Jim Crow and black music: from cheerful stable boy to despised symbol of institutionalized racism

Do you have a spare minute for me, yes? I would like to tell you briefly the tragic story of a poor black stableboy whohappily jumped through life but ended up, against his own will, to be an icon of structural and institutionalized racism, up until today.

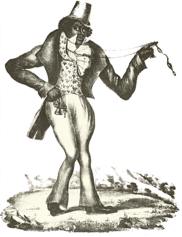

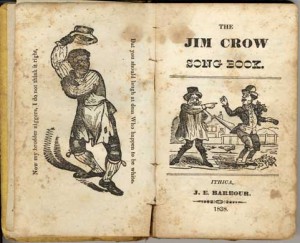

Once upon a time in America, around 1828, a second rang, white actor from the New York theater scene one day noticed during a tour in a Southern river town a black stableboy, named Jim Crow, dressed in ragged cloths. The boy performed a song and dance called ‘Jumping Jim Crow’ and the lyrics went as follows:

”Weel about and turn about and do jis so,

Eb’ry time I weel about I jump Jim Crow.”

The actor was fascinated with the scene of this stableboy dancing happily around and immediately realized the enormous show potential of what he witnessed for entertaining his own public. In modern terms, we would say that he was convinced that there was a product to be succesfully marketed. To the boy’s great astonishment, he bought his outfit and learned meticilously his dance and song. The boy himself didn’t grasp very well what was happening; after all: as most of his black friends he was nothing more than a piece of property. Dancing and singing was for him only the natural way of expressing himself and making his life bearable in the face of the daily hardships. Who was he, Jim Crow, to know that he had just inspired a man who would use his format and character to kick off the first popular, national musical industry in America.

Though not a star actor, the white man had a nose for show business and took the act to the stage. He felt that with the growing urbanisation, especially in the north of America where he enjoyed his main audience, there was an insatiable appetite for entertainment. The cities grew like mushrooms and the urban working class was hungry for light entertainment to brighten up the evenings and weekends. The white man put cork on his face to look like Jim Crow and started imitating the dance and song that the stableboy had showed him. It was not a new thing, a white actor painting his face black: already centuries before actors on the English theater stage had done it before him. The real genius of the New York white actor was the exact timing of combining in a lighthearted way the black face painting with African inspired music, bringing it to an audience that wanted to meet this ‘other’ culture in their country. As black artists were not allowed on stage, it seemed the only way for the white public to get acquainted with this exotic part of their nation that came from Africa and the West Indies. The theatrical context made it all the more attractive since it allowed to keep a safe distance between their own lifes and the strange culture that was showcased to them in a most amusing way. The characters who performed the dancing and singing in an African inspired way were a brilliant combination of puppets on a string, showing at the same time human traits, making it all the more realistic. It was called the black face minstrel show.

Should the stableboy have seen what showbusiness had done to his song and dance, he would probably not have been very happy and would have stopped singing and dancing. His ‘jumping’ and singing was completely ripped of his context and meaning and was deformed into a caricature; he would have seen stage actors who depicted him as a naive, clumsy, slow-thinking and slow-moving country darkey who wore tatters, rags and a battered hat. If he wasn’t singing and dancing on the levee, he was sleeping, fishing, or hunting possums. The white also presented him as being hooked on watermelons and as non-reluctant to steal the chickens from his ‘massa’.

Whatever. The white audience, males predominantly, cried it out of laughter and couldn’t get enough of it. The show skyrocketed: new black face minstrel groups were springing out of the ground in Northern Cities as it was the most natural thing. The minstrelsy, at first just an ‘entr’act’ in other theater performances was becoming a fully fledged show in its own right, and even theaters were being built for it.

