Improving the Bluegrass Festival Experience for All

Last week I wrote a column I called “It’s Not All about the Music.” My wife, Irene, has taken some exception to that. For her, what comes from the stage at a bluegrass festival is “all about the music.” I take her to mean that her enjoyment of music at a festival can be reduced by the behavior of others.

When she’s in her seat, often near the front and toward the center, she wants to be able to clearly see the performers and listen to their music without having her experience degraded by people expressing their own inner musical selves – obscuring her view by dancing directly before the stage, smoking whatever they’re smoking, and drinking to the point where their behavior becomes uncontrolled.

Irene and I differ in the kind of music we wish to hear, not because of the music itself, but rather because of the behavior of the people enjoying that music as they disregarding the experience and enjoyment of others. Generally speaking, we enjoy a range of acoustic and Americana music with bluegrass and bluegrass-derived music at its center; though I must say, too, that Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Willie Nelson, and Harry Chapin concerts we’ve attended through the years have remained cemented in our memories.

Let’s take a look at some of the issues degrading the music festival experience. I’ll start with smoking.

Since we started attending bluegrass festivals about a dozen years ago, I’ve noticed a significant decline in smoking. Fewer people smoke cigarettes in public areas, and for that, we’re grateful. However, there does seem to be a defiant bunch refusing to adjust their behavior for the comfort of others. At Gettysburg last week, a young man who was smoking stationed his folding beach chair smack between the sand pit – where kids play in the sand all day – and the edge of the major seating area, thereby endangering the health of the kids and the experience of the adults. Since pretty frequent requests about smoking came from the stage, I asked him to put his cigarette out, which he did, with a sneer. Next time I walked past him, he insolently snuffed out his new cigarette, giving me a hate stare.

Meanwhile, a former emcee and local bluegrass celebrity insists on smoking wherever he wishes, whether it’s backstage, which most of the artists hate, or coming out front where he loiters in front of a speaker, providing a lousy example of restraint for the audience. For health, aesthetic, and comfort reasons, I wish festival managers would take this issue more seriously.

One solution we’ve seen work is to erect a fairly remote, very small tent as a designated smoking area. It won’t surprise you that even smokers prefer not to breathe other people’s smoke or have their clothing absorb the odors. As states increasingly take legal steps to eliminate smoking in public places, this issue may resolve itself, but many festivals are likely to remain holdouts.

Bluegrass festivals retain a double standard toward drinking while depriving themselves of a significant income stream and reducing attendance of a demographic they must court to sustain themselves. The standard is that “Family Friendly” pretty much means “No Drinking in Public.” Irene and I frankly don’t care if other people drink. We hardly imbibe at all, and that’s a choice. What we object to, however, is when others’ heavy drinking affects our enjoyment through their reduced inhibitions.

Last year we went to see the Infamous Stringdusters (old friends of ours) at the National Whitewater Center near Charlotte, NC, on a bright, warm Sunday afternoon. The setting was lovely, with the bandstand placed on a sort of island surrounded by rushing water. Both beer and wine were being served by concessions. Attendees stood around drinking beer or shared a bottle of wine on blankets spread out on the ground, where they sat with their, often, young families. We enjoyed a first rate concert in a mellow, relaxed environment. At other festivals, however, we’ve seen the sloppy drunk become pretty obnoxious as the festival reaches a climax on Saturday evening. The difference seems to lie in management setting a standard and maintaining it. It doesn’t take many expulsions from festival grounds for the audience to learn to abide by the limits on behavior and manage their consumption.

