Everything you ought to dig about Harry Belafonte, authentic American folk activist

Don’t laugh at Harry Belafonte, the incomparable American/world roots folk musician and popularizer, for being caught on tv asleep or meditating last week. Laugh with him during his appearance with Steven Colbert which he amazingly turns into a genuinely musical and touching duet on “Jamaican Sunrise.”

Even Colbert gives it up to Belafonte, whose wit is quick. Indeed, at age 84 the man is a bundle of energy and sharp observation. He’s been busy promoting his autobiography My Song, basking in a profile burnished by the laudatory HBO documentary Sing Your Song and its accompanying album, and voicing support for Occupy Wall Street. Given all that, so what if he chills? What could be more mundane than waiting in your own home for an early morning interview with a West Coast network-affiliate tv station?

I interviewed Belafonte 14 years ago for a cover story in RhythmMusic magazine (I was then editor). I’d known his music since I was little, and had recently experienced mixed reactions to his acting in Robert Altman’s Kansas City,”

The Authentic Harry Belafonte at 70

When Harry Belafonte strides out onstage— probably every time he performs anywhere — he puts a skip in his step. A glint in his eye zooms the audience, laser-like, seeking a link directly to each of us. Or so one imagines, struck by the lightening charisma of this 70-year-smart man. Right now, as in his salad days during the first quake of late 20th century pop culture, Belafonte’s name, face, voice and talent looms huge among international crossover stars.

He’s at the Kennedy Center, introducing Salif Keita, Youssu N’Dour and other artists of Africa to the Beltway bunch who depend on a man of Belafonte’s reputation to bring them up-to-date. He’s on television, via PBS broadcasts and the video release of An Evening With Harry Belafonte And Friends by Island Records. It’s his first such U.S. tv special in 20 years, and the show’s soundtrack is his first live record in a decade. Island also has Belafonte in its distribution sights as he plans the debut albums of his own Niger label for 1998.

Belafonte’s in the movies, last year cast notably against type as an ultra-violent gangster-boss in Robert Altman’s Kansas City; he’s frequently photographed with his wife in newspaper and magazine society columns, and was profiled by Henry Louis Gates in The New Yorker. At the Marian Anderson Theater in Aaron Davis Hall of the City College of New York, up in Harlem, Belafonte recently reigned as a favorite native son and paterfamilias, mixing casually with a cast of friends and fellows including Tony Bennett, Diahann Carroll, ex-Mayor David Dinkins, Roy Hargrove, Letta Mbulu, Miriam Makeba, Joshua Redman, Max Roach, and his latest band, led by protégé-guitarist-bassist-vocalist Richard Bona of Cameroon.

They’d gathered to go wild about Harry and give him the first Harlem Renaissance Award, during a concert gala sponsored by the Lincoln-Mercury division of the Ford Motor Company and AT&T. He addressed them from the stage, as natural under the bright lights as if sitting in his living room.

“My mother, a domestic worker who was originally from Jamaica, used to walk past this great school with me almost every day,” remembered Belafonte, “and she’d say, ‘Harry, one day you gotta go there.’ I never got the chance — I left school when I was 15—but then years later, the great Ron Carter, jazz bassist and music professor, put me in line for an honorary degree.”

To protect her family from a wave of Depression-era crime, in 1935 Harry’s mom resettled them in Jamaica (the Blue Mountains, St. Anne’s and Kingston). Belafonte found little opportunity returning to Harlem in ’40, eventually joined the Navy, got married, and discovered the theater. Proceeds of this Renaissance award he’s initiating by accepting are dedicated to helping the children of Harlem recognize theater as a right — or, as Belafonte says, “We hope to bring some smiles to America’s face.”

For millions of American baby boomers, Belafonte has cast just such a magic spell since our childhood. He’s the folk singer as superstar, a cultural icon on par with Sinatra or Presley, whose recording Calypso (RCA) of 1956 was The Harder They Come of the Eisenhower Administration — if not its Thriller.

The first long playing album ever to sell a million copies, Calypso

He was something other than a singer or even an entertainer by then, and far more personable in image than most symbols — he was somehow awaited. Catch Carmen Jones, Otto Preminger’s all-black 1954 update of Bizet’s opera with libretto by Oscar Hammerstein, on late night-TV (it’s in recent rotation) and watch Belafonte as the airman-protagonist, singing voice dubbed yet himself indelible: heroically handsome, abrim with passion and dubious honor, suffering the anguish of betrayal with the pique of a teenager, the most likable if tragic of illusion-doomed guys.