I don’t know how Jim would have reacted if he had known that, as the success grew stronger and stronger, his character received the company of many stereotyped-friends: Mammy, the wise woman, Uncle Tom, the good, gentle, religious and sober man, Buck, the big proud black, sometimes menacing but always interested in white women, and Jezebel, the temptress. Not to forget the adorable Pickaninnies with their bulging eyes, unkempt hair, red lips and wide mouths into which they stuffed huge slices of watermelon. It all seemed one big happy family, enjoying the life of slavery under the patronizing guidance and caring hand of the white master and mistress of the plantation. Life couldn’t be better, and that was a very comforting thought for the urbans of the north. If you think of it: minstrelsy had it all! Not only did Americans, for the first time in their history had their very own music – different from what their European ancestors had -, this music convinced them that as white Americans they were a superior human species, so much wiser and better than the lazy, dum nogoods coming from Africa.

But our New York actor that ignited the minstrelsy fire had luck on his side when he launched his new act – a new act, that was by the way gradually ornated with banjo, bones, tambourine and fiddle. He was not alone to be credited for the succes. The political climate of the day was extremely receptive to the show. I even dare to put it stronger: I say that blackface minstrelsy was sort of an inevitable cultural cement in the social and political building of the time period. The import of new slaves from abroad had been forbidden for a few decades and the white men observed more and more upheavals from the discontented slave population. On the European continent the industrialisation was progressing at a quick pace thanks to – among other things – the free movement of the labour force. In America, capital was at first mostly invested in the agricultural business of the South and there was a need for fostering industrialisation to compete with the economies from the other side of the Atlantic ocean. Was slavery not an obstacle to that competition? More and more, the conviction grew – also from a humanitarian perspective – that slavery was an institution that was outdated and could not be maintained in the long run. But what to do with the black that would be freed? How to deal with them, economically, socially and politically? Nobody had a clear answer to that and fear of what might happen to the ‘acquis’ of the white was just around the corner. The white saw that black clouds accumulated on the horizon but they had no idea how to deal with it and where to seek shelter from the coming bad wheather. They realised that shelters would be needed; the only question was: how soon would the rain start and how much would fall. And another even more poignant question was left unanswered: what to do with the uppity blacks?

Black face minstrelsy was comforting the white for the time being, making them feel at ease: the African Amercians were not a real threat to them and their society since they were after all not humans to the same degree as the white. Each minstrelsy performance made it abundantly clear that blacks were not able to look after themselves and that the future would remain in the hands of the white. It legitimized in a most reassuring and at the same time amusing way that blacks would remain at the back row of society, occupying only the space that the white was prepared to reserve for them.

The contemporary political ideas were in a strange but not accidental way perfectly in line with the message that the white actors, painted in black face, spread through the ridiculed imitation of what they believed the American African represented socially and culturally. Mr Andrew Jackson, the seventh president of America, personified as no other the ambition of the common man to built a nation that was rooted in the virtues of the zealous and adventurous white citizen. For the first time in the history of America, a president appealed to the votes of all these “common” men of the nation, as long as they were white of course. He built out a political party machinery that transcended the local context and he professionalized policy making in an irreversable way. Also, it was the mission of this political class, under the strong leadership of the President’s executive power, to move the frontiers to the west. It was a pity if this expansian came at the cost of the native Americans who were asked, with a firm hand, to make room for the economic industrious white who needed land to still their hunger.

