Bill C. Malone opens his 2010 book Country Music, U.S.A., stating that country music “defies precise definition, and no term (not even ‘country’) has ever successfully encapsulated its essence” (Malone 2010, 1). In the past century, the ‘country music’ genre has comprised several different sub-genres, including hillbilly, old-time, bluegrass, the Nashville Sound and the rivaling Bakersfield Sound, Western swing, countrypolitan, outlaw, Texas country, Red Dirt country, neotraditional, pop country, ‘bro country’, and many more in between. However, in the last 25 years, country music has become more and more synonymous with the emerging pop and bro country sub-genres, gradually diluting the older, more traditional sounds. All the while, many musicians are regularly faced with difficult career decisions as the music industry mold cyclically changes.

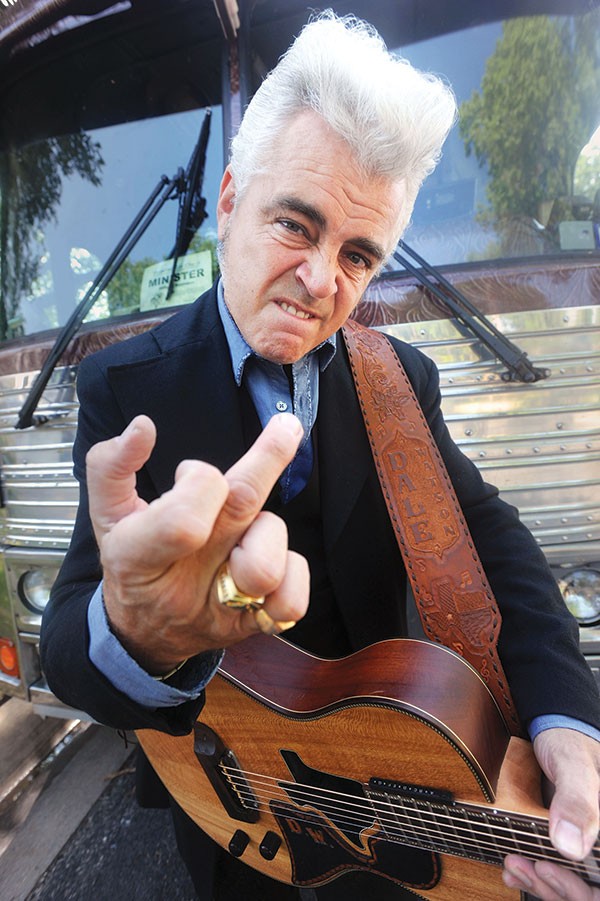

The driving forces behind what music we hear on the radio or in concerts are for the most part, the record labels themselves. The music business is a business after all and what sells the most will decide what kind of music and what artists receive the most airplay and attention. In the 1960s and 1970s, country music went through an identity change with the development of the Nashville sound, a more polished sound for those with a refined palate so to speak. The Nashville sound, which featured orchestral strings, less twang and more crooning, was the brainchild of RCA president, Chet Atkins, who later regretted its creation. “Of course, I had a lot to do with changing country, and I apologize. We did it to broaden the appeal and to keep making our records different, to surprise the public” (Windeler 1974). Another reason for the changes in country music’s sounds over the years were to better market the music to younger audiences and attract new, youthful fan bases. Moreover, as the music continues to change and the artists get younger and less authentic so to speak, some artists have had to adapt to the ways of new Nashville. Others refuse to bend to fit this mold. One man who refused to contort into this mold is Alabama-born singer and Texas music legend, Dale Watson.

“COUNTRY MUSIC’S GOTTEN SO DILUTED. THAT’S A GOOD WAY TO PUT IT. IT STARTED OUT WITH JIMMIE RODGERS AND HANK WILLIAMS BEING 100 PROOF. AND NOW, HERE WE ARE WITH JASON ALDEAN AND BIG AND RICH. WE’RE LIKE DIET DR. PEPPER. WE GOT NO ALCOHOL IN IT.”

