E(a)rnest in Town and Jack in the Country: Bob Dylan On Tour in England

The Bank Holiday weekend at the end of April is everyone’s favorite in England. Not only does it mark the heart of springtime but heralds the popular holiday kept for many centuries on the island: May Day. Celtic and Anglo-Saxon fertility festivals coincide with Morris dancing, crowning May queens, besporting oneself around a maypole in the village green, and other May-morning festivals — the largest of which is in Oxford. This year, May Day was on a Monday, and there was much rejoicing at a long weekend settling around the celebration.

London was beautifully quiet from Friday, April 28th on. There were fewer cars, for a mercy, in the normally woefully snarled streets; museums had lighter traffic, too, for even the keynote shows of the season — David Hockney at the Tate; American art of the 1930s at the Royal Academy. Tickets were available for some sold-out, soon-closing plays, like the revival of Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, starring Daniel Radcliffe and Joshua McGuire on the same stage at the Old Vic where, fifty years ago, the play had its London première.

Stoppard was in London during the holiday weekend; but he was not, at least not every evening, at a play. He was at Bob Dylan’s first night at the London Palladium on Friday, listening to….well, here. While it lasts on line, have a listen for yourselves. The sound quality is unmatched, from every note of Stu Kimball’s “Foggy Dew” intro to the final “do ya, Mister, Mister Jones?” in a version of “Ballad of a Thin Man” with some contemporary lyrical updating (listen for it).

Dylan and his band at the London Palladium, Friday, April 28, 2017. Thank you, Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.

Dylan was, in his London concerts, cool and controlled. Saturday night the set list was the same. On the last night, Sunday, April 30th, one might have thought he might have responded a bit to the revelling May-Day spirit in the crowd. Not visibly, he didn’t. Despite a light rain in the Mayfair streets, people were happy on the holiday night, with no work to go to on Monday and the reds and golds of the old palace of a theatre around us. There was a lot of talking and singing along during the show, though folks silenced each other during the surprises, like “To Ramona” and a fresh, sprightly, swingy “That Old Black Magic.”

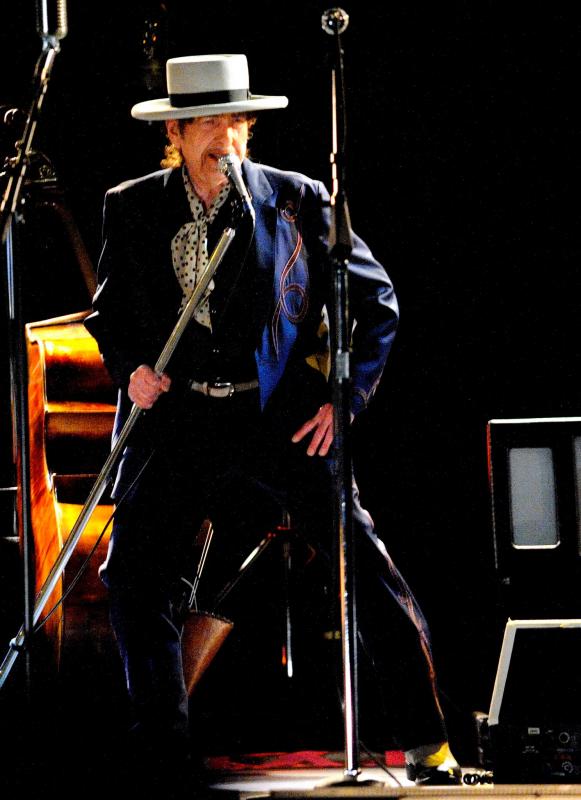

Dylan in full crooner cry, London, April 30, 2017 © Andrea Orlandi

No one wanted to leave at the end; cellphones came out in force, and the stage and le tout London — I didn’t see Stoppard, but Bill Nighy was back for another show — were copiously photographed. The crowd was tweedy and older, on Sunday, literate and literary, there as much to hear the Nobel Laureate as any of the many multitudes Bob Dylan contains. We compared notes on the changed lyrics we thought we’d heard, and laughed over favorites. Outside, stacks of damp merchandise on the sidewalks and proper black cabs awaiting customers shared the space with people posing under the marquee. I walked back to my room on a blooming springtime square by way of New and Old Bond Streets, past the show of Dylan’s silkscreened American scenes that had just opened at the Halcyon Gallery.

