Hambone: an ingredient for delicious soup, or an instrument for scorn, or for strong rhythm, or for hot sex?

In 2009, the Richmond professional baseball team was looking for a new franchise and was about to move to a new home place in Virginia. On this occasion, it wanted to replace its name “The Defenders”. One of the six names on the short list was “The Hambones”. This alternative was dropped when the Virginia state division of the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, an African-American civil rights organization, spoke out against it, calling it offensive. It said the hambone referred to a dance that slaves had been forced to perform to entertain whites. Its Executive Director stated: “hambone was done on the plantation by African captives and was used at minstrel shows to entertain white audience.” He added: “The fact that it [Hambones] is being considered for use is unacceptable, unfathomable and unconscionable.”

The baseball team apologized immediately that it was “unaware of any negative, derogatory, or offensive connotations to the name and that the organization in no way intended to offend any individual or segment of society with its inclusion in the name of the team contest”. In a press release the team explained that the possible name was chosen from different submissions it had received, and its sole intent was to utilize the concept of Virginia Ham and its history in the region. The team finally opted to associate itself with flying squirrels rather than with hambones.

Clearly, there is thus more to a ‘hambone’ than the bone in ham meat. Join me in the cut off the meat of the bone to try to discover what is behind it. This requires going back in time.

I start in the Spring of 1974. The first issue of a magazine was published that was dedicated to African American literary artists. The magazine, that upon its second issue in 1982, renamed as “Hambone has been qualified as “an indispensable little magazine” that for more than a quarter-century featured the work of major African American poets. According to its editor, Nathaniel Mackey, who also gave the magazine its name, “Hambone” carries African references and resonance, alluding to the rhyme with the same name. Contrary to what the Richmond NAACP would contend a few decades later, its name was thus not seen as an offensive label by the African American literary society.

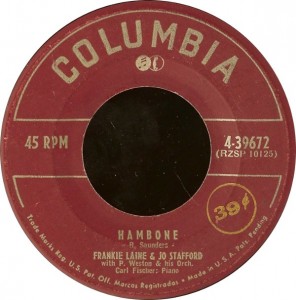

Let us go a bit further back in time. Frankie Laine, aka Mr Rhythm, a successful American singer, songwriter, and actor whose career spanned 75 years, from his first concerts in 1930 to his final performance in 2005, hit Billboard again in 1952 with a song called “Hambone”, sung with Jo Stafford, considered one of the most versatile vocalists of the era. The song was one of Laine’s many top 10 hits (Columbia n° 39672, shellac 10″), and its lyrics went as follows:

“Hambone, hambone

Where you been?

Round the world and I’m going again

What you gonna do when you come back?

Take a little walk by the railroad trackHambone, hambone

Where’s your wife

Out to the kitchen, cooking out rice

HamboneHambone, hambone

Have you heard?

Papa’s gonna buy me a mocking bird

If that mocking bird don’t sing

Papa’s gonna buy me a diamond ring

If that diamond ring don’t shine

Papa’s gonna take it to the five and dime

HamboneHambone, hambone

Trying to eat

Ketchup on his elbow, pickle on his feet

Bread in the basket

Chicken in the stew

Supper on the fire for me and youLook at him holler, look at him moan

That hambone just can’t hambone

Hambone (…)”

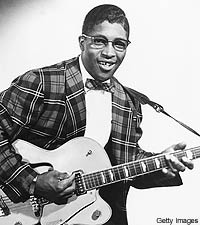

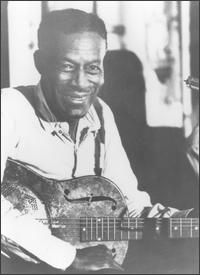

The “Hambone” dance and rhythm would, however, be made popular worldwide disguised as the “Bo Diddley beat”, introduced by a fantastic musician born in Mississippi by the name of Ellas Otha Bates, who, under his stage name Bo Diddley, would conquer the hit charts. The “Diddley beat” is a rumba-like beat inspired by a style also displayed by street performers who played out the beat by slapping and patting their arms, legs, chest, and cheeks while chanting rhymes like Dee Clark’s “Hambone Kids”. The “Bo Diddley” drum beat was an immediate hit and inspired in later years many other variations in songs like “Not Fade Away” by Buddy Holly and by the Rolling Stones, “Willie & the Hand Jive” by Johnny Otis Show and by Eric Clapton, “Magic Bus” by The Who, and “Desire” by U2 (Marcus, et. al). These were only the most famous; the ”hambone” song has been performed by numerous others (Kirby Stone Four, The Bell Sisters, Orgone, The Black Diamonds,….).

