THE READING ROOM: Going Off the Rails with Whiskeytown

Thomas O’Keefe tells a great story, and he has plenty of them to share with us in his bumptious, roaring, swooping roller-coaster-ride account of his years with the enfant terrible of alt-country, Ryan Adams. O’Keefe, now the tour manager for Weezer, was the tour manager for Whiskeytown from 1997 until the band broke up in 2000.

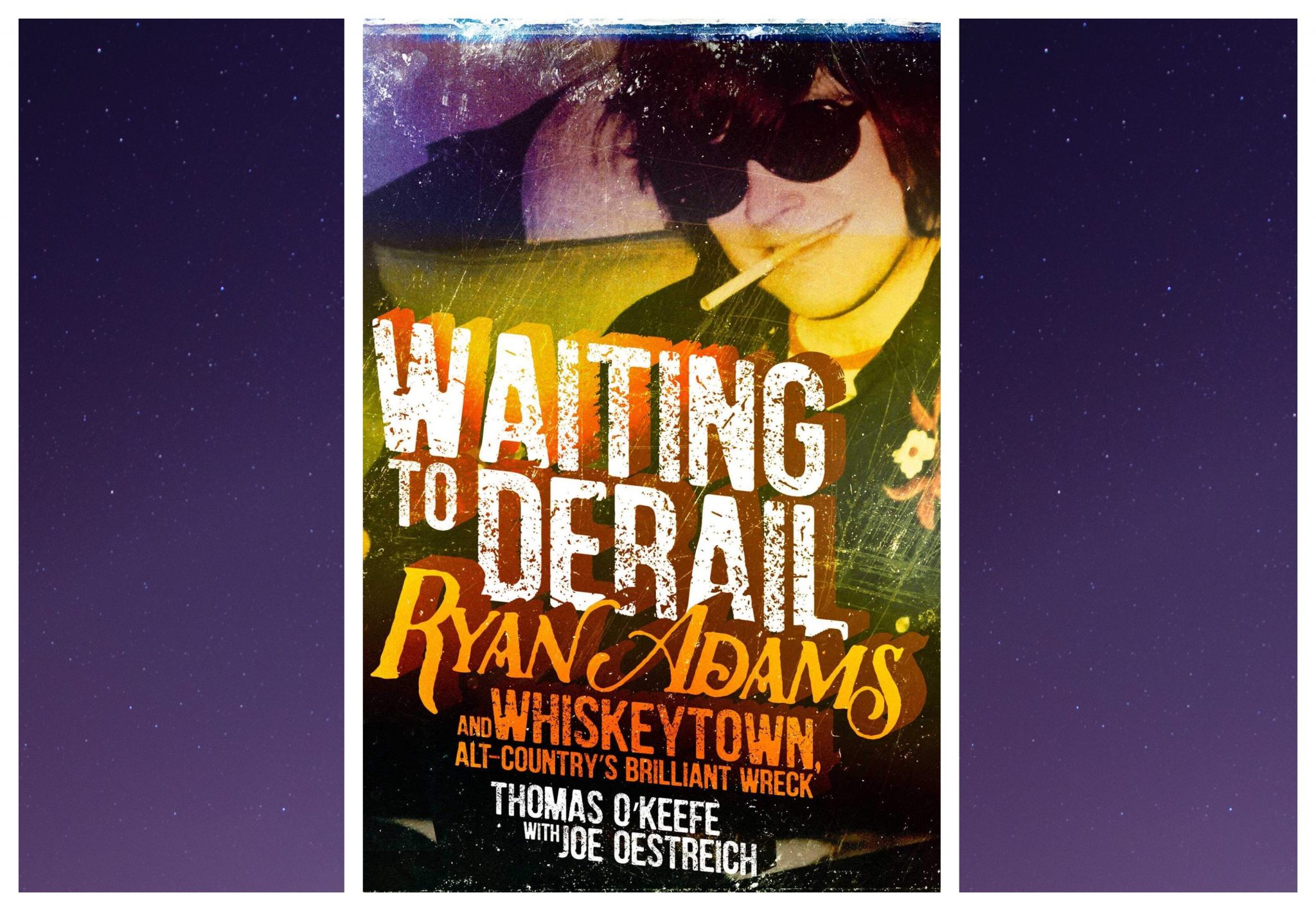

A punk rocker himself — O’Keefe played bass in ANTiSEEN — he was accustomed to the excesses of the touring life, so when Adams’ management, Jacknife, called him and asked him to be the tour manager for one of their bands, Whiskeytown, fronted by Adams, he accepted the job. Waiting to Derail: Ryan Adams and Whiskeytown, Alt-Country’s Brilliant Wreck is O’Keefe’s tale of the three years he spent getting “Ryan and the band to the shows and through the shows, all in the name of helping him live up to his talent and to the major-label break he’d been given. I was the conductor, charged with keeping Whiskeytown on the tracks.” As O’Keefe discovers, of course, working with Adams could be like herding a snake, and the tour manager spent as much time — maybe more — talking Adams out of tight spots or drunken lethargy or tantrums as he spent admiring Adams’ songwriting genius.

