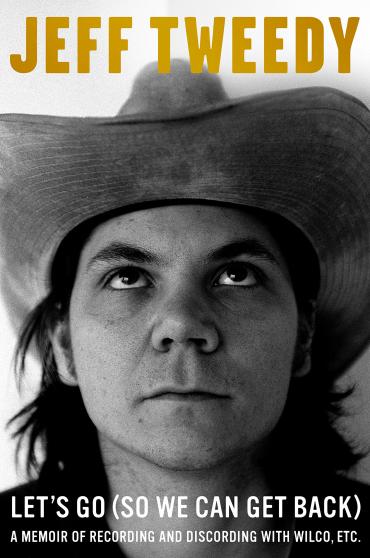

This fall, one music memoir stands above the gelatinous glut of words that have oozed onto bookshelves and into our lives. Jeff Tweedy’s Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back): A Memoir of Recording and Discording with Wilco, Etc. — the main title is a phrase his father used whenever the family headed out on a trip — sparkles like a jewel in the sludge. Tweedy is a raconteur, and his disarming presence, his nonchalance (he’s going to tell these stories, and if you want to come along for the ride, that’s fine; if not, that’s your choice), his ability to draw us in with his wink-and-a-nod humor, and his way with a story invite us into his world and keep us listening as he reveals the insights he wants to share about his life, his family, and his music.

Growing up in Belleville, Illinois, 30 minutes east of St. Louis, Tweedy learned about music in a variety of ways. Before he got his own stereo, he listened his parents’ records. His father, Tweedy writes, “had a monogamous relationship with music; he consumed one song at a time.” His sister, Debbie, and his Aunt Gail gave Tweedy a crate of 45s that the two of them had collected as teenagers. Among the records are singles by The Beatles, Herman’s Hermits, The Monkees, Sonny and Cher, and “lots of Motown stuff.” Tweedy’s favorite was The Byrds’ “Turn! Turn! Turn!”: “I felt genuine love for that song. Maybe my first feelings of love toward a piece of music. It seemed to exist in its own sonic universe, unlike anything I’d heard before. It was one of the first times I thought about the shape of a song … it felt like it followed its own set of rules … most of the other pop songs in my inherited collection had an easily identifiable verse/chorus structure, but this was different.” When Tweedy was eight or nine, his brother Steve gave him all his albums, ranging from Harry Chapin to Frank Zappa to Kraftwerk to Amon Düül to Aphrodite Child’s 666 (The Apocalypse of John, 13/18), which Tweedy says terrified him.

Of course, Tweedy tells a few stories about the origins, ascent, and decline of Uncle Tupelo and Wilco, about his work with Mavis Staples, and about his musical collaborations with his son Spencer. He includes a six-page graphic story that illustrates how he and his wife Susie met, and he includes interviews with her and Spencer in which he asks each of them what he should include about them. He’s also forthcoming about his addiction. In the introduction, he offers a disclaimer — “there will be no mention of prescription painkillers” — that he humorously recants almost immediately (“that last part was a joke”) that illustrates his genuine insecurity about talking about himself and wondering who’s really gonna read this book as well as his Samuel Beckett-like determination: “I’ll go on; I can’t go on; I’ll go on.” There’s, of course, some ink spilled on Uncle Tupelo’s album No Depression and the origins of the music that became known as alt-country (and even a passing reference, just a mention, to the magazine of that title).

As interesting as all those moments are, the most memorable moments of the book are those where Tweedy writes about songwriting. “I became a songwriter,” he says early in the book, “not when I composed that perfect couplet, or when I experienced the right amount of pain. It’s when I realized that whatever I wrote, even if it meant gutting myself in front of strangers, letting all those raw emotions come flooding out, making a fool of myself with my own words, was exactly what I always wanted to do with my life.”

Later, he reflects on aspects of his songwriting process: “Here’s what I still think about then I’m writing songs. I think about when I moved to Chicago twenty-five years ago and I was using this crappy RadioShack cassette recorder that didn’t work all that well. It was just something to get ideas down on tape so they wouldn’t disappear … Susie would get cassettes from bands who wanted to play Lounge Ax, and the ones that didn’t pass muster I would confiscate and record over with my own songs. (I’m sure most of them were perfectly fine bands, and they made songs they cared about a lot. It wasn’t personal. I promise it won’t happen again!) I’d fill up an entire tape with new material, coming up with a new tune every night as my set goal. I’d sit in our apartment with my guitar … and I’d listen to everything on the tape, whatever I’d recorded the previous nights, everything up to the blank space on the tape. Then I would imagine, ‘What comes next? What does the next song sound like on this album I’m making up as I go? If I was a teenager again, listening to an album in my bedroom, what would I want to hear next?’ There’s so much power in that silence, just imagining what could happen but hasn’t happened yet.”

Tweedy reflects on what books mean to him and his writing: “I’ve carried around a lot of books over the years that I’ve never bothered to read. I’m not that with all books. Just the books that I’m waiting for, anticipating some turning point when I’ll be ready for what’s inside. Other books I don’t feel are necessarily to be read. Sometimes, I think it can be just as inspiring to imagine what a book is about … I don’t need to read them from start to finish. My relationship with them is mostly my imagination of their potential … Books are my companions. I love books and I’m always in the middle of several at a time … Bits and pieces from Henry Miller have made their way into my lyrics, especially while I was working on Yankee Hotel Foxtrot … It’s amazing how many things I’ve been singing for years that I’ll find highlighted when I revisit the warped City Lights paperbacks I traveled with circa Summerteeth … A lot of my lyrics originate this way. You could take, say, all the verbs from an Emily Dickinson poem and set them side by side with all the nouns from ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’ and see what happens … it’s amazing how hard it is to put words next to each other without meaning being generated.”

Tweedy includes lyrics to songs from his new album, WARM, that was released just after his memoir was published (ND review). “The songs that have grown out of writing this book,” says Tweedy, “are different because I’ve been thinking about what exactly what I would like to say directly to someone. What I would like to say to you.”

Tweedy succeeds in his memoir because he is talking directly to us, honestly, humorously, directly, plainly about where he’s been and where he is right now. In many ways, this is a memoir for Tweedy (or Uncle Tupelo or Wilco) fans, but Tweedy capably draws in a larger audience because he focuses on the reasons that people listen to music in the first place: because they love music so much they find themselves in it and it expresses meaning about their world they’d never seen for themselves. Because Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back) focuses on the music and the people who make it, this may be the best music memoir of the year.

* * *

Jeff Tweedy spoke to No Depression about the role of technology in the making of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot for our Fall-Winter 2018 edition. Order your copy of that issue here!