The Hambone rhyme and beat was clearly in the air. Michael Hawkeye Herman (°), today one of America’s finest acoustic guitarists and blues educators, wrote me some time ago that when he was growing up it was common for folks to participate in hambone at social gatherings and parties and sing a song that goes: “Hambone, hambone, where you been? Around the world and back again”. Meanwhile folks kept and played rhythm with hand claps and body claps and added improvised verses to the song. It corresponds to what Derique McGee, an African American entertainer and circus artist and teacher, who today keeps the art of “hamboning” very much alive, reminisces when he says he learned the act as a child in Berkeley. McGee calls it a “living bit of history, a neglected part of our heritage” (J. Isenhour).

The hambone dance had already a long history behind it. C.L. Keyes describes the hambone as a dance derived from the antebellum dance called the “juba” (°°), performed to rhyming verses by the patting and clapping of one’s thighs, chests, hands, and even the top of the head (°°°). It goes back to the very roots of black music (W. Erbsen). C.M. Phillips traces its origin to a game played in Congo by young girls, called ‘nsunsa’, that involved crossing the hands underneath and above the thighs. The thigh-and-chest slapping dance imparted confidence and self-spirit. In Brazil it would evolve as the ‘bate coxa’ (meaning literally ‘slap thigh’); in America the game was translated as hambone. The hands are struck, or slapped, and the fingers are snapped in ways that create beat and rhythm in various ways to show the performer’s dexterity in creating percussive rhythms. The ‘hambone’ is a close relative to the ‘tap dance’ that would be popularized in northern entertainment in the 1840′s by the black stage dancer William Henry Lane, billed as master Juba, one of the greatest dancers of the antebellum period (Malone & Stricklin). Some authors (Conyers) see the pedigree extend even as far as the urban Charleston which became hugely popular in the 1920′s.

The game dimension of the ‘hambone’ is highlighted also in the ‘Encyclopedia of African music’, edited by Emmett G. Price, one of America’s leading experts on African American Music and Culture. Price stresses the vocal elements of the African American game songs that include repetition of short phrases, the use of nonlexical phrases and the call-and-response structure, which on their turn can be linked to the African ‘ring dance’ and ‘shout’. White & White observe that the hambone was used to introduce the young people into the complex rhythmic patterns needed for the creation of music and dance, a role which it has continued to serve until quite recently. They stress that this function furthermore teaches independence. C.K. Keyes adds that the male grownup teenagers performed the hambone as a courtship game when they rhymed: “Hambone, Hambone, ham in the shoulder / Gimme a pretty woman and I’ll show you how to hold her”.

The central role of drum and percussion in the African (American) culture is essential to the musical understanding of the hambone.

During the first Atlantic slave trade of the 1500′s to the South American colonies of Portugal and Spain, it was already noticed that drumming was an important aspect of the gatherings and spiritual ceremonies for the West African slaves (A. Wilson). Drums were played with the hands or with sticks. Additionally, they used it to beat out messages to one another, including warnings about the arrival of a plantation owner. In their culture, the drum and its percussive corollaries were a powerful instrument in the political and cultural unification of their group and were as such a corner stone of their social life (W.R. Scott & W.G. Shade). The communication capacity of drums is also stressed in E. Nielsen’s study of folk dancing when she notices that drums could reproduce some West African dialects.

It is common to find in the literature on hambone as a dance that it developed or gained importance when the plantation owners started to realize the potential subversive dimension of drums. The plantation owners realized that the drum not only was a means to communicate but was also connected to armed conflict and had been used in African culture to call men to the battle field. Whites gradually understood that the drum could be seen as a focal point of physical and cultural resistance. The disconcerting drum sound became, for the white, a source of anxiety and fear as it could spread the language of insurgency (S. Gikandi).

