Happy Birthday, “Like A Rolling Stone”

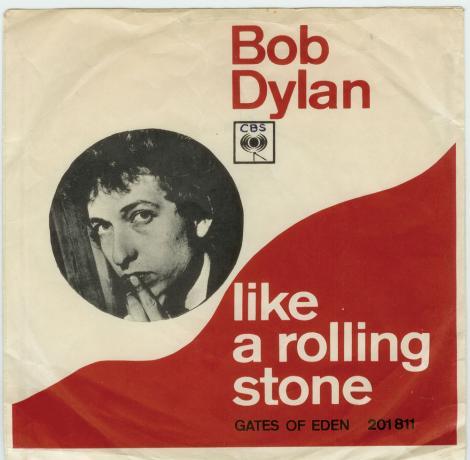

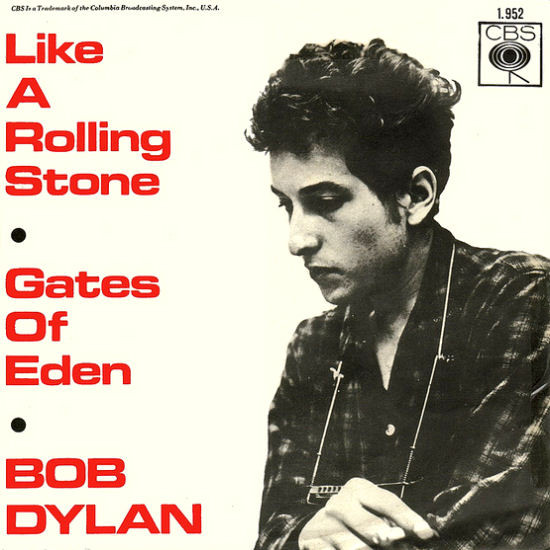

On July 20, 1965, Columbia Records released the single “Like A Rolling Stone,” backed with “Gates of Eden.” Bob Dylan, who had recently turned 24, was in the middle of the most creative period any musician I can think of has ever had. His releases that year of Bringing It All Back Home in March, and Highway 61 Revisited in August — followed hard by Blonde On Blonde in May 1966, all while on a crazy touring schedule, are still hard to believe. Heck, Mozart took five years for Le nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni and Così fan tutte.

Highway 61 Revisited, the album which “Like A Rolling Stone” sledgehammers as the first track on side one, was recorded in mid-June and in early August, 1965, at Columbia’s studios in New York. Dylan had just returned from his 1965 tour of England and a 24th-birthday vacation with Sara Lownds, and was preparing to go electric at Newport and keep in that vein on a year-ending tour with The Hawks (not yet The Band). His appearance at Newport fell between the two recording sessions for Highway 61 Revisited. The album was made in the way Dylan had begun to record by then. Musicians would assemble in a room. Dylan would take and re-take, compose lyrics and alter melodies, while the men waited, assisted, waited, improvised, re-took, recorded. (Men, I say, because Dylan’s bands, in studios and onstage, have been all-male, with the exception of a few guest performers and backup singers who generally did not play instruments on stage, for nearly fifty years.) Dylan did near-whole albums in one fell swoop. If a record didn’t sound right when it was finished, Dylan would, as he did during the Blonde On Blonde sessions in Nashville, and the Blood On The Tracks sessions in Minnesota, assemble another or a new group of musicians, and have at it again, working in the same intense manner until he was happy with the result. It’s a Sartrean way to record: lock the doors, put paper on the windows, and no one gets out of here alive until Bob says so. It’s also an immensely effective way to record, and one that has brought out unsurpassed performances on the songs by individual musicians like Robbie Robertson, Kenny Buttrey, Al Kooper, Garth Hudson, Charlie McCoy, Rick Danko, Larry Campbell, G.E. Smith, and Dylan himself. Some of the musicians, including Kooper and McCoy, have spoken years later about what it was like to be there, but no one has yet to say he wouldn’t have been there, if he could turn back time.

