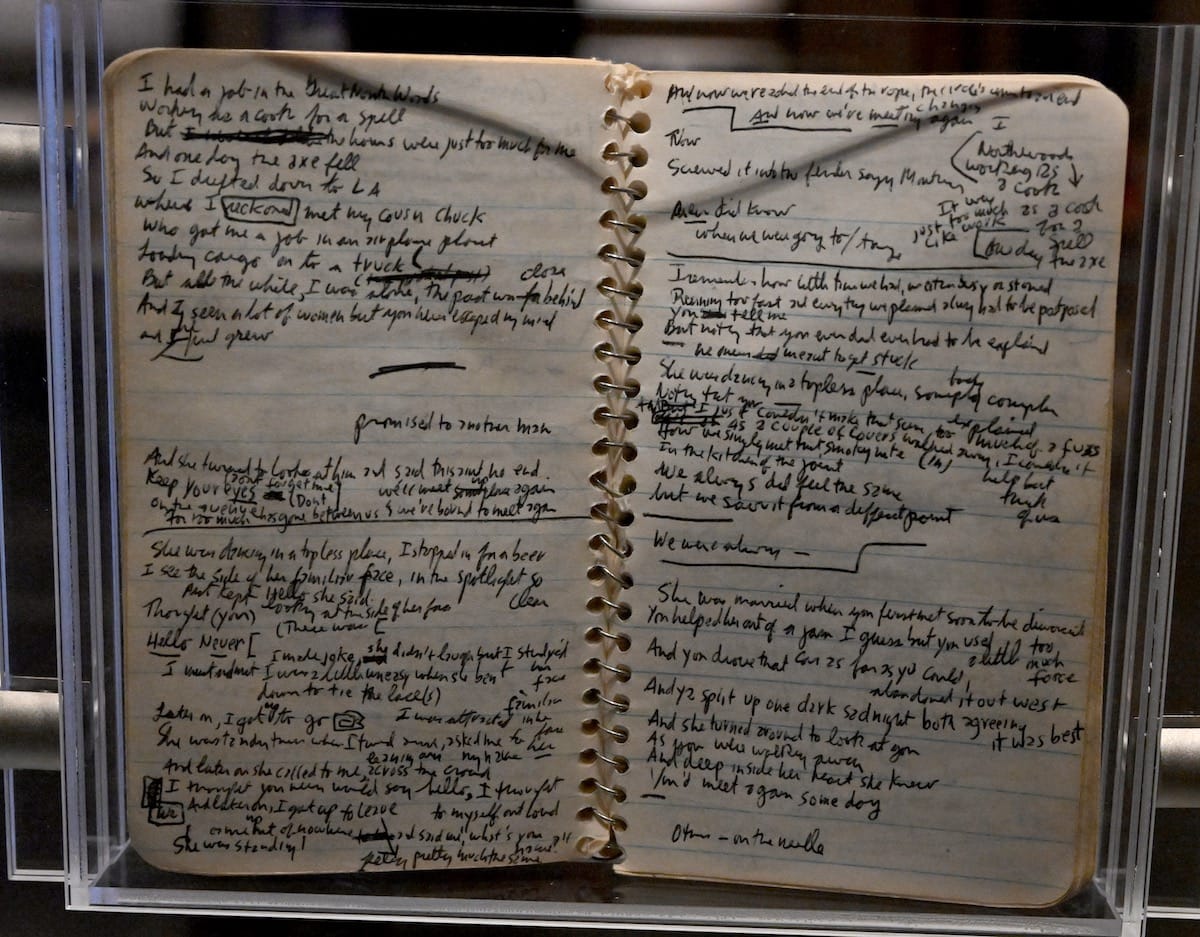

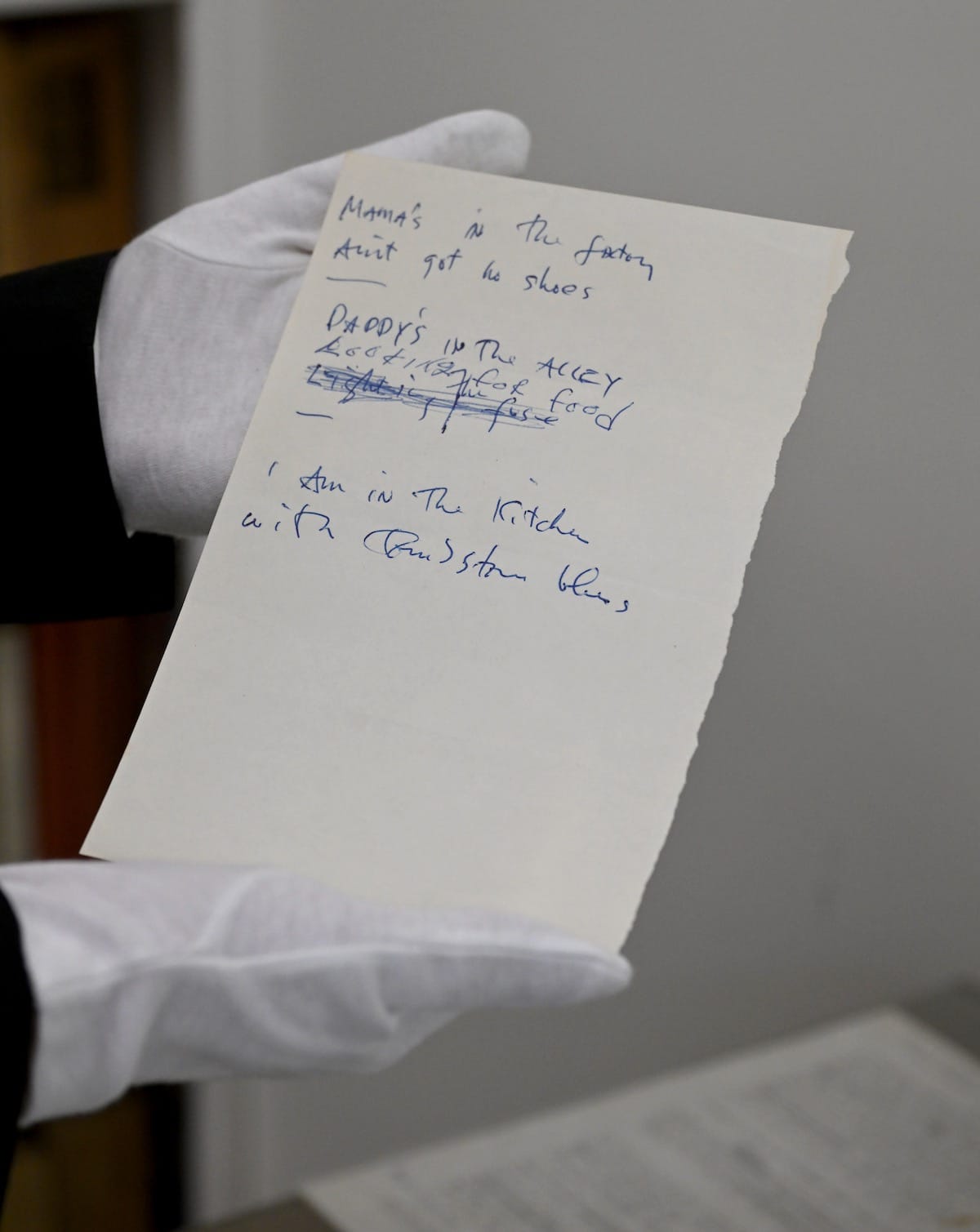

For visitors who want to do that, the most captivating aspect of the museum will undoubtedly be the central gallery, which presents a variety of materials from notebooks to instruments that relate to the creation of six different songs: “Not Dark Yet,” “Chimes of Freedom,” “Like A Rolling Stone,” “The Man in Me,” “Tangled Up in Blue,” and “Jokerman.” The handwritten lyrics, the scribbled chord changes, the famous notebook for “Blood on the Tracks,” and the typewriter used to compose on go far beyond a presentation of simple memorabilia. It is enlightening, for example, to scroll through interactive touchscreens to view the various iterations of the lyrics for “Jokerman” as they evolved over weeks and months. Visiting the recreated recording studio adjacent to the central gallery, it was heartening to hear someone of Dylan’s caliber struggle with “Most of the Time” as it progressed from an awkward demo where he stumbled and tripped over syllables to eventually arrive at the graceful, ruminative masterwork that became one of Oh Mercy’s most enduring songs. The archive’s insightful presentation offers a portrait of a musician applying his craft as he homes in on just the right word and phrasing for a song.