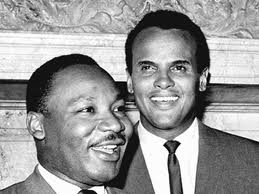

In fact, Belafonte is a gifted singer, who’s strong suits are his gifts for interpretation and delivery, his conviction and ultimate sunniness. He believes himself a teacher, and seems to have been a prophet, too. His intents and integrity have been scrutinized and assailed, but his efforts — especially as they superseded commercial activity to serve as vocal, moral and financial support of Dr. Martin Luther King’s civil rights initiatives, the USA for Africa’s “We Are the World,” UNICEF and his friend Nelson Mandela’s negotiated revolution in South Africa — bear all tests, including time.

If a male chorus sometimes renders Calypso as credible as “The Legend of Davey Crockett” or a campfire scene with the Sons of the Pioneers, Belafonte’s realizations of collaborations with Juilliard-schooled Irving Burgee (aka Lord Burgess) and lyricist Bill Attaway brought beguiling authentic qualities of African diaspora musics to the public ear: hand-drum fundamentals, montuno piano passages, kwela-style penny-whistle solos, guitar obligattos (by Millard Thomas), and the universal joy of expressing, thus eluding, outwitting and transcending pain. If Belafonte’s music in the ’50s had arrangements and production touches that in hindsight sound designed to soften, “beautify” or simply sell, it had also undeniable melodic hooks, sly humor in its verses, and a point of view that spent no energy on disguise.

“Paul Robeson, my mentor, once said to me, ‘Harry, get them to sing your song, and they’ll want to know who you are.'”

After four decades, “Day-O” has won the warmth and dignity Belafonte finds in it, and whether you’re sitting in a banana boat, in a theater seat, or on your bed staring at the tv, you almost have to (that’s okay, you’re urged to) sing along.

“The PBS special represents the end of a cycle,” says Belafonte from his hotel room in Honolulu, at the start of a week-long spring Pacific tour. “I wanted to introduce Richard Bona and two or three of our current songs.” He gives Bona, music director of his hip world-beat band, a solo spot in the middle of his show: under purple lights, wearing a derby, Bona thumbs deep, soft bass paths, then lets his voice loose with fantastically precise rhythm, diction and drive a keening stream of non-English phonetics. Bona’s also been gigging with Joe Zawinul’s Syndicate; and recorded Spaces II (Shanachie) with Billy Cobham, Larry Coryell and Birelli Lagrene.

“There’s a new direction in which I’m headed,” Belafonte insists. “I’m going into workshop for a few months to prepare new material, in new ways, and come up with some new configurations. Richard and Jake Holmes and I have been working on some things already, and I’m always looking for new artists to flesh out my concepts. I’ll probably be stepping away from the mainstream routine, not concern myself with the commercial aspects of the music business or the critics in the principal cities, but play universities and smaller cities. Though one thing I hope to do is go into the Public Theater in New York, take over one of the small theaters on a cyclical, regular basis, bring in African drama, movies, music, dance—performing arts. I’ve been talking to George Wolfe [the Public’s producer] about it.

“I’ve run into so many great artists from Africa and Brazil during my travels,” he says. “You know, we’re a cultural monolith, the U.S., dominating the world market—which wouldn’t necessarily be so bad, if we weren’t so mediocre.” By which Belafonte seems to mean unfocused, unanchored, small-minded, complacent and pointless.

These are the qualities Belafonte rails against and seeks to root out of himself even during interviews, charging himself with a musical mission. “I have to make a change,” he says, “change up the rhythms of my performing troupe, go after a more internationally rhythmic sound. I love the music of South Africa—and a song like ‘The Wave,’ which has music that’s filled with metaphor. ‘Paradise in Gazankulu’ is another song I’ve been doing that depicts the South African experience—about the price and pain of getting so-called paradise. Right now is the most crucial time in the history of South Africa, so the nation’s youth must understand it’s a long and painful journey, an agonizing process to grow out of the morass created by the past. In ‘The Wave,'” he quotes, “‘We are the flow, we are the wind/and soon the rock must go.’ As the sea washes against the rock—so we should not surrender or capitulate about our ideals, but rather be tenacious and consistent about our goals.

“I reject the concept of ‘purity,'” Belafonte continues. “Early in my career what annoyed me was not that I was considered inauthentic, but that I was being called so by others who didn’t know anything of the authenticity of which they spoke. First of all, I was singing original songs that took off from calypso, but certainly weren’t meant to be calypso. I didn’t want to be, or claim to be, a calypso singer—there were others who did that, and I didn’t want to take anything away from them. I took heart from what Brownie McGhee said: that all songs are original, if they’re your own expression. I think a lot of that criticism came from people who were disgruntled that they didn’t get over.