Skip forward a few days, hop in the car and, being careful on the wrong side of the road, head south-by-southwest. You will drive through heavy traffic, and then onto rural high plains, green and gold this time of year with fields and fields of rapeseed. Keep going, and the gold takes on a different cast and sheen: gorse, or furze. The fields are smaller and thicker, dark and ragged-edged. Hills climb higher. Dorset takes on its wild-weald feel that Thomas Hardy imagined memorably, not so long ago, in his great late 19th-century novels. Peel off the main roads and enjoy those like the B3078, wending through bracken and ferns and deep hedgerows that suddenly give way to little villages that all seem to have Wimborne in the name. Stop at Wimborne Minster to see the sturdy, radiant Saxon church where Aethelred I, King of Wessex, is buried, and one of the world’s most fantastic libraries is located; just try making off with one of their volumes. Continue on to the point where you fetch up on the coast, in Poole, and turn left, following its ancient harbor around to Bournemouth. Literally at the mouth of a bourne, or brook (in Scotland, they’d say burn), the town grew from a fishing village to a seaside resort in the 1800s. Today, Bournemouth is a large city with two universities, a football club nicknamed the Cherries since the early 1900s (whether because of their red-striped uniform shirts, or a nearby cherry orchard, is up for debate), a beautiful harborfront, and — right on the water, at the harbor — the Bournemouth International Centre. In this well-appointed and sublimely situated venue, on the 4th day of May, I heard one of the best Bob Dylan shows I’ve been to in the past twenty-nine years of going to them.

Dylan and his band in Bournemouth, May 4, 2017. Thank you, Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.

From the beginning, you felt it in the air. The crowd was eager and anticipating; many people I spoke to had heard Dylan before, but not for many years. Two men had been at the Isle of Wight, visible that evening as a bluer blue afar off in the slaty waters, for that immortal Dylan appearance with the Band. Most people there, though, it seemed, had never heard him at all. I sat in an excellent seat next to Lisa, who had driven up the Jurassic Coast from Lyme Regis, an hour west of Bournemouth, for her first Bob Show. At the end of “Desolation Row,” she turned to me in the applause and burst out, “Oh, he’s so good!” I could only nod, and smile, and keep clapping.