Dale Watson grew up in a family surrounded by country music. His father was a country music fan and performer in his own right, along with his brothers who also played. Watson followed suit, writing his first songs when he was 8 or 9 years old and performing his first paying gig at 14. Watson’s pursuit of music soon found him in Pasadena, Texas, performing with his first band, The Classic Country Band. Later, following the advice of Tex-Mex rockabilly artist Rosie Flores, Watson landed in Los Angeles for a few years before working as songwriter for a publishing company in Nashville, Tennessee around 1991-92. “When I first started out and I was looking for a record deal...they liked what I did, they said: ‘Okay, we love what you do. Now change’…At that time…drinkin' songs were a big no-no. And…they had a sound they wanted to hear…so it was all about bending to…fit what the record company wanted” (Watson Interview).

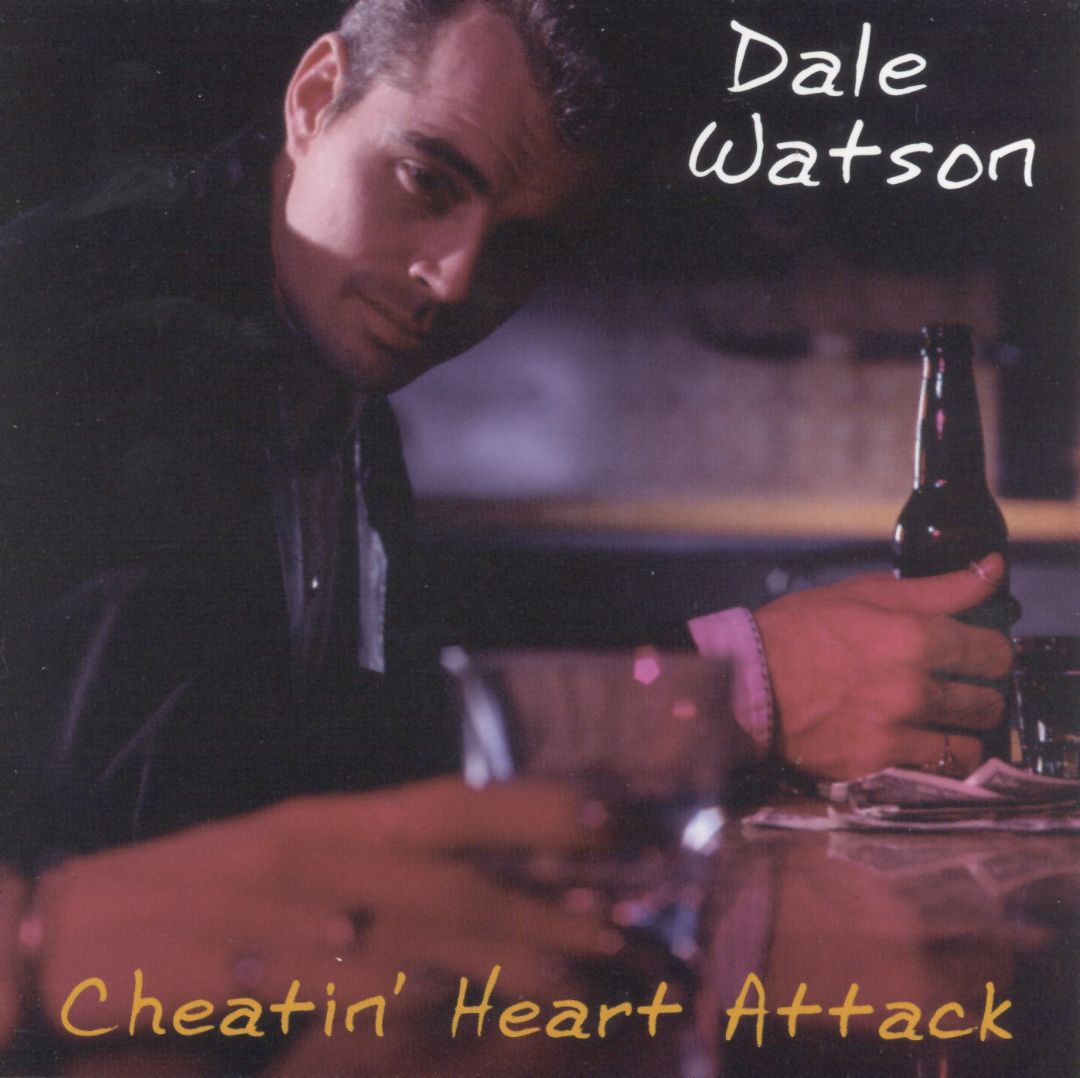

However, with the rise of pop country music in the late 1980s and early 1990s, concurrent with the emergent careers of singers such as Garth Brooks and Shania Twain, country music perpetually hung many staunch, traditional country music artists, such as Watson, out to dry. As a matter of fact, in the early 1990s, country superstar Johnny Cash was a “free agent” so to speak, as he was not signed to any record label in Nashville. Watson, upset by this, penned the song “Nashville Rash,” written in the style of a complaint letter to Merle Haggard. The song, from Watson’s 1995 album Cheatin’ Heart Attack, is the epitome of the state of traditional country music during the rise of pop country music styles. Watson sings:

"Help me Merle, I'm breakin' out in a Nashville rash

It's a-looking like I'm fallin' in the cracks

I'm too country now for country, just like Johnny Cash

Help me Merle, I'm breakin' out in a Nashville rash /

Shoulda' known it when they closed the Opry down

Things are bound to change in that town

You can't grow when you rip the roots out of the ground

Looks like that Nashville rash is getting' 'round” (Watson 1995).