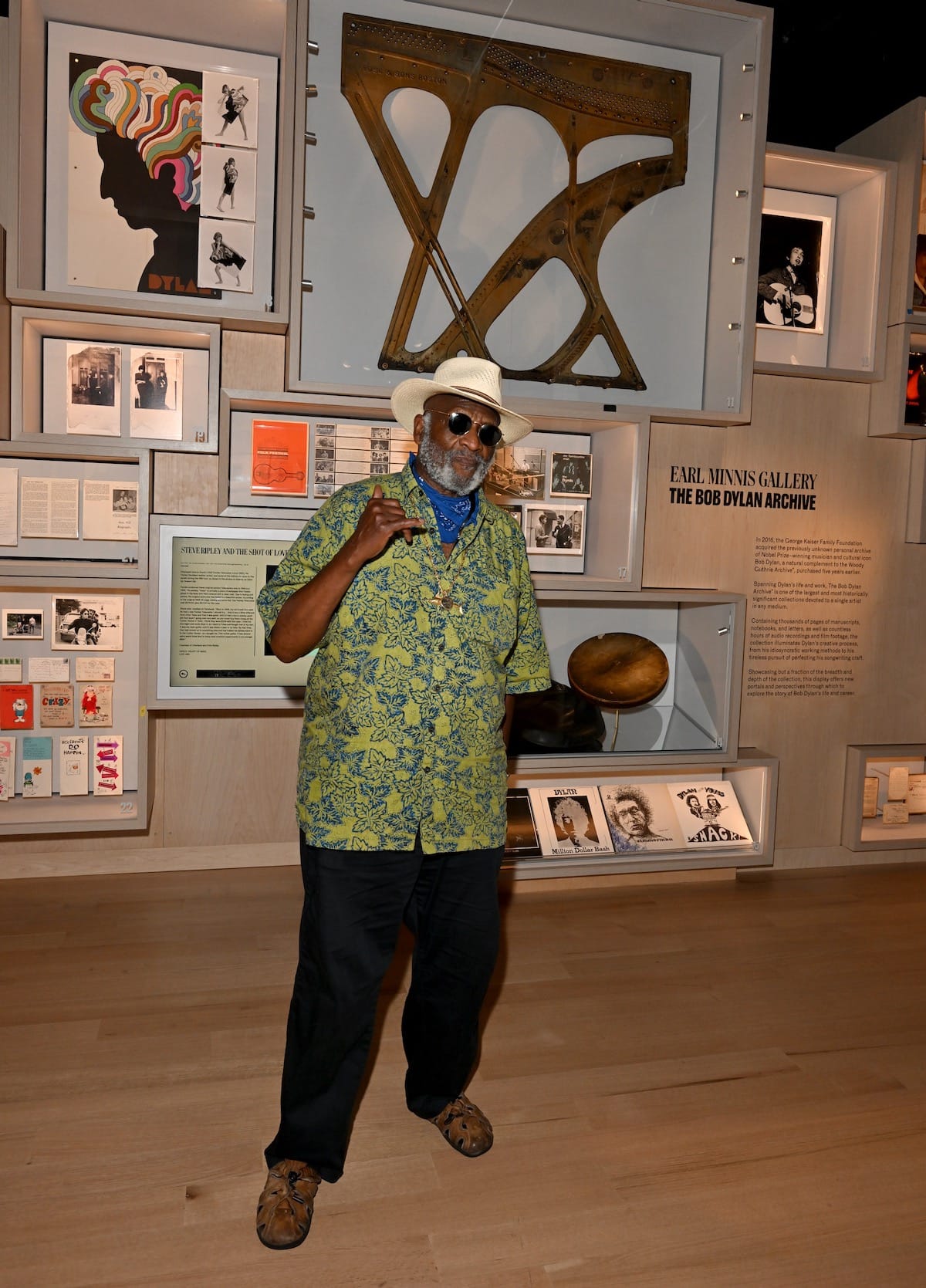

But those who love memorabilia shouldn’t worry. The Center has no shortage of fascinating objects and artifacts on display for visitors to pore over. From the jacket Dylan wore at Newport when he went electric to Christmas cards from the Beatles and Johnny Cash’s hastily scribbled phone number, there’s enough eye candy to satisfy the most avid fan and collector. Similarly, the second-floor archive wall features a rotating showcase for dozens of objects, like album cover designs and Rolling Thunder tour jackets, selected from the 100,000 or so items housed at the Center.

