How Skippy White Built Boston’s Soul Scene

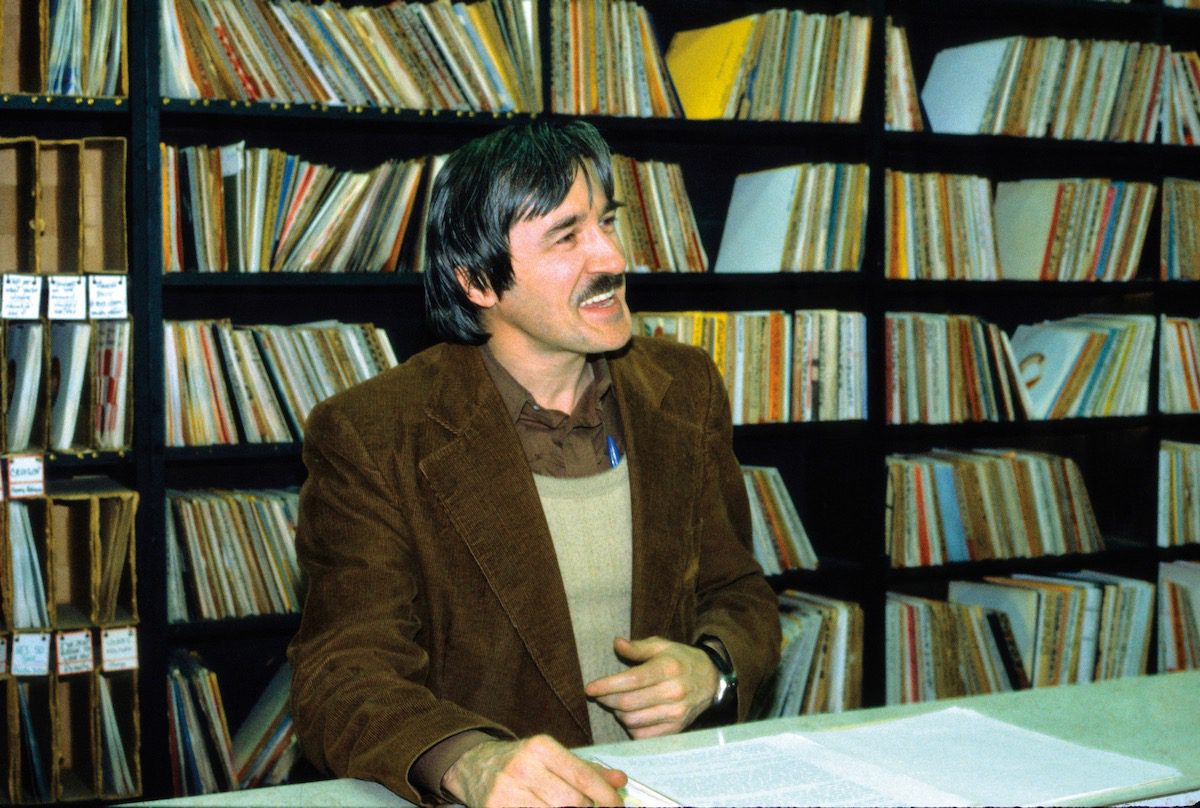

Skippy White in 1980 (photo by Ellen Nations, courtesy of Yep Roc Records)

As a radio personality, record store owner, concert promoter, and producer/manager of local artists, 86-year-old Skippy White has dedicated nearly his entire life to supporting soul, blues, and gospel music in Boston. He still remembers the moment that made it all happen.

“I was searching through the radio and I tuned into this program and heard a song I was familiar with,” says White. “It was 1953 and a DJ on Boston radio, Symphony Sid, and I happened upon him playing ‘Crying in the Chapel’ by The Orioles.

“Prior to my hearing this record, I wasn’t particularly enamored with what I heard on the radio — pop, country-western — I wasn’t crazy for it,” he adds. “But this blew me away and I was hooked on rhythm and blues from then on.”