Nudie suits, AM radio stations, crying pedal steel guitars, moaning vocals, and sepia-toned lifestyles, often linked with our grandparent’s music, were now a thing of the distant past. The industry deserted their long-time, loyal audiences in a lucrative attempt to attract a younger, hipper generation. “Anybody can write the shit they’re writing in Nashville” Watson proclaimed (Watson Interview). Watson left Nashville after 10 months in search of greener pastures. He found those pastures in Austin, Texas, where he has spent the past two and a half decades of his life, enjoying the honky tonk and beer joint circuits, playing traditional country music and doing things his way.

In 2013, Platinum-selling country music star and current host of NBC’s The Voice, Blake Shelton, provoked outrage among traditional country music fans and artists during an interview with GAC while taping a Backstory segment. Shelton controversially remarked:

“If I am ‘Male Vocalist of the Year’ that must mean that I’m one of those people now that gets to decide if it moves forward and if it moves on. Country music has to evolve in order to survive. Nobody wants to listen to their grandpa’s music. And I don’t care how many of these old farts around Nashville going, ‘My God, that ain’t country!’ Well that’s because you don’t buy records anymore, jackass. The kids do, and they don’t want to buy the music you were buying” (Coroneos 2013).

Kyle “Trigger” Coroneos, author of the popular country music blog, Saving Country Music, wrote extensively about this controversy and the validity of Shelton’s claims. According to Coroneos, Larry Rosin, President of Edison Research said at a Country Radio Seminar in Nashville in 2012:

“I believe that we as an industry have really made a mistake in our conception of our own stations. While many people don’t want to listen to classic country music, some still do, and we’ve let them float away…We run the risk that we just are more and more pleasing to fewer and fewer people until all we are is ecstatically pleasing a tiny, unsustainable number of people” (Coroneos 2013).

As a result of Shelton’s outburst, many country artists came out of the woodworks to express their displeasure, most notably legendary country artist Ray Price, who said:

“Every now and then some young artist will record a rock and roll type song, have a hit first time out with kids only. This is why you see stars come with a few hits only and then just fade away believing they are God’s answer to the world. This guy sounds like in his own mind that his head is so large no hat ever made will fit him. Stupidity Reigns Supreme!!!!!!!” (The Boot 2013).

