Jazz Singer Mark Murphy (1932-2015), “The Next Sinatra,” Did It His Way

Call me crazy, but I see a little of Crazy Horse in Mark Murphy, the magnificent and fearless jazz singer who died October 22 at 83, of complications of pneumonia. More specifically, I see Murphy in the somewhat quixotic Crazy Horse Memorial sculpture, which I was reminded of while searching for news about Murphy in The New York Times. This was May of last year, but I had inklings about Murphy’s death, as he’d been ill for a while. At the time, I stumbled on an obit for 87-year-old Ruth Ziolkowski, who carried on her sculptor husband Korczak Ziolokowski’s dream. He had worked for years on his massive likeness of the great Lakota warrior Crazy Horse carved into the Black Hills of South Dakota.

In a sense, Ruth succeeded, because The Crazy Horse Memorial draws more than a million visitors a year, as is. And yet, her husband’s ultimately hoped to carve a full figure of Crazy Horse on his horse, out of the rock, and to date all that is visible is the famous Lakota’s 90-foot-tall head, impressive as that is. 1

With Murphy what counted was mainly his leonine head — what came out of his mouth from his brain, and his huge heart and soul.

And yet so much of him, like the full Crazy Horse figure, remained underground — his proper role as a highly influential innovator, and arguably the greatest male jazz singer of his generation (and right there with the greatest females). I’ve found that his historical recognition appears under-served in light of his somewhat controversial life, talent, dedication and courage. Of course, there’s controversy with the Lakota warrior because he defeated Gen. George Custer at the Battle of Little Big Horn. Crazy Horse fought against the US government’s removal — and effective permanent internment — of Native American tribes to reservations. The issue hangs on your opinion of who the bad guys were in that battle.

And part of the craziness in Mark Murphy’s life was how far he stuck his neck out in the winds of derision — his artistic and personal risks. He isn’t unappreciated in the music business — he earned six Grammy nominations for Best Jazz Vocal Performance. But he never won the award.

As noted jazz singer Jackie Allen, a student of the art form, told me, “Murphy was being groomed to be the next Sinatra, but he was just too far out. And I’m sure his being gay didn’t help him.”

So, part of being far out was coming out, as a gay man, very early in his career, which probably doomed his prospects as the next Sinatra, especially as old blue eyes had perpetuated the retro-straight-tough guy persona.

So Murphy fought for gay male jazz singers and performers from being culturally exiled.

Although things have improved, jazz remains straight male-dominated and the same is true of jazz critics and historians. And I have to wonder if Murphy’s neglect among major jazz critics and historians has anything to do with his genetic persuasion (as research has shown about gayness). Another of Murphy’s gay contemporaries, the exquisite singer-pianist Andy Bey, had a terrible time dealing with his sexual orientation in his chosen career, something illuminated in a compelling PBS documentary film on him.

With Murphy, the inside story remains comparatively clouded. He may epitomize the cognitive dissonance that exists between jazz singers and, to an informal manner, jazz musicians, as symbiotic as their relationship is. Singers often get their band mates their most consistent and best-paying gigs. Yet too often musicians (I risk a stereotype, I admit) complain of gigs with a “chick singer.” The implication is the singer’s presumed inability to convincingly negotiate complicated chord changes or to sing in an improvisational manner or to scat sing, or her burdening musicians with renditions of hoary and sentimental standards.

Because male jazz singers are much rarer than female singers (an essay subject unto itself) this problematic relationship is less clearly articulated and understood, but it’s safe to think that a somewhat same bandstand bias exists against the male singer (Murphy also played piano and sometimes did his own horn arrangements). What is striking and empirically evident is the lack of acknowledgment that Mark Murphy gets among jazz historians and critics who are assumed to be authoritative.

But first, let’s reference a jazz singer’s opinion. Jackie Allen, once musically obsessed with Murphy, recorded a duet version of a signature Murphy song: “The Bad and the Beautiful” with the late singer’s number one artistic acolyte, Grammy-winning singer Kurt Elling, on her 2003 album The Men in My Life.

“I’d never heard anyone else sing it – or anyone else who could sing it, because it spans a couple of octaves,” Allen wrote in her liner notes. “So it was something I always wanted to do.”

So Murphy was “bad” as in problematic in some folks minds. But man, was he bad — and beautiful (as an artist and as a man, coming from this straight journalist’s judgement.)!

