Interview with Meg Hutchinson: A Voice to Be Heard

Meg Hutchinson is an inspiration in so many ways. Not only is she a fabulous poet and fantastic singer-songwriter but she is a champion — an active advocate for mental health awareness. Having suffered from mental health issues herself, she is keenly aware of what it’s like and is a powerful speaker on the subject.

Kathy Sands-Boehmer: When did you first start writing – poems, stories, songs — that weren’t school-related?

Meg Hutchinson: I can remember writing stories and poems from before I could write. My mom is a poet. She would let me dictate stories to her when I was about four or five and she’d patiently write them all out for me. There was an epic saga about losing my doll “Fellow” in the forest. There was a recap of a friend’s birthday party, and various other things that five year olds find worthy of report.

Once I learned how to write, my mom and I had a ritual of leaving each other letters under our pillows on nights where she had to go out. We have a huge folder of our correspondence.

I inherited my paternal grandmother’s guitar when I was about nine years old. I took some lessons for a year. In eighth grade, I wrote my first song. It was about Apartheid and South Africa. I sang it at the school talent show. After I walked offstage, I burst into tears. My friends were patting me on the back saying, “What’s wrong? You did a good job!” But I was crying because it was like coming home. I knew what I was supposed to do. I walked out into the schoolyard with my guitar and I remember it was snowing and I was crying with happiness at having found a familiar place in myself and in the world.

When did you start sharing your writing with others?

The next week, I decided I would start my music career and I went down to the open mic at the local Deli. I sang that same song, my only song, “Freedom’s Ocean.”

Do you experience writing as a meditation of sorts – as a way to make sense of your world and that of the world around us?

I guess from a very young age, it was the best way to create some kind of order to my experience. Writing was a good way to communicate in my household. My two sisters were super talkative and brilliant and I was the rather quiet, spacey middle child. Writing was a good way for my slower mind to form thoughts over time. In that sense, it was already a meditative practice.

You grew up in Western Massachusetts, which is a somewhat rural part of New England.Do you think you would be a different person today if you had grown up in a large city?

Yes, absolutely. I grew up close to the earth. I grew up lying in the grass, in the moss, in the leaves. I grew up with my hands in the mud and running around barefoot everywhere, collecting things. I grew up with a sense that there was a natural kind of silence in the world and a natural space between events. Every day after school we were allowed to just run out the back door into this great forest and just play til suppertime. That silence and independence would have been very hard to find in city playgrounds.

What kind of gigs did you play when you first started playing your music before audiences? id you play in the subways before you ever played in a club? Would you say that busking is a good way to test out your stamina for the musician’s life?

My first regular gig was in a bar in Pittsfield, MA. I was 17 and they gave me Tuesday nights. The owner was super sweet. The audience was a bit rough around the edges — mostly men there for dart league night, which also happened to be on Tuesdays.

I sang my heart out there. The more that people drank the more wayward the darts would get. It was never dull there.

Later I started playing in Borders bookstores all over the northeast. It actually prepared me to play the subways. You have to win people over in that environment. One person at a time. You do that by finding your own joy there, you know?

The espresso machine would be grinding away, and most people in the cafe would be reading and eating. Then I’d start singing. I’d sing my heart out. I’d be loving every minute of it. I was really pretty terrible back then, but I was passionate about what music was doing for me. It was helping me. People noticed that. They put their books down.

When I moved to Boston, I asked Martin Sexton what the best thing I could do for my career was. He told me to play the subway. It was the greatest education I could have gotten.

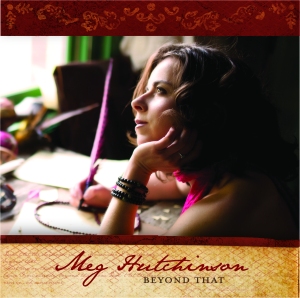

Your newest album, Beyond That, has been described as your “most modern and intricate” production to date. What makes it modern and intricate?

I spent the last few years learning Pro Tools recording software and re-learning the piano. This gave me so much freedom to write in new forms, in new ways. I felt free of former song structures and felt ready to explore.

I also wanted to play with different sound options. I’d always loved David Gray’s White Ladder album and I wanted to find that combination of organic sounds, and get some of those synthetic beats and layers that I’d found so compelling on that record.