Shelton would later apologize to Price, who passed away nine months after the heated exchange of comments. Fellow Grand Ole Opry member Jean Shepard, who passed away in 2016, shared similar sentiments: “I guess that makes me an old fart. I love country music. I won’t tell you his name, but his initials are BS, and he’s full of it!” (Burchard 2015). Dale Watson, also offended by Shelton’s disparaging comments, spearheaded a virtually nationwide sonic movement, ultimately crucial to the preservation of traditional country music.

Watson created the “country” music genre conglomerate called Ameripolitan shortly thereafter in 2013. According to the Ameripolitan website, “This thought-provoking word is intended to be an invitation to discuss the future of the music that is important to so many of us. By leaving the hopelessly compromised word ‘country’ behind and exclusively using the term ‘Ameripolitan’, our intention is to reestablish this music’s own unique identity, elevate its significance and help reinvigorate it creatively” (Ameripolitan Music Awards). Watson and I spoke at length about his decision to name this new movement Ameripolitan. “I didn’t have the name for it so if I’m gonna be out here—I’m gonna jump on my own island and do what I do—to call myself country isn’t correct. It misleads anybody who’s a fan of mine and it misleads people who are country fans…I wanted something that when people heard it, they didn’t already have a preconceived notion” (Watson Interview).

“GENTRIFICATION. THAT’S WHAT HAPPENED IN COUNTRY MUSIC.”

Because of the vast complexities of defining exactly what country music is and what it is not, and the shift from roots and tradition towards pop music and dollar signs, Watson had troubles deciding on an appropriate name that would effectively supplement his motives. “When you…are in an old neighborhood and then they start coming in knocking down all the beer joints that you liked and the old mom and pop stores that you grew up with and tearing down the old houses so they can build a condo…That’s what they did with country music and…that ain’t why I got into it. So it’s just changed so much that it’s not what it was. It’s not the same. It isn’t the country music I knew and now…country music—it is country music because…the industry…decides what is country music and they decided they want the big condos and the gentrified night clubs or whatever you wanna call them. You know, everything is high dollar and hipster and— so I’d rather just…take what was in my neighborhood and I moved down the road. That’s what usually happens…but I can’t call it [Ameripolitan] country because they are country” (Watson Interview).

In Richard Peterson’s 1999 book, Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity, Peterson analyze six definitions of the word ‘authenticity’: Authenticated, not Pretense; Original, not Fake; Relic, not Changed; Authentic Reproduction, not Kitsch; Credible in Current Context; and Real, not Imitative (Peterson 1999). Watson said many people wanted him to call the genre ‘real country,’ or ‘classic country,’ but he feared this might pigeon-hole him into a “retro type of thing where people just write you off as something that’s already been done.” He continued, “Anytime you use a root word, you have to form your—your own definition based on the root. And that root word is country and to me, the word country nowadays doesn’t have any roots whatsoever, so it made no sense to use the word ‘country’ in the description” (Watson Interview).”

Looking at Ameripolitan music from the outside in, it may seem as though one is watching through a portal into the past. Ameripolitan artists such as Dale Watson, Pokey Lafarge, Celine Lee and Rosie Flores and many more often don slick pompadour hairstyles, western and Nudie suits and long, frilled dresses, complete with shimmering rhinestones and extravagant colors. Yet, rather than being totally written off as ‘kitsch’ or ‘imitative’ of Hank Williams, Johnny Cash or female rockabilly legend, Wanda Jackson, the artists within Ameripolitan embrace the styles of and traditions of their musical heroes, acknowledging the immeasurable impact each one had on the music. The Ameripolitan movement is offering these modern-day artists a chance to reach wider, unbiased audiences, and even introduce those audiences to the influential artists of the past, ensuring the roots are never forgotten.