Some people complained that Murphy sometimes over-dramatized. If this criticism derived at all from the homophobic bias against “drama queens,” it’s good to remember that singing is always partly music-making and partly acting. A happily married heterosexual friend of mine, Bill Camplin, who’s a brilliant jazz-inflected folk singer, calls himself a “drama queen.” And I’m glad, because a sense of drama is essential to his art, as it was to Murphy’s and any jazz singer’s.

Murphy could go from deeply simmering dulcet tones to a soaring trumpet-strong cry with all too much ease for some, but he often carried a song to uncharted heights in the process. I think it’s a confusion or perhaps anti-gay bias that denies the artistic necessity to be honesty vulnerable and expressive with a man’s self.

Perhaps symptomatic of this is a comment that the highly estimable critic-historian Francis Davis made: “I thought it was amusing that Mark Murphy, a singer fans adore him for his alleged spontaneity, but whom I find unbearably ‘jazzy,’ did his numbers same way every time (during a 6-hour dress rehearsal).” 2

I would suggest that, on this occasion, Murphy was playing it straight for the sake of the continuity of a rehearsal, which is about getting things down and together that performers deem necessary, before they take the risks of performance for an audience.

For my money, Mark Murphy was more courageously improvisational than most jazz instrumentalists I’ve heard in a lifetime of listening and 35 years as a professional jazz journalist. Instrumentalists — in the protective perceptual bubble of pure music’s relative abstraction — are comparatively free of a singer’s risk of an audience rejecting a daring interpretation of a lyric and melody, especially familiar ones.

I only saw Murphy perform live once, but unforgettably in 1997, at a side stage of the Chicago Jazz Festival with Kurt Elling and his trio in, I believe, the two singers’ first ever performance together. I suspect Murphy’s appearance came at the behest of Elling, the popular Grammy-winning Chicago singer who’s primary vocal influence is Murphy. The simpatico artistic and emotional bond between the two singers was astonishing, at times dazzling, and moving. 3

As I hope the photos of that gig here show, Mark and Kurt (who’s married and straight) spent much of the set physically close to each other, glowing in mutual warmth, creativity and joy. Yet amid all their electric energy, Murphy wore a black Miles Davis T-shirt, and he embodied a sort of Prince of Darkness reincarnated, replete with world-weary eloquence and forsaken romanticism.

Internationally acclaimed jazz singer Kurt Elling (in blue shirt, both photos) shared a remarkably simpatico experience onstage with Mark Murphy, his greatest influence, at the 1997 Chicago Jazz Fest.

Listen to Murphy’s live 1999 Vienna performance on the album Bop for Miles, which is often outrageous in its improv derring-do. Yet he sustains a superb voice and technical mastery of it, to make virtually all of this performance work beautifully. As the album’s annotator Bill Milkowski writes, on the evidence of this live performance, Murphy is “a grand high exalted mystic ruler of improvisation,” a gilded designation few instrumentalists get. I couldn’t agree more with Milkowski.

Yes, I’ve heard Murphy with a mouthful of ham, and stumble in a few of his madcap scat sorties. But I think a good jazz singer ought to be guilty of both of those things at times, or he is probably not pushing the improvisational edge, with all the risk and significance that act might convey, not doing what we value him or her for doing. And the trademark grain in his low-to-mid range would gently plead, even as it understood loss and felt suffering.

(Here Murphy sings the modern standard “Speak Low” in 1992. Notice his elastic sense of time, how he fully re-imagines the song, yet even his scatting is deep in the rhythmic pocket:)

An apparently straight jazz singer Gregory Porter helps illustrate these virtues by way of his own extending of Murphy’s legacy through Kurt Elling. “He opened some doors for me which I’m thankful for,” Porter said of Elling. “When I first started, I didn’t know of Kurt other than he was on the scene. When I first started singing, I’d sing: ‘Skylark, do you have anything to say to me?’ And the way I was saying it wasn’t how it was originally recorded. I wanted to feel it, so I put the soul and gospel influence into my jazz. People would tell me, “you can’t sing it like that.” But that’s the way Kurt sings. I’d hear him insert a soulful expression into a standard. And now he’s made it acceptable.” 4

And that’s the way Mark sang, as well, on his own terms, always, his own man. His ultimate roots were less Sinatra than Louis Armstrong in “Heebie Jeebies,” the first scat improv.