Drums were progressively banned by European Americans during the 18th century, which is a curious observation since the African Americans were allowed to continue to play the drums in the militia bands (their style was, however, European inspired and approved). Drumming was, for instance, banned in South Carolina in the aftermath of the Stono Rebellion of 1739 – the largest slave uprising in the British mainland colonies before the American Revolution (S. Gikandi). A similar prohibitive, legal reaction took place in Virginia, and other states copied their legislation on the South Carolina and Virigina model (M. Knowles). The South Carolina Slave Act itself incorporated many of the terms of earlier slave acts of the West Indies, including thebanning of “wooden swords, and other mischievous and dangerous weapons, or using or keeping of drums, horns, or other loud instruments, which may call together, or give sign or notice to one another of their wicked designs or purposes” (quoted in D. Epstein).

I believe the literature makes too strong an association between the banning of drums and the popularity of hambone, almost as if banning the drum was a condition for the popularity of the hambone. It is too simplistic when, for instance, W. Erbsen states that “slaves substituted their own bodies for the outlawed drums and the results were called “Patting Juba” or Hambone”.

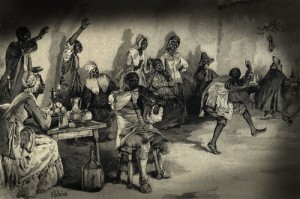

I see a few arguments to support my view. In the first place, as I already mentioned above, hambone had its roots in Africa. Moreover, it was not only drums which were the target of prohibitive legislation; also dancing itself was associated with a sense of deviance. African dances were seen as covers for organized resistance and could function as an alibi for outlawed assembly (S. Gikandi). Much like the drum, dancing could contain messages that were at first glance invisible to the white eye. For instance, in Argentina public dances by slaves, known as the “candombes”, were banned three times in the last half of the 18th century. In Brazil, the “candomblé” (dance of slaves), was banned at the beginning of the 18th century. Also, in the antebellum American South the dancing of slaves was kept a careful eye upon by the white authorities. V. Sheperd draws our attention to the slave owner’s fear towards slave dances which were regarded as ‘liberated bodies in action.’ Dancing as a recreational institution attracted the attention of the legislators because it could act as a metaphor for spiritual and eventually physical independence (Sheperd, 227). The dancing could not be totally suppressed and the Roman Catholic religion of the white in the Deep South colonies manifested greater tolerance to it than the Upper South Protestant ethics. R.D. Abrahams describes in a lively way the dancing performed by the slaves during the corn shucking feasts, but these were organized by the plantation owner himself and were very functional for his own benefit. If the dancing did not take place in a white controlled context, it was considered as ‘heathens’, ‘barbaric’ and potentially dangerous.

Furthermore, hambone was only one of the many dancing styles that were performed by the African Americans and which were at the core of their culture. Rhythm was a natural aspect to their way of life and their labor activities. Moreover, dancing was a temporary release from the soul crushing burdens of bondage, and hambone was not the sole dance to fulfill this function. Dancing could take shape in all kind of social gatherings (J.M. Coggeshall). It was enough that “a bunch of people would be sitting around..and somebody’d say: “I’ll bet you I can beat you buckin’.” The “buck dance”, “flat footing”, “hoedown”, “jigging”, “sure footing”, and “stepping” are some of the traditional (Appalachian solo) dances. The “rubber leg”, the “camel walk”, the “frog dance” and “rabbit dance”, “pitchin’ hay”, “cuttin’ wheat”, “pony’s prance”, “the swan’s bend”, “the kangoroo” or “shooting the chute” are just a few other speaking names of dance styles that were popular (S. Floyd). The “cakewalk” (°°°°), another example, that was popularized by the black face minstrelsy, is said to find its origin in the dances performed by the African slaves when they mocked the fancy dance styles and ways of walking of their white owner. The inner rhythms of the African slaves and population found their expression in many dance styles of which the hambone was just one.

The hambone had of course the major advantage of being at disposal any moment as accompaniment to singing. Even when no instrument was readily available, the human body could function as a means of creating rhythm to the singing and dancing. This aspect made it attractive, and each plantation of some size had at least one slave who could ‘pat the juba’ (White and White).

The emphasis placed on the popularity of the hambone in light of the banning of the drums, which supposedly pushed the slaves to use their own body as drumming instrument, further obscures the overall creativity that African Americans displayed in all aspects of their daily life, work and entertainment. There was no end to their inventiveness and improvisation in the struggle of survival, and this revealed itself in many talents, which very often found their inspiration in their African cultural background. Miller and Smith sketch how slave carpenters produced all the cooperage that was needed on the plantation, as well as many wooden objects today produced in plastic or metal. The woodworking skills were deployed for making for instance bowls, buckets, washtubs, spoons and boats. They improvised from materials that were at hand. Seats were fashioned of corn shucks. A tree branch was cleverly transformed into a rake or pitchfork. Gourds were remodeled into birdhouses. The talent in handwork prevailed also during leisure time and was expressed when carving images that had a spiritual meaning, or when creating children’s toys. Slave canes, for example, were often decorated with snakes, alligators or other animals, carved out with a great sense for detail. Let us also bring to mind the talent that was displayed by the women in creating quilts.