According to lead singer and acoustic guitar player Jason Boland of the red dirt country group Jason Boland & the Stragglers, the 2016 recipient of the Ameripolitan Award for Best Outlaw Group: “I’ve always thought it was important to keep one foot in tradition and the other pointed in the direction you want to go. I didn’t invent the G chord, so I’m standing on the shoulders of the giants that did, and on the shoulders of some great songwriters that have come before me. I’m using an old stencil, but adding my own colors” (NEWS). Boland continues, “We pay homage, but we don't want to copy or be a throwback act. All you can do is try to take the music that inspires you and take it further. And make it personal” (BAND). Just because it is 2017 and our televisions are no longer black and white, it is still possible to produce real, traditional-sounding country music, derivative of country music’s roots, featuring original songs about real people. Ameripolitan artists are doing just that, albeit without the support or recognition of Nashville.

The Ameripolitan movement harbors artists ranging from four main genre subcategories of country music: Honky Tonk, Western Swing, Rockabilly, and Outlaw, though artists may participate and be classified as part of multiple categories. Originally, Watson intended to host a one-time award show to showcase traditional artists of these four categories and to “let people know that are out there doing it, ‘hey, keep doing what you’re doing, because people do like it. And you do have an audience and don’t listen to that asshole [Blake Shelton].’ That’s what he is–he’s an asshole.” Now in its fifth year of existence, the Ameripolitan Awards show has grown from the Wyndham Garden Hotel in Austin, Texas, to the Paramount and Stateside Theatres in Austin, to the Guest House at Graceland in Memphis, Tennessee in February of 2018. Watson says he owes Blake Shelton, however for letting him prove a point to the music industry:

“What he did was he said what Nashville thinks…he just kind of pulled off the Emperor's clothes, you know what I mean? He said ‘yea, that's the way we think—we don't—we think everybody who likes that kind of music are old farts or jackasses. We don't care what you think.’ And so, that's why I started—I did the award show--thinking it would only be one, I never thought it'd be more than one time. And—it sold out—It's sold out every time” (Watson Interview).

The increasing popularity of Ameripolitan music does raise some thought-provoking questions though. As the awards show continues to gain traction and more artists begin to join the movement, how much of an impact, if any, will it have on mainstream country music, country radio, and the industry in general? What sort of boundaries exist in country music that separates the essence of Ameripolian music from its popular mainstream counterpart? Malone’s aforementioned quote about the difficulties in defining country music, “the commercial exploitation of southern folk music” (Malone 2010 p.34), as a genre relies heavily on the audience’s perceptions of what country music is. In Keith Negus’ 1999 book, Music Genres and Corporate Cultures, he discusses the research of Richard Peterson and Roger Kern. Peterson examines the genre by distinguishing between two types of country music performers: hard-core and soft-shell. Hard-core performers, such as Hank Williams, personified the South and stereotypical ‘hillbilly’ characteristics in terms of dialect, songwriting, fashion, and lifestyle. Contrarily, with soft-shell performers, such as country crooners Jim Reeves and Ray Price, “the accent was on Sonorous, polished, and dignified interpretations of songs rather than on a hard-edged outpouring of raw emotion” (Peterson 1999, p. 140). Likewise, the rough and rowdy lifestyles were not so much a part of the success or legacy of these performers. According to Watson, “Country music’s gotten so diluted. That’s a good way to put it. It started out with Jimmie Rodgers and Hank Williams [Hard-Core] being 100 proof. And now, here we are with Jason Aldean and Big and Rich [Soft-Shell]. We’re like Diet Dr. Pepper. We got no alcohol in it” (Watson Interview). Negus continues to explain Peterson and Kern’s research, suggesting that:

“…the production of country hinges on the connection between fan and performer and that, in my terms, a broader genre culture is crucial for maintaining the meanings of country styles…In terms of the industry, the performer’s songs, lyrics, visual identities and stage manner are produced and mediated through distinct ‘systems of production’, marketing outlets and promotional systems” (Negus 1999).