You’ve won so many songwriting and festival competitions. Does any one stand out as a special one to you?

Kerrville was the turning point. That was the first major song competition I won. I was 22 and had driven all the way to Texas. I didn’t even care that I was so poor I had to sleep in the car on the way there. I had my dog Osa along with me and I was just invigorated and felt so alive out there on the road. When I won that award, it opened a door and bigger things started happening in my career.

You’ve been very open about your struggles with mental health. Have you discovered that this openness has enriched your life and made you a stronger individual?

Yes. In the eight years I’ve been open about living with Bipolar illness, I’ve been amazed at how much closer I’ve felt to people around me. I guess I had somehow believed that I was supposed to be perfect. I was really good at things, at sports and school. I was a really happy and sunny kid. When I began to struggle at age 19, I kept it hidden as much as possible. I thought it would make me unlovable. The greatest discovery was to make the choice to be open and to find myself feeling more loved than ever before.

You are a noted keynote speaker and have been asked to give talks about mental health issues at universities and hospitals around the country. Did you ever imagine that one day you would be helping others by telling your own story?

No, it has been one of the great surprises of my life. It’s amazing to go from someone who was too ashamed to seek help, to being someone who gets up on stage and talks about it all.

The choice to speak didn’t feel comfortable in the beginning. But I felt a deep sense of responsibility. When I was going through my lowest point in my life eight years ago, I felt so much shame about diagnosis, and so little belief that my brain would ever start working well again. That shame and that fear about the future, combined with the illness, put me at such huge risk for suicide.

We can’t eliminate these illnesses, at least not yet. But I do believe we can get rid of the shame and get rid of the fear and discrimination and encourage help-seeking. I think if we change those things, we can make it so much easier for people to recover. Especially young people. These illnesses impact young people so tragically and abruptly.

Please tell us about the film you’re working on. It is an extension of the lectures that you give…

I’m working with Ezzie Films, whose mission is to document the positive contributions of music to society. I met founder Todd Kwait when I was invited to appear in a recent film of his For The Love Of The Music, about the Cambridge folk scene and the early days of Club 47, which is now Club Passim.

Our film is called Pack Up Your Sorrows, in honor of that song by Richard Farina that I’ve loved my whole life. The chorus goes, “But if somehow you could pack up your sorrows, and give them all to me, You would lose them, I know how to use them, Give them all to me.”

The film is told through the lens of my personal story. It explores the topics dearest to my heart: the role of nature, meditation and creativity in healing, the value of mindfulness in education, the importance of mental health literacy and wellness, and how all these elements converge in making the world a better place. I got to interview leading psychologists, neuroscientists, authors, historians, and spiritual teachers, including many of my heroes. We’re about to start editing and expect to release the film in early 2015.

Last but not least, we need to hear about your dog, Austin. He sounds like a remarkable furry friend.

Austin is a 1 1/2 year-old brindle pitbull mix. He had a tragic start to his life and was rescued last summer from a severely abusive home. Immediately, the local shelter could see his sweet spirit and humor. They called my friends at Out of The Pits in Albany, NY. The president of Out of the Pits, Cydney Cross, was my first music manager twenty years ago and taught me all about the music business and got me my first gigs when I was 17. Out of the Pits took him into their custody and got him the surgery he needed and many months of loving foster care. I followed his story on their website from August until December.

On the anniversary of my dog Osa’s death, I had a dream that she and Austin came running across the lawn together. In the dream, Austin sat down in front of me and I could feel the presence of this really incredible heart. He just stared at me. I called them the next morning and he came home with me at Christmas. He’s had a lot to learn about the world, and a lot of fears to overcome, but his goofiness and willingness to learn were just completely enchanting from the start.

His biggest issue is separation anxiety. Unlike my last dog, he can’t stay alone in a green room during shows. He cries and wails for me and is like the Houdini of dogs. Our compromise is that he sleeps on stage during my shows now. He loves folk music. The minute I start to sing, he falls fast asleep. I often have to wake him up at the set break.

He’s a good friend and a good teacher. We spend hours in the woods every day. He reminds me of the spirit’s capacity for resilience and recovery. He reminds me to pay attention to the small things along the way.

Learn more about Meg Hutchinson at her website.