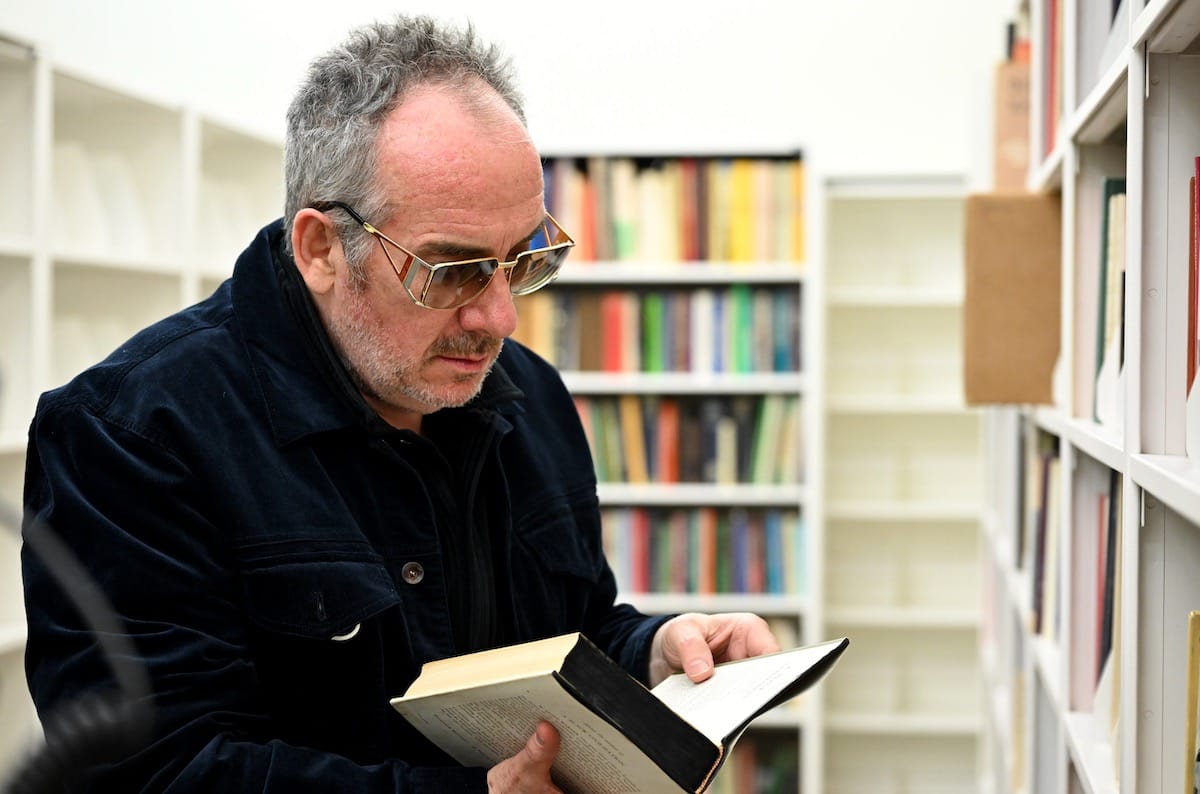

Jenkins expects that an array of guest curators and artists in residence will contribute to the Center’s evolution. At the moment, a jukebox featuring 160 songs selected by Elvis Costello plays subtly in the background as visitors stroll the galleries. Every so often, other artists will reprogram the jukebox. The photo gallery that currently features the work of Jerry Schatzberg, the photographer who shot the iconic photo on the cover of Blonde on Blonde, will feature ongoing exhibits that complement Dylan’s journey.

The Center doesn’t offer much, however, for those wanting to learn about Bob Dylan, the private individual and human being. “The emphasis is much more on his creativity, rather than, say, the details of his bitter divorce,” Jenkins says. “All that stuff is out there, but ultimately I don’t know what that tells us about the artist. A hundred years from now it won’t matter.”

While it’s hard to predict what will or will not be important a century from now, at the moment Jenkins’ focus is on providing an enjoyable experience for everyone who comes to Tulsa to visit the Center.

“We want to attract everyone from serious scholars to the mildly curious. Those who want to go deeper can. The complete archives are available to researchers by appointment,” Jenkins says. “If we’ve done our job right, we’ll hit visitors on many different levels. We’ll strike the right balance between rigorous research and accessibility. We want people who don’t know a lot about Dylan to have a great time here.”

The question looming in the background the whole time I was in the Center was whether Dylan himself had set any parameters for how the Center would present his work.

“We asked him if he wanted to make a metal gate for the entrance, and he came up with a wonderful piece that greets visitors as they come in. But, beyond that, he’s just told us to do what we need to do,” Jenkins answers. “There’s an implied trust in our stewardship of the material.”

I wondered if Dylan was tempted to pop in when he passed through Tulsa a couple weeks ago on his Rough and Rowdy Ways tour. He did not, Jenkins reports, though his longtime bass player Tony Garnier paid a visit.

“We kind of think that all of the hubbub surrounding the opening will die down and we’ll just be doing our thing here and someday at 4:30 in the afternoon on a rainy Thursday, he’ll walk in,” Jenkins muses.

“Of course, he knows that he has an open invitation. But when he was in town recently, the night before he played the Tulsa Theatre, he went to the opening night of our Minor League Baseball season. He told someone connected with us that he had a fun time at the game. So how can we argue with what he wants to do and what his idea of a good time is? In the end, we have our job to do and he has his, and you just kind of have to let go of any expectations. … We don’t think about whether Bob is watching us. We just try to do his work justice.”

Our friends at Folk Alley have updated their Classic Folk stream with a wide range of Bob Dylan songs, performed by him and by others, to mark the Center's opening and Dylan's 81st birthday on May 24.

Click on any image below to enlarge and view as a slideshow.

Comments ()