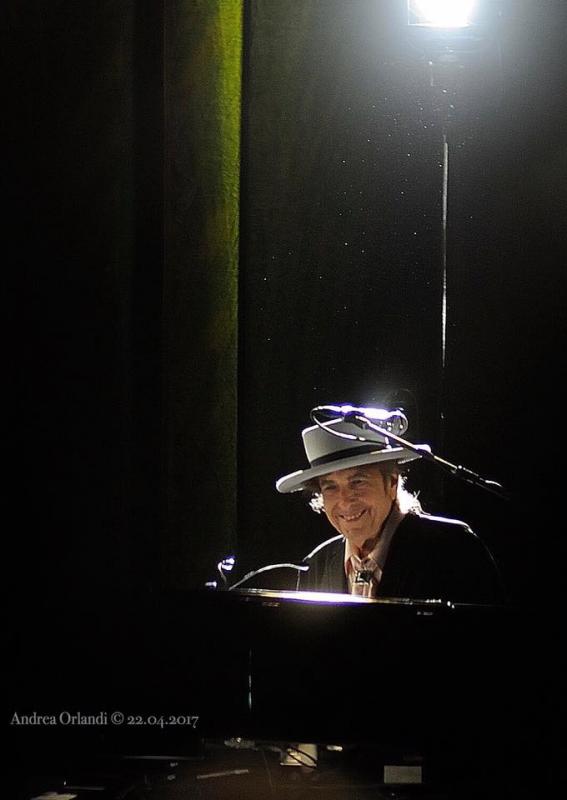

He was. He was superb. Dylan positively danced onto the stage, bobbing and weaving, looking around him and keenly out at the audience with interest and engagement. “I’m a worried man,” he proclaimed, but you could see he was the furthest thing from that. “Things Have Changed” was a rollicking romp, its dark lyrics delivered with a grin, literally, on lines like “Ain’t no shortcuts, I’m gonna dress in drag.” “To Ramona” was a three-beat pure waltz, Dylan’s voice swinging low on the end of the lines. Words shifted and slid, like three-card-monte cards: not the “strength of your skin” but “the touch of your skin.” He jumped from “On back to the South” to “From fixtures and forces and friends.” The liquid, jingle-jangle piano was a joy.

People jumped up to sway along with “Highway 61 Revisited.” George Recile’s drums threatened to overwhelm, at first, but the acoustics of the venue operated to smooth the sound into submission. “Come over here, girl, step into the light,” Dylan ordered the white-faced fifth daughter, and soared into the conclusion. The Dylan-Robert Hunter “Beyond Here Lies Nothin,'” from 2009’s Together Through Life, is a song Dylan has done regularly in concert since its debut. The harbor and ship imagery in its last stanza fit nicely into the sea air.

Dylan and the band then shifted gears to his first album of American standards, 2015’s Shadows In The Night. (Fallen Angels, 2016, and Triplicate, 2017, contain more of these standards). “Why Try and Change Me Now” seems, every time he sings it, a direct address to all of us. The only person who’s ever going to change Dylan is Dylan. If you were inclined to complain that he should just sing his own songs, don’t. He, and his band, are clearly enjoying the dickens out of playing these songs, many of them covered by fellow Columbia recording artist Frank Sinatra. Why has Dylan become Crooner Bob these days? Please. He’s always had that streak in him; think of his some of his best-known early covers of sentimental love ballads, and his own classics. “Forever Young” can be a rock and roll blast, or a hymn. It’s in the delivery. Dylan has said before how much he admires crooners like Rudy Vallée (remember how hard he pulled Nora Ephron’s leg, in 1965, about Vallée being “sexless”?) and Sinatra, and last year he paid a warn tribute to Tony Bennett for Bennett’s 90th birthday.

What type of singing can a performer — a male performer, notably — continue to do, over 70, or 80, or 90? There are two: folksinging (see Pete Seeger) and crooning (see Bennett). Dylan began his career as a folk singer. Though he has carried forward with him the styles of music that have made his own art, he doesn’t return to earlier versions of himself. Never say never, I suppose, but it seems unlikely (alas) that we’ll ever see him alone on a stage again with a harmonica in its rack, singing about little Maggie with a dramglass in her hand. Being a crooner appeals to him, and Dylan is not only having fun with the style these days, he’s doing it well. Crooning is all about phrasing, and Dylan is a master of the sung phrase.

He also likes to mix up the crooning with his own recent, sharp original songs. “Why Try To Change Me Now” gave way to “Pay In Blood,” one of the most stinging tracks on Tempest (2012). A swoony, tuneful “Melancholy Mood” and a standout “Stormy Weather,” with Dylan twirling the mic stand and vamping, prancing across the stage with it, were separated by the rocking, rolling “Duquesne Whistle.” And then Dylan looked back, with one foot firmly in the present, and an old-new “Tangled Up In Blue.” The rocking-chair rhythm of the arrangement made Dylan’s new emphases, and the words not on the Blood On the Tracks version that so many of us grew up with and are growing old with, stand out. He starts out in the third person, and shifted to “I” on “helped her out of a jam” this time. The “topless place” verse is gone, though the book of poems remain. My favorite change is “Yesterday is dead and gone / Tomorrow might as well be now.” Somehow it sums up Dylan’s sense of time: the future is always the present — and yesterday, even in its being denied, is always here too.

