Moving House

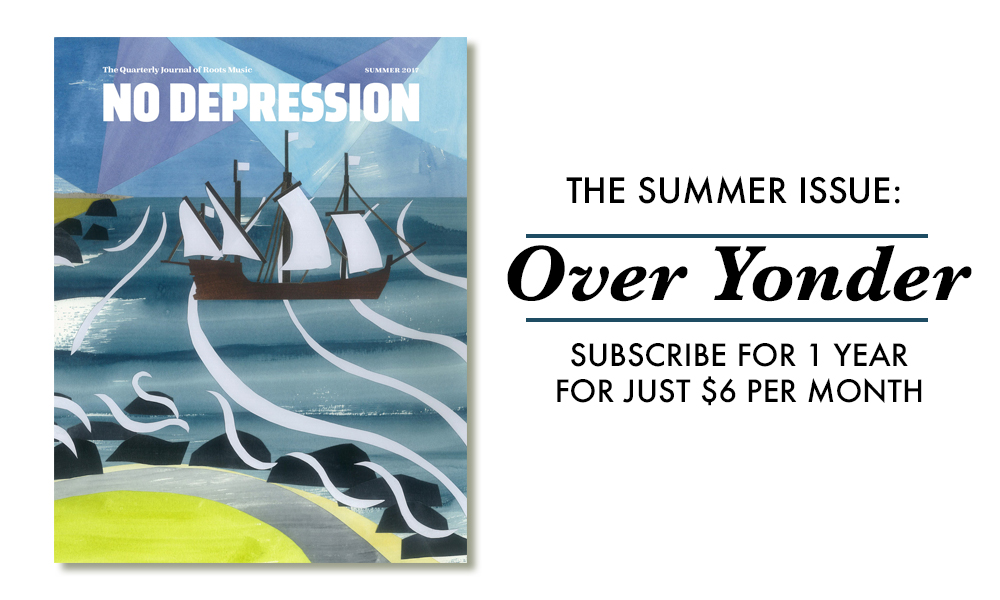

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in our Summer 2016/Homegrown issue of No Depression in print. It has been digitized as part of our summer subscription drive, though articles in the ND journal are typically exclusive to print. Subscribe today for just $6 per month and never miss another issue.

* *

It’s impossible not to notice Elizabeth Cook. I did the first time I saw her at Nashville’s Exit/In one Tuesday night, at Billy Block’s Western Beat Barn Dance, during the late 1990s. She had just started to emerge on the Nashville singer-songwriter scene. She was blond, beautiful, seemingly a little on the shy side, sporting cat-eye glasses, and wielding a voice that made my ears perk up and my heart swell all at the same time. It was obvious that she was a serious talent, though there was an air about her that suggested something else running beneath the surface, something beyond her voice and beauty.

We got to know each other slowly but surely. We saw each other at parties and gatherings and commiserated about the degradation of auditioning for this record label or that publisher around town. We moaned and complained, but never dwelled on it. We knew it was only part of the game we’d signed up to play, and hopefully win.

As Elizabeth and I grew to be friends, I found out she wasn’t shy at all, and what I’d intuited beneath the surface turned out to be a big brain and a deep soul. She was an Artist, with a capital A.

Elizabeth has since carved out a career for herself that is not only successful by anyone’s measuring stick, but enviable as well. She’s racked up over 400 appearances on the Grand Ole Opry to date (she quit counting after her daddy died). She hosts a beloved program on Sirius XM’s Outlaw Country channel called Apron Strings and is a certifiable radio star, as much as anyone can be these days. She’s played hundreds of shows, written plenty of songs, and made well-received albums. She’s never made a note of music she couldn’t stand by, and has been authentic every step of the way. But it’s been six years since Welder, her last bold and brave full-length album, and four since Gospel Plow, an EP inspired by the church of her childhood.

A lot has happened since those days.

One of the things I’ve learned in the years since I first met Elizabeth is this: If you’re an Artist with a capital A, you’re going to be paying attention. And if you’re paying attention, you’re going to change. I’ll leave the math on that up to y’all. But I will tell you she has a new record in the can called Exodus of Venus. It’s coming your way soon. And once again, it’s going to be impossible not to notice Elizabeth Cook.