The same creativity and inventiveness was applied to fashion musical instruments, used when they were allowed time to themselves at Saturday nights and Sundays, and for their social gatherings. This amazing dexterity speaks for itself in the words of Wash Wilson, born a slave in Louisiana when he describes the types of musical instruments used at slave dances (K. Hazzard-Gordon):

“Us take pieces of sheep’s rib or cow’s jaw or a piece of iron, with a old kettle, or a hollow gourd and some horsehair to make de drum. Sometimes dey’d get a piece of tree trunk and hollow it out and stretch a goat’s or sheep’s skin over it for de drum. () Dey’d take de buffalo horn and scrape it out to make de flute. () Then dey’d take a mule’s jaw bone and rattle de sticks ‘cross its teeth. Then day’d take a barrel, and stretch a ox’s hide cross one end and a man sat ‘stride de barrel, and beat on dat hide with he hands and he feet and iffen he get to feelin’ de music in his bones, he’d beat on dat barrel with his head. ‘Nother man beat on wooden sides with sticks.”

The slaves using their own body as musical instrument was thus fully in line and coherent with the genius they not only showed in crafting all kind of objects for use in the daily life and for work, but also with fashioning a wide range of other musical tools from all kinds of materials available to them. It was a perpetuation of their traditions as skilled artisans and music makers and performers. As I said: there was no end to their creativity.

“Hambone, hambone

Where you been?

Round the world and I’m going again

What you gonna do when you come back?”

The hambone represents heritage, lessons and triumphs: a high symbol for survival through creativity. Bennet and Dickerson call it a metaphor for black cultural experience, and as a matter of fact for the experience of all oppressed and poor people who possess the faith to receive the scraps of the world and are able to make a feast out of it. This takes vision. C.J. Larue: “There was no end to the utility of the neck bones. Through the common experience of suffering, in the depth of oppression and slavery, emerged a faith and generosity that was the source of life, joy, creativity, nourishment, community, and blessing” (p. 54).

But this historical journey into the rhyme and dance does not help us to fully grasp why the Virginia NAACP objected against the use of ‘hambone’ as a possible name for the renewed Richmond Pro baseball team. There has to be more at stake.

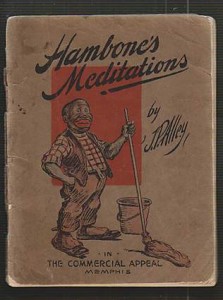

“Hambone’s Meditations”, which continued to be published until 1968, would only later be unambiguously criticized for its racist character. In the wake of the 1968 strike in Memphis hospitals, schools, and the federal housing authority bodies, and its growth into a major civil rights struggle, attracting the attention of the national news media, the Hambone caricature was suppressed from the ‘Commercial Appeal’. Let me mention that Martin Luther King went to Memphis to support the striking employees. It was during this strike that, on April 3rd, King delivered his final speech “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop”. Keith Miller, when discussing the famous speech, highlights that Martin Luther King made it clear to its audience that Memphis newspapers, as for instance the “Commercial Appeal”, were definitely more racist than they appeared at first sight. Earlier in his speech, King had reminded his auditors of “Hambone”, when he dismissed African American subservience, of the kind epitomized in “Hambone”, as utterly outdated (Miller). A day later, King was assassinated.

As well as referring to a dance and rhyme with roots in African culture, “hambone” has thus historically a racial connotation. In American slang, it is still anything but flattering when one calls an African American a ‘hambone’, meaning he is clownish. Besides, there is still another reason we might think of why the NAACP advised against the Richmond baseball team to use “Hambone” as the name for its new team. In Southern vernacular, hambone is associated with the act of having sexual intercourse and/or with the genitals (Stephen Calt). The word surfaced in this meaning in several early blues songs which, generally spoken, frequently used the ‘hokum’ as a technique originating from the black face minstrelsy and that used analogies or euphemistic terms to make sexual insinuations. Flipping through the pages on early blues, I found the sexual allusion popping up in at least four songs.