Elling has also pointed out the literary contributions that Murphy made as a beat era-bred artist, sometimes setting poetry to music. The Murphy albums Bop for Kerouac and Kerouac Then and Now provide eloquent music musical testament to a great American writer who also remains undervalued, perhaps because of the seemingly haphazard way Kerouac wrote and lived out his most famous book, On the Road. Murphy also wrote and recorded resonant lyrics to a number of jazz instrumentals, notably Oliver Nelson’s “Stolen Moments” and Freddie Hubbard’s “(On the) Red Clay.” *

Among the better brief appreciations is from All Music Guide’s Murphy biographer John Bush:

“Mark Murphy often seemed to be the only true jazz singer of his generation. A young, hip post-bop vocalist, Murphy spent most of his career sticking to the standards — and often presented radically reworked versions of those standards while many submitted to the lure of the lounge singer — during the artistically fallow period of the 1970s and ’80s. Marketed as a teen idol by Capitol during the mid-’50s, Murphy deserted the stolid world of commercial pop for a series of exciting dates on independent labels that featured the singer investigating his wide interests: Jack Kerouac, Brazilian music, songbook recordings, vocalese, and hard bop, among others. 5 (And blues fans, check out this early Murphy recording of blues: songs: http://www.allmusic.com/album/thats-how-i-love-the-blues%21-mw0000203977 – KL)

The All Music Guide maintains a consistently updated website. Still, the coverage is somewhat frustrating because All Music lists no albums that are out of print, many of which collectors covet and hold artistic value.

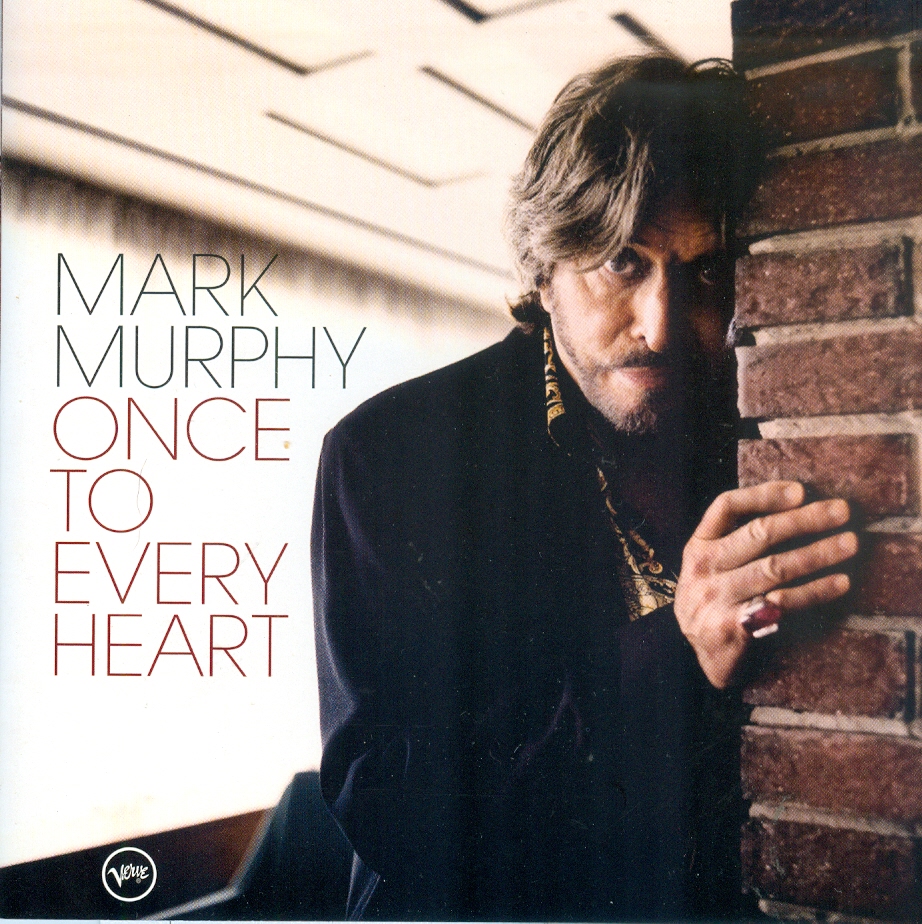

This startlingly candid photo of Murphy, for the cover of a 2005 album, reveals the weight of the challenges he endured as an “out” gay artist long before that stance was as accepted as it is today. Courtesy Verve Records.