She and I caught up over FaceTime this spring [2016]. She was at her home in Nashville, and I was at mine in New York City.

Elizabeth Cook: Look at what I woke up to this morning. I don’t know if you can see it, but it snowed cherry blossoms. [She’s out in her yard.]

Alison Moorer: That’s gorgeous. … I want to talk to you about this new record and a couple other things.

So. Exodus of Venus. I’ve listened to it over and over, and it’s just super deep sounding and big, and deeply groovy. It’s the biggest piece of music I’ve heard from you. … It’s rockier and more atmospheric. It’s lyrically deep and insightful. I hear you cutting loose, I hear you asking questions, I hear you accepting yourself and the world, I hear you being brave.

[Laughs.] Yeah, I blew my shit up, you know. It’s taken balls to do it. And I still don’t know what I’m doing. I’m feeling pretty, you know, freaked out, but better. [I have] more solid footing all the time. And making this record and putting it out is part of that process, as you know.

Well, tell me, if you want to … about the blowing up. I know what blowing up feels like. I’ve done it myself.

I bet you do! You know, I had the good fortune for a long time in my life of being shielded from tragedy, unlike so many folks. And then all of a sudden, over about a two-year period, my daddy died, my mother-in-law died, my father-in-law died, my brother-in-law died, my brother died, the farm burned down, my sister got a divorce, and then I got a divorce. All of that happened in a really short amount of time. So it seemed like every six weeks I was nursing somebody on their deathbed, or going to a funeral, or in divorce court. And those are dark places to reside in for that long a time.

Well, you know I always say that sometimes life changes things for you, whether or not you’re conscious of anything needing changing. Sometimes the universe just takes over. It’s pretty painful to change, and it takes a lot of strength to get through it. I hear a lot of strength and fighting back on Exodus of Venus, and that’s so exciting to me because the greatest art is personal. That’s why we make it. It’s our way of coping, but it’s also our way of reaching out to other people and saying “you’re not alone.”

Yeah! It’s our job. That is the assignment.

The record just sounds beautiful, the songs are great, this sounds to me like a country rock outlaw record.

Dexter Green [producer] had a ton to do with that. I don’t know how to make those sounds and do that with guitar and write riffs and stuff, so… It allowed me to focus on other things to not have to do that part.

The worrying about the producing part?

Yeah. … I co-wrote most of the record with Dexter, and it was the process of him playing me some deep, dark groove on the guitar that I would just start singing over, and it would speak to me, and it would have this really cool sound, and I would start saying something over it and then dig in the journals for the lyrics. It was so easy — and rewarding. I had never heard my music sound like that before. I was just really enjoying it. I’m enjoying playing the music live a lot.

Let’s talk about Dexter a minute. How did you meet him and what makes you click?

Yeah, what makes us click? I mean, chemistry! I was not gonna do this, you know. I had plenty of things to get together and focus on and coupling up again was not something that made a lot of sense on paper. But again, it was one of those things that just happened. There’s a line in “Exodus of Venus”: “Far-away lands suffered a plague the minute you put your hand on my leg.”

I heard that and said, “Uh huh. Been there.”

Sexy talk! I’d known him for a long time. Jason Isbell and I had recorded at his house, so he had helped me record things there in the neighborhood when I just needed something done quickly, but I really didn’t know what he did. He’s kind of a quiet guy. I knew he had a studio and was nice and cute and he would help me sometimes. One night he gave me a ride home from the bar and …

Oh hell.

Yeah. I was like “Damn it!” I was changing management, breaking that bond. … I lost everyone around me. Friends fell away, the industry fell away, things got thin. It’s been thin! And that was right when we got together. That chapter of chaos was about to start.

I always say be careful who you make music with, you might end up moving house.

[Laughs.] Amen.

Singing and making music with people is such a visceral experience that you can’t help but connect. And when there’s a spark there anyway, watch out. Tell me where you recorded this record.

