Iconic Bluegrass Guitarist Tony Rice Dies at Age 69

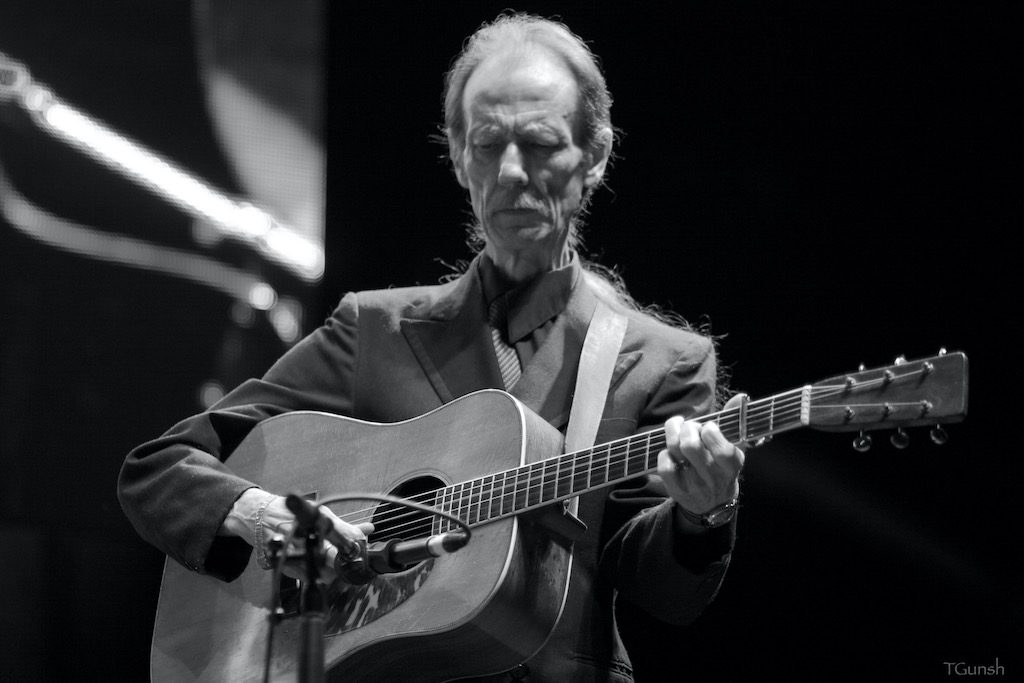

Tony Rice during the International Bluegrass Music Association's World of Bluegrass 2013. (Photo by Todd Gunsher)

The International Bluegrass Music Association announced on its social media channels Saturday that iconic bluegrass guitarist Tony Rice passed away on Christmas Day at his home in Reidsville, North Carolina. He was 69 years old.

“Sometime during Christmas morning while making his coffee, our dear friend and guitar hero Tony Rice passed from this life and made his swift journey to his heavenly home,” friend and collaborator Ricky Skaggs said in a statement authorized by the family, including Rice’s wife, Pam, and their daughter, India.

Rice’s unique style, vast recording catalog, and wide-reaching collaborations were foundational to many pickers in his generation and those that came after.

Born in Virginia, Rice moved with his family to Los Angeles as a child and along with several musical family members was immersed in the bluegrass scene there. Soon the family was traveling and relocating frequently, and Rice, who started playing mandolin, switched to guitar. At a bluegrass festival in North Carolina, he met the Kentucky Colonels’ Clarence White, picking up stylistic tips from him and many other musicians he would meet early in his career, including David Grisman, and developing a virtuosic flatpicking style that folded jazz and other genres into the once-rigid confines of bluegrass.

Over his career, Rice brought his one-of-a-kind picking and singing to ensembles including J.D. Crowe & The New South, David Grisman Quintet, Tony Rice Unit, and the Bluegrass Album Band, and he became known for collaborations with Ricky Skaggs, Norman Blake, Béla Fleck, Peter Rowan, Chris Hillman, and his own brothers, Larry, Wyatt, and Ronnie.

Players and fans will point to different albums in Rice’s catalog as touchstones, but Manzanita, released by Tony Rice Unit in 1979, is considered by many his masterpiece. Backed by Sam Bush, Ricky Skaggs, Jerry Douglas, David Grisman, Darol Anger, and Todd Phillips, Rice marries traditional bluegrass and folk with his wide progressive lens, creating unforgettable versions of classic jam-circle songs like “Little Sadie” and “Blackberry Blossom” that fit perfectly alongside fresher numbers like Merle Travis’ “Nine Pound Hammer” and The Delmore Brothers’ “Blue Railroad Train.”

He won a Grammy award for Best Country Instrumental Performance in 1983 (for The New South’s “Fireball”), and a shelf-full of IBMA awards starting in 1990, when the awards began, and throughout that decade and into the next. He was inducted into the Bluegrass Hall of Fame in 2013.

Rice suffered several health setbacks over the past several decades that restricted his ability to play and perform. In the early 1990s he was diagnosed with dysphonia, a vocal cord condition that severely affect his voice and ability to sing. This decade, he contended with lateral epicondylitis (known as “tennis elbow”) and arthritis, which made playing guitar difficult and painful.

His last public performance on guitar was at during the IBMA’s awards show in 2013; later in the show, he was inducted into the Hall of Fame. I was there, covering the awards show for the local paper in host city Raleigh, North Carolina. Crouched with my laptop in the very back of the cavernous theater, I could barely see Rice, tall and lean, as he walked onstage after the presentation remarks from Bush and Rowan. His brown hair in the ponytail that had become his stylistic signature — always tidy and elegant in its way, but also a statement against bluegrass business as usual — he stood in the spotlight and accepted many minutes of standing ovation from the audience. And then he walked to the podium and spoke, his voice a hoarse rasp. He looked back on his career and was generous in his thanks, but then the speech took a turn no one was expecting.

He referenced two elephants in the room: His own voice struggles, and the fact that acclaimed singer Alison Krauss had recently pulled out of the awards show and a planned IBMA headlining performance because of similar struggles with dysphonia. “One day I woke up and decided to try a few things with my voice, to see if anything at all could happen, even just a little stepping stone toward restoration of the voice. … If my heavenly Father is willing right now I might be able to show you a little bit of what I’ve been working on.”

The crowd roared, and then went pin-drop silent. Rice gathered himself, softly hummed a note, then spoke. And when he did, his voice was back to its familiar baritone, astonishingly smooth, warm, and conveying all of the kindness for which he’d become known over his remarkable career.

“I want to be able to tell Alison that now I am speaking in my real voice. I figure if maybe I can keep this up, that one day again maybe I’ll be able to do what I have missed at times, for 19 years now, which is to express myself poetically through music.”

He spoke for more than five minutes, the audience rapt and, truly, every face in the crowd wet with tears, even as he spoke with wit and humor, which was punctuated by more standing ovations. He ended with this summation of his career and the worldview that made his music what it was and shaped so much of bluegrass and beyond today:

“I think it’s our duty as not only musicians but as participants in this music form that it be like any other music form in history. It’s been allowed to grow and flourish a little bit, but it’s our duty to allow bluegrass music to grow and flourish and at the same time retain the most important part of it. And that is the essence of the sound of real bluegrass music.”

You can watch Rice’s Hall of Fame speech here. I’d encourage you to watch the entire thing to appreciate all his musical accomplishments, but his reference to Krauss and his switch to his natural voice happens around the 11:15 mark.