A comment Murphy made several decades ago about jazz seems to sum up his own life and career: He compared the art of jazz to chess and basketball, recounts Down Beat magazine’s Michael Bourne: “You can imagine all the moves ahead ‘but it all changes, completely, bar bar to bar to bar. It’s really like dribbling in rhythm on a basketball court’ you can head for the baskets, ‘but other players bump you, knock you around.'” 6

I’ll let Kurt Elling have the penultimate word. I interviewed him in 2007 and posed this question: You’re taking some daring leaps with the jazz singing tradition that extends through Eddie Jefferson, Jon Hendricks, Joe Williams and Mark Murphy. What do you value most in that vocal tradition? 7

“It’s tough to single out a thing,” Elling said. “The sound of it. The intelligence of it. The hip factor. The spirit of it. And also the camaraderie of it. I feel like those are my guys. I never met Joe, but I would hope that when we meet in heaven or something, they’ll say, “Right on, kid.” I do get that from Mark and Jon Hendricks. It makes me feel I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing.

“All jazz people take their music very personally. We’re protective of the music because the world continues to not pay much attention to it. It’s something really profound and has so much to give, so I’m more hopeful than anything else.”

The profundity, spirit and hipness of Mark Murphy remain, and offer hope that his day in the sun will come.

____________

- This late-career performance of “(On the) Red Clay” by an obviously unhealthy 80-year-old Mark Murphy — with some gutsy, funky and delightful scat singing — shows Murphy’s courage and gifts, even in decline.

1 As envisioned, the memorial, when completed, would show Crazy Horse astride a horse and pointing east to the plains in a carving that would be 641 feet long and 563 feet high. Its height would be nearly twice that of the Statue of Liberty.

2 Francis Davis, Jazz and its Discontents, 2004, DaCapo, 100

3 In 2002, Elling produced the vocal summit “Four Brothers” at Chicago’s Park West Theater, which featured Elling, Mark Murphy, Kevin Mahogany, and Jon Hendricks. A cross-generational tribute to the art of singing jazz, “Four Brothers” toured Europe and the U.S. in 2003-04 to much acclaim. A final blowout performance in the summer of 2005 occurred in Chicago’s Millennium Park—a concert which featured Sheila Jordan in the fourth spot and was aptly named “Three Brotha’s and a Motha.’”

4 Down Beat magazine, Gregory Porter Blindfold Test, by Dan Oulette, Nov., 2014, p. 106

5 http://www.allmusic.com/artist/mark-murphy-mn0000244552/biography

6 Down Beat magazine, January 2016, p. 8 http://www.downbeat.com/default.asp?sect=news&subsect=news_detail&nid=2883

7 Kurt Elling interview, Kevin Lynch, The Capital Times, January 19, 2007 http://kurtelling.com/news/press_article_418.php

SIDEBAR: The written silence on Mark Murphy echoes through most book-length critical jazz anthologies and histories.

I did an informal survey and determined that there are no indexed references to this important and influential jazz singer in the following books, all published during the prime arc of Mark Murphy’s career from the mid-1950s to the present (with each book’s amount of pages after the title). Among anthologies of highly respected jazz journalists are Gary Giddins‘ two large volumes of seemingly definitive Visions of Jazz: The First Century (690 pages), and Weatherbird: Jazz at the Dawn of its Second Century (632). Giddins is also the author of a biography of Bing Crosby. Nor is there any mention in celebrated critic Whitney Balliett’s anthology Collected Works of Jazz 1954-2000 (873), largely from The New Yorker.

Among relatively recent and notable formal histories of jazz, there is nothing on Murphy in James Lincoln Collier’s The Making of Jazz: A Comprehensive History (543). More surprisingly, Murphy appears unacknowledged in both the massive and arguably definitive A New History of Jazz by Alan Shipton (965) and in perhaps the best and certainly most concise history, Ted Gioia’s A History of Jazz (444), the Second Edition of which was published in 2011. Murphy also gets no mention in Henry Pleasants’ eclectic 1974 The Great American Popular Singers: Their Lives, Careers & Art (384.)

By my arithmetic, the aforementioned titles add up to, in effect, Murphy singing his hip heart out while wandering through a 4,530-page desert of critical neglect.

Murphy fares somewhat better in the leading jazz recording guides although Jazz: The Rough Guide to Essential Recordings’ The 1995 edition includes a listing of only one album, 1991’s What a Way to Go and British critic (and Charles Mingus biographer) Brian Priestly comments, “Stylistically very consistent, he frequently uses jazz associated material for his own melodic improvisation scat singing and sounds infallibly ‘hip.'” Also British is the even more authoritative and comprehensive The Penguin Guide to Jazz. The Ninth Edition includes 13 Murphy titles including seven 3 1/2 star reviews on a four-star scale.

Interestingly the guide, written by British critics, provides some of the best and most insightful summations of the American’s career, suggesting the proverbial prophet without honor in his own land. — KL

Therese articles were originally published on Culture Currents (Vernaculars Speak) at www.kevernacular.com.