Last October, Yep Roc Records released a compilation highlighting White’s passion for R&B and his work with gifted but relatively unknown Boston roots musicians. The 15-track album, The Skippy White Story: Boston Soul 1961–1967, is bolstered by comprehensive essays and liner notes penned by Boston musical luminaries and frequenters of White’s various shops and promoted concerts. Singer-songwriter Peter Wolf (of J. Geils Band fame), acclaimed author and music journalist Peter Guralnick, and Boston Globe reporter Noah Schaffer all contributed to those textual materials, but it was and soul singer Eli “Paperboy” Reed and his private collection of 45s and acetates that helped make the entire musical project possible.

Fred LeBlanc Goes WILD

Before he became Skippy White the radio personality and record store owner, he was Fred LeBlanc. Born in Waltham, Massachusetts, LeBlanc loved music since he was a teenager. After high school, he moved from the suburbs into Boston and began collecting records and purchasing in bulk.

From 1957 to 1960, he worked at the only place in Boston selling R&B, Smilin’ Jack’s College Music Shop. The store served as a primer for LeBlanc, allowing him to grow his collection and start his own side business as a distributor. Upon opening various boxes of 45s, he would take note of the companies that issued the records as well as those that packaged and shipped them. He decided to become his own middleman, reaching out and purchasing records wholesale at 15 cents apiece, which he would then trade or sell to stores (such as his employer) and consumers at a rate of 40 cents a copy, far below the 60 cents typically charged by wholesale outlets.

After World War II, many Black Southern migrants arrived in Boston and brought new musical sounds, tastes, and interests. LeBlanc became enamored with the Southern soul scene and saw how the Boston media market at the time was failing to provide that music to the area’s burgeoning audience. Inspiration struck, and he decided to reach out to radio stations about hosting his own late-night show featuring rhythm and blues music.

It was a hard sell. The first station he reached out to declined, opting to forego its 24-hour broadcast license and go off the air at night instead of running a show highlighting Black soul and gospel. Undaunted, he continued to seek a receptive station. He found a potential home for his idea with 1090 AM, WILD.

“One station that wasn’t doing well was WILD. It was playing Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, stuff I call ‘elevator music,’” LeBlanc recalls. “I had an interview with the owner, Nelson Noble, and the first question he asked I had to answer with a lie. He asked if I had experience on the air. If I answered in the negative, it would have been the end of the conversation; I had never been in front of a microphone before in my life, but I said, ‘Oh yeah.’

“Then he asked, ‘It’s not rock and roll, is it?’ I told him rhythm and blues and he said, ‘Get me four sponsors and I’ll give you a two-hour show,’” he notes. “They really needed the money.”

He picked up three sponsors right away: a local jazz club, a laundromat, and a variety store. LeBlanc thought Smilin’ Jack and his College Music Shop was a no-brainer for the fourth, as the radio show could help drum up business for the store. But his boss declined. With no other viable options, LeBlanc took matters into his own hands and became his own sponsor. “I decided right then and there with my meager funds to look for an empty store and found one for $50 a month.”

“I gave the landlady $50. She gave me a key, and one of my friends from Waltham helped me with the carpentry and setting up partitions,” he recalls. “I brought my records into the store from home, oldies that I bought wholesale, and opened Mass Records – The Home of the Blues.”

LeBlanc had his sponsors, a store, and a radio show. Now he needed a new name. His proposed DJ name of “Frantic Fred” was emphatically rejected, so he went with Fred White. After a well-known New York City personality named Fred Mack became WILD’s new drive-time DJ in 1961, White was encouraged to come up with a nickname and was dubbed “Skippy” by another WILD personality.

“I didn’t like it at first, but I couldn’t come up with anything, so that Saturday I went on the air as Fred ‘Skippy’ White,” he says. “The phone rang and everybody called me ‘Skippy.’ The next day, I dropped ‘Fred’ from then on.”

His name wasn’t the only thing to change. There was a disconnect for his listeners, who heard him reference his shop on-air and would call it expecting to hear his name and not “Mass Records – The Home of the Blues” when an employee answered. So White renamed it “Skippy White’s Mass Records — The Home of the Blues” and a community mainstay was born.