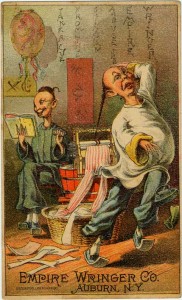

Jim Crow would have never guessed that the pastiche of his jumping and singing would in a matter of only a few years serve as an ideological addendum to a political program of a party which labeled itself as ‘Democratic’ and that aimed at establishing a strong nation that was underpinned by the white common man, at the expense of all non-whites. It would perhaps have comforted him slightly to know that not only he and his black friends were the victim of this policy, but that also other non-whites as the native Americans and the immigrants coming from the Asian countries were targetted. Perfectly following the presidential ideas that promoted the pushing of the American frontiers to the West, the minstrelsy surfed along on the waves of this geographical expansion to find an audience in the new western counties. From the Atlantic to the coastal areas at the North Pacific, minstrelsy entertained the public. Just as the stereotyped African American amused the public in the east, the Chinese stereotyping didn’t leave any doubt as to the potential role that an Asian would ever be allowed to play in American society. The more the ‘yellow face’ was seen as a potential threat for the white labour force, the bigger the family of Asian stereotypes became: Coolie, the low rang worker, the Yellow Peril, the alien, the Deviant, the laundryman, operator of opium dens and importer of prostitutes, the Dragon Lady or Lotus Blossom, the agressive or sexual opportunistic woman, or the Gook: the invisible man with a superhuman endurance and ability to absorb punishment. Yellow on the West Coast, Black on the East Coast.

Minstrelsy showed its capacity of improvisation also in its thematic flexibility and adaptability, characteristics which undoubtedly contributed to its persistent succes.

After having navigated with many a compromise act between the painful thorns of the slavery issue and its extension in the north-south political struggle, the Emancipation Declaration of 1863 and the settlement of the Civil War in 1865 laid the cards open on the table, at least for the moment. Jim would have jumped and sung stronger and more joyful than ever before. Blacks were freed and were even promised some land that they were allowed to call their own. Moreover, they would even receive the mules to help them in growing their very own crops (let us not be too sarcastic and forget for a moment that the whites, once the war was over, didn’t need the mules any longer anyhow, so the ‘gift’ was not really a gift). For the first time since Jim’s fellow African friends came ashore in the early 17th century, spring was in the air. As part of a large programme, called ‘Reconstruction’, that was to assist the south to recover from the devastating effects on all levels of the Civil War, the African Americans were not only promised a certain degree of economic independency, they would also be granted political rights.

The feast was extended to the entertainment sector where Jim Crow had been able to seduce the audience. As freedmen, the African Americans could enter as actors through the doors of the theater stage. However, the effects of more than two centuries of white supremacy were not wiped out by a simple Declaration or by the political willingness and humanitarism of some groups. The black face theater had proven its winning and lucrative potential for over two decades and the expectancies of the public were not changed overnight. Jim Crow’s character and his friends remained a popular act, and for the African Americans there was no immediate and realistic alternative for participating in (the white controlled) show business than to learn how to imitate the white who imitated them. So, blacks blackened their skin with cork, dressed in ragged clothes, put on large worn out shoes and grabbed the battered hat to join white black faced actors in praising the good old plantation life. Next to offering them an acces to cash, adapting to the black face minstrelsy was also an investment in the future for the African American. The show business had become big business that was more and more managed according to professional standards. If putting on black cork to confirm the existing, racial stereotypes was the price to pay for the acquisition of professionalism, so be it. I may even add that a professional black actor who managed to enter completely the role of the imitating black faced white actor succeeded in creating an intimate relation of conspiracy with the black audience – which became gradually more and more important – conveying messages beyond comprehension of the white pubic. And let us finally not forget, when trying to comprehend the seemingly incomprehensible observation of blacks painting their face black, that by doing so, the African American did not only learn to master a professional entertainment format, he moreover gained some control of the persona on the stage. It was as if Jim Crow would again get his hands on what the theater had made of the mould of his dance and song.

What in the early years after the Civil War looked as the early spring for the African Americans all too soon proved to be only a deceptive and disappointing few days of sunny days in the winter season that would soon be back again as bitter and as cold as never before. No full decade passed since the Proclamation of Emancipation before c

After all is, Zip Coon seemed more suited to describe the dehumanizing segregation. He was not only lazy and chronically idle, inarticulate and buffoon. Though he was not happy with his status, he was too cynical to attempt to change his lowly position. He was the citified young dandy who disrespected the whites. Unlike Jim Crow who was an innocent country boy, satisfied with his position, Zip Coon was the ignorant, indolent black who was devoid of honesty or personal honor, most of the time drunken and addicted to gambling, showing off his lustful desires. Zip Coon was a mean adult; Jim Crow was a young, happy lovable boy that had come to accept his fate. Zip Coon was a figure who could easily be hated; Jim Crow was a figure who amused and was almost tender. Why then on earth did Jim Crow deserve that his name be forever associated with demeaning laws that were meant to keep intact a system that Jim Crow had never put into question?