We made it at Sound Emporium [in Nashville]. We had a wonderful week in there with great players. …

I know. Willie Weeks, Matt Chamberlain, Buddy Miller, Patty Loveless … this is a great cast.

Ridiculous.

Getting in the studio and making stuff up is just so much fun.

Yeah. And I knew that. I knew that when all the rehab stuff went down I was like, this is not it.

Do you want to talk about that? … I remember worrying about you and sending you a note saying such after seeing you at the Americana Music Awards in 2014, when all the rumors started flying around. I thought, “What?”

Oh right. You’ve known me too long.

Right. Folks might be surprised to hear this but you and I are sorority sisters. We are both Kappa Deltas! We don’t drink in our letters or smoke standing up. I just didn’t think what I was hearing was the whole story.

Right. I had definitely gotten too skinny. It was from stress — it wasn’t from dieting.

Well, death will do that to you.

Yes. And divorce! I called it the Divorce and Death Diet. Then there were medications and drugs that I was partaking in to cope, but I wasn’t directly addicted to any one thing. I was just medicating randomly with different stuff, and I made some bad choices.

That day in particular I [accidentally] took a toxic mix of pills. But I was still fine. I went and did all my gigs. I did everything I was supposed to do that day, I didn’t understand. But the people who were around me that had fallen away, that then all of sudden were in town and saw me for the first time in six months, cancelled my tour, [which was supposed to be] my nut for the rest of the year. They didn’t want me getting on a tour bus with Todd Snider for a month. They thought that maybe I was anorexic, or bulimic – they just didn’t know.

They all teamed up and presented the rehab idea as a vacation and said, “If something’s wrong then we’ll get to the bottom of it, and if not you’ll get a vacation.”

Oh my God, that was traumatizing. I was institutionalized and I don’t do well with that. It wasn’t for me. But it serves a purpose and I learned a lot, and I look back now and I think it was probably supposed to happen.

That particular thing has saved God knows how many lives, but you might’ve just needed a break.

It was a fake spa. When I got in there, they weighed me in the dark, they wouldn’t tell me if I was gaining or losing. [They put me on] a very regimented diet and I was starving all the time. My appetite was coming back. They thought I was purging because even with the protein shakes, etc., I wasn’t gaining weight fast enough according to their science. I got in trouble for wearing my sunglasses inside because I had a migraine — shit like that. And I just didn’t do well with it. But we [ruled out] some things out that weren’t wrong, so that was good. I learned a lot and moved on.

That particular thing — dealing with our bodies as women, who are looked at a lot — has always been a struggle for me. When I saw you that night I thought you looked thin, but I’ve been too thin before and it doesn’t scare me as much as it does other people. I’ve been accused of having an eating disorder, too. It’s a difficult thing to be picked apart so much. Now we’re getting older. There comes a time when you think, ”This is who I am, this is what I look like, I’m going to try to look the best I can but I’m not going to expect to look like I did when I was 25 anymore, nor should anyone else expect that of me.”

Right. Absolutely. I mean when you’re bred to believe that your appearance is part of your value …

We could talk for days about that.

Add in being an entertainer. Then try and have integrity as an artist. And balance how good-looking you can be. There’s a lot of conflicting information there. I’m fortunate to have strong sisters and beautiful people in my family, and I’ve just come to peace with a lot of things.

I’m supposed to — and women, I believe, are supposed to — pass into a different way of looking and feeling and feminine energy [as we age]. It just shifts. I’m okay with that.

I enjoy feeling sexual. I’m not one to believe that we should sacrifice our sexual power and femininity in the name of feminism. I believe it’s biological and it’s part of a power that there is nothing wrong with embracing and having fun with. I enjoy it when I feel like I look good. So I’m going to keep putting effort into it, I guess.

[Now, for me, feeling good is] more and more about energy, spirit, and presence, instead of just the aesthetics. It’s just shifting. I feel like what we as women have to offer shifts as we get older. It goes from the physical to the metaphysical. That’s natural and can be awesome.

It becomes more about your insides showing up on your outside. And once you get comfortable in your skin, it’s way easier to let that happen.

