Free Like a Bird

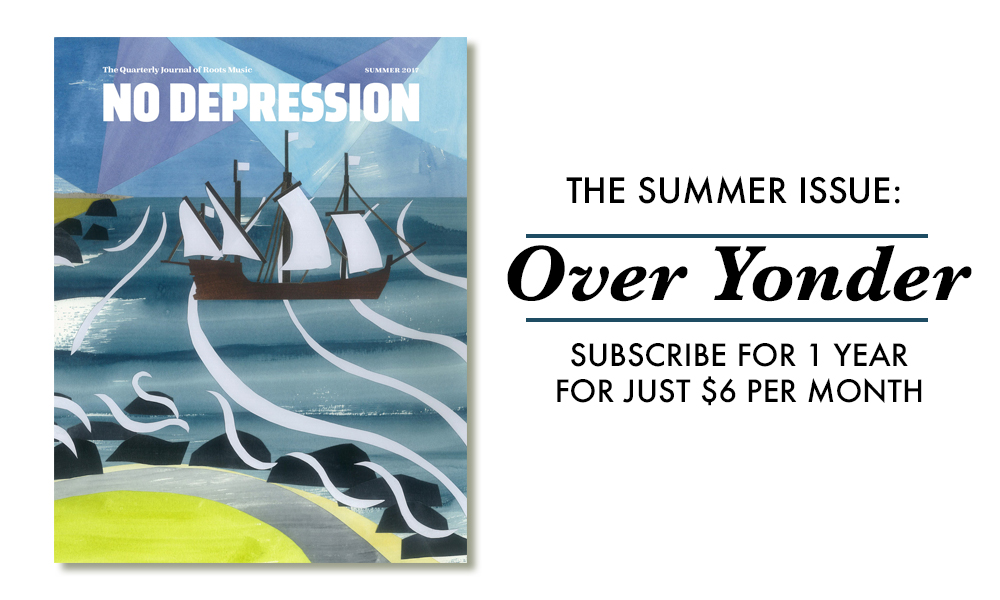

Editor’s note: Following is an interview between No Depression contributing writer Megan Romer and Aurelio Martinez, a Garifuna immigrant from Honduras who now lives and makes music in New York City. This interview was conducted as part of research for an article Romer wrote for our Summer 2017 issue of No Depression in print, wherein she explored the relationship between a handful of immigrant communities in New York and how the roots music from their homeland has provided a vehicle for them, and a connection for their community, in the United States. In addition to Aurelio, Megan spoke with Ani Cordero, Janka Nabay, and Sinkane. The resulting article is only available in print. Subscribe today for just $6 per month, to receive your copy. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Megan Romer: Your music has always been political. But it’s not only your music — you were a congressman in Honduras, right? [Aurelio was the first black member of the National Congress of Honduras.]

Aurelio Martinez: [laughs] Oh yes, my music sometimes is political, but in my life I have much to say about the politics of my country.

[Those are] different things, you know — the politics of parties and the social politics. But yes, I involved myself for eight years in party politics, to make [issues] in our towns and villages be known. [That was] for a different intention, for a different reason. But, you know, for me in the final, it’s the same thing. I do politics for the party because I try to bring inclusion, less discrimination, to talk about minority people in front of power. …

I learned politics because of music. I was my own politician! [Laughs] Music [gave] me the support to become a politician. We have politics when we are born, we have politics every day, our whole life. But for me, music is my important thing in my life. I think before I was born, I was a musician, in my mom’s belly.

It’s really important to be aware of the way music can connect immigrant communities, for one, but the music can also provide an opportunity for Americans — especially white Americans — to understand that people elsewhere in the world aren’t scary. There’s a pretty big Garifuna community in New York. … Do you play a lot in New York, for the Garifuna community? Or do you find your audiences are more American-born?

You know, I do music in two ways. I have an international project of Garifuna music, and sometimes I play in Manhattan — Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, different places. [There,] it’s a little bit more [of a] white crowd. Sometimes I play local music, as we call “punta rock.” [That’s] a little more electronic, and it’s the way we play the music in our communities. So I do three shows in New York every year, of local music, mostly in the Bronx. [And also] around Houston, New Orleans, Boston, in Texas, in L.A. [When I play] international music, it’s mostly the white people who come to my concerts.