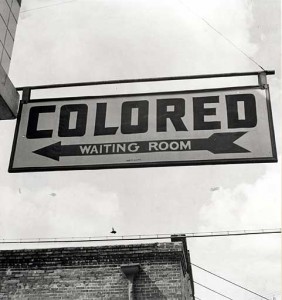

We will never know the answer. What we do know is that at the moment that Jim Crow’s name was disgracefully abused, he also lost the status of star actor on the minstrelsy stage to ….yes, Zip Coon. The latter character was much more congruent with the dominant social and political climate of racial hatred. It is no coincidence that by the end of the 1870′s the original black face minstrelsy lost its initial glamour and attraction and was slowly transforming into entertainment formulas that were more adapted to a society of which the social and economic texture was fundamentally changing in the wake of a booming industrialisation and geographical expensian. A praising of the charms of the happy plantation life was no longer responsive to what the public expected. Moreover, the black face minstrelsy had lost part of its ideological ‘raison d’être’. It was no longer expected to provide a tentative answer to a racial question; the answer had been delivered and taken form in an unambiguous way by the Jim Crow laws: blacks were equal, but only within the confined space of their own surroundings.

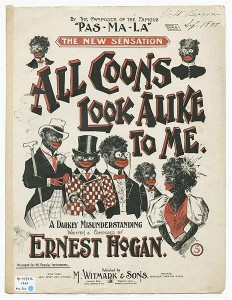

Vaudeville became the heart of the American showbusiness and variety entertainment for men and women, grouping on a common bill a diversified set of acts as dancing, comedy, magiciens, song, and …minstrels. The frequently denigrating and offensive coon song hit the top of the bill; it florished. I still wonder whether it was hatred or complete ignorance, or perhaps a cocktail of both, which were the great inspiration of the coon song writers. In any case, the coon songs became synonymous with a general disdain of the African American population. Compared to the coon song, the earlier black face minstrel performance looked innocent.

As two decades before, the African American participated in the creation and performance of a repertory that was an utterly scorn of themselves. But can they be blamed? At the end of the day, it was the heavy price the black had to pay once more to gain entrance to the popular music business. The professional experience that was acquired during the black face minstrelsy hey days was being put to value. And the later musical development would bear the fruits of this ‘sacrifice’.

The coon song itself was not brilliant and original from a lyrical and thematic perspective, but the music was. It was brought with a syncopated rhythm that was very exciting and that found a lucrative market, and this market was bigger than ever before. There was not only the theater where the audience could enjoy the songs, the business of the publication of sheet music gained momentum. Music sheets were being sold in millions of copies. Where at first the African Americans could deploy their talent only on stage, from the late 19th century their talent also blossomed as song writers, even if their product was at the end of the day marketed by the white. As long as they responded to the expectancy of the white audience that saw all coons alike as the same bunch of nogoods, the African Americans even made name and fame on the wax cylinders of the brand new record business that was looking to define itself after Edison’s invention.

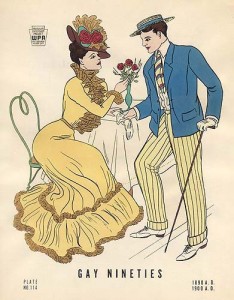

The attention that we have paid to the ‘roaring twenties’ has cast a shadow on the importance of the ‘gay nineties’ which were a decade that witnessed the birth of the modern culture. The American society was forever changing its face in the last decades of the 19th century. The economy boomed and technological progress filtrated every day life. The automobile, the recording and wireless transmission of voices and music were only some of the symbols of this revolution that was taken place. The expansion to the west in America was made possible by an exponential growth of the railroad sector, and banks were all too keen on financing this westbound exploitation of farm land. Business tycoons made huge profits. The catastropic burst of the bubble in 1893 leading to an economic and financial crisis that would last for more than five years and would be equalled only by the crash of 1929 was only a temporary stop to the modernising of America and for that matter of the whole western world.

