In what is likely Shakespeare’s final play, The Tempest, Prospero, the great magician who has controlled much of the play’s action, reminds us of the razor-thin line between our waking life and our sleeping life: “We are such stuff / As dreams are made on; and our little life / Is rounded with a sleep.” Of course, the playwright is hardly the only one who recognized the human propensity to sublimate wishes and desires into a state where everything can be attained and nothing can be lost, except in the waking from sweet sleep. The beauties and terrors of the dreaming state fill the texts of Western and Eastern literature. In the Bible, Joseph’s dreams win him a new job in a foreign regime and also foretell the demise of that very regime. Biblical prophets receive their calls to their vocations in dreams. In Hinduism, the state closest to nirvana is the deep dreaming state of meditation.

No wonder that some of our most popular songs sing of dreams frustrated, dreams deferred, dreams shattered, dreams interrupted, and dreams come true: “Dreaming My Dreams with You,” “All I Have to Do is Dream,” Dream Lover,” “Dream Weaver,” “Dreams,” “Dream On,” “Runnin’ Down a Dream,” “Daydream Believer,” California Dreamin’,” “Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This),” “I’ve Got Dreams to Remember,” “Daydream,” and “Dream Police,” to name only a very few.

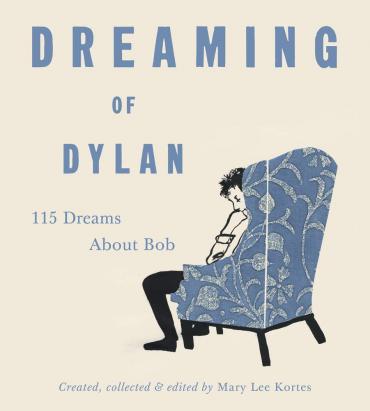

Now, in her Dreaming of Dylan: 115 Dreams about Bob (BMG), musician and author Mary Lee Kortes has compiled and edited a visually stunning and dreamy collection of, well, dreams that feature Bob Dylan. Kortes opens the compilation by describing her own dream of the enigmatic poet of our souls; recognizing that others, too, must have dreamed of the tangled-up-in-blue bard, she put out a call for dreamers and their dreams: “I dreamed I had dinner with Bob Dylan in a small dark restaurant with brick walls and candles. The warmth in his eyes was a guide, a magnet. Without words, he let me know he liked me and my music, and, in that silent approval, encouraged me to keep going. Two kindred souls, one just happened to be an icon — an archetype — and one a not-quite-complete unknown. I dreamed I had dinner with Bob Dylan many times. One morning it occurred to me that I couldn’t be the only one in this world dreaming about him … . So I started posting a call, here and there, for dreams of Dylan … . Collecting and visiting these dreams of Dylan has been a wild pleasure ride. They are alternately touching, funny, puzzling, wise, crude, tender, frightening, and romantic … . As he said himself, ‘I’ll let you be in my dreams if I can be in yours.’”

The individuals who share their dreams in the 115 dreams that she collects in the book — whose title plays on Dylan’s own “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream” from Bringing It All Back Home — range from musicians such as Patti Smith and Jimbo Mathus to plumbers, dentists, attorneys. Stephen Fox, an artist and film producer from Santa Fe, New Mexico, for example, dreams that he’s busking on a street corner, playing his own version of Dylan’s songs, when a black Bentley limousine pulls up. Dylan jumps out of the back seat of the car and says, “No, that’s not how the song goes; let me show you how the chords change.” Fox hands Dylan his guitar and Dylan proceeds to break the A string. When Fox suggests that he can change the string, Dylan does him one better and gives Fox an old Martin Dreadnought: “I like what you’re doing, so how about this? This might make you real happy.”

Warren Zanes, Tom Petty’s biographer, describes Petty as a “first-rate storyteller who told Dylan stories with great relish, affection, and wry humor.” Of course, Zanes points out, Petty would often tell a Dylan story and then tell Zanes that he could not use it in the biography. Zanes goes on to describe a dream in which Petty leads him down a series of hallways backstage in a “nondescript arena” to door after door in search of Dylan so that Zanes and Petty can ask Dylan’s permission to use some of the stories that Petty’s been telling his biographer. The ending of the dream is both terrifying and hilarious, and typically Dylanesque.

Salvatore Licciardello, from Italy, shares a short dream: “I once dreamed Dylan was without legs, and he sang in a small village with two cords of wood under his shoulders (like a paraplegic or paralytic).” New Jersey music director Pete Johnson shares his dream of walking in the woods with Dylan, “like old friends,” and when they reached the road, they “shook hands and went home in different directions.” One dreamer, whose name is withheld, shares a dream of sitting between Dylan and Charles Bukowski at a bar; the dreamer orders a Coca-Cola because just two months earlier he has become sober after years of alcoholism. Dylan takes the stage, and Bukowski tells the dreamer that Dylan is going to sing a song just for him; the dreamer cannot make out the lyrics or the music. Disappointed, the dreamer returns to the bar and orders a cocktail. “Before it arrived, I looked up, and Dylan was gone. I got up and left the bar in terror. Woke up. Twelve years later, I haven’t had a drink.”

Dylan invited Kortes to open shows for him after he heard her band Mary Lee’s Corvette released a live song-for-song interpretation of Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks. In Dreaming of Dylan: 115 Dreams about Bob, Kortes provides a surrealistic pillow on which we can lay our heads and allow the bard from Hibbing to carry us down to lands unexplored. Reading Kortes’ book transports us into that borderline territory where dreams infuse our waking lives. One thing is for sure; her book confirms that we create our own visions of musicians as much as they construct — carefully or not — visions of themselves they’d like us to embrace.