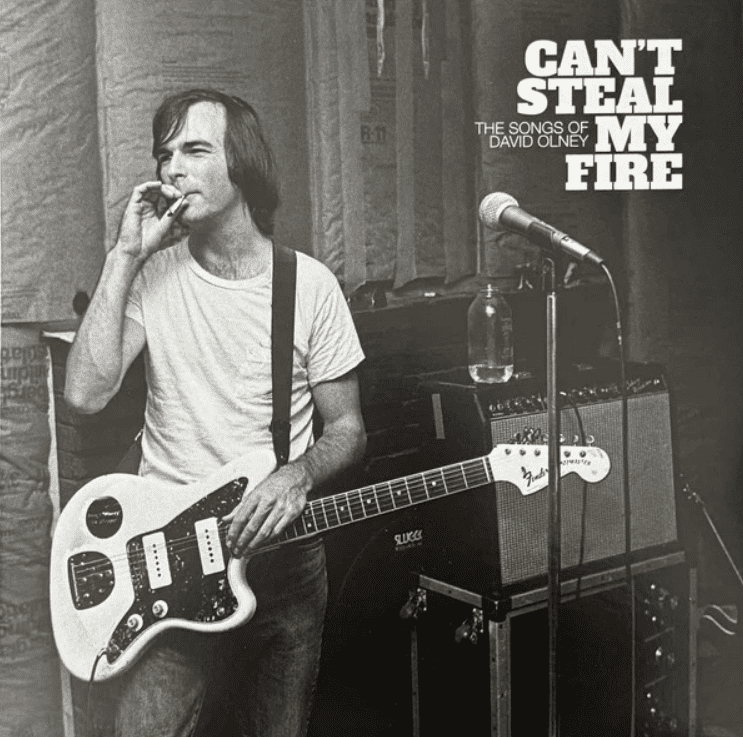

FOUNDERS KEEPERS: Can’t Steal My Fire: The Songs of David Olney

Near the bottom of my stack of indifferently folded black t-shirts rests a relic from 2003, a wry marker from the career of the late Nashville singer-songwriter David Olney. “David Olney’s World Tour of Nashville,” the back reads, listing six performances over six days. Those Music City shows, that t-shirt, some radio promotion and the usual good press notices were pretty much all the noise his eleventh (of twenty) solo studio releases made.

Fame was not to be his curse. But his gifts as a songwriter were so blindingly evident that a dozen labels, give or take, chose to make them heard.

David Olney died on stage in Florida, on January 18, 2020, in the middle of his third song. He apologized — those were his last words.

Four years in the making, Can’t Steal My Fire: The Songs of David Olney (New West), includes contributions from hall-of-fame Americana (whatever that is) artists including Steve Earle, Lucinda Williams, and Dave Alvin — and the first new recording from Willis Alan Ramsey since 1972. Executive producer Gwil Owen, a formidable songwriter in his own right (and frequent Olney co-writer), has done a superb job honoring the power and majesty of these seventeen songs.

Olney wrote with the gruff spirituality of Jon Dee Graham, the poetic clarity of Kevin Gordon, and the relentless musical curiosity of Doug Sahm. (If none of them are quite household names either, well…) Consider, for example, Mary Gauthier’s reading of “1917,” an anti-war song written from the perspective of a Paris prostitute — a chancy thing for a man of any age to try. Olney has given us an elegant tale, unfolding slowly and gently, and Gauthier caresses his words with profound compassion, her phrasing reminiscent of late period Marianne Faithfull. Or try Buddy Miller’s wonderful spinning of the grifter’s tale, “Jerusalem Tomorrow,” a kind of back masked sermon filled with an almost-believer’s doubts.

Emmylou Harris recast “Deeper Well” for Wrecking Ball, making it Olney’s best-known track. Lucinda Williams opens the album with a slow, weary, almost plaintive take that hews closer to the songwriter’s original. If “Sister Angelina” wasn’t written for Steve Earle, it should have been. He captures the essence of the thing — another unfolding story about a desert drifter saved, physically, by a nun — without even a hint of bravado.

But the banger comes courtesy of the McCrary Sisters. “Voices on the Water” (one of two Gwil Owen co-writes) cannot be played too loudly. Olney found power in the stories of the Bible, if not, quite, succor there. The McCrarys, daughters of the late Sam McCrary of the Fairfield Four, sing with no such doubts. In an album filled with songs of questing uncertainty, the soaring joy of this song reaches further.

The balance is a tasteful wonder. On “Steal My Thunder,” Dave Alvin recreates the terse magic of Olney’s rock band, the X-Rays (who appeared on “Austin City Limits” in 1982). “Women Across the River” is a remarkably tender track from Willis Alan Ramsey, the legendary Texas songwriter who last released a single, self-titled album in 1972 (the origins of “Muskrat Love”). “But the women across the river/Never learned to build the wall” lands differently, today; Ramsey inhabits those lyrics with weary wisdom and grace. Knoxville legend R.B. Morris, who once cut a brief swath across Nashville and recorded for John Prine’s label (Oh Boy Records) offers up “Always the Stranger.” And Janis Ian unearthed a song she co-wrote with Olney titled “She’s Alone Tonight.” The double album finishes with a live version of “Illegal Cargo” from Olney’s friend and patron, Townes Van Zandt.

Illusions of success be damned, this is the stuff that counts.