“I wanted to do something original, of my own. After all, the beboppers weren’t pure jazz players, in the eyes of the dixieland players. I was back then and hope I remain wide open to other music and other musicians, but I won’t be governed by other musicians’ limitations—no, I’m too busy trying to purge myself of my own. I look for musicians with skills of craft, people who are able to play, who exercise command over their instruments, who can accent the music with different moods and sounds.

“We take time with the music. When we first met, I worked with Richard Bona

“I’m going on with a percussionist and bass player and drummer, guitarist, an African thumb piano and a kora player. That’s a remarkable instrument, the kora. It’s a harp, guitar and piano all rolled up into exotic string sound—and just the basic playing technique dictates certain accents to the music. Bona plays both bass and guitar, and he helps shape up the rhythms. The rhythms—that’s what’s key to bringing, or perhaps retaining, the African interpretation of the music, and making the English language accommodate it.

“That’s a big problem,” says Belafonte, who’s arguably conquered it, though some make think he’s compromised with it, “translating the ingredient of language. The answer, I believe, lies in the physical way we sing. We’re constantly looking for ways to re-define address and speech, through our music.”

Then it’s about the delivery of material?

“I look for repertoire that takes me to my limits, which I try to go beyond, and gives me something to communicate to my audience, which is the real test. I don’t coddle or condescend to my audiences, nor do I permit the audience to intimidate me. I remain always alert to the difference between musical and vocal syntax—and because of that, I’m convinced music must accommodate the text.

“In a performance, it’s incumbent that the audience understands you. If it doesn’t—who cares? Is it that you don’t want to work? No, the worst part of that kind of lapse of communication is that the art doesn’t fulfill itself.

“So we arrange the music for communication and metaphor, then I ask myself, have we cheapened the integrity of intent, or enhanced it? The most important thing to me about ‘The Banana Boat Song’ is that before America heard it, Americans had no notion of the rich culture of the Caribbean. Very few of them did, anyway, which made no sense to me. It made no sense to me back then that people in America would not respond to the Caribbean culture I knew in joyous, positive ways. But there were these cultural assumptions then about people from the Caribbean—that they were all rum drinking, sex-crazed and lazy—not that they were tillers of the land, harvesters of bananas for the lordly types who owned the lands.

“I thought, let me sing to offer a new definition of these people. Let me sing a classic work song, about a man who works all night for a sum equal to the cost of a dram of beer, a man who works all night because it’s cooler then than during the day. Robeson said ‘When you get them to sing your song, you’re making the first step towards inviting thoughts that might be uplifting and instructive.’ I’ve kept that advice in mind when I’ve walked in front of black American audiences who might be suffering from anti-semitic myths and sung ‘Havah Nagilah.’ You’d be surprised, most of them tend to assume this is an Arabic song, and they love it. I’ve enjoyed singing it, also, in Germany, where the echoes of 50 years ago ring on.

“The history of U.S. popular song? Well, I don’t have much resonance with Stephen Foster, say, as much as I understand where he came from, and respect that for his times he was a poet who grasped that pop sense of the period. Now, the spirituals and the work songs from which Foster drew his inspiration, to me those are the much richer lode to be mined. And I believe America was the worse off for the fact that that wealth of African-America culture was ignored, or denigrated, until blues and jazz finally commanded the attention of the other [white] America. To me, it’s a marvel we should have emerged with such rich cultural contributions despite all that pain inflicted on the people who created them.

“And what’s equally amazing,” Belafonte picks up enthusiasm, “is the extent to which white youth in America, especially today, is influenced by black kids from the inner city, by their body language, their black English, their taste in clothes. You know my production Beat Street [a movie about hip-hop]? I saw hip hop culture then as a dynamic, important expression of people who couldn’t find cadence with the other America. These people created their own inner dynamic and treated the mainstream society as wholly irrelevant—and that society reached out, pulled it in, consumed it, corrupted it.

“Well, nothing in America remains incorruptible,” Belafonte grumbles, “not since the moral center of this country has become so lost. Today we’re caught in a struggle against our immoral appetites, whereas it used to be that you could judge the American moral sense by how it played into some noble causes—as recently as when Dr. King put the example of true morality before the nation, saying we need our civil rights, it’s unfair to withhold them from us, we can’t live with that.