Additionally, Negus argues that while the audience’s ‘outsider’ perspective tends to hold the industry accountable for the progression of any specific genre, the audience themselves are just as responsible for the “standardization and routinization” of said genres through country music radio, “one of the most obvious forces…” (Negus 1999).

In closing, it is important to consider what the future holds in store for Ameripolitan music. More importantly, we must question why any of this matters to the future country music. In my opinion, the future of Ameripolitan music, and country music in general is largely based upon its past. It can be argued that the Ameripolitan genre was crafted from the roots of the music from places all across the globe: Ulster to Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta to Bakersfield, California, and Austin, Texas to Nashville, Tennessee. Country music owes a great deal to its roots, to establishments such as the Grand Ole Opry, and to hard-core and soft-shell performers, such as Hank Williams, Hank Thompson, and Jim Reeves, or Jim Ed Brown. Shelton’s comments exposed how the music industry in Nashville truly feels about old, jackass musicians and their affinitive devotion to their “grandpa’s music,” but, Watson and his peers do not expect every new country artist on the scene to sound exactly like Merle Haggard, or Kitty Wells, or Faron Young. Rather, their mission in continuing to develop Ameripolitan is to preserve the legacies of these legendary musicians and their respective sounds. Jewish theologian David Novak once said, “Roots can live without branches, although truncated; branches cannot live without roots” (Novak 1991). Watson persistently preaches and acknowledges the importance of the country music industry holding on to these roots because it is the past which will help truly develop the future of country music

By: Jimmy Fitch

Works Cited

Ameripolitan Music Awards, www.ameripolitan.com/copy-of-home.

“BAND.” Jason Boland & The Stragglers Band - Band, www.thestragglers.com/index.php?pg=band.

The Boot Staff. “Blake Shelton, Ray Price Debate Over 'Old Fart' Country Music.” The Boot, 25 Jan. 2013, theboot.com/blake-shelton-ray-price/.

Burchard, Jeremy. “Country Maverick Jean Shepard Has Harsh Words for Modern Country.” Wide Open Country, 9 Nov. 2015, www.wideopencountry.com/jean-shepard-has-harsh-words-for-modern-country/.

Cooper, Peter. “Veteran 'Opry' Members Fuming Over Changes.” The Tennessean, 29 Sept. 2002.

Coroneos, Kyle "Trigger". “Blake Shelton Calls Classic Country Fans ‘Old Farts’ & ‘Jackasses.’” Saving Country Music, 23 Jan. 2013, www.savingcountrymusic.com/blake-shelton-calls-classic-country-fans-old-farts-jackasses/.

Dale Watson. “Nashville Rash.” Cheatin’ Heart Attack, HighTone Records, 1995.

Kern, Roger; Peterson, R. A. (1995) Briefings: Hard-Core and Soft-Shell Country Fans. In: The Journal of Country Music, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 3-6. Available at https://openmusiclibrary.org/article/565091/.

Negus, Keith. Music Genres and Corporate Cultures. New York: Routledge, 1999.

“NEWS.” Jason Boland & The Stragglers Band - News, www.thestragglers.com/?pg=news-detail&newsid=68.

Malone, Bill C., and Jocelyn R. Neal. Country Music, U.S.A. University of Texas Press, 2010.

Novak, David. “Judaism, Zionism, Messianism: Telling Them Apart | David Novak.” First Things, 1 Feb. 1991, www.firstthings.com/article/1991/02/judaism-zionism-messianism-telling-them-apart.

Windeler, Robert. “Chet Atkins Helped Country Music Move Uptown-and Now He Regrets It.” PEOPLE.com, 16 Dec. 1974, people.com/archive/chet-atkins-helped-country-music-move-uptown-and-now-he-regrets-it-vol-2-no-25/.

Comments ()