In “I never knew what the blues were” (OK 8151, 72479-B, April 1924), the blues and jazz singer Virginia Listan, with the piano accompaniment of Clarence Williams, expresses her desire to get sexual satisfaction when she sings: “I ain’t got nobody but I’m gonna get my hambone boiled, oh daddy / I’m gonna take it down home, ’cause these Northern men will let it spoil.” (Calt). A similar appetite is revealed in the 1925 “Southern Woman’s Blues” by Ida Cox, who wants to go back to the sunny South “where (she) can get (her) hambone boiled, because these northern men are about to let (her) poor hambone spoil”. (Debra DeSalvo).

Blues men tapped the same beer. Ed Bell, sometimes placed on the same level of blues monuments as Charley Patton, but with a more modest discography, recorded in 1927 “Hambone Blues”, as B-side to the magical “Mamlish Blues” (Paramount 12524). While he turned his back to secular music later in his life, that year he was unambiguous when he shared with us his strong feeling that he “got to move to Cincinnati, (to) get (his) hambone boiled, (since) women in Alabama gon’t let (his) hambone spoil.”

Note that it was not uncommon for the early blues singers to incorporate food terminology in their music as metaphors to reflect sexual needs and acts (J.T. Edge). Both men and women blues singers used food items in their lyrics to make the topic of sex more socially acceptable. The songs substituted for parts of the human anatomy terms as banana, pig meat, jellyroll, jelly bean, and pie. A biscuit roller evoked the image of an attractive young woman with desirable sexual skills. Coffee grinding had the connotation, as did boiling the hambone, of sexual intercourse. Blues presented sexual desire in an ingenious way, reducing it however at the same time to a simple organic or mechanical act (Robert Springer).

With the above various meanings of ‘hambone’ in mind, ranging from a culinary ingredient, over a strong rhythmic dance and a degrading nickname to an imaginative reference to sex, we would understand why naming the Richmond baseball team as ‘Hambones’ would have provoked chuckling with some, and feelings of indignation with others. “Flying Squirrels” was after all not that bad as a final choice.

_____________________________________________________________

FOOTNOTES

_____________________________________________________________

(°) My sincere thanks go to Michael who has suggested me to explore the hambone topic. I owe him a lot for this proposal, and for his continuing stimulation of the exploration of the blues’ roots. Naturally, I am solely accountable for the content of my writings.

(°°) One theory says that “Juba” comes from the word “nzuba”, a thigh-slapping dance of Kongo origin. The name derived from the Ki-Kongo verb “zuba” that means “to slap”. African descendants performed the Juba in Haïti and in Cuba, where it was called “Giouba” and “Djouba”. (quoted in: F.W. Evans, Congo Square, 2011)

(°°°) If you have difficulty visualizing the act, have a look first at the footage that I collected for you at the following links:

http://j.mp/SteveHickmanHambone

(°°°°) Allow me a small step aside on the cake walk. The naming of this dance is a bit of a puzzle (R.D. Abrahams). One theory says that the name comes from the cake given as a prize for the couple during slave feasts who danced best. It has been quoted in the same context as the chalk line dance during which slaves were to dance and walk on a chalk line on the ground with a pail of water on their heads. The cakewalk is interpreted frequently as a kind of signifying dance that made fun of the high manners of the white folks. As one author concludes the Cakewalk was meant “to satirize the competing culture of supposedly ‘superior’ whites. Slaveholders were able to dismiss its threat in their own minds by considering it as a simple performance which existed for their own pleasure” (B. Baldwin, 1981: The Cakewalk: A study in stereotype and reality. Journal of Social History, 15 (2), 205-218.)