‘College of Musical Knowledge’

“Skippy, what you got?”

That’s what Peter Wolf would ask White every payday when he’d stop in to Mass Records. White, through his multiple stores — Mass Records and companion shop Big John’s Oldies But Goodies, which he opened in 1962 to meet the demand for the songs he was playing on his show — and WILD were crucial in the development of both Wolf’s personal tastes and Boston’s developing, yet vibrant, soul and blues scene.

“The radio station had really charismatic disc jockeys who played gospel, rhythm and blues, and blues. It was a great resource in Boston for people, musicians, and the urban community,” Wolf says. “Skippy was such an important voice. He would sell tickets to all the different shows — Otis Redding, Little Johnny Taylor, Bobby Blue Bland — and had amazing taste.

“His stores were a mecca for me, places where I bought many of the recordings I still own and treasure, and had so many personalities coming in and out of it,” he continues. “It was my college of musical knowledge.”

In the 1960s, White avidly read music magazines like Billboard and Cash Box and paid close attention to the breakout records in certain markets in the hopes of finding new music to play on his show. The approach paid off, and he specifically remembers being the first Boston-area DJ to play Ike and Tina Turner’s breakthrough 1961 single “Fool in Love” and Otis Redding’s 1964 hit “These Arms of Mine.” Naturally, copies of these singles could then be purchased at his various shops.

In addition to being places to buy the latest singles from Black R&B musicians, Skippy White’s stores became prime locations to learn about upcoming concerts at nearby Louie’s Lounge or Boston Arena, memorably great shows he was often involved in booking and promoting.

“He used to have these news sheets in his stores that would tell you when James Brown or other artists coming to town,” recalls Guralnick. “He was instrumental in bringing Otis Redding to Boston for the first time. Even if Skippy’s name wasn’t on the show, he was involved. I used to usher shows and Skippy was always there, present in some way or another.”

White’s reputation and selection made his stores a magnet for more than just Boston-area music fans. Wolf saw firsthand how White’s “amazing taste” drew in some high-profile customers.

“B.B. King, Bobby Blue Bland, they’d stop at Skippy’s. He’d play them something, put on some really rough blues, and I’d go, ‘Skippy, I want one of those, too,’” he says. “When Van Morrison was in Boston, the two of us would hang out in the store and listen to music. We didn’t even have to buy the records; we’d just hang out and listen to songs over and over.”

But White’s stores were more than just a place for someone to buy or listen to a song. A person could come in with one of their own and play it for White in the back of Mass Records. If White liked it or heard potential, he would get it recorded and released.

“Skippy was so involved with music that when he saw artists, he saw opportunities for them to be heard,” says Wolf.

White released material from Boston artists and created his own imprints to fit specific genres — Bluestown for blues singer-guitarist Guitar Nubbit, Silver Cross for gospel acts Lynn Harmonizers and Sons of David, STOP for doo-wop group Sammy and The Del-Lards, and WILD for the more straightforward soul acts.

White would press roughly 3,000 copies of a single to sell in his stores and play them on his WILD show. He’d send copies out to regional DJs and do what he could to get them heard. Some, like blues guitarist Alabama Watson’s “Cost Time” or smooth soul group C-Quinns’ “My Only Love,” got picked up by larger labels and would end up selling a couple thousand copies. Others ended up receiving minimal airplay or went largely unheard and forgotten, until recently.

Boxes of 45s

By the late 1970s, White had five shops open in and around Boston. In 2004, he consolidated them into one, named Skippy White’s, located in Egleston Square. After 60 years in the brick-and-mortar record store business, White closed his final shop in 2020 due to pandemic-exacerbated economic difficulties and a desire to relax at least a bit more in his mid-’80s. Around that time, Joe McEwen, a Boston native, longtime music journalist, and former A&R person for Warner’s Reprise Records who frequented Mass Records during its heyday, had the idea of a compilation highlighting White’s work with Boston soul musicians. He put the idea on Yep Roc’s radar.