“Now, as long as we are committed to profit as the central dynamic of our existence, we’re in crisis. It’s the bottom line theory, in terms of commerce. Look at tv: nothing comes across that invention that’s worthy of listening to, pertaining to the power, purity and dynamics of the arts, due to the system in which it exists. Or take another example: One sees in Japan the support of enthusiastic audiences for jazz unlike anything here. I well remember the clubs of the ’50s”—as well he should: Belafonte was backed up on his first opening night at the Royal Roost by Al Haig and volunteer sitters-in Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Tommy Potter and Max Roach. At the Renaissance awards he hailed Roach as “my link to the past and the future.”

“Back then America was enjoying the height of its jazz expression. And it’s not that jazz doesn’t make money. It’s that it doesn’t make enough money.

“Oh, I’m sanguine,” Belafonte’s tone shifts. “I look at each individual, and at the beauty and power of art, and I don’t think great art will die.” He’s even more than sanguine, leaping back into the pop music fray.

“I was ready to go deep into the motion picture world, to write a book, to find a play to do, when [Island Records’] Chris Blackwell wrote to obtain video rights to the PBS show. He also asked me, ‘Why aren’t you recording?’ Was it that nothing interested me. I replied, ‘Because I can’t overcome the industry’s obstacles to making the music happen.’ And Blackwell wrote back, ‘What if that changes?’ Well, I could be resurrected myself, but I’m not half so interested in doing that as in introducing new musics to the new generation of listeners who’ve grown up around us. And that’s how my label has come about. I’m going to put out music unencumbered by bottom line attitudes, music that’s not to be judged by accountants, and that might put a smile on America’s face. I’m looking for concepts and pollination, and I expect to get something out on Niger by mid ’98.

“My label will be independent, distributed by Island. Niger is named after the river, of course, but a lot of people will want to know where the other ‘g’ is. I’m glad to get that word out so it will be on the tongue—that in itself will provoke debate. The river Niger runs through the countries from which most of the peoples of the African diaspora come—a label name helps identify a label’s mission, and that’s part of mine, to explore music from those cultures. I’d like to go to the Georgia Sea Islands, too, which blend that culture with life in the new world, and find some of the plentiful black American music that still addresses aspects of that age-old tradition. It persists generation after generation, because there are young people in our culture who want to do things the way the masters did.

“Am I proud I’ve contributed to or been linked to crossover?” Belafonte considers a direct question. “I’m ambivalent. I like it that I’m welcomed in the places I go because of the popularity of some of my work, but then I also want to get past that image of what I do, get it out of the way. I’ve survived throughout my career, and to me it’s been magical.

“I’ve gone against the grain and I’ve come up roses. I’ve been involved with the greatest struggles of our time, the fight for our civil rights in the U.S, and the fight to free South Africa, which I was able to bring attention to in the U.S. by bringing out great South African artists, Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba and the others. Over my life, I’m pleased to find that the moral point of view in all these cases prevailed. My anxiety about them was, at first, quite intense, but now look: Nelson Mandela is the icon of the 20th century, and Dr. King has a national holiday in his honor. Everyone, today, is into world beat music. I had a privileged place in the process. The rewards have been substantial, make no mistake.

“Some people,” he considers, “ask me, ‘What about the sacrifice?’ The sacrifice! The ones who say this are the guys sitting around their Beverly Hills swinging pools, studio people at their parties. I say, ‘Sacrifice!’ Wait a minute—did you ever meet Dr. King, have him at your home for dinner, walk and talk with him? Did you ever know Fannie Lou Hammer or Paul Robeson or Bobby Kennedy? Did you go to Africa?

“I’ve sacrificed nothing,” Harry Belafonte concludes, calm yet steely with conviction. “I say to such people, ‘I simply wonder what it is you’ve lost.”

* * *

Belafonte’s label Niger Records does not seem to have gotten off the ground. I haven’t read My Song, but have seen Sing Your Song, and learned more from it, especially about the Civil Rights era. On the Colbert show, Belafonte says he still sings “occasionally,” before the host lures him into lifting a now gravelly voice with still impeccable phrasing.

I watch for Belafonte’s movies to be programmed, especially Odds Against Tomorrow, The Angel Levine (with Zero Mostel),

“I just had a great lust for life and lust for what was going on in America,” Harry Belafonte tells Colbert, in answer to why he’s at the center of so much significant activity over the past 60 years. “I felt I had a responsibility to reach into that misfortune and make a difference.” Good thing he did.

howardmandel.com

Subscribe by Email |

Subscribe by RSS |

Follow on Twitter

All JBJ posts |