“Early Roman Kings” is a sassy, sexy burn-you-down of a song, thanks in large part to Muddy Waters’s “Mannish Boy” riff — thanks in turn to Willie Dixon’s “Hoochie Koochie Man.” You write a new song based in that riff, and indeed Dixon’s tune, and it has to be sassy and sexy. Dylan doesn’t disappoint. When he sings “I ain’t afraid to make love to a bitch or a hag,” and “I ain’t dead yet / My bell still rings,” the audience yowls right back. Similarly, in “Spirit on the Water” (also with, in patches, entirely new lyrics these days, after many performances since 2006), the last verse, unaltered, always brings yells and cheers: “You think I’m over the hill / You think I’m past my prime / Lemme see what you got / We could have a whoppin’ good time.”

“Desolation Row” was the revelation for me this night. I’ve heard Dylan perform it hundreds of times, but never like this. A plinky arrangement that sounds like a tack piano thanks to Donnie Herron and the band, and Dylan’s clear voice, pausing, interrupting the original phrasing to intensify it, amazed me. The words he sang, but nearly suppressed, entirely change the song. That “tightrope” is muffled ties the blind commissioner to a walker — the image completely different now. Someone says to Romeo, “You’re in the wrong room, my friend, you better hurry up and leave.” The “Ophelia” and “Einstein” verses are left out, and Dr. Filth appears early instead. I miss Nero’s Neptune, the Titanic, Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot — that verse was left out, too, which emphasized the final one even more after an instrumental passage.

“Soon After Midnight” is one of Dylan’s own original crooner numbers, with lyrics grimmer than anything by someone else that Crosby or Sinatra sang. The band, and particularly the guitars of Kimball and Charlie Sexton, shone on this one. They followed it with a skiffle-beat, ting-ting-ting punctuated “That Old Black Magic” during which they were all, clearly, entertained. Every time Recile raised his drumstick, I thought, “more cowbell” and giggled. Dylan downright camped it up, drawing out an exaggerated “aflame” and enunciating the fast words every bit as cleanly as he did on “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” The audience loved this one. “Long And Wasted Years” contains the line “Shake it up baby, twist and shout,” which went over well in England, and some new words to this new song. Among others, a whole changed verse: “My enemy crashed into the earth / I don’t know what it is worth / But he lost it all, everything he had and more / What a blithering fool he took me for.” The glide into a brief “Autumn Leaves” was a coda before the real ending.

The beginning of “Blowin’ In The Wind” sounded almost exactly like the start of “Soon After Midnight,” making an aural point to me that fifty years between them isn’t really so long. Donnie Herron’s fiddle echoed the series of questions as Dylan sang them. The final number, “Ballad of a Thin Man,” had so many lyrical changes and re-ordered or dropped verses that it was a perfect blend of a song you’d always known, and one entirely remade. I love the ending: “Well, ya crawl in the room / Like a camel and ya frown / You put your eyes in your pocket / You put your nose in the ground / There oughta be a law / Against you comin’ around / Next time you do, please remember, don’t forget to telephone….”

As the lights went up, and the band ranged across the front of the stage, Dylan rested his right hand on his hip and surveyed us. Then he held out both hands and received the applause. He might have thought about it, and then he grinned. Reports of his shows since, from the country shires, Northern industrial metropolises, and Celtic cities, have all been good.

Bob Dylan and his band continue a North American tour this June, beginning with three evenings at the Capitol Theatre in Port Chester, New York; dates are here.

All photographs from the 2017 European tour courtesy of and © Andrea Orlandi.

Editor’s note: Anne Margaret Daniel wrote about Bob Dylan’s Midwestern roots for the “Heartland” edition of our print journal last spring. You can read that article here. Please consider subscribing to get even more great music writing in our pages every quarter. Here’s where to start.