The star of those June sessions, produced by Tom Wilson, is what would become Dylan’s most famous song. Dylan is a constant reviser — and, when you hear those revisions in progress, you marvel. His work-in-progress on this song is wondrous to hear. Available for decades only in fragments, on bootlegs, they were released in November 2015 on the collector’s edition of The Bootleg Series Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965-1966. The many, many takes of “Like a Rolling Stone” show its remarkable evolution from folk to rock. The first take of this song is almost a folk ballad, quiet and gentle — Tom Wilson slates it as “CO86446, Like a Rolling Stone, One,” and with amazement you realize you’re listening to a waltz. Wilson even counts it out, like a dancing master: one-two-three, two-two three. Dylan’s presence is there in a plaintive, sweet harmonica, and his voice never comes in with a lyric, just the question, “It didn’t get lost?” and the take ends. The second begins with his voice, strong and barely accompanied with strumming strings, piano, and touches of harmonica and organ. Dylan begins his tale as tales all used to begin, with “Once upon a time.” The words, though, are still in progress. There’s no “complete unknown” — Dylan sings “sooooo unknown,” before stopping the take coughing, and insisting, “my voice is gone, man. Wanna try it again?” The song rolls out, slowly. “Be aware, doll,” not beware. “You used to make fun about everybody that was hangin’ out.” “To be out on your own, so unknown, like a rolling stone.” No “no direction home.” The take fades, and so does the folky sound, permanently.

Later, Wilson says gently, “Okay, Bob, we got everybody here, let’s do one, and then I’ll play it back to ya, and you can pick it apart.” The song now slated as “Like a Rolling Stone, Remake, Take One,” sounds like itself, from the clicky drum start and the clicky tack piano of Paul Griffin shared by Al Kooper’s rolling, billowing keyboards. The lyrics are more set — “when you’re on your own, without a home, like a complete unknown, like a rolling stone.” “Naw,” says Dylan at the end of the first refrain, “we just gotta work that part out.” They try again, but Bob has a false start, singing too softly. The only complete take kick-starts with the drum alone, organ and the rest of the band following. This is the version we know best: the Woodyesque, folky pronounciation — for instance, “stone” as “stawne” — the line “no direction home;” and, in the last refrain, the magnificent second of silence, after Bob’s first “how does it feel?,” between the crash of the drum and Kooper’s replying organ line. It fades into a jungly drumbeat and guitars turning plunky, being picked, it sounds like, as if they’re banjos.

Though this would be the album version, Dylan keeps on, with an edgier, snarkier version, slower; he punches out, and makes more nasal the “Now you don’ts,” almost speaking them as if he’s Rex Harrison, then stops abruptly. On the next take, Dylan has to laugh when he flubs a line, “threw the dumbs a dime, ha ha, let’s take it again.” The next time, they try it with a harmonica lead-in, and don’t go far with that. Wilson cuts off the next take because “there’s something wrong timewise.”

“Like a Rolling Stone” is a song of simile and questioning, but the questions are irrefragable, really. Dylan has always enjoyed being a riddler, leaving questions unanswered for you to grapple with. Here, the refrain asks directly, and repeatedly, how does it feel? The singer is challenging the “you” of the song, in this story of a princess turned pauper, Cinderella in reverse — if you take “Miss Lonely” to be the “you,” the “doll,” the “babe” addressed in all the verses. It all begins comfortingly enough with that kids’ bedtime story, folktale beginning of “once upon a time,” but veers quickly into the grim present. You haven’t got the freedom of a rolling stone, after all; you aren’t one, you’re only like one. Hangin’ out sounds pleasant, but how fast does it become the same thing as scrounging your next meal? Living on the street? The glamor of homelessness runs thin pretty fast; for every Huck Finn, freewheeling down the river, naked on a raft, there are thousands of bums and mystery tramps, ex-Napoleons exiled from past glories, starving well-educated failures. Freedom is the nothing that you’ve got to lose in this song, and a curse of it is that people still remember who you are. You aren’t a complete unknown — you’re like one, but the singer of the song knows who you are, and so do you. It’s a song in which you’re trapped, as the addressee and auditor, like an ant: there are many different ways to run, but without direction home or to any place in particular; you’ve lost your path, if you ever had it back at that once-upon-a-time beginning. Those who can help you survive you never respected, can’t trust. It feels as if they might do you harm.

Happy birthday to the greatest rock and roll song I’ve heard live in concert more than any other, and the one I’ll always love best.

*parts of this essay are from my longer writings on Highway 61 Revisited, published in Montague Street Journal (2010); and on The Cutting Edge (2015).