I want to talk to you about how losing your parents affected your artistry. You know I lost mine, too, so something that has always been a theme in my life is dreaming their dreams, saying their sayings, living my life, in a way, for them, [and] carrying out their wishes because they aren’t here to do it. I know you were very close to your parents and they were musical, and were supportive of your musical dreams, but I think also probably pushed you to do it. Correct me if I’m wrong.

Well, it was an earnest thing that came from love and excitement and pride. But yes. And they didn’t realize it. And that’s something I’ve learned in therapy. They loved me and that was genuine, and they thought they were doing great and were just so proud. But I was being used.

I’ll never forget hearing, “Mama you wanted to be a singer, too.”

Oh, wow. That’s an old one. But, yeah. I totally did it for them. Right before Mama died, I had just started writing for the Welder album, 2008, and I had written “El Camino,” and I played it for Mama in my car, driving her to the grocery store, and her response was, “Elizabeth, really.”

Do you feel like not having them around has freed you? Would you have made Exodus of Venus, if they were still alive?

No. They were more and more confused about my career because they didn’t understand — to them you’re either Reba McEntire or the local lounge singer, with no in-between. It was hard for them to understand how that [in-between] could exist, and that’s where I’ve existed.

[At the end,] they started to find peace with that, so I think I was freeing up somewhat anyway because they had to start letting go of the idea that I wasn’t going to be Reba McEntire.

But “Heroin Addict Sister?” I don’t know if I would’ve written that while my mother was alive. It was so important to her that her children get along. I didn’t plan it, I didn’t wait on purpose. I just realized that I probably would not have naturally gone there. I have the disease to please, and of course I wanted to please my parents. That stays with you. When they passed it was like being home alone. I’ve become musically unsupervised.

I always say when you’re an orphan you’ve got no one to answer to and nowhere to go for Christmas. … It’s a tradeoff. There is a freedom that comes with losing your folks. It’s a sad freedom, but it is still freedom. You feel loosened from those expectations. You also don’t get the approval that you crave so much.

That’s right. That’s right.

Let’s talk about “Tabitha Tuders’ Mama.” I lost it when I heard that one. I have a little boy and I can’t stand the thought of losing him, as no parent can. When I first listened to the song, I wondered how you did it, but then I decided that you don’t have to be a mama to feel empathy for one. Tell me what inspired you to write it.

I think that I saw some parallels between this working class, blue-collar, lower economic class family and my family.

This was my mother’s greatest fear, that I would get snatched. I almost did. When I was 11, a guy tried to pick me up in his car. When I realized that he was creepy, I turned around and ran, but he went for me. I ran, and he took off. I think about — had he succeeded — the situation my family would’ve found themselves in.

I believe there’s a stigma attached to the economics of the situation. Why does it feel like it’s more tragic to lose a rich little girl than a poor one? And I [wonder], “Are black children not abducted?” Cause I don’t ever see anything about that. So there’s almost a value assigned, and we were a poor family. … What if the town would’ve thought, because we were trashy or whatever they thought about us, that there was some shenanigan that trashy people partake in or I had run off with some older man or something.

I look at pictures of this little girl [Tabitha Tuders, a 13-year-old who was abducted in Nashville in 2003], I’ve got them right here, it’s like … She’s holding an alligator. … I don’t know, she’s a little girl. And I just felt like there was an injustice in the stigma attached to it because [of the] economics.

When you go down that street now, with all that’s happening with real estate in East Nashville, the big condo things are on both sides of their house. The pressure they must be under — how many developers want to knock their house down? But that’s her home. And what if she tries to come home?

Yeah. That’s pretty profound. But you’ve never shied away from commentary. You do it with “Evacuation” and “Methadone Blues” on this album, and you’ve done it with earlier songs. I so appreciate it because it’s so hard to do successfully and without being preachy. You do it very well.

All right sister, well best of luck and love with it all. It’s been so good to talk to you today. The record is amazing and I’m so proud of you.

I wanna know how you’re doing!

Let me turn off the tape recorder.