Also culturally the last decades of the 19th century were boiling and bubbling over with life. The recording technology was in itself an important creative incentive for music. Next to the coon song, the vaudeville and the marching band were enormously popular. America even got his own ‘March King’. Making use of the ever expanding rail road network, travelling medicine shows integrating minstrelsy acts and probably also the first blues performances reached out to the rural audience that couldn’t make the trip to the urban theaters. New musical styles were being tested and developed. Change was permanently in the air.

Sadly, Jim Crow’s only a

For a naive outsider it looked as if the music business was democratized. All material forms of song distribution channels offered the African American the opportunity to deploy the talents that had been accumulated since the black face minstrelsy had opened its doors for the ‘real’ black. Even the big music houses sold black sheet music to both the black and white Americans. “All coons like alike to me”, written by an African American was a million seller. The “Whistling Coon” and “The laughing song” required the black performer to wax it a few thousand times to meet with the market demands and made it the first best selling recordings in America. This outside racial democratization of the music business was hiding the fact that whites continued to define the parameters wherein African inspired music could be marketed; they stayed the ‘master’ of the black, controlling his basic social position.

Yet, we can never underestimate the gigantic role that has been played by those numerous anonymous black pioneers in the Americanisation process of the music industry, and at the end of the day, leaving an indelible print on modern music. The character of Zip Coon may have had a relative short career in the theater because soon its syncopation and polyrhythms mingled with the popular jigs and march band music to give lead to the rag time craze and in its wake to jazz music, the coon music had meanwhile helped to sh

It all had started with the second rang actor from New York meeting a stable boy, jumping and dancing. Honesty obliges me to tell you that nobody is really sure if indeed this meeting has taken place. It might well have been that the actor with his antenna for novelty has attentfully observed a wide range of African inspired songs and dances and has distilled a stage character from it. Whatever, Jim Crow remains for me the symbol of both the irreplacable role that African Americans have played in making the modern music what it is today. Unfortunately, history has Jim Crow’s name also burdened with the bitter taste of racial segregation. Legally, the Jim Crow laws may have been buried in the 1960′s, their de facto legacy still lives further today in everyday life and the spirit and actions of many. He hasn’t disappeared from the musical scene either and has learned to adapt to the modern media of YouTube and MP3. How else can we explain the mega million success that was scored last year in August when a bunch of American white youngsters transformed the news broadcast of a young black narrating most tragically the attempted rape of his sister? The racial structures that were at work in the beginning of the 19th century and which lead to the popularity of the black face minstrelsy and coon songs have all but lost their vitality and inspirational powers.

_____________________________________________________

SOURCES

___________________________________________________________

– http://www.bgsu.edu/departments/acs/1890s/ragmusic/music.html

– http://kclibrary.lonestar.edu/19thcentury1890.htm

– https://pantherfile.uwm.edu/jnelsen/www/ushist/contents.html

– http://www.academicamerican.com/progressive/topics/progressive.html

– http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?HHID=340

– http://www.columbia.edu/cu/cjas/salem2.html

– http://parlorsongs.com/insearch/coonsongs/coonsongs.php

– http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?HHID=633

– http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/foster/peopleevents/p_christy.html

– http://ourblues.wordpress.com/2011/11/22/constructing-tin-pan-alley-from-minstrelsy-to-mass-culture/

– http://ourblues.wordpress.com/2011/11/17/minstrelsy-and-the-construction-of-race-in-america/

– http://ourblues.wordpress.com/2011/10/18/early-minstrel-show-music-1843-1852/

– Alexander Saxton: Blackface Minstrelsy and Jacksonian Ideology, 1975

(xroads.virginia.edu/~DRBR2/saxton.pdf)