Before he became tour manager, O’Keefe had never met Adams, though he’d seen him around, mostly at 7 Even, a convenience store near North Carolina State University in Raleigh, where Whiskeytown got it start. “Standing in front of the coolers, lit up by the overhead fluorescence, Ryan looked like a South-of-the-Mason-Dixon Paul Westerberg — all mussed-up hair and wrinkled clothes. With his big black glasses, he also looked like Austin Powers, and by then a few local musicians had started knocking on Ryan by referring to him as Mike Myers’s character.”

Whiskeytown’s album Strangers Almanac came out in July 1997, and the band set out to tour behind it with O’Keefe doing his best to keep the band on track. “Tour-managing Whiskeytown,” he writes, “was going to be like chaperoning eighth graders in a class trip to DC. Eighth graders who drank and smoked pot.” Prior to their first show in Carbondale, Illinois, O’Keefe had watched the band’s “half-assed practices,” but he’d never seen them do a “full-tilt show” until that night. At that show, he discovered Caitlin Cary’s inestimable role in the band: “Ryan might have been the heart of Whiskeytown, but Caitlin Cary was the soul; the melancholy sound of her fiddle, the way her vocal harmonies floated above Ryan’s, adding a teaspoon of sugar to the salt-and-snot of Ryan’s voice … there was no replacing Caitlin.” In fact, O’Keefe comes up with formulas to explain the musical dimensions of the band: “Ryan + Caitlin = The Musical Beauty of Whiskeytown; Ryan + Phil [guitarist Phil Wandscher] = The Punk Rock Spirit of Whiskeytown.” While Wandscher and Adams often taunted each other and Wandscher left the band (Adams fired the entire band except for Cary), Cary remained with the band until its end in 2000.

The thread that ties together O’Keefe’s book is Adams’ unpredictability. The singer could storm off the stage in the middle of a set if he disliked the tone of the crowd, or he’d simply refuse to play a gig because he didn’t like the place, and sometimes he’d be so drunk he’d sleep past the lobby call. The band’s taping at Austin City Limits offers one example of Adams’ unpredictability — and the challenges that O’Keefe faced as tour manager: “As we drove away from the Austin City Limits taping that day, I knew that at twenty-three, Ryan was already a good artist. He could copy better than anybody I’d ever met. And I suspected he was ultimately, like Picasso, not just a copyist but a thief. A great one. Still I worried he’d shoot himself in the foot long before his own artistic vision would have a chance to blossom. As brilliant as the ACL set was, to me it was just as bittersweet as the sound of Caitlin’s fiddle. Because it confirmed what I had begun to suspect: in order for Ryan and Whiskeytown to be world-beaters, all Ryan had to do was give a shit. Unfortunately, on lots of nights that was too much to ask.”

Yet, Adams’ brilliance, as O’Keefe illustrates, lies in his songwriting process. “The songs were already floating in the atmosphere, and he detected them before everybody else. Tunes got beamed down into his head one after another. His job was to jot down the lyrics and internalize the melodies as soon as they hit him. His job was to catch the lightning … I was learning what got Ryan most excited: bringing a song into the world. The instant the inspiration hit him — that was the absolute best moment for Ryan.”

Toward the end of 1998, Whiskeytown played the Fillmore in San Francisco and Adams followed his self-destructive bent down to the bone. Just as O’Keefe was patting himself on the back for not resigning from the band earlier in the day because he recognized Adams is a “one-in-a-million songwriter,” Adams launched into “Piss on Your Fucking Grave,” the last song of the night. It was a “full-blast punk rock song that has exactly zero to do with alt-country … He kept rocking. Singing sweetly but with venom. Fuck you, fuck you, fuck you. In those words, I heard: Fuck you, Bill Graham. Fuck you, Fillmore. Fuck off, rock-and-roll sacred ground … He was pissing on the grave of No Depression magazine. Pissing on the grave of Outpost Records. Pissing on the grave of the whole damn music business. Saying fuck you to the idea that Ryan Adams was alt-country’s Kurt Cobain. Fuck you to everybody who had expectations and for who and what Ryan Adams was supposed to be. And fuck off to the Ryan Adams he’d created for himself.”

Filled with colorful stories, O’Keefe’s book tells a sprawling tale of excess and excellence. Waiting to Derail sometimes grows tiresome because Adams’ antics grow tiresome, and the book suffers from the same problems that other books like this one suffer from: two or three stories of a rising star’s exploits might be funny, but an entire book of them causes our eyes to glaze over. Despite this, O’Keefe knows how to reclaim our attention when it starts to wander, and he knows how to shift the plot of the story enough to keep it interesting when it starts to grow stale. At the same time, this is a book for the fans of that brief moment in time when Whiskeytown and Adams were alt-country darlings. O’Keefe had a ringside seat to those years, and Waiting to Derail invites us to sit beside him as he watches the roller coaster eventually go off the rails.