___________________________

SOURCES

_________________________

http://www.wtvr.com/news/wtvr-hambone-dropped,0,1040506.story

http://www.worldartswest.org/main/discipline.asp?i=44

http://www.nytimes.com/1987/07/18/arts/re-creating-hambone-body-music-of-the-past.html

http://funkystuffblog.com/funkystuffblog/tag/black-memorabilia/

http://msgw.org/slaves/hunley-xslave.htm

http://www.wric.com/Global/story.asp?S=11304578

http://www.discogs.com/Frankie-Laine-Jo-Stafford-Hambone-Lets-Have-A-Party/release/1858647

http://www.bodiddley.com/index.cfm/pk/content/pid/400026

http://drumsdatabase.com/bodiddley.htm

http://www.nationalcigarmuseum.com/Themes/Racist.html

http://www.memphishistory.com/Politics/Newspapers/JPAlley.aspx

http://www.comicconnect.com/bookDetail.php?id=366212

http://funkystuffblog.com/funkystuffblog/tag/hambones-meditations/

http://www.memphishistory.com/Politics/Newspapers/JPAlley.aspx

http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=hambone

Books :

– Keith D. Miller, Martin Luther King’s Biblical Epic: His final, Great Speech, 1998

– William M. Tuttle, Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919, 1996

– Joseph B. Atkins, Covering for the bossess: labor and the Southern press, 2011

– Stephen Calt, Barrelhouse words: a blues dialect dictionary, 2009

– John T. Edge, Editor, The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, 2007

– Robert Springer, Fonctions sociales du blues, 1999

– Debra DeSalvo, The language of the blues from Alcorub to Zuzu, 2006

– Rose M. Nolen, Hoecakes, Hambone, and All That Jazz: African American Traditions in Missouri, 2003

– Nathaniel Mackey, Paracritical Hinge: Essays, Talks, Notes, Interviews, 2005

– Cheryl Lynette Keyes, Rap Music and Street Consciousness (Music in American Life), 2004

– Wayne Erbsen, Front Porch Songs, Jokes & Stories: 48 Great Sing-Along Favorites, 2001

– John M. Coggeshall, Carolina Piedmont Country, 1996

– Ming Fang He, JoAnn Phillion, Personal, Passionate, participatory inquiry into social justice in education, 2008

– Greil Marcus et al., Rockabilly: The Twang heard ’round the world: the illustrated history, 2011

– Michael Bennet, Vanessa D. Dickeron, Recovering the black female body: self-representations by African American women, 2000

– Clarenda M. Phillips, African American fraternities and sororities: the legacy and the vision, 2010

– Jack Isenhour, He Stopped Loving Her Today: George Jones, Billy Sherrill, and the Pretty-Much Totally True Story of the Making of the Greatest Country Record of All Time (American Made Music), 2011

– Cleophus J. Larue, More power in the pulpit, 2002

– Jennifer A. Lemak, Southern Life, northern city: the history of Albany’s Rapp Road Community, 2008

– Sherman E. Pyatt, Alan Johns, A dictionary and catalog of African American folklife of the South, 1999

– Shane White, Graham J. White, Stylin’: African American expressive culture from its beginnings to the zoot, 1999

– Emmett George Price, Encyclopedia of African American music, vol. 3, 2010

– Samual A. Floyd, The power of black music: interpreting its history from Africa to the United States, 1996

– John Lowe, Jump at the sun: Zora Neale Hurston’s cosmic comedy, 1994

– Amber Wilson, Jamaica the Culture, 2003

– William Randolph Scott, William G. Shade, Upon these shores: themes in the African-American experience, 1600 to the present, 1999

– Simon Gikandi, Slavery and the culture of taste, 2011

– David Buisseret and Steven G. Reinhardt, Creolization in the Americas, 2000

– Dena J. Epstein, Sinful tunes and Spirituals, 2003

– Roger D. Abrahams, Singing the master, 1992

– Erica Nielsen, Folk Dancing, 2011

– Verene Shepherd, Working Slavery, pricing freedom: perspectives from the Caribbean, Africa and the African Diaspora, 2011

– Mark Knowles, Tap Roots: the early history of tap dancing, 2002

– Jack Shuler, Calling out liberty: the Stono slave rebellion and the universal struggle for human rights, 2011

– James Walvin, Black ivory: slavery in the British empire, 2001

– Langston Hughes, Essays on Art, Race, Politics, and World Affairs, 2002

– Shane White, Graham J. White, The sounds of slavery, 2006

– Randall M. Miller, John David Smith, Dictionary of Afro-American Slavery, 1997

– Charles Joyner, Down by the riverside: A South Carolina Slave Community, 1986

– Katrina Hazzard-Gordon, Jookin’: the rise of social dance formations in African-American culture, 1992

– Bill C. Malone, David Stricklin, Southern music/American music, 2003

– Wilma King, Stolen childhood: slave youth in Nineteenth-century America, 1998

– James L. Conyers, African American jazz and rap, 2000