It’s interesting that, even in 2017, the crowds separate themselves so much.

Yeah, of course.

You know, we have a segment of the Garifuna people here in New York who don’t like to come to the house parties. They’ll come to Carnegie Hall, but they cannot afford it, so they prefer to be part of the [stage] crew at that.

It’s nice when music can speak across lines and cultures. Music can mean something when you’re abroad and it’s a sound from home, but it can also mean something to somebody who’s never been to Honduras or Belize, who doesn’t know anything about that part of the world, but who can feel the pulse of the culture in the music.

Yeah. When I start to do the international version of Garifuna music, I know I’m going to fight a little bit with the Garifuna community. Because, see, we prefer to listen to our music in our way — the Garifuna way. But when you introduce the Garifuna music to other cultures, you have to find other sounds, and maybe a style [as an entry point] … and people don’t like to see the music used in this way. But I know what I’m doing! I know what I’m trying to find! It’s a special exchange.

Garifuna people [are] a very musical people. We like to listen to music all night, and dance, jump around all night, [hear] drums all night long. But for non-Garifuna people, it’s a little bit hard, because you don’t understand the lyrics. … When I introduce my music to an international crowd, I have to do arrangements in an international way, [and] the Garifuna people, at the beginning, don’t agree. But little by little, people understand what you’re doing.

It is important to be a good translator, not just with language, but with music, too. That always separates the different levels of international artists, in terms of crossover success: The ones who can make the music digestible for diverse audiences seem to do better, whether that means explaining it well in words, or some kind of actual musical crossover.

The artistic opportunity is so beautiful. [You have] the opportunity to say, to introduce, to change, to make nice, to talk about social problems. The music has a lot of opportunity to bring something different to people around the world, to connect people, you know? To feel other cultures, to feel another kind of life, to feel other people. I love to do that!

I want to use the music — my music — to find freedom. To connect people.

Rght now, in America, we’re seeing a return of fear toward other cultures. I mean, it’s always been here, it’s gotten loud again lately. I have some hope that music might be one of the answers to that fear — to teach people that there are different people around the world, and you don’t need to be afraid of them. You’re a permanent resident. Do you have concerns about being an immigrant in the United States right now, with our political and cultural situation?

When I write, I’m talking about social problems. I talk about be[ing] an immigrant. I talk about the huge problems we have around the world. And [I talk about] some mentalities — like our President we have here in the United States. … Now we are talking about the wall between Mexico and the United States. And everywhere on the planet, people separate people by walls. And I think, you know, we have to be like a bird.

Fly above?

Yes! Fly, fly, fly between countries.

Countries don’t know about borders, about walls. Humans have to be like animals, like birds who can fly between country and country. We have to be free.

I understand the security between country and country — it’s a human thing. But God created one world for everybody, and we have to be free to connect our homes and our people. Sometimes, this kind of discrimination we have, if you believe in God, it’s impossible to live in this way. So I try to talk in my concerts about this situation — a dangerous situation, a difficult situation. It’s a little bit of a danger for me, but I don’t care about who is upset by what I say, when more people are being upset in a bad way. So I’m going to be with immigrants, because I come from immigrant people.

I mean, if you’re going to talk about immigrants, [the history of] my community comes from the slave history. We come from Africa, to some distant Caribbean island, and then some people sent our community to Central America. … They forced the African people to come to America, to come to Europe. They forced them to leave their family to come here to work. And now, it’s a problem to be an immigrant!?

We have to find a balance between humans. We have to find the center of problems, to find a solution.

This is my message at this moment: The situation we have in our world now, the reality of the world we live in now … I’m very scared about the situation we have. Because you know, we people don’t have no respect for life now. Somebody will kill many people and we don’t have no reason why. We ask why, but people are just sick sometimes. We have to find more love to bring to people, we have to understand. If we don’t have the ability to understand, what do we have? We have to try to understand!

I wish it was simple, that there were simple ways to teach this to people. There’s no really easy way, is there? But we have to try anyway, right?

You know, sometimes, I feel people like me … to feel the problems that people have, I have to go and see people in [their] places. To feel my body, you have to be in my shoes!