Utilizing Yep Roc made sense. Eli “Paperboy” Reed, whose collection of rare 45s and acetates made The Skippy White Story compilation possible, is signed to the label and looking to start his own archival imprint. His stockpile of White-produced records is the source for the entirety of the album.

The Lynn Harmonizers, a gospel group Skippy White recorded on his Silver Cross imprint. (Photo courtesy of Yep Roc Records)

Reed found the 15 songs on The Skippy White Story in a couple of places. Reed befriended White as a teenager in the 1990s while growing up in nearby Brookline, Massachusetts, having learned about his stores from his music critic and record collector father, Howard Husock. In the early 2000s, Cheapo Records, a White-owned store, was closing and had boxes upon boxes of 45s produced by White in its basement. While many were water-damaged, Reed salvaged as many clean copies as he could. He found more tracks in White’s Boston-based warehouse of records.

The tracks Reed compiled and had digitally transferred to produce The Skippy White Story are just a sampling of the available, usable material. But these tracks offer a digestible, accurate snapshot of White’s legacy and willingness to support music and talent he believed in.

“There’s enough for several volumes of music to be released,” says Reed, whose own most recent album, Down Every Road, came out last year on Yep Roc (ND review). “A lot of these he made, people just came into his store and said, ‘I sing too.’ It’s a reflection of his standing in the community. No one he recorded was a professional singer; they were just people who wanted to make a record. He was willing to give those people who came in an opportunity.”

White has specific, detailed memories of how several of the tracks that ended up making The Skippy White Story came to fruition.

“My first record was ‘Sleepwalk’ by Sammy and The Del-Lards,” White says. “I originally met them when I was working at Smilin’ Jack’s College Music Shop. They told me they had a song they were interested in releasing and they got in touch with me when they were ready to record, so we went down to Ace Recording Studio in downtown Boston.

“One day I had blues playing outside and this guy walks in and goes, ‘Do you really sell music like that? Well, I play music like that!’ I told him to go get his guitar and when he came back, we went to my back room and he played the two songs that are on the album,” he says, alluding to the acoustic blues of Guitar Nubbit’s “Georgia Chain Gang” and “Evil Woman Blues.”

“So when I was recording the C-Quinns’ ‘My Only Love,’ I invited Nubbit and told him if we had the time, we’d record his songs. When the people we needed to play the strings still hadn’t arrived and we were on the clock, I said, ‘Nubbit, get over there, get your guitar and start singing!’ Everything with him was done in one take.”

Still on the Air

Reed teamed with Boston Globe journalist Noah Schaffer to interview White and some of the artists that appear on the album and co-wrote detailed liner notes for The Skippy White Story tracing the history of White’s stores and the songs that appear on the set. These, along with essays from Guralnick and Wolf, provide an overview of White’s role in promoting Boston soul and the personal connection he has with members of his community.

In his conversations with White, Reed surmised that “Skippy doesn’t think about his legacy all that much” or have an interest in touting his role in helping to build a community. Even so, Reed has a feeling that White’s been moved by the acknowledgement and kind words this project has received.

“We did an album release show in November and some of the original performers were there. Skippy came and watched and you could tell it meant a lot to him,” says Reed.

Taken as a whole, The Skippy White Story offers context for why White’s stores and various endeavors matter and the vital legacy he created.

“I’m thrilled to see Skippy get the recognition he richly deserves,” says Guralnick. “When you’re talking about him and what he did, it happened on such a small scale physically, just a couple of blocks [in Boston]. But you can’t sum up what a grand scale it happened on emotionally.

“There was this sense of community,” he continues. “I got to be, in my own modest way, part of a community from Skippy and Skippy’s store.”

Today, White’s brick-and-mortar store, concert promoter, and song producer days are behind him, but he remains an active presence and personality. He still sells records, now via eBay and his shop’s Facebook page, which is regularly updated. And he’s still a radio personality, hosting a pair of weekend shows titled The Gospel Train and The Time Tunnel for independent station Urban Heat 98.1 FM in Dedham, Mass. These programs allow him to continue sharing the music and stories that have defined his life.