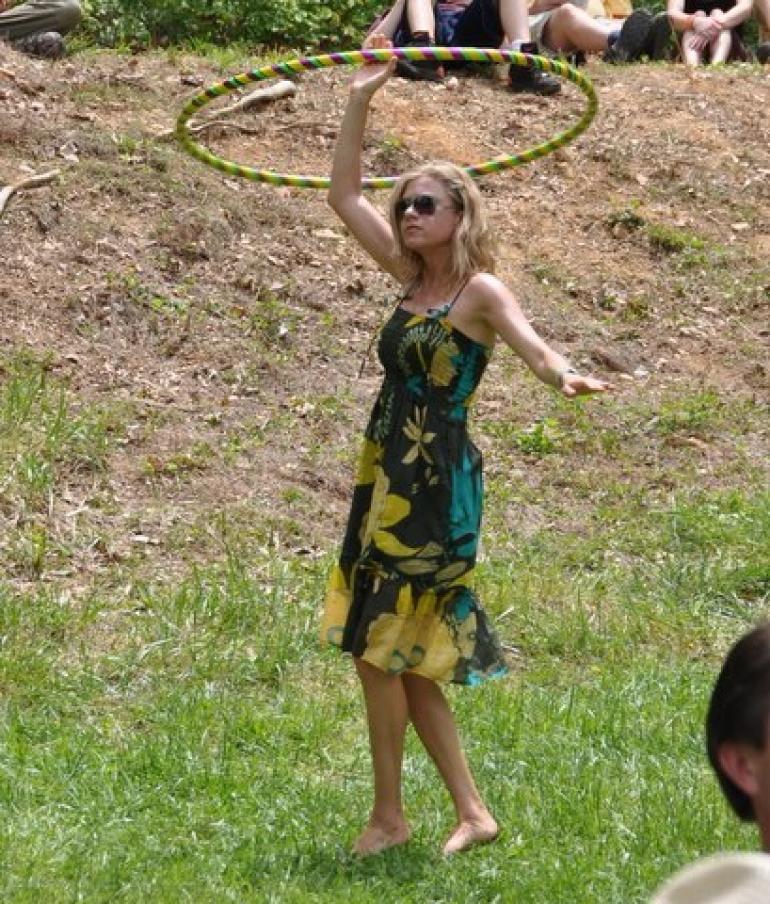

Dancing at festivals represents another area of contention. Dancers seem to wish not only to see, but be seen, leading them to move their gyrations to the front of the stage. They indulge their physical expression of the music’s effect on them where everyone else can see them as they thoughtlessly block the view of the stage. This seems to us to disregard the experience of others with the embrace of their own joy in the music. Dancing (and hula hoops, too) is one end of a continuum that ranges from gentle toe tapping onward. In my opinion, the issue lies not in whether people should be allowed or even encouraged to dance, but where.

Strawberry Park in Preston, CT (where we are this weekend), has a sturdy, raised dance platform that offers a good view of the stage and terrific sound. People dance there all weekend. They enjoy expressing themselves and, as far as I can see, bother no one. Similarly, without any major management effort, dancers at Jenny Brook add color and movement to the scene by choosing to dance along the sides and to the rear of the seated audience. There’s usually plenty of space to dance to one’s heart’s content, if expression and personal experience rather than display are the objective.

I think establishing a culture of behavior and then enforcing it gently but firmly could be the answer to managing these things while increasing the likelihood that everyone will have a grand experience at a festival. It only takes a few drunks or obnoxious, insistent smokers to ruin the experience of others.

Darrel Adkins, the promoter of Musicians Against Childhood Cancer, held every July near Columbus, OH, speaks to the audience several times during the festival about the experience while offering places to dance and purchase beer. Then he provides sufficient security so that people whose behavior exceeds his guidelines are either helped back to their campsites or ejected from the festival. There’s never a feeling of excessive rule-keeping, and there’s always a sense of fun and celebration. I’m sure many other festivals maintain such standards. When festival managers seek to cater to every sort of behavior without considering the overall experience for the majority of those paying the bills, the festival risks falling apart.

As festival season rolls into full swing this summer, try to think about the way your own behavior can be modified to help assure that a high quality experience can be had